Everyone who has seriously worked in politics and journalism agrees that this has been the strangest and least predictable presidential campaign we’ve ever seen. This is largely because of Donald Trump’s angry elephantine presence. Though not solely: Bernie Sanders’s fund-raising prowess and skill at campaigning have rattled all Democratic assumptions. And then comes an event like the death of Antonin Scalia, which will reverberate throughout the length of the campaign.

None of us has experienced anything quite like it. And yet with the benefit of hindsight, we can see that what is happening in this campaign, for all its crazy-sounding dogmatism, isn’t so crazy at all. The developments within both parties reflect the long-standing anxieties that liberals and conservatives feel about the country, anxieties that have only grown sharper as time has passed. For liberals, the chief concern for thirty-five years now has been about the unfairness of the economy—virtual wage stagnation for most workers, huge gains for the top 1 percent, and the lax regulatory and enforcement regimes that have permitted those outcomes, along with slow recovery from the most recent recession.

For conservatives, for about the same period of time, the main worry has been what is broadly called “culture,” by which we really mean the anger and resentment felt by older white Americans about the fact that the country is no longer “theirs” and that their former status and authority no longer seem what they once were. This rubric takes in a number of issues—immigration, especially illegal immigration; same-sex marriage; a black president in the White House; all the things that conservatives bundle under the reviled label “political correctness.” In their minds it is some sort of taint that has infected every institution in this once-great nation and is destroying it daily before their eyes.

It is no wonder, then, that a man who possesses a sharp instinct for identifying and simplistically fulminating against all these evils should have emerged to define the shape of the Republican race. Donald Trump’s rise has taught us a few things about him, chiefly his instinct for dominating the daily news; but mostly it has taught us what the central voting issue of conservatives in the Obama era really is. It’s not taxes or terrorism or even abortion rights. It is that we have been letting in too many undesirables who reject conservatives’ values, compete for jobs, and are changing the country radically and irreparably for the worse.

Trump has committed many apostasies, such as his increasingly aggressive condemnation of the Iraq War. (In the February 13 debate, he went so far as to accuse George W. Bush of intentionally lying about Iraq’s alleged weapons. This diverges sharply from the standard Republican line that it’s simply a pity that the intelligence was so wrong.) Trump’s record of statements and positions, which include past support for national health care, abortion rights, and the Clintons, would have been enough to bury most candidates. But for the base of the party he has popular views on Latino and Muslim immigrants, whom he wants respectively to deport and keep out of the country altogether. All else, up through the first three contests at least, two of which he won commandingly, can be forgiven. Or indeed admired. How many of those shocked by his coarseness were among the millions who followed his Apprentice reality show when his bullying manner was already popular?

The general thinking after his attack on President Bush was that he’d finally gone too far, but that’s been the general thinking on Trump many times. It’s always been wrong, and it was wrong again in South Carolina, which he won by eleven points. In a very pro-military state, he in essence accused an ex-president who is still reasonably popular among Republicans (77 percent approval, according to one pre-primary poll) of treason or a war crime or both—and won handsomely.

Three days later, he followed that win with a dominant victory in the Nevada caucuses, and as this is written was ahead in the polls in most of the eleven states set to vote on March 1. So unless Trump collapses somehow, or everyone eventually drops out except Florida Senator Marco Rubio, setting up a two-man race that many people believe Rubio could win, Republicans are looking at the very real possibility that Trump will be their party’s nominee. Many leading conservatives are mortified at the thought. In mid-January, just before the voting began, National Review ran a huge “Against Trump” symposium, which led with a thundering editorial:

Donald Trump is a menace to American conservatism who would take the work of generations and trample it underfoot in behalf of a populism as heedless and crude as the Donald himself.

