In Gernika, 1937: The Market Day Massacre, the historian Xabier Irujo reveals the hitherto unknown fact that the destruction of the historic Basque town of Guernica was planned by Nazi minister Hermann Göring as a gift for Hitler’s birthday, April 20. Guernica, the parliamentary seat of Biscay province, had not as yet been dragged into the Spanish civil war and was without defenses. Logistical problems delayed Göring’s master plan. As a result, Hitler’s birthday treat had to be postponed until April 26.

Besides celebrating the Führer’s birthday, the attack on Guernica served as a tactical military and aeronautical experiment to test the Luftwaffe’s ability to annihilate an entire city and crush the morale of its people. The Condor Legion’s chief of staff, Colonel Wolfram von Richthofen, painstakingly devised the operation to maximize human casualties, and above all deaths. A brief initial bombing at 4:30 PM drove much of the population into air-raid shelters. When Guernica’s citizens emerged from these shelters to rescue the wounded, a second, longer wave of bombing began, trapping them in the town center from which there was no escape. Low-flying planes strafed the streets with machine-gun fire. Those who had managed to survive were incinerated by the flames or asphyxiated by the lack of oxygen. Three hours of coordinated air strikes leveled the city and killed over 1,500 civilians. In his war diary, Richthofen described the operation as “absolutely fabulous!…a complete technical success.” The Führer was so thrilled that, two years later, he ordered Richthofen to employ the same bombing techniques, on an infinitely greater scale, to lay waste to Warsaw, thereby setting off World War II.

The morning after the bombing, Radio Bilbao broadcast a statement by the Basque president José Antonio Aguirre breaking the news to the world that Guernica had been annihilated by the Luftwaffe. The Basque and Spanish communities in Paris went into immediate action. When the poet Juan Larrea, the director of information at the Spanish embassy, heard the news from the Basque artist José Maria Ucelay outside the Champs-Elysées metro station, he jumped into a cab and drove to the Café de Flore where Picasso hung out.1

Four months earlier, the artist had been commissioned to paint a mural for the Spanish Republican pavilion at the upcoming Paris World’s Fair (L’Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne). As the most ardent promoter of Spain’s pavilion, Larrea, who had been instrumental in having Picasso appointed director of the Prado, realized that the obliteration of Guernica would provide the artist with the very subject he had been seeking. When Picasso claimed to have no idea what a bombed town looked like, Larrea replied, “like a bull in a china shop, run amok.”

Picasso had not as yet chosen a subject for his World’s Fair commission. As often before, he had envisioned his studio—a favorite setting and the vortex of the world—in a series of sketchy designs. Within a week of the attack on Guernica, he abandoned this theme and began working along the lines suggested by Larrea. By May 9, he had come up with a preliminary composition in a pencil drawing. It included most of the elements he had been playing around with but they did not as yet cohere into a viable concept. By May 11, the drawing would reemerge in full scale on the enormous canvas that would be the dominant feature of the Spanish pavilion.

Picasso’s Surrealist friends André Breton and Paul Éluard had been pressuring him for years to join the Communist Party, though both had been expelled from the Party four years before. The raised arm with a clenched fist seen in the first sketch of Guernica suggests that they were making headway. The Communist salute was also used in Spain during the civil war as a gesture of antifascist solidarity, but Picasso ultimately decided not to use it. He did not want his work to have an overly political, let alone Soviet tinge, and the fist soon disappeared from the composition. Insofar as he had any political views, Picasso was a passionate pacifist.

The artist would not become a Communist until October 1944 at the end of World War II. So impressed was he by de Gaulle’s triumphant return to Paris that he agreed to join the Gaullists, but after a dinner with some of them, he told his mistress Dora Maar, “c’est une bande de cons,” and immediately joined the Communist Party.

Picasso dealt with the subject of Guernica by personalizing it. Like most of his greatest works, it is pervaded with his own problems and preoccupations. Without understanding the artist’s votive obsession, scholars have not yet gotten around to seeing the image of his long-dead sister Conchita in the picture and the significance of Picasso’s broken vow he had made when she was ill.

Advertisement

In an article published in these pages, I described how Picasso, at the age of fourteen, had vowed to God that he would never paint again if Conchita, stricken with diptheria, survived.2 He did paint again and she died. Henceforth, many of the women in Picasso’s life would be sacrificed for his art.

