When Hillary Clinton started losing young women voters to Barack Obama in the Democratic primaries of 2008, the common wisdom among her supporters was that she had messed things up by not “running as a woman.”1 She had refused to grant any particular significance to her gender; she had sought out the endorsements of generals; she had projected “masculine” commander-in-chief qualities at the expense of showing her warm, emotional, “feminine” side. And the result of all this, it was said, was that she had fatally squandered the inspirational appeal of her bid to be the first woman president.

In Broad Influence, a book about women’s impact on the American workplace, Jay Newton-Small recalls Clinton’s public tearfulness on the eve of the 2008 New Hampshire primary as the one salutary occasion during the campaign when Clinton dropped her tough-guy affectations and became a truly effective, woman-friendly candidate. According to Newton-Small her strategist, Mark Penn,

feared this lapse in discipline would end not just her candidacy but potentially her career. But voters didn’t see it that way. After months of wooden, military Hillary, they saw her as a woman with whom especially female voters could empathize. Her tears were a turning point: primarily thanks to female voters, Clinton won New Hampshire 46 percent to Obama’s 34 percent.

The notion that Clinton’s campaign style in 2008 was an imitation of maleness—a shrouding of her authentic womanly self—is testament not only to a strong streak of essentialism that persists in modern feminism, but also to some rather wishful thinking about who Clinton “really” is. A more accurate summation of her strategy that year (and of why young female Democrats didn’t vote for her) is that she ran as a conservative woman.2 And given her history of hawkish foreign policy positions both before and since—her votes for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, her enthusiasm for sending “the hard men with guns” into Syria, and so on—there is no reason to believe that this tough, “military” Clinton was any less authentic than the one who became briefly misty-eyed in a New Hampshire coffee shop.

At any rate, Clinton has now seen the error of her ways. The first clear indication that she would be playing up her femaleness and its putative attendant virtues in this election came two years ago with the publication of her memoir Hard Choices. The book opens with an account of Clinton taking Obama to task for the sexism she endured during the 2008 primaries3 and ends with a chapter on her efforts at the State Department to “knit gender into every corner of US foreign policy.” In between, it fairly brims with “aren’t women amazing?” sentiments of the sort one finds cross-stitched on decorative cushions.4

Doubtless, whatever platform Clinton had run on this year, her campaign would have had some sort of inspirational “woman power” theme. Since circumstances have required her to run “to the left” against a man whose leftist credentials are significantly stronger than hers, she has been relying heavily on her femaleness and feminism to make up for whatever she lacks in progressive bona fides. By placing women’s rights and the rights of other identity-based groups at the center of her campaign, she has been seeking to draw a contrast between Sanders’s focus on class and income inequality and her own sensitivity to “racial inequality, sexist inequality, homophobic inequality.” There is no significant difference in her and Sanders’s positions on criminal justice reform, women’s reproductive rights, or LGBT rights, but the suggestion is that she is committed to these issues in a way that an old, white male democratic socialist can’t be: “We all need a champion in the White House,” she said earlier this year at a dinner marking the forty-third anniversary of Roe v. Wade, “and not just someone who says the right things.”

That Clinton will be a necessarily more effective champion of gender equity than Sanders, that she has a stronger track record on women’s rights than him, is a crucial part of the feminist argument for her candidacy and also its weakest. Clinton has certainly been pushed during this campaign to take what are, for her, unusually bold, feminist positions on women’s issues and, if elected, she may well feel obliged to carry some of that boldness with her into her administration. But it is dishonest to pretend that her prior record offers any sort of guarantee of a “pro-women” presidency.

Notwithstanding the work that she did at the State Department in the service of “global women’s concerns” and her much-vaunted “women’s rights are human rights” declaration in Beijing in 1995 (a speech that her supporters characterize somewhat implausibly as a watershed moment in feminist history), Clinton’s record as an advocate for women is distinctly uneven. Whenever feminist principles have been at odds with what is politically expedient, expediency has tended to win the day. In the 1990s, she vigorously supported her husband’s welfare reform bill—a piece of legislation that has probably done more to immiserate the lives of poor women—particularly poor black women—than anything else over the last twenty-five years.5 In 2005, when it was politically convenient to distance herself from the pro-choice plank of the Democratic platform, she lectured family planning activists on what was regrettable and even “tragic” about abortions:

Advertisement

I, for one, respect those who believe with all their hearts and conscience that there are no circumstances under which any abortion should ever be available.