It also featured contributions from twenty-two conservative writers and activists such as Glenn Beck, William Kristol, and David McIntosh, the president of the influential Club for Growth.1

Advertisement

A few Republican grandees, notably Bob Dole, have piped up in Trump’s defense. Sarah Palin endorsed him on January 19, in a prolix and sometimes incoherent speech that made the candidate, who was standing next to her, visibly uneasy. (“How about the rest of us? Right-winging, bitter-clinging, proud clingers of our guns, our God, and our religions, and our Constitution.”) But they are rarities. As I write, Trump has been endorsed by just two members of Congress.2

The candidate who is second only to Trump in his ability to bestir conservative alarm, Texas Senator Ted Cruz, would be no better and indeed worse from the point of view of many in the GOP establishment. As is well known by now, most of his fellow Republican senators detest him, seeing in him a wholly self-serving figure whose word is worth nothing. I think we can be absolutely certain that Mitch McConnell, the Republican Senate leader whom Cruz has openly criticized on several occasions, would much rather spend four or eight years calling Trump “Mr. President” than having to genuflect to Cruz. If forced to choose between the two, most establishment Republicans would take Trump. Both would be underdogs against Hillary Clinton, but the difference is that Trump would lose and just go away, while Cruz would lose and stick around, attempting to remake the party in his image, hauling it even further to the right. This is why they all hope so devoutly that Rubio can win some primaries and justify staying in the race long enough either to beat Trump head-to-head or at least deny him the delegates needed to secure the nomination going into the convention.

The fury that led to Trump’s rise has three main sources. It begins with talk radio, especially Rush Limbaugh, and all the conservative media—Fox News and, now, numerous blogs and websites and even hotly followed Twitter and Instagram feeds—that have for years served up a steady series of stories aimed at riling up conservatives. It has produced a campaign politics that is by now almost wholly one of splenetic affect and gesture. If you’ve watched any of the debates, you’ve seen it. The lines that get by far the biggest applause rarely have anything to do with any vision for the country save military strength and victory; they are execrations against what Barack Obama has done to America and what Hillary Clinton plans to do to it.

A second important factor has been the post–Citizens United elevation of megarich donors like the Koch brothers and Las Vegas’s Sheldon Adelson to the level of virtual party king-makers. The Kochs downplay the extent of their political spending, but whether it’s $250 million or much more than that, it’s an enormous sum, and they and Adelson and the others exist almost as a third political party.

When one family and its allies control that much money, and those running want it spent supporting them (although Trump has matched them), what candidate is going to take a position counter to that family and the network of which it is a part? The Kochs are known, for example, to be implacably opposed to any recognition that man-made climate change is a real danger. So no Republican candidate will buck that. This extends, of course, to practically the whole of Capitol Hill. Not long ago, I talked with Democratic Senator Al Franken of Minnesota, who explained how the Republicans’ fear of facing a Koch-financed primary from the right, should they cast a suspicious vote on climate change, prevented them from acknowledging the scientific facts. And what percentage of them, I asked, do you think really accept those facts deep down? “Oh,” Franken said, “Ninety.” He explained that in committee hearings, for example, witnesses from the Department of Energy come to discuss the department’s renewable energy strategy, “and none of them challenge the need for this stuff.”

This fear of losing a primary from the right is the third factor that has created today’s GOP, and it is frequently overlooked in the political media. Barney Frank put the problem memorably in an interview he gave to New York magazine in 2012, as he was leaving office:

People ask me, “Why don’t you guys get together?” And I say, “Exactly how much would you expect me to cooperate with Michele Bachmann?” And they say, “Are you saying they’re all Michele Bachmann?” And my answer is no, they’re not all Michele Bachmann. Half of them are Michele Bachmann. The other half are afraid of losing a primary to Michele Bachmann.3

Few Americans understand just how central this reality is to our current dysfunction. All the pressure Republicans feel is from the right, although they seldom say so—no Republican fears a challenge from the center, because there are few voters and no money there. And this phenomenon has no antipode on the Democratic side, because there exists no effective group of left-wing multimillionaires willing to finance primary campaigns against Democrats who depart from doctrine. Very few Democrats have to worry about such challenges. Republicans everywhere do.

Advertisement

This creates an ethos of purity whose impact on the presidential race is obvious. The clearest example concerns Rubio and his position on immigration. He supported the bipartisan bill the Senate passed in 2013. He obviously did so because he calculated that the bill would pass both houses and he would be seen as a great leader. But the base rebelled against it, and so now Rubio has reversed himself on the question of a path to citizenship for undocumented aliens and taken a number of other positions that are designed to mollify the base but would surely be hard to explain away in a general election were he to become the nominee—no rape and incest exceptions on abortion, abolition of the federal minimum wage, and more.

