The idealistic impulse of Americans who go abroad to study other cultures or improve the lot of others more desperate than themselves makes a ripe subject for ironic fiction. Today’s expatriates who work for charitable organizations are the descendants of Henry James’s Continental travelers who sought to acquire the Old World’s culture and a maturity they found lacking in naive, materialistic America. Ever since, say, Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, the destination of these fictional pilgrims has shifted from Europe to smaller, poorer countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and the quest is similar but different: to shed one’s superficiality not only through helping the needy but also through the encounter with a different way of being, earthy, spiritual, even supernatural and animistic. Seeking the simple good life, they often find corruption and evil, which can be equally effective in overcoming innocence.

In his two novels, Mischa Berlinski has taken up such experience. His first, Fieldwork, which was praised by critics and fellow writers (from Stephen King to Hilary Mantel) and was a finalist for the National Book Award, is, among other things, an elaborate murder mystery. A young journalist-novelist is in Thailand accompanying his girlfriend, who teaches in a local elementary school; he learns about a brilliant American woman anthropologist who killed an American missionary, and goes around the countryside seeking to put together clues that will explain her crime.

He—and we—learn a good deal about trends in anthropology and about missionary work, and the various tribes, food, and sexual and religious practices in Thailand. There are ghosts and demons, whose reality the journalist-novelist narrator, named “Mischa Berlinski” (though we are assured in an afterword that the story is entirely made up), neither confirms nor denies. This first novel, written with considerable verve and invention, grounded in extensive research, is well-nigh irresistible. Hilary Mantel, reviewing it in these pages, commented:

It’s a quirky, often brilliant debut, bounced along by limitless energy, its wry tone not detracting from its thoughtfulness. You wonder what Berlinski will write next, and have faith that it will be something completely different.*

Berlinski’s second novel, Peacekeeping, is not entirely different, in that there are still idealistic, disabused expatriates, a wry tone, in-depth research about the setting (this time Haiti), a journalist-novelist narrator, an unsolved murder, and, according to the locals, supernatural forces. But this second novel differs from the first in not entirely satisfying ways. The reasons why this should be so illuminate the strengths and weaknesses of a vastly gifted author.

The story centers on two couples: Terry and Kay White, both Caucasian and from the US, and Johel and Nadia, both Haitian. Terry White is an ex-sheriff, a veteran of law enforcement, and a failed Republican office-seeker, and he is looking for a new challenge and the chance to do good. Kay is a vivacious, attractive real estate agent who went broke when the Florida housing market collapsed. They have been drawn to Haiti as a last resort. Terry is a big, handsome, beefy man who wants to be a hero, to make a difference, but he already feels himself demeaned in his supercompetent wife’s eyes after his mistaken choices, including two unsuccessful and expensive runs for state senate, and his infidelities. He has taken a decent-paying job with UNPOL, the United Nations police who are supposed to keep the peace in Haiti; but being a foreign adviser he is not allowed to make arrests, and is reduced to chauffeuring the corrupt, lazy Haitian police around, a frustrating task.

He befriends a Haitian judge, Johel Célestin, and tries to persuade him to run for office against the monstrous local boss, Sénateur Maxim Bayard. Johel, described as “a tall fat man” when we first meet him, grew up in the United States, where he was something of a child prodigy, excelled at law school, and practiced successfully in New York City before deciding to return to Haiti. Though he is eager to assert his newfound Haitian identity, the natives call him “Juge Blan” (blan meaning white) because of his soft hands, refined tastes, and intellectual air. They do not necessarily disdain him; he is simply alien in his touching desire for justice and clearly is not a product of their harsh, fight-for-survival culture. The book’s epigram, a Creole proverb that translates as “Getting by isn’t a sin,” sardonically sums up the pragmatic opportunism of the locals in Jérémie, a backwater town in Haiti.