Conchita makes an appearance in the first sketches for Guernica and would remain through all the subsequent variations. Hitherto, nobody has identified her, let alone explained her votive presence. Conchita no longer figures as a child, as she does in Minotauromachie, but has been transformed into an adult who thrusts out the sacred lamp clutched in her hand in order to have it lit by the Mithraic sun. This gesture was echoed in one of the five sculptures that appeared with Guernica at the Spanish pavilion: Picasso’s over-life-size 1933 Woman with a Lamp, which he had recast for the World’s Fair. So meaningful was this sculpture to Picasso that he would later arrange for a bronze cast to preside over his grave at his country residence, the Château de Vauvenargues.

Years later, in 1992, I interviewed my old friend Dora Maar, a talented photographer, who had witnessed and documented the making of Guernica. Picasso had told her: “I know I am going to have terrible problems with this painting, but I am determined to do it—we have to arm for the war to come.” Dora confirmed that the seemingly ironical addition of a light bulb inside the Mithraic sun in Guernica was a reference to her electrical equipment that littered Picasso’s studio on the rue des Grands Augustins in Paris.

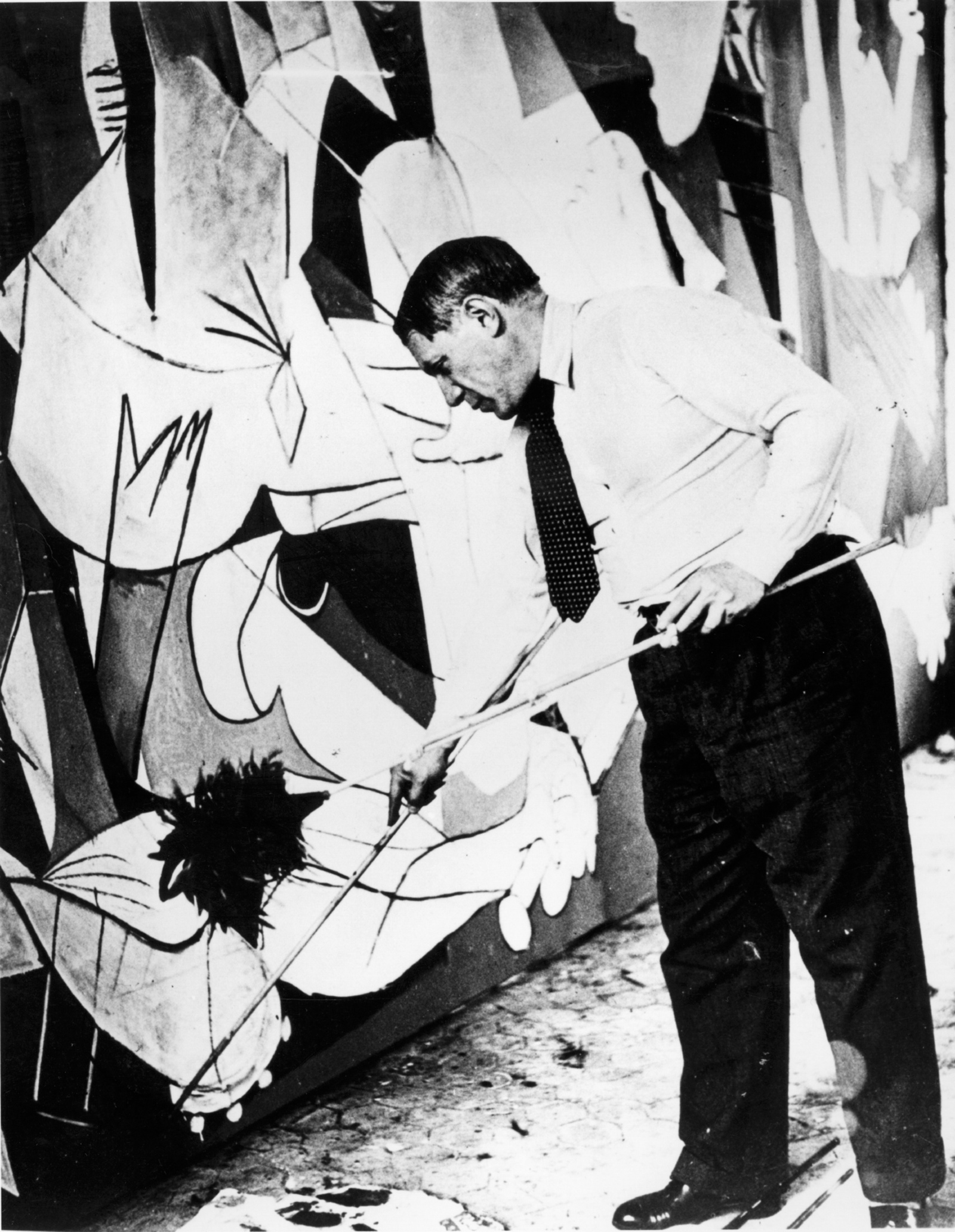

Dora’s expertise would prove immensely useful; she was able to make the first photographic record of the creation of a modern artwork from start to finish. It also helped Picasso to eschew color and give the work the black-and-white immediacy of a photograph. He did not want a shiny surface, so he asked the manufacturers of Ripolin paint whether they could develop an ultra-matte house paint. They succeeded and Guernica would be the first time it was used.

Besides making a photographic record of Guernica’s development, Dora took over when publicity people insisted on an official press photograph of the canvas. Parts were unfinished. Picasso was busy, so he had Dora do the final touches—the short vertical brushstrokes that differentiate the horse’s body and legs. The artist had told her that the dying horse in Guernica stands for pain and death—“la douleur et la mort”—and is also an allusion to the horses of the Apocalypse. The horseshoe next to the head of the dismembered soldier (bottom left) refers to the sacred crescent of Islam and Picasso’s fear of Franco’s Moroccan troops. He inveighed against the prospect of yet another Moorish occupation of Spain.

Although Dora claimed that the bull represents the people of Spain, the fact that it is based on magnificent drawings of Picasso in the role of a bearded minotaur suggests that it had a more personal significance. In the painting he portrays himself as a minotaur who coolly turns away from the carnage, seemingly unfazed by the mother figure holding a dead baby in her arms as she screams up at him. Dora referred to the table where there is a bird as a sacrificial altar. The bull and the bird are sacrificial victims.