All this appears to have had the effect in this election of lowering the percentage of Republican primary voters who are willing to support the most electable candidate. In the past, for all the ideological teeth-gnashing, Republican primary voters have ultimately sent forward John McCain, Mitt Romney, Bob Dole. And perhaps they will still. The closest equivalent this time would be Rubio. We will see in due course if we have finally reached the point where the nihilists outnumber the pragmatists.

Democratic voters are less demanding, but not, these days, by a lot. Hillary Clinton was aware of the newly muscular economic-populist passions of the rank and file, and last year she made a series of moves that she surely thought would stand her in good, or at least improved, stead with a left flank that has never embraced her. She came out for paid family and medical leave. She proposed a set of reforms of Wall Street that would impose a graduated risk fee on large banks and a tax on high-frequency trading, among other measures, that was generally well received last fall. On a noneconomic matter, but one made salient on the left by the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, she called for sweeping criminal justice reforms and vowed to end the “era of mass incarceration.” She positioned herself clearly to the left of where she had been in 2008.

But she has clearly underestimated three things: first, the depth of anger on the left at the big banks and the very wealthy, especially in view of the continuing revelations of mortgage and other manipulations; second, the mistrust of her on her party’s left, especially on these issues; and third, Bernie Sanders’s skill as a candidate.

