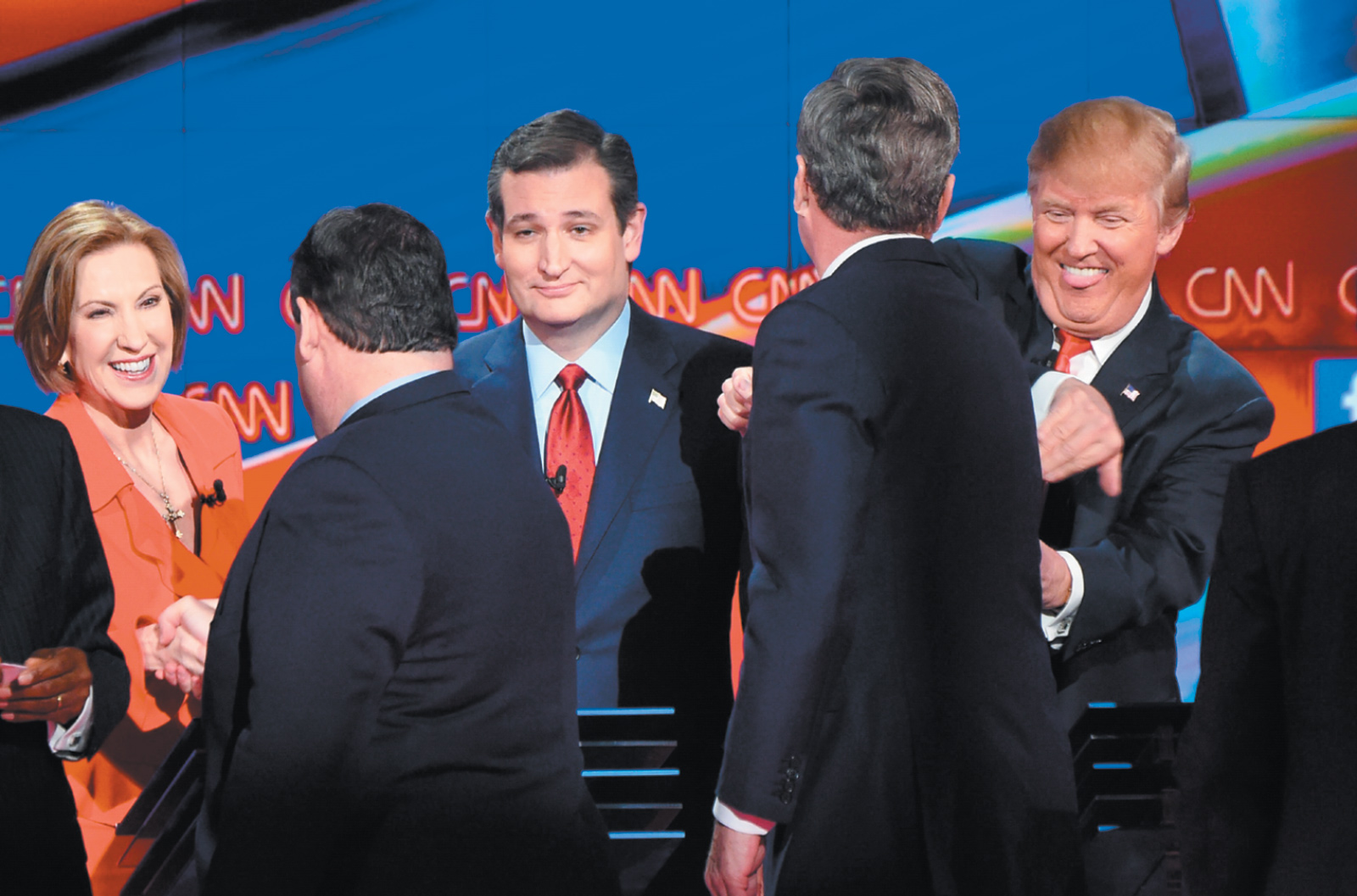

Everybody told everybody early in this year’s presidential campaign (during what was called Trump Summer) that we had never seen anything so sinisterly or hilariously (take your choice) new. But Trump Summer was supposed to mellow into Sane Autumn, and it failed to—and early winter was no saner. People paid to worry in public tumbled over one another in asking what had gone wrong with our politics. Even the chairman of the Republican National Committee, Reince Priebus, joined the worriers. After Mitt Romney lost in 2012, he set up what he called the Growth and Opportunity Project, to reach those who had not voted Republican—young people, women, Latinos, and African-Americans. But its report, once filed, had no effect on the crowded Republican field of candidates in the 2016 race, who followed Donald Trump’s early lead as he treated women and immigrants as equal-opportunity objects of scorn. Now the public worriers were yearning for the “good old days” when there were such things as moderate Republicans. What happened to them?