Dora also told me that she had herself inspired the woman on fire (top right) as well as the long-legged woman in the foreground. In his memoir, the British sculptor Henry Moore describes how a group consisting of Paul Éluard, André Breton, Roland Penrose, Alberto Giacometti, Max Ernst, and himself had lunched together and called on Picasso to see what new work he had been doing:

Guernica was still a long way from being finished. It was like a cartoon just laid in black and grey, and he could have coloured it as he coloured the sketches. Anyway, you know the woman who comes running out of the little cabin on the right with one hand held in front of her? Well, Picasso told us that there was something missing there, and he went and fetched a roll of [toilet] paper and stuck it in the woman’s hand, as much to say that she’d been caught in the bathroom when the bombs came.

The artist then announced to his guests: “There, that leaves no doubt about the commonest and most primitive effect of fear.” Moore commented, “That was just like him, of course—to be tremendously moved about Spain and yet turn it aside with a joke.”

Dora photographed every major change in Guernica’s astonishingly rapid development. Her photographs of the successive states of the painting are not dated, but their order is self-evident. Picasso completed the great canvas on June 4. It had taken him thirty-five days. Dora was also in charge of the flow of visitors whom the artist was obliged to receive. Although Picasso had always discouraged strangers from watching him at work, he felt that the painting needed to be publicized for the sake of the antifascist cause. He was ready to welcome into his studio fellow artists and influential politicians, as well as other members of the European avant-garde. Guernica established Picasso as the world’s most celebrated modern artist, as beloved by the young as he was loathed by fascists, right-wing bigots, and academic hacks.

In later years Dora dismissed most of what had been written about Guernica. After breaking with Picasso, she would become a fervent born-again Catholic. She disliked discussing her feelings, except when it came to her all-important role as photographer. It was Dora’s masochistic nature that Picasso had evoked in his most harrowing studies for Guernica, and above all in the Weeping Woman series begun on May 24, before the great painting was finished.

As he later stated, Picasso could never have portrayed Dora laughing: “For me she’s the weeping woman. For years I’ve painted her in tortured forms, not through sadism, and not with pleasure, either; just obeying a vision that forced itself on me. It was a deep reality, not a superficial one.” Smeared lipstick, smudged eye makeup, tears seemingly wired to the eyes, and the soaked handkerchief clutched in her spiky finger-nailed hands capture her extreme states of agony, mental as well as physical. The Weeping Woman images emerged from Guernica. They too gave a personal form to the horrors of the Spanish civil war. In December 1937, Picasso declared: “Artists who live and work with spiritual values cannot and should not remain indifferent to a conflict in which the highest values of humanity and civilization are at stake.”