Twenty months ago, she told Christiane Amanpour in a CNN interview that federal legislation on family paid leave was not a feasible option: “I don’t think, politically, we could get it now.”

In addition to emphasizing what her presidency would do for women, Clinton and her surrogates have been working hard to invoke what it might mean for women in a grander, symbolic sense. As a woman president, she tells us, she wouldn’t just work for radical change, she would be radical change: “Who could be more of an outsider than a woman president?” Or, as Madeleine Albright has put it: “People are talking about revolution. What kind of revolution would it be to have the first woman president of the United States?”

This idea that her gender is in itself a progressive value, that the mere presence of a woman in the White House would be transformational, was recently taken up by Suzanna Danuta Walters, who explained in The Nation why she intended to vote for Clinton “less for her specific political positions…than for the iconic value of electing the first woman president of the United States”:

No, the stalled revolution for gender equity won’t be won simply by installing a woman in the White House. But it may help animate conversation, instill fierce female pride and inspire young girls the world over…. The idea that Hillary’s victory would be “merely” symbolic underestimates the profound importance of symbolism…. It is substantively different to have a woman president advocating for gender equality as opposed to having a man do so, just as it is to have a black president advocating for racial justice—because gender and racial difference live in and through our marked bodies.

Symbolism is important, of course. And the desire to do something about women’s chronic underrepresentation in American politics is not, as some of Sanders’s supporters have rashly suggested, simply infantile or “narcissistic.” (Those who suggest as much were noticeably less scornful about the desire of black voters to elect a black president in 2008.) But if one is going to use Obama as an example of a president’s symbolic import, it seems only reasonable to acknowledge that his administration has coincided with the most drastic decline in the economic fortunes of African-Americans since World War II. In 2009 when Obama took office, the black poverty rate was 25.8 percent, and by 2014 it had risen to 26.2 percent. Between 2010 and 2013, the median wealth of white households increased by 2.4 percent, while black families’ median net worth declined by 34 percent. By any metric you care to mention—home ownership rates, unemployment rates, incarceration rates—the quality of African-American lives has either remained the same or sharply deteriorated during Obama’s time in office.