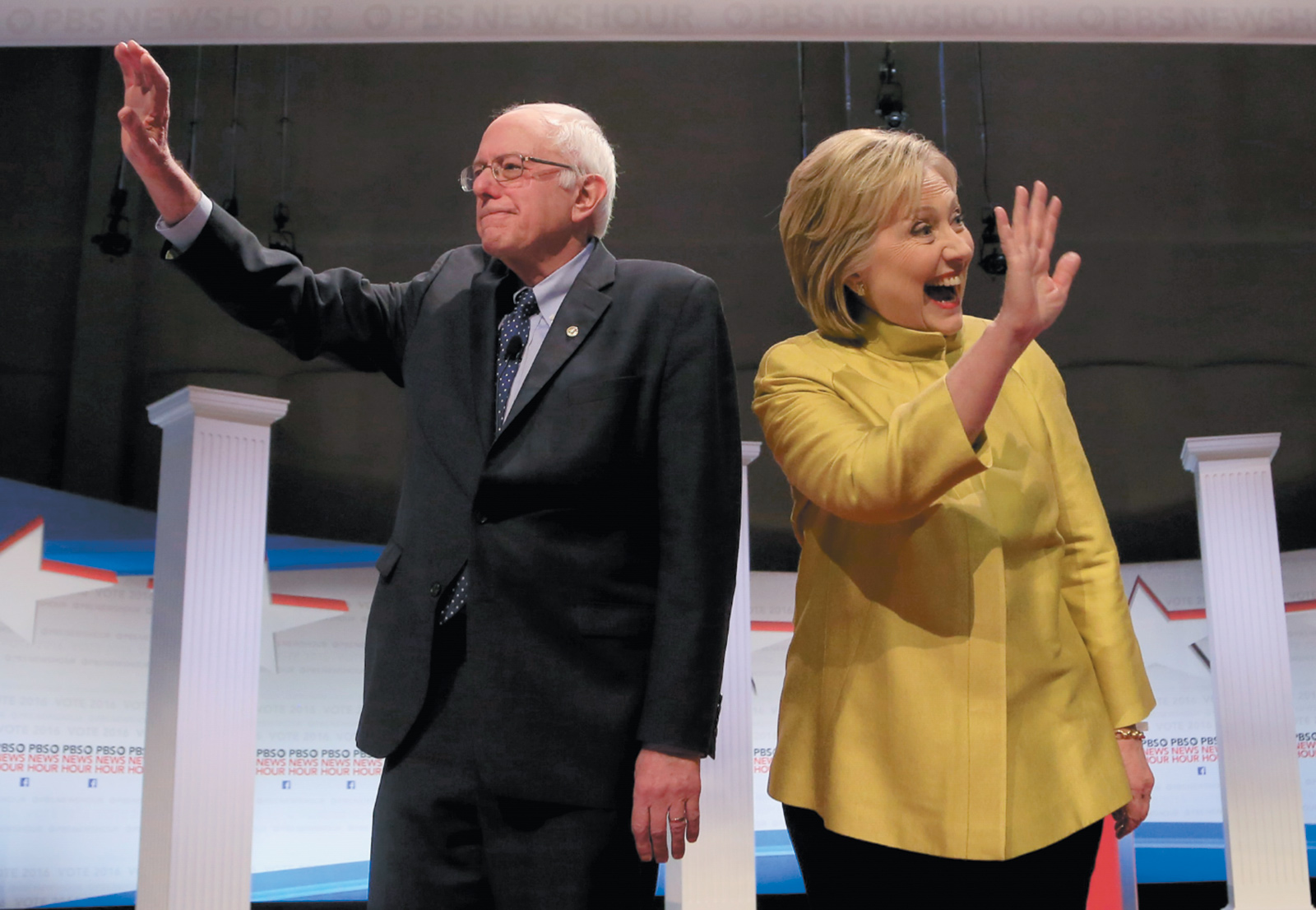

The vote totals reflect these realities. Clinton’s win in Iowa was as narrow as it could be. Sanders’s thrashing of her in New Hampshire, by twenty-two points, came in well above most expectations. And while she did beat Sanders by five and a half points in Nevada, stabilizing what could have been a near-disastrous situation, she is still a long way from satisfying her base.

Clinton has a number of problems, all of which might have lain dormant under different circumstances but all of which sprouted forth as the voting began. The main one, as far as Democratic primary voters are concerned (a November electorate may well have different sources of unease), has to do with the authenticity of her newly held progressive positions.

Her overtures to the left, on close examination, were basically sound but they were still embroidered with the caution that has been her habit. For example, while her Wall Street package won some praise on the left, including from Elizabeth Warren, Clinton stops short of reinstating Glass-Steagall regulation of banks, which has become one of those symbolic positions for people on the left. On paid family leave, there is a bill in the Senate that would finance it by imposing a 0.2 percent payroll tax on workers and employers. It has fairly broad Democratic backing, but Clinton doesn’t support it. Her proposal would be funded by a higher tax on the wealthy only, because she wants to be able to say that she will raise no taxes on anyone making less than $250,000.

As for Sanders, as effective as he has been, he has his own flaws, which turn chiefly on whether he is electable. His partisans point to the general election head-to-head matchups in which he fares as well as, or better than, Clinton against Trump and Cruz and Rubio. But those polls don’t mean much. The Republicans haven’t spent a dollar attacking him yet, and if he were the nominee, they and their affiliated groups would spend between $500 million and $1 billion doing so.

How would he hold up under that barrage? There is his socialist background, the honeymoon trip he and his wife took to the Soviet Union, and all that. But Republicans might not even have to go there. The tax increases that would be entailed by Sanders’s programs, including his Medicare-for-all plan, have recently been shown to be enormous, requiring, according to some estimates, a top marginal tax rate of as much as 84 percent. Sanders argues that the trade-offs he proposes for expanded Medicare—taxes but no deductibles or copayments, not even for dental care and optometry—would save people thousands of dollars a year. In some cases they surely would. But as the health care expert Harold Pollack has pointed out, Sanders’s plan would in effect require a doubling of federal income tax collections.4 The attack ads would doubtless say something like: “Bernie Sanders wants to double your taxes, limit your choice of doctor, and turn America into Cuba.” Times may have changed this country, but have they changed enough that 51 percent of voters will vote against such claims?

Finally, Sanders would present for the Democratic establishment some of the same problems that Trump and Cruz would present for Republicans. Very few elected Democrats would endorse Sanders enthusiastically, because they would calculate that being too close to Sanders would hurt their own reelection chances. So the Democrats too would be fractured, and perhaps for a very long time.

The results from Nevada may have settled these questions. Yes, Clinton led there by twenty-five points last fall. But in the run-up to the caucuses, Sanders outspent her nearly two-to-one on television ads and had more organizers and offices around the state. He had a lot of momentum and a mostly favorable press. But it seems that by and large, the African-American and Latino voters stuck with Clinton. (The latter preference was hotly disputed based on an “entrance poll” showing that Sanders won among Latinos, but those polls can be shaky, and the result didn’t jibe with a closer inspection of the precinct-level tallies; the Clinton campaign claimed that she won 207 delegates in the state’s majority-Latino precincts, and Sanders won 130.)