The current Republican extremism has been attributed to the rise of Tea Party members or sympathizers. Deadlock in Congress is blamed on Republicans’ fear of being “primaryed” unless they move ever more rightward. Endless and feckless votes to repeal Obamacare were motivated less by any hope of ending the program than by a desire to be on record as opposing it, again and again, to avoid the dreaded label RINO (Republican in Name Only).

E.J. Dionne knows that Republican intransigence was not born yesterday, and he has the credentials for saying it because this dependably intelligent liberal tells us, in his new book, that he began as a young Goldwaterite—like Hillary Clinton (or like me). He knows that his abandoned faith sounded themes that have perdured right down to our day. In the 1950s there were many outlets for right-wing discontent—including H.L. Hunt’s Lifeline, Human Events, The Dan Smoot Report, the Fulton Lewis radio show, Willis Carto’s Liberty Lobby, the Manion Forum. In 1955, William F. Buckley founded National Review to give some order and literary polish to this cacophonous jumble. But his magazine had a small audience at the outset. Its basic message would reach a far wider audience through a widely popular book, The Conscience of a Conservative, ghostwritten for Barry Goldwater by Buckley’s brother-in-law (and his coauthor for McCarthy and His Enemies), L. Brent Bozell.

The idea for the book came from Clarence Manion, the former dean of Notre Dame Law School. He persuaded Goldwater to have Bozell, who had been his speechwriter, put his thoughts together in book form. Then Manion organized his own and other right-wing media to promote and give away thousands of copies of the book. Bozell did his part too—he went to a board meeting of the John Birch Society and persuaded Fred Koch (father of Charles and David Koch) to buy 2,500 copies of Conscience for distribution. The book put Goldwater on the cover of Time three years before he ran for president. A Draft Goldwater Committee was already in existence then (led by William Rusher of National Review, F. Clifton White, and John Ashbrook). Patrick Buchanan spoke for many conservatives when he called The Conscience of a Conservative their “New Testament.”

The Goldwater book, Dionne says, had all the basic elements of the Tea Party movement, fully articulated fifty years before the Koch brothers funded the Tea Party through their organizations Americans for Prosperity and Freedomworks. The book painted government as the enemy of liberty. Goldwater called for the elimination of Social Security, federal aid to schools, federal welfare and farm programs, and the union shop. He claimed that the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board decision was unconstitutional, so not the “law of the land.” He said we must bypass and defund the UN and improve tactical nuclear weapons for frequent use.1

It was widely thought, when the book appeared, that its extreme positions would disqualify Goldwater for the presidency, or even for nomination to that office. Yet in 1964 he became the Republican nominee, and though he lost badly, he wrenched from the Democrats their reliably Solid South, giving Nixon a basis for the Southern Strategy that he rode into the White House in the very next election. The Southern Strategy had been elaborated during Nixon’s campaign by Kevin Phillips, a lawyer in John Mitchell’s firm. The plan did not rely merely on Southern racism, but on a deep conviction that, as Phillips put it in a 1968 interview, all politics comes down to “who hates who.”2 In that interview, Phillips laid out an elaborate taxonomy of hostilities to be orchestrated by Republicans—another predictor of the Tea Party. Dionne argues, with ample illustration decade by decade, that this right-wing populism would remain a Republican orthodoxy, latent or salient, throughout the time he covers.

Advertisement

Joe Scarborough, in a recent book, The Right Path: From Ike to Reagan, How Republicans Once Mastered Politics—and Can Again, claims that moderate conservatism is the real Republican orthodoxy, interrupted at times by “extremists” like Goldwater or the Tea Party.3 He suggests Dwight Eisenhower as the best model for Republicans to imitate. Yet Scarborough is also an admirer of Buckley, and his thesis does not explain—as Dionne’s thesis does—why Buckley despised Eisenhower. Eisenhower, as the first Republican elected president after the New Deal era of Roosevelt and Truman, was obliged in Buckley’s eyes to dismantle the New Deal programs, or at least to begin the dismantling. Buckley resembled the people today who think the first task of a Republican president succeeding Obama will be to repeal or take apart the Affordable Care Act.

Eisenhower, instead, adhered to the “Modern Republicanism” expounded by the law professor Arthur Larson, which accepted the New Deal as a part of American life. Eisenhower said, “Should any political party attempt to abolish social security, unemployment insurance, and eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear of that party again in our political history.” It was to oppose that form of Republicanism that Buckley founded National Review in 1955, with a program statement that declared: “Middle-of-the-Road, qua Middle-of-the-Road is politically, intellectually, and morally repugnant.”

