1.

Eileen Myles’s new and selected poems are titled I Must Be Living Twice, a phrase that any poet past the midpoint and looking back might utter, surprised to find a fund of work on the page as robust and spontaneous as any “real” life she lived. But Myles’s poems set a bar for openness, frankness, and variability few lives could ever match; and so in her work, the surprise second life is actually the one lived off the page, refracted through decades of Myles’s astonishingly vivid lines.

The solemnities of art are, in Myles, everywhere undermined: “I like to get really stoned/and revise everything I’ve ever done/Leaning/against the refrigerator,” she writes in “La Vita Nuova.” You’d score that a win for life, if it weren’t for the fact that we hear about it in lines of verse. The title alludes to Dante; “leaning”—with the unshowy pun on Myles’s first name—is among the most important words in American poetry, handed down to Myles from two of her New York heroes: Whitman (“I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass”) and especially Frank O’Hara in “The Day Lady Died” (“I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of leaning on the john door in the 5 Spot”). It is deeply characteristic of her that the most Dionysian moments are also her most vocational. Only a poet who agreed with Robert Frost that poems are “play for mortal stakes” would boast about getting stoned and heedlessly working on revisions.

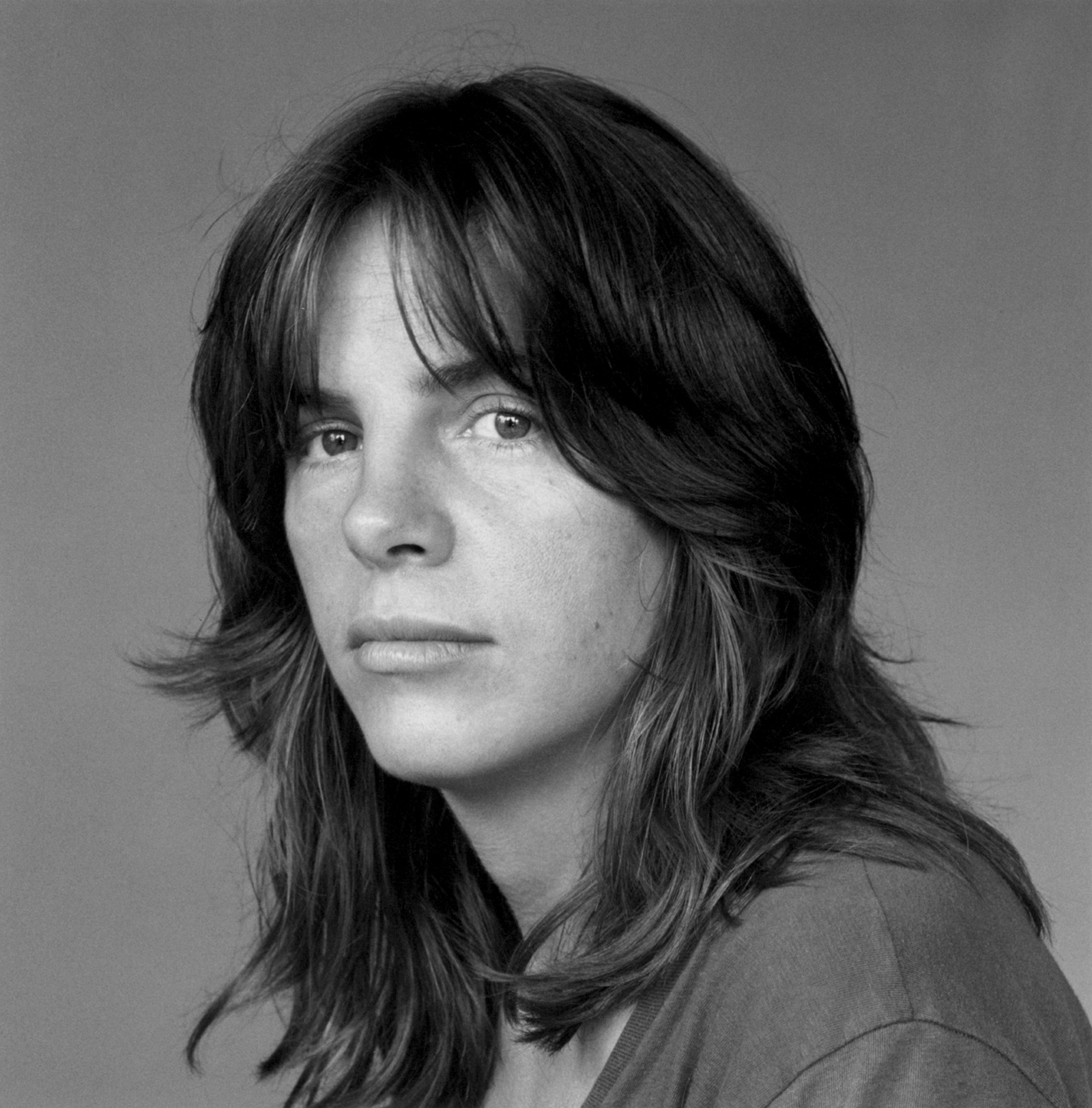

Myles’s work has always been uncompromisingly frontal, a face-forward presentation of herself, simultaneously vulnerable and scrutinizing. If you look at her, she looks back. Her classic autobiographical novel from 1994, Chelsea Girls, has been reissued to accompany the volume of poems. Photographs of the author appear on the front covers of both volumes. In the black-and-white Robert Mapplethorpe photo on the cover of Chelsea Girls, Myles looks young, ethereal, maybe high, and, perhaps most of all, dazzled—daunted to be Mapplethorpe’s subject. It could be an album cover; it isn’t the only detail of Myles’s life and work that calls to mind Patti Smith. In Catherine Opie’s recent color portrait of Myles on the cover of the book of poems, Myles looks brash, handsome, bemused—and, most importantly, neither male nor female (or both at the same time): “the gender of Eileen,” as she has remarked in interviews. Myles sits on a stool, her muscular forearms and battered knees in the foreground. On a lark, in the 1990s, Myles ran for president as a write-in candidate. This photo looks for all the world like a presidential portrait: switch out the wardrobe and readjust the posture a little, and Myles could be Calvin Coolidge or Ronald Reagan. There is a hint in this about the lines of formality and casualness in her work, the mutual reliance of spontaneity and calculation.