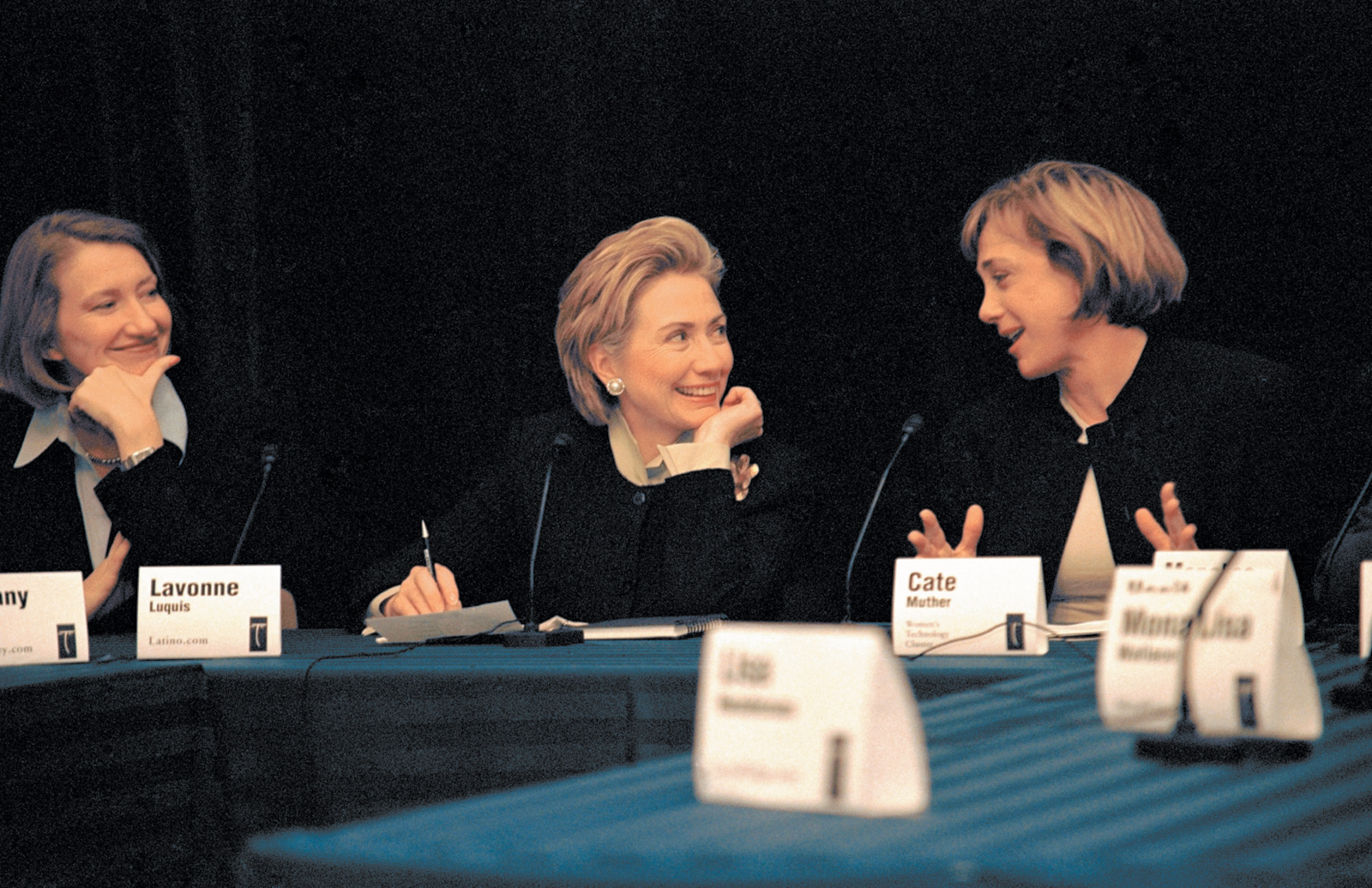

Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Hillary Clinton at a roundtable discussion about women and technology, San Francisco, March 2000. At left is Lavonne Luquis, cofounder of the Internet start-up Latino.com; at right is Cate Muther, founder of the Women’s Technology Cluster (now called Astia), an incubator for female entrepreneurs in the high-tech industry.

Thus far in this election, Clinton’s attempt to purvey gender as a guarantor of progressive or feminist values, her strenuous attempts to “connect with” young women via Bitmojis and SnapChat videos and endorsements from Lena Dunham, have proved much less effective than she and her supporters expected. Given the choice of a man who promises to reinstitute Glass-Steagall, make college education free, and provide Medicare for all, and a woman who will animate conversations about gender equity, large numbers of female Democrats have chosen the former. Just as in 2008, Clinton has found herself rejected by her “natural constituency” as a less inspirational candidate, a less plausible agent of change than her male opponent—and this time, it’s rather more galling, because the opponent in question is not an elegant, younger black man who can sing Al Green songs, but a seventy-four-year-old white man with the oratory style of a staff sergeant.

In Iowa and New Hampshire, Sanders took 80 percent and 82 percent respectively of votes among women under the age of 30; in Nevada, he took 73 percent of the votes among women under the age of 45. In South Carolina and several of the states that voted on Super Tuesday, Clinton did much better with young women voters, but even in these contests, it was her popularity among minority voters of both sexes rather than gender solidarity that proved crucial to her victories.

Advertisement

Clinton’s older female supporters, who have set so much store by Clinton running “as a woman,” have responded with some exasperation to the failure of the gender strategy. It is not enough that she is going to secure the nomination as the sensible, electable, pragmatic choice. They want her to win as the revolutionary choice. Their default analysis is that young women who don’t favor Clinton haven’t lived long enough, haven’t experienced enough sexism, to do the “radical” thing and vote along gender lines. “Here’s what I see,” Debbie Wasserman Schultz, chairwoman of the Democratic National Council, told The New York Times in January: “a complacency among a generation of young women whose entire lives have been lived after Roe v. Wade was decided.” “More time in a sexist world, and particularly in the workplace radicalizes women,” Jill Filipovic wrote in a New York Times article in February. “You think the work is done. It isn’t done!” Madeleine Albright told young women at a Clinton rally in New Hampshire, before trotting out her trademark bon mot about there being a special place in hell “for women who don’t help each other.” Gloria Steinem, speaking to talk show host Bill Maher, proposed that young women who voted for Sanders were following the lead of young men: “When you’re young, you’re thinking, ‘Where are the boys? The boys are with Bernie.’” (After the Iowa caucuses of 2008, Steinem famously suggested that young women who voted for Obama were seeking to “deny or escape the sexual caste system.”)