I spent two days in Nevada, where I spoke with union leaders and politicians and some regular voters. On the afternoon before the voting, I sat down with Geoconda Arguello Kline, the leader of the powerful Culinary Local 226, which represents 57,000 workers in most of the hotels and casinos. Interestingly, one of the non-union hotels belongs to Donald Trump; the union won an election there, but Trump has yet to negotiate a contract, although Arguello Kline noted that Trump did recognize the union at a resort he owns in Canada.

Local 226 has members from 167 countries—Arguello Kline herself is a native of Nicaragua who came to the States in 1979 just before the Sandinista revolution—and is 56 percent Latino. The union endorsed Obama in 2008, but Clinton won the state. This time, the union did not endorse anyone. “An endorsement is a major commitment,” Arguello Kline told me. “You have to do everything for your candidate.” She said the union was busy with organizing and citizenship drives. It also seems apparent that her membership was split along generational lines. There’s no real way to measure these things, but the results suggest that Clinton probably ended up carrying a majority of the union’s members. At the caucus sites that were set up along the Strip inside the casinos, Clinton won most of them handily.

On caucus day itself, I went first to a caucus site at a middle school about two miles west of the Strip. Caucuses aren’t as democratic or as reflective of overall public sentiment as regular old primaries, and most states that have caucuses choose them simply because they’re less expensive to run. Nevertheless, there’s still something moving about seeing hundreds of people line up for an hour or more to take part in this ritual. I spoke there with Representative Dina Titus, who has represented Nevada’s first congressional district since 2013. A native Georgian who has not lost her accent despite forty years’ residence in Sin City, she’d spoken the night before at a Clinton rally I attended, where I wondered if there was enough enthusiasm.

I asked Titus: In your experience, when Democrats tell you they’re against Clinton, what’s the main reason they give? “Oh, idealism,” she said. “The people who support Bernie just like living the dream.” She explained that she often heard from people that Sanders was saying what they wanted to hear a Democrat say, and she concluded: “He’s the grandfather who says ‘Let’s go get ice cream,’ and Hillary is the grandmother who says ‘Do your homework first.’”

Nevadans chose homework, which was a mild surprise since according to the entrance polls electability ranked only fourth as a candidate’s most important quality. In any case Clinton’s win there, combined with what at the time of this writing was expected to be a big win in South Carolina on February 27 and then a near sweep of the dozen states voting on March 1, should begin to move her ineluctably toward the nomination.

Ineluctably, but I doubt smoothly. The FBI investigation of her e-mails is ongoing, and no one quite knows what the bureau will have to say about all that, or when. She will commit other unforced errors; she always does. And Sanders isn’t going anywhere. He will have the money, and enraptured supporters, to campaign through June. We should expect that he’ll do so. He has an audience far larger than any he’s ever had, and he won’t give that up until he absolutely has to. And if something goes haywire in Clintonland, he’ll still be standing.

So Clinton, even if she is racking up wins and delegates, has weeks or months of work ahead of her to convince more liberal voters that she means it. And on the Republican side, it may be that if indeed Clinton appears to be advancing toward the nomination, the pragmatists will finally start to outnumber the nihilists. Once the Republican race gets down to the big three of Trump, Cruz, and Rubio, we will see if Rubio can get his thirty-four percent in such contests.

He has certainly done a fine job of spinning a gullible press corps. He tried to claim that his second-place finish in South Carolina was somehow a win, and CNN for one obliged him with a report that could have been produced by Rubio’s press office. But his double-digit loss to Trump fell far short of the expectations that Rubio’s own campaign had set up. He had the support of the state’s three best-known GOP politicians—Governor Nikki Haley, Senator Tim Scott, and Congressman Trey Gowdy, chair of the Benghazi hearings—and a campaign staff with deep South Carolina connections. Besides which, his campaign had spent January cultivating donors by telling them he would win the state.

Nevertheless, perhaps the question of electability will eventually come to the fore on the Republican side. But the last few months have made all predictions an iffy business this time around. The workings of fear tend to be furtive.

—February 25, 2016

-

1

“Against Trump,” National Review, January 21, 2016. ↩

-

2

After this article went to press, New Jersey governor Chris Christie endorsed Trump. ↩

-

3

See Jason Zengerle, “In Conversation: Barney Frank,” New York, April 15, 2012. ↩

-

4

See Harold Pollack, “Here’s Why Creating Single-Payer Health Care in America Is So Hard,” Vox, January 16, 2016. ↩