Myles has “lived twice” in several important senses. She is a poet perhaps best known for a book of prose: a memoir lightly disguised as a novel, itself a kind of double exposure. She’s lived as a straight woman and as a lesbian; she is an addict who has long been sober. She is associated with Boston, where she was raised, and with New York, where she has, for decades, been a citizen of the East Village and various downtown art and poetry scenes.

Many of her recent poems call to mind, consciously, her earlier work, and this new book is made up mostly of poems being published in a book a second time. She has been young; she is now sixty-six, an age young people since the Beatles associate with being old. Her life is marked by new beginnings, her poems by retrospection and “self-thievery.” One thinks of Hart Crane, a great influence upon her, and of his marvelous phrase “new thresholds, new anatomies.” Her poems are chronicles of barriers first feared, then crossed, and of the physical and sensual pleasures and pains that followed. Her life is a series of crossed thresholds; her poems, so often about the ups and downs of having a body, are themselves bodies, “anatomies” formed in the aftermath of transformation.

Her work explores the power of look-alikes doubles, pairs, and substitutes. “All these rhymes all the time,” she writes in “Smile”: “I used to/think Mark Wahlberg was family.” How strange, in a life this courageously individuated, to find oneself duplicated in the voice and jawline of a stranger: Wahlberg and Myles indeed look alike, and carry the same broad working-class Boston accent, which Myles liked to break out, she has said, when workers showed up at her house in Provincetown, “to get the guys to not fuck us over.”

Advertisement

“I am the daughter/of substitution,” Myles writes:

my father fell

instead of the dresser

it was the family

joke, his death

not a suicide

but a joke

Elsewhere, Myles describes her father’s accident in more detail: he lands at her feet, which at first seems like an absurdist prank. But Myles’s father didn’t die right away. In Chelsea Girls, she describes the job of “watching” him as he slowly failed, lying on the couch and smoking. She has been punished that day at school; at home, she must minister to her father in front of her friend, Mary McClusky, who has stopped by after school:

Dad, the worst time ever with you was when Mary McClusky was over and you had your red lumberjack shirt on and you were lying down and you had those awful headaches which kept pounding and made you always look like you were going to cry, and you put your two fingers to your lips…. You couldn’t talk and you kept making that two-fingered gesture even though I felt like it wasn’t what you wanted I knelt down and kissed you in front of Mary which was hard because she is such a tomboy. “No, God damn it, a cigarette.” “She kissed him,” Mary laughed. Myles kissed him…. I think I just wanted to kiss you in front of Mary because you were lying there sick.