The widespread disdain and irritation that these comments have elicited both in the media and among young women voters appear to have alarmed the Clinton camp somewhat. In recent weeks, the campaign has grown markedly more reticent about making direct appeals to the sisterhood. Nevertheless, among Clinton’s feminist supporters, the disheartening tendency to characterize any resistance to her candidacy as either sexist or the product of false consciousness persists. The reaction to Doug Henwood’s anti-Clinton polemic My Turn is a case in point. Henwood is not a Sanders fan—“If by some miracle Sanders were to be elected, the establishment would crush him,” he writes—but he doesn’t think Clinton is any sort of progressive or even much of a feminist, and he believes that those who claim otherwise are

proof that Democrats, especially liberal Democrats, are the cheapest dates around—throw them a few rhetorical bones, regardless of your record, and they’re yours to take home and bed.

Henwood takes a fairly measured view of his subject’s political expediency: she’s not the devil, just “a standard-issue mainstream—or, as we used to say in bolder times, bourgeois—politician.” One can argue with some of what he has chosen to include in his indictment. Several of the stories he tells have the meretricious, gossipy, fundamentally implausible quality of the anecdotes one is apt to find in an anti-Clinton screed by Ed Klein. (Even if we could be sure that Clinton sulked when told that she couldn’t have a swimming pool on the grounds of the Arkansas governor’s mansion, or that she once told a member of her security detail to “fuck off” for no good reason, these tales aren’t as telling or as damning as Henwood seems to think.) Nevertheless, his book is, for the most part, a solid and persuasive guide to what has been characterized as shady or shabby or unprincipled in Clinton’s political career—from her work at the Rose Law Firm in the 1970s on behalf of corporate customers of utility firms to the troubling evidence that corporations and foreign governments that made large donations to the Clinton Foundation received preferential treatment from the State Department during her tenure as secretary of state.

Tellingly, Clinton supporters have focused their response to the book almost exclusively on its cover illustration—a painting by the artist Sarah Sole of a grim-faced Clinton pointing a gun at the reader. (This has been condemned as “gross,” “disgusting,” and evidence of Henwood’s discomfort with powerful, ambitious women.) Insofar as anyone has troubled to engage with the book’s contents, it has been only to point out that male Democrats do bad things too and to suggest that Clinton’s sins must be seen in a “gendered context.”

The latter is a way of saying that Clinton has been under greater pressure to compromise her liberal ideals, or to hide them beneath a Third Way bushel, because of the sexist fear and loathing she has inspired as a female politician. As Rebecca Traister wrote in The New Republic last year:

America did not much like this woman when she first came to us: ambitious and tough and liberal and feminist and interested in social progress and civil rights and reforming the world for women and children across classes…. She was derided for being ugly, for being mannish, for being frigid, and for consulting with the ghost of Eleanor Roosevelt…. And so, in her quest to become a mainstream, powerful politician, she contorted; she bent and stretched to be more like what the people could stomach.

Well, the quest to become mainstream and powerful is generally what motivates politicians to betray their youthful ideals. And while there’s no doubt that Clinton has faced a lot of sexism during her time in public office, it seems a bit of a stretch to explain all the less appetizing parts of her record as efforts to appease the forces of right-wing misogyny. Whatever led her to vote for the Patriot Act, or to take $675,000 in speaking fees from Goldman Sachs, it surely wasn’t the patriarchy.