Despite Picasso’s fame, the French press virtually ignored Guernica. Even the Communist newspaper L’Humanité’s star contributor Louis Aragon failed to mention it. Only the art publisher Christian Zervos celebrated the painting in an impeccably illustrated double issue of his avant-garde magazine Cahiers d’Art. It reproduced many of the preliminary sketches and Dora’s photographs with commentaries by Michel Leiris and the Spanish poet and playwright José Bergamín, as well as a poem by Paul Éluard, “La victoire de Guernica.”

When Guernica went on display at the Exposition Internationale, the organizers at the Spanish pavilion questioned its merits. Some disapproved of its modernist style and clamored for its removal. As a result, Max Aub, cultural attaché to the Spanish embassy in Paris and a fervent backer of Picasso, felt compelled to defend Guernica:

This art may be accused of being too abstract or difficult for a pavilion like ours that wishes to be above all and before everything else a popular expression. But I am certain that with a little will, everyone will perceive the rage, the desperation, and the terrible protest that this canvas signifies.

Other Spanish officials did indeed feel that Guernica was too avant-garde for visitors to appreciate, and tried to replace it with another work commissioned for the pavilion: Horacio Ferrer de Morgado’s corny Madrid 1937 (Black Aeroplanes). This composition exploited some of the same motifs used by Picasso—air-raid victims and gutted buildings—but Morgado’s kitschy representationalism was more to the taste of the public than Picasso’s bleak monochrome modernism. The raised fists and red-scarved figures depicted by Morgado also had far more appeal to Spanish Communists. Prominently displayed, Black Aeroplanes was described to Republican leaders as “the greatest popular success” of the pavilion. Whereas Guernica, according to Le Corbusier, “saw only the backs of visitors, for they were repelled by it.”

Some Spanish modernists took against Guernica. The movie director Luis Buñuel later confessed:

I can’t stand Guernica, which I nevertheless helped to hang. Everything about it makes me uncomfortable—the grandiloquent technique as well as the way it politicizes art. Both Alberti and Bergamin share my aversion. Indeed all three of us would be delighted to blow up the painting.

Even more galling was the Basque government’s reaction. Picasso had generously offered Guernica to the Basque people but, to his fury, their president disdainfully refused. Picasso felt the Basques should be grateful to him for memorializing their ancient capital. Instead, the Basque artist Ucelay, who loathed the painting, believed the commission should have gone to a fellow Basque, and denounced Guernica:

As a work of art it’s one of the poorest things ever produced in the world. It has no sense of composition, or for that matter anything…. It’s just seven by three meters of pornography, shitting on Gernika, on Euskadi [Basque country], on everything.

As was to be expected, the Nazis reacted to Guernica with contempt. The German guide to the World’s Fair called the painting a “hodgepodge of body parts that any four-year-old could have painted.” Ironically, the opening of the Spanish pavilion in Paris roughly coincided with the opening of the “Entartete Kunst” (Degenerate Art) exhibition in Munich.

On November 1, Paris’s Exposition Internationale closed and Guernica was returned to Picasso. Eight days later, he attended the annual ceremony at the Père-Lachaise cemetery in honor of Guillaume Apollinaire (who died in 1918), who had been the closest and most influential of his poet friends. Up till then, Picasso’s magnificent model for a monument in honor of the poet had failed to find favor with Apollinaire’s widow and others who wanted a traditional memorial. Admirers from all over Europe attended the ceremony. Larrea, the Spanish director of information, recorded a dramatic confrontation between Picasso and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the founder of Futurism and “Fascist Italy’s bigwig intellectual, rather a curiosity to those hanging around him.”

Not far away, in another group of more modest appearance, stood Picasso. All of a sudden, full of himself and arrogant, the bearer of Fascist infamy approached the Spanish painter, his hands outstretched and saying for everyone to hear: “I assume that in front of Apollinaire’s tomb you won’t see any inconvenience in shaking my hand.” To which Picasso replied, “You seem to forget that we’re at war.”

After Guernica was returned to him, Picasso arranged for it to tour Scandinavia and England. It arrived in London on September 30, 1938, and was exhibited at the New Burlington Galleries where I, a fourteen-year-old schoolboy, was overwhelmed by it. A meeting with Picasso thirteen years later developed into friendship, which would inspire a biography.

This Issue

May 12, 2016

Cuba: The Big Change

James Baldwin & the Fear of a Nation

-

1

Gijs van Hensbergen, Guernica: The Biography of a Twentieth-Century Icon (Bloomsbury, 2004), pp. 32–33. ↩

-

2

“Picasso’s Broken Vow,” The New York Review, June 25, 2015. ↩