Tense here is everything: “I knelt down and kissed you in front of Mary which was hard because she is such a tomboy.” On the plane of writing, Myles reminds us, everything that was still is, and everything that is already was. Insight that arrives decades later is inserted into the original scene; while the intensity of response, the shame, the mockery—everything ostensibly in the past—represents itself. This is why the word “representation” is so crucial to what an artist like Myles does.

A “daughter of substitution” sees multiple forms of herself distributed across the years, and concludes—or fears she must conclude—that she doesn’t exist at all, if existence requires a single, unique manifestation, consistent across the arc of time. “Eileen” becomes a fully fledged artist as a sign of difference from her childhood; but standing out, for a working-class girl from Boston, educated in Catholic schools, is an affront to authority, which reasserts its power through forced reiteration:

Eileen spoke

so well about the creative

process. Maybe she would

like to do it again.

That’s the way nuns run a classroom (I’m a working-class New Englander, too; I, too, was taught by nuns and priests): if you speak out of turn, or distract your neighbor, you have to repeat it in front of the whole class. Authors are asked, at readings and at conferences, about “the creative process”: a person from Myles’s background never gets used to speaking up publicly, since the classroom fear of disobedience and swift reprimand is so ingrained.

Later in the same poem, “A Debate with a Glove,” the demand for recitation, transported to adulthood, becomes a remembered prelude to sex. It is “five” after a night out; Myles asks to be “alone” in bed with “my sex” and “my beautiful hands.” Autoerotic fantasy is internalized seduction: a single self contains both pursuer and pursued. We are in what I take to be a remembered pickup bar, crossing the invisible line when late in the night becomes early in the morning. Here the prompts for answers and the answers themselves are part of a single weave:

Tell me something else.

Was I married.

Have I been here

before. Why am I

always in between.

Is it late or

is it early.

Money, I could

give a shit.

Fame, forget it.

An authenticity

that rattles

my bones. Is

it two of

everything

or one.

It is none.

Two, one, none: this little countdown—to orgasm, to insight—is also a vanishing fuse. The ecstasy subsides and guilt takes its place:

I’m sorry we

went to war

with you &

broke your

bridge.

The aftermath of sex becomes the aftermath of a war, with Myles the baffled aggressor who has scored a regrettable victory. What kind of token gesture of reconciliation will suffice? “I’ll fix it now,” she writes: “Should/we get married/or something?”

Of course the poem is the reconciliation, the marriage, the bridge: the fix. In Inferno (A Poet’s Novel), published in 2010, Myles tracks writing back to the people, situations, accidents, misunderstandings, ill-advised arrangements, and schemes that threaten to trip up the poems they paradoxically inspire. These makeshift conditions are always shifting, always comically adverse, and always, when you meet them in poems, offered in the spirit of friendly polemic. The poet is supposed to be a “beautiful stoner boy or an intellectual,” as Myles put it in a recent Paris Review interview:

Advertisement

There’s a whole female industry engaged in materially supporting the illusion that the artist doesn’t work directly on his legacy, his immediate success. He’s just a beautiful stoner boy or an intellectual. All thought. No wife? I like turning that illusion inside out. And making the work be literally about the field and the failures and even the practice. I wrote about these things in Inferno because Dante did. We should let the writing world and its ways of distributing awards be part of fiction. We should expose the very cultural apparatus that is affecting the reception of the book you’re reading. What’s dirty is that we’re not supposed to talk about how it has sex and reproduces.

Inferno is the right title for this book, its vivid particulars seen under the sign of tragedy (among many other things, Myles is a great poet of the New York of the 1970s and early 1980s that ended forever with AIDS). Myles moves into her first apartment in New York, on 71st and West End, with a roommate, Alice, who is “tapped into a lesbian network that funded their activities by selling subway slugs.” A guy at Myles’s work buys a bag, then proposes that the two of them have sex, have a baby, and sell it for $15,000. This kind of absurd profiteering suggests how tenuous it is to write and sell poetry. It exists on an economic continuum that includes counterfeit subway tokens and for-profit pregnancy.

2.

“Why am I/always in between,” Myles asks in “A Debate with a Glove.” Chelsea Girls is a dynastic book, beginning with the death of Myles’s father and ending with the death of a father figure, often couch-bound like her own father, whom she tended: the great New York School poet James Schuyler, whom Myles, short on cash, cared for in his last period, while he was living in ennobled squalor in a room at the Chelsea Hotel.