Clinton herself has a long-standing habit of crying sexism when she wishes to dodge or deflect perfectly legitimate criticisms or questions. Her celebrated rebuke to reporters in 1992—“You know, I suppose I could have stayed home and baked cookies and had teas, but what I decided to do was fulfill my profession, which I entered before my husband was in public life”—gave the impression that she had been taken to task for being a working woman. In truth, she was using a righteous-sounding, feminist-sounding non sequitur to respond to an entirely pertinent inquiry about allegations of conflicts of interest that arose when she was working at the Rose Law Firm while her husband was governor of Arkansas.

Likewise, the famous remark she made in a 1992 interview regarding her husband’s alleged affair with Gennifer Flowers—“I’m not sitting here, some little woman standing by her man like Tammy Wynette”—suggested that she was defending herself against a charge of feminine servility, when in fact she was dodging a rather more astute question about whether she and Bill Clinton had come to “an arrangement”—whether, that is, she had decided to put up with his infidelity in the interest of furthering both their political fortunes.

She used a similar technique at a press conference in 1994, when she implied that the hostility and suspicion that had been directed at her during the Whitewater scandal were really expressions of society’s resistance to modern women:

We don’t fit easily into a lot of our preexisting categories. And I think that, having been independent, having made decisions, it’s a little difficult for us as a country, maybe to make the transition of having a woman, like many women in this room, sitting in this house.

Notwithstanding these rather cynical appeals to feminist sympathy, her trials as a female public figure have always inspired considerable fellow feeling in American women, particularly college-educated, white women. In 1996, Nora Ephron told a graduating class at Wellesley:

Don’t underestimate how much antagonism there is toward women and how many people wish we could turn the clock back…. Understand, every attack on Hillary Clinton for not knowing her place is an attack on you.

Indeed, several of the women who have declared their intention to vote for her in this election have cited their empathy with her sufferings, their understanding of what it is to be slighted and mocked and undervalued by a male-dominated system, as part of what has clinched their decisions. “It’s only as I approach middle age that I’m aware of what being a woman has cost me,…how naive I once was about sexism’s continuing salience,” Slate columnist Michelle Goldberg wrote recently:

In my twenties and early thirties… I didn’t know what it was to feel my status falling while that of the men around me rises. As it does, the unending contempt that Clinton receives for her clothes and her hairstyle, for growing older and stouter, have become personal to me in a way they weren’t eight years ago.

Horrid though it is that men have criticized Clinton’s figure and voice and called her “Hellary” and declared themselves repulsed at the idea of her going to the toilet—none of these things are very good or grown-up motives for electing her to the highest office in the land. It would be a fine thing to have a woman in the White House. But, really—let’s not put her there because someone once said she had “cankles.”

—March 9, 2016

-

1

In that year’s Iowa caucuses, Obama took 51 percent, John Edwards took 19 percent, and Clinton took 11 percent of the votes among women under the age of twenty-four. Clinton went on to lose the women’s vote in seventeen primaries, thanks largely to Obama’s popularity with African-American, single, and young women. ↩

-

2

“We are more Thatcher than anyone else,” Penn wrote to Clinton in a memo, shortly before the launch of the campaign. “The adjectives used about her (Iron Lady) were not of good humor or warmth, they were of smart, tough leadership.” ↩

-

3

“I understood that it arose from cultural and psychological attitudes about women’s roles in society, but that didn’t make it any easier for me and my supporters. In response, Barack spoke movingly about his grandmother’s struggle in business and his great pride in Michelle, Malia and Sasha and how strongly he felt they deserved full and equal rights. The candor of our conversation was reassuring and reinforced my resolve to support him.” ↩

-

4

For example, “A woman is like a teabag,’ [Eleanor Roosevelt] once observed wryly. ‘You never know how strong she is until she’s in hot water.’ I love that and, in my experience, it’s spot on.” Or this, from a female peace activist who Clinton met in Belfast in 1995: “It takes women to bring men to their senses.” ↩

-

5

Marian Wright Edelman, founder of the Children’s Defense Fund, who appeared last year in a Clinton campaign video, attesting to Clinton’s lifelong advocacy for “children and those left behind,” famously broke with the Clintons in the 1990s over welfare reform. “President Clinton’s signature on this pernicious bill makes a mockery of his pledge not to hurt children,” she wrote at the time. As recently as 2007 she told Democracy Now, “Hillary Clinton is an old friend but they [sic] are not friends in politics.” ↩