Buckley hated Eisenhower’s foreign policy as much as his domestic one. He said, “Eisenhower was above all a man unguided and hence unhampered by principle. Eisenhower undermines the Western resolution to stand up and defend what is ours.” When Russia put down the 1956 uprising in Hungary and Eisenhower did not intervene, National Review called for people to sign the Hungary Pledge—to have no dealings with iron curtain products or exchanges (Buckley’s wife had to give up Russian caviar).

Admittedly, Buckley did not, like Robert Welch (founder of the John Birch Society), think Eisenhower was a secret Communist (as many Republicans now think Obama is a secret Muslim). Buckley thought that Eisenhower had no greater purpose than his own success: “It has been the dominating ambition of Eisenhower’s Modern Republicanism to govern in such a fashion as to more or less please more or less everybody.”

The sense of betrayal by one’s own is a continuing theme in the Republican Party (a Fox News poll in September 2015 found that 62 percent of Republicans feel “betrayed” by their own party’s officeholders). The charges against Eisenhower were repeated against Nixon, who brought Kissingerian “détente” into his dealing with Russia and renewed diplomatic ties to China. On the domestic front, he imposed wage and price controls and sponsored the welfare schemes of Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Buckley joined the effort to “primary” Nixon in 1972 by running John Ashbrook against him. Buckley campaigned for Ashbrook in New Hampshire, but he succumbed to pleas from Spiro Agnew (before his disgrace) and Henry Kissinger (a new friend of his) that he endorse Nixon for the general election.

The story keeps repeating itself. The right opposed Gerald Ford—not for pardoning Nixon (as the left did) but for continuing Kissinger’s effort at détente (the Helsinki Accords), advancing the Panama Canal treaty, and making the hated Nelson Rockefeller his vice-president. (At the 1976 Republican convention, Ford had to humiliate Kissinger and Rockefeller in order to head off Reagan’s challenge, and made Bob Dole his running mate—all to no avail).

Both Bush presidents were denounced by the Republican right, the first for raising taxes, the second for expanding Medicare’s pharmaceutical support and expanding the government’s role in education—and the two of them for increasing the size and cost of government. Even the sainted Reagan disappointed the hard right with his arms control efforts, his raising (after cutting) taxes, his failure to shrink the government, and his selling of arms to Iran (though that bitterness has been obscured by the clouds of myth and glory surrounding Reagan).

To be on the right is to feel perpetually betrayed. At a time when the right has commanding control of radio and television talk shows, it still feels persecuted by the “mainstream media.” With all the power of the one percent in control of the nation’s wealth, the right feels its influence is being undermined by the academy, where liberals lurk to brainwash conservative parents’ children (the lament of Buckley’s very first book, God and Man at Yale). Dionne shows how the right punishes its own for “selling out” to any moderate departures from its agenda once a person gets into office.

Advertisement

A good example of this was the rejection of one of its own “Young Guns,” House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, in his 2014 bid for reelection. Dionne writes:

Cantor’s district was changed [by gerrymander] to give him more Republican voters—and he lost especially badly in the primary among the new and very conservative voters who had been moved in to strengthen him in the general election.

Even Kevin Phillips proved that he was not only a connoisseur but a practitioner of resentment against leaders when he said that Bill Buckley was selling out when he palled around with liberals on his yacht—he called him the leader of la-di-dah conservatives.4 (Who hates who now?)

Joe Scarborough claims that the Republicans have continually oscillated between moderates and extremists. But he could find only two stellar moderates in the last half-century, Eisenhower and Reagan. Some oscillation! Dionne comes closer to the facts with his tale of a ground bass of growls against moderation, swelling at times or diminishing, but continuously present and becoming more embittered. It is appropriate that this feeling has been in alliance with the Confederate South, the loser of a war it still thinks it should have won. The rest of the Republicans may not be as racist as the South, but they cannot prevail at the federal level without it. All grievances gravitate toward one another.

Some conservatives rightly say that Bill Buckley was their best advocate—he elevated their vocabulary and taste, and he shuddered away from vulgarians like Robert Welch and Willis Carto. But he knew there could not be a conservative party if the South were not included in it. In 1957 he published an editorial titled “Why the South Must Prevail.” It said:

The central question that emerges…is whether the White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas where it does not predominate numerically? The sobering answer is Yes—the White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race.

This feeling that superior people have license to circumvent democracy is still with us—when strategic gerrymandering and restrictive voting procedures freeze out minorities, the young, and the elderly, giving Republicans stronger representation in Congress than the popular vote warrants. Chief Justice John Roberts perpetuated this inequity when he voided Section Four of the 1965 Voting Rights Act—a decision followed immediately by a rush to impose new restrictions on who, where, and by what validation people can vote.