Berlinski evokes in telling ways the clash between these two worldviews: the story told by the rich Western countries and their NGOs is that if you can just learn the facts, you can repair the infrastructure, build the roads, dig the wells, take care of the problem, naively believing, as Kay says, “Is there anybody who doesn’t want to be a good person deep down?” But the poor of rural Haiti know from experience that that is not the case:

Advertisement

The people who lived in this world did not want a set of facts. There was nothing facts could do to prevent dengue fever. Facts could not build a decent road. Facts did not give the people of Anse du Clerc a way to leave.

And so the people who lived in that world told terrible, wonderful stories—imaginative, inventive, and profound. The story the people of Anse de Clerc told to explain away misfortune was always a variant on the same theme: grievance led to hatred, hatred to magic, magic to death…. Where suffering seemed to lack an obvious cause, they invented one, and the thing that transmitted cause to effect was the supernatural. In this way of thinking, every death was a murder, every misfortune a crime—and the world made an awful, homicidal kind of sense.

But that’s the kind of story I’m telling here too.

It may seem presumptuous for the narrator to think he can appropriate this Haitian kind of storytelling; and in fact his story is not terrible, wonderful, and profound, but a rather hackneyed one involving two men in love with the same woman. Johel’s consort, the beautiful, semi-illiterate Nadia, is Haitian to the core, and seems able to cast the spell of a sorceress on the men she meets. She knows how dangerous it is to go up against the brutal sénateur, and keeps trying to dissuade Johel from running against him. “Haiti is no funny game,” she warns the expatriates. She is looking for freedom, or a green card, some way to secure her own future and escape fear, and so allows herself to be used as a sexual pawn between Terry and Johel.