Myles is somewhere “in between” these two men, “living twice” by helping both of them die. The abrupt violence, even gore, of her real father’s death, landing at her feet (though he died somewhat later of a cerebral hemorrhage), is replaced, in this autobiographical novel, by Schuyler’s own slow deterioration. He had lost nearly all his friends and burned down his apartment with a cigarette. The picture of Schuyler is unbelievably tender and weirdly clinical, like something a queer Hazlitt would have written if he were a dyke poet tending to an old queen:

Hello Dear. Sometimes I came in and he was sitting on his chair by the bright window. He got up early. He told me that, but I could also surmise it from the number of cigarettes in the ashtray which he never dumped, and how much spilled Taster’s Choice was on the kitchen counter. (John [Ashbery] says Taster’s Choice is the best. The emphasis on John meant both that it was a funny thing to have an opinion on and a useful tip that one should take.) I saw his dick a lot. Probably more than any other man’s in my life. It wasn’t small, it was kind of large. As I would narrate my nightly voyage he would tell me about all his affairs in the forties and fifties and invariably these often very famous men who were practically myths now would be rated: He was like sleeping with a reptile. Really icky. Edwin. He had a lovely dick. I’d be standing over him holding a dirty dish and figured to leave the silence alone. Well yours looks pretty good I might say as it nudged out of his boxer shorts.

The scene mixes desire and disheveled interiors as a way of stopping time: Schuyler is both father and child; Myles is both liberated to describe her “nightly voyage” (voyages have destinations; Schuyler’s apartment was hers) and held subservient, this time by choice, in a little world where women were somewhat beside the point. The cigarettes are units of time, much like lyric poems, their intervals reckoned differently by old and young, the healthy and the sick.

The episode ends with Myles reading one of her new poems to Schuyler, who is at this point sound asleep. Myles discovers the poem on a “damp” napkin when she jams her pay, three dollar bills, into her pants. It might have occurred to Myles not to read a poem that includes the line “the old are very ugly” to Schuyler, but this is the point—the amalgam of repulsion and love, the poem severing a transaction it creates:

When you see them

smoking a cigarette, it’s

like the tip of the iceberg.

And their boozy wrinkles

under their eyes. You

know I like this evening.

…Your

beauty, mine,

our drinks, I wonder

if I should catch

up, you’re drinking

faster than me, Oh

I guess I’ll get

another vodka tonic

and see how the evening

goes. Clink-Clink.

It’s a charming enough poem; and, I would guess, it worked at what it was intended to do: lure this girl into bed. But that’s not why Myles reads it to Schuyler, or why she quotes herself reading it to Schuyler on the last pages of her autobiographical novel. The poem is homage, only deepened by its ostensible cruelty to the old iceberg in the chair, his “boozy wrinkles” revealing a lifetime of experience. It is written in Schuyler’s ribbon-like short lines, haltingly enjambed; it reminds me especially of Schuyler’s heartbreaking poem, for me his greatest: “This Dark Apartment.”

With Myles and her generation of poets, we have a class of artists whose identity was, for a long time, wrapped up in their being junior, their ire and adoration directed upward toward the big talents that preceded them. Myles is sometimes misunderstood on the basis of a single poem, which depressingly keeps cropping up in reviews of these volumes—mine, alas, being no exception. “On the Death of Robert Lowell” is her blurted, blasphemous, punk, and utterly Bostonian elegy for Lowell:

O, I don’t give a shit.

He was an old white-haired man

Insensate beyond belief and

Filled with much anxiety about his imagined

Pain. Not that I’d know

I hate fucking wasps.

The guy was a loon.

Signed up for Spring Semester at MacLeans

A really lush retreat among pines and

Hippy attendants. Ray Charles also

once rested there.

So did James Taylor…

The famous, as we know, are nuts.

Take Robert Lowell.

The old white-haired coot.

Fucking dead.

Now Myles is older than Lowell when he died, and enjoying her greatest moment of accomplishment and fame. Her very presence in the world is a form of activism, but her work, when studied with care, is also political in the sense that it gives evidence of one of the richest and most conflicted human hearts you’re likely to find. When, many years from now, she passes away, may she be elegized rudely by some brat clearing the nettles from her path, just the way she did with Lowell (and, in a more complex gesture, with Schuyler). This kind of schoolyard insult—“The guy was a loon”—is almost hilariously transparent as an expression of desire, and it is part of what the art’s all about.