The idea that America has somehow outgrown or transcended racism is an ever-renewable delusion. Some hoped that the election of a black president would mark the end of racism. But in fact it blew on the embers of racism we have beneath us all the time. Otherwise how could Americans continue to think against all evidence that the incumbent president is not even a citizen of the country he leads? As a blanket statement, only Republicans think that. In a September 2015, Public Policy poll, only 29 percent of Republicans grant that Obama was born in the US (among Trump supporters, it is 21 percent), and 54 percent think he is a Muslim (it is 66 percent among Trump supporters).

The surge of Trump for half a year at the top of Republican polls was mystifying to many people. They thought the lead would quickly evanesce, since it was based on the man’s celebrity-cum-effrontery, not on any real political support. But the support was entirely political. Remember, Trump first became a political factor by claiming that Obama has no valid birth certificate—a charge he has never abandoned. He was mocked for that, but why should he abandon it? It turns out that a majority of Republicans have held that belief and never renounced it. Trump was giving voice to the growl of Republican orthodoxy that Dionne analyzes.

The truth is that conservatives are right to feel that their own moderates are sell-outs. To be (even moderately) a moderate is to leave the Republican Party—to be what Buckley called an immoral Middle-of-the-Roader. To accept Enlightenment values—reason, facts, science, open-mindedness, tolerance, secularity, modernity—is to lower one’s guard against evils like evolution, concern about global warming, human equality across racial and sexual and religious lines—things Republicans have opposed for years and will not let their own members sell out to. They rightly intuit that there is only one Enlightenment party in America, and the Republicans are not it. That is why they have to oppose in every underhanded way they can the influence of younger people who are open to gays, to same-sex marriage, to feminism.

This is the conclusion I come to from a reading of Dionne’s account of Republicans across the half-century story he tells. But I must admit that Dionne does not come to the same conclusion. He still has hopes that moderate forces can ride to the rescue of the party. He places those hopes in the men he calls Reformicons. He still entertains the dream of Russell Kirk that American Republicans will somehow become Yankee Edmund Burkes, as Thoreau hoped to form Yankee Buddhists. It is not surprising, then, that Dionne calls a Burke scholar, Yuval Levin, the leader of his Reformicons. Membership in this movement seems relatively easy. There is no entry test on Burkean knowledge.

Dionne comes up with a wide scatter of Reformicon members—it contains, besides Levin, Michael Needham, Mike Lee, Michael Gerson, Peter Wehner, David Frum, Michael Strain, Josh Barro. Bruce Bartlett, Ross Douthat, Reihan Salam, Charles Murray, Ramesh Ponnuru, David Brooks, Arthur Brooks, and Henry Olsen. Dionne admits that these are rather “bookish types”—there is only one office holder among them (Senator Lee of Utah). Some of these “moderates” are at least part-time Tea Partiers. Needham and Lee, for instance, cooked up the 2013 government shutdown for which Senator Ted Cruz took most of the credit or blame.5 Loose as this aggregation is, Dionne even grants John McCain a kind of honorary membership in his maverick days—before he started palling around with Sarah Palin (she may have read something, but I doubt that it was Edmund Burke).

This is not a very disciplined or cohesive cadre. Some would no doubt have trouble identifying themselves with others in the “moderate” movement for which Dionne is recruiting them. They have different institutional loyalties and no shared base for concerted “reformiconning.” Besides, Dionne shows that it is risky for Republicans even to toy with talk of moderation. That is why even “mainstream” Republican candidates steer away from support for evolution, or measures against global warming, or taxes on the rich, or same-sex marriage. None wants to be guilty of compromise or looking soft. The right hated George H.W. Bush’s plea for a “kinder and gentler” party kindling “a thousand points of light.” They had no more kind or gentle feeling about George W. Bush’s “compassionate conservatism” and his promise to “leave no child behind.” They think that is Democrat talk. And they are right.

-

1

Barry Goldwater, The Conscience of a Conservative, half-century edition edited by C.C. Goldwater, with a foreword by George Will and an afterword by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (Princeton University Press, 2007). ↩

-

2

See Garry Wills, Nixon Agonistes: The Crisis of the Self-Made Man (Houghton Mifflin, 1970), pp. 265–269. ↩

-

3

See Garry Wills, “Can He Save the GOP from Itself,” The New York Review, January 9, 2014. ↩

-

4

See John B. Judis, William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives (Simon and Schuster, 1988), p. 378. ↩

-

5

See Stephen Moore, “Michael Needham: The Strategist Behind the Shutdown,” The Wall Street Journal, October 11, 2013; and Alex Rogers, “Utah Senator Mike Lee: The Man Behind the Shutdown Curtain,” Time, October 22, 2013. ↩