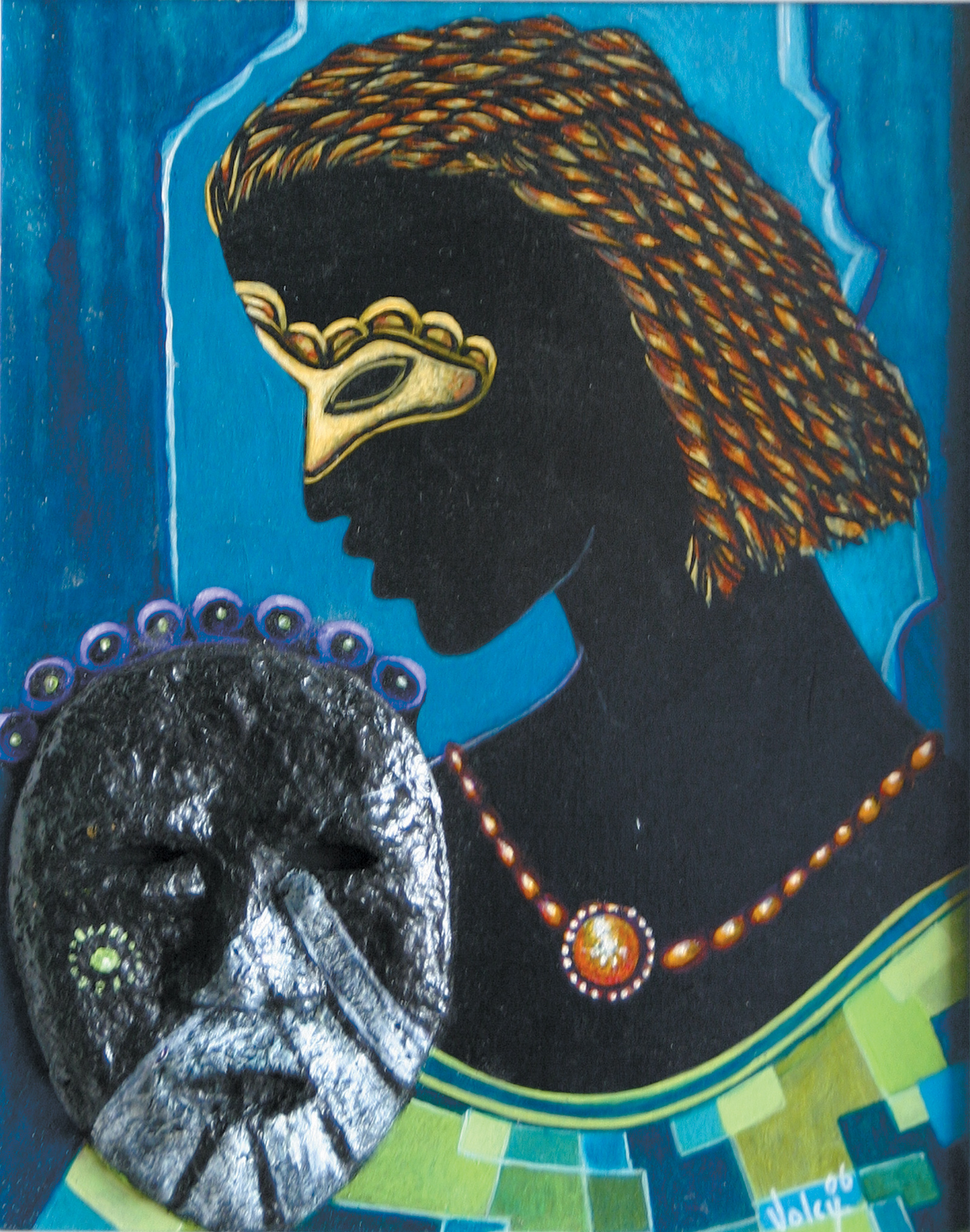

Jean Dominique Volcy/ToussaintLouvertureFoundation.org

‘Le masque,’ 2006; painting by Jean Dominique Volcy, a Brooklyn-based Haitian artist, from Save a Museum, a catalog of Haitian artwork donated to raise funds to rebuild the Musée d’Art Haïtien du Collège Saint-Pierre in Port-au-Prince, which was damaged in the 2010 earthquake. It includes an essay by Michel Philippe Lerebours and is published by the Toussaint Louverture Cultural Foundation.

Each man tries to justify his actions by asserting that it is his destiny to be in Haiti, to take risks, or to love Nadia to distraction. Berlinski plays with this theme of destiny, showing how it can be a rationalization for foolish behavior, while at the same time suggesting that without a fatalistic sense of necessity, one can be left feeling that one’s life is random and meaningless. Yet the novel never acquires the atmosphere of inevitability that we associate with Hardy, Conrad, or Greene. Instead, it sets up Berlinski’s four main characters and contrives a series of labored turns of plot in which they are caught up. When the judge does challenge the sénateur for reelection, all hell breaks loose. Friendships are betrayed, and there are rapes and beatings, election rigging, riots, a visitation of the Haitian god Ougon, shamanistic predictions, diplomatic interventions and shenanigans from Washington, and a mysterious murder that is finally solved. Invention abounds, but invention is not enough if the main characters don’t deepen, and they don’t. They remain colorless vehicles for the themes the novelist wants to demonstrate. Not that a novel can’t succeed on narrative brio alone; but at almost four hundred pages, with far too much plot and no strong characters, the book feels bloated.

Berlinski did not have this problem with his first novel because he kept the narrative moving swiftly from one minor character to another instead of staying fixed on a few principals. In addition, its narrator had a much more complex personality and was able to guide us like a skilled detective through his many encounters. But in Peacekeeping, the narrator (this time unnamed) is rarely involved in the action. He is mainly a passive recipient of the four principals’ confessions, which makes him a strategically useful foil, but not particularly interesting in himself. He passes astute judgments from time to time, such as:

What you had in the judge was one of those men who looked at all times as if he were quietly evaluating your intelligence and finding it lacking. Terry looked at all times as if he were quietly evaluating your manliness and finding it lacking. Between the two of them, they had all bases covered.

The first-person narrator thus comes across as an observer, temporarily willing to acknowledge the qualities of this or that person, while underneath, we sense, feeling superior to all. Perhaps that’s why the strongest moments in the novel occur when the narrator is digressing from his main characters, explaining the way official promises remain unfulfilled in Haiti, or the ways international aid functions:

Advertisement

All along the road, every couple hundred meters, there were big hand-painted signs explaining in French that this was the site of some international development project. A project outside Gommier to help farmers affected by hurricanes, paid for by the government of Japan and executed by the World Food Program. A pilot project to protect the banks of the Roseaux River, paid for by the European Union. The construction of a national school in Chardonette, paid for by the European Union. UNESCO was rebuilding the Adventist college Toussaint Louverture.

In a large open field, the Inter-American Development Bank was proposing to build sixty latrines. The project had been scheduled to begin four years back and would last four months, but the field was still barren and rocky when Terry drove by. USAID began a hillside agricultural program: nowadays the hill was nothing but rocks and stones. The IADB was rehabilitating the water supply of Carrefour Charles. There was a program to encourage the production of yams, paid for by the United Nations Development Program. A faded sign, almost falling down: CARE was putting in place a program designed to guarantee food security.

Good intentions, from the largest to the smallest, are diverted:

When he [a Quebecer named Eric] went home on leave, he organized a toy drive, his whole community pitching in to buy a couple hundred stuffed animals. That’s how all those little bears and otters and ocelots could be found on sale in the marché, right next to the mosquito nets distributed to the poor by the WHO.

Berlinski is a highly skilled novelist: he can shift points of view seamlessly from one character’s interior monologue to another, then back to the narrator. He finely describes market food, local color, landscape, weather, articles of clothing. He smoothly brings research into the story, and digresses to the larger socioeconomic picture. His pithy aphorisms encapsulate the differences among people from different countries, for example when they meet at large parties. He can shift from the poetic to the mundane, and from realism to a more mythical plane. In short, he is in command of the techniques of the contemporary novel.

He is not afraid to show his storytelling hand by addressing the reader: “Start with this. Terry had this thing he did, walking around cemeteries. Some people don’t know the dead can talk. That’s their secret. But someone’s got to be listening.” Does the author believe the dead can talk? Berlinski remains elusive about the subject. His prose varies from short staccato sentences to longer, syntactically complex ones, and from literary to journalistic to the tone of pulpy commercial fiction. All in the name of storytelling. He defends his method at one point:

The highbrows may snoot, as they will, but by my lights, a good story is the greatest of all literary inventions, the only realm in our existence where for every “Why?” there exists a commensurate “Because…” Those two words, “why?” and “because,” might be the best thing our species has going for it.

Such metastatements suggest Berlinski’s ambition, his sense of literary mission. He writes of the English novel’s “massive vocabulary and remarkable ability to leapfrog effortlessly between the lyric and the vulgar, the raw and the fucking sublime.” There are times when he seems too insistent on vulgarity, as when Johel is daunted by a large turd that won’t flush, or Terry exclaims:

Haiti is a lot like pussy…. It’s hot and it’s wet and it smells funny. You didn’t know about pussy, somebody told you about pussy, you wouldn’t think you’d like it much. Probably think it was something nasty. But you get to know pussy, you can’t stop thinking about it ever.

Perhaps we are meant to read that as an attempt to put this character in a bad light, but still there seems to be a basic confusion on the author’s part between crudity and vitality, the sensationalistic and the earthy or gritty.

As a second novel, Peacekeeping does seem a little sourer than Fieldwork. Perhaps Berlinski could not bring himself to feel as enchanted with Haiti as he had been with Thailand. At the end of Fieldwork the narrator stays behind in Thailand, while his girlfriend returns to America. The expatriates in Peacekeeping all leave Haiti and return to their home ground (except for the one whose corpse is left behind). The experiment conducted by this very gifted writer is over, the disillusionment complete.

-

*

See “The Fate of a Demon,” The New York Review, July 19, 2007. ↩