There has never been a painter quite like Jheronimus van Aken, the Flemish master who signed his works as Jheronimus Bosch. His imagination ranged from a place beyond the spheres of Heaven to the uttermost depths of Hell, but for many of his earliest admirers the most striking aspect of his art was what they described as its “truth to nature.” The five hundredth anniversary of his death in 1516 has inspired two comprehensive exhibitions, at the Noordbrabants Museum in his hometown of ’s-Hertogenbosch and at Madrid’s Museo Nacional del Prado, as well as an ambitious project to analyze all of his surviving work, drawn, painted, and printed, according to the latest scientific techniques (the Bosch Research and Conservation Project). Yet despite all we have learned through these undertakings—and it is a great deal—the man his neighbors knew as “Joen the painter” remains as mysterious as ever.

How could it be otherwise with so strange and masterful an artist? His early admirers celebrated the boundless ingenuity of his work, but they also recognized the sureness of his hand and his unerringly observant eye. In the precision of his draftsmanship, his sensitivity to landscape, his fascination with animals, he shows some surprising affinities with his contemporary from Florence, Leonardo da Vinci—who else but Leonardo would have noticed, and recorded, as Bosch does, the way that evening light can turn the waters of a distant river into a radiant mirror? Both artists were fascinated by grotesque human faces, but Bosch also detailed grotesque human behavior with a bawdy abandon all his own. No matter how closely we look at his minutely particular works, there is always something more to see.

The earthly life of Jheronimus van Aken is sparsely documented; the clues to his inner life are fewer still. He grew up on the northernmost border of the Flemish-speaking, Burgundian-ruled Duchy of Brabant, in a city whose name means “the duke’s forest”: Silva Ducis in Latin, s’-Hertogenbosch in Flemish, Bois-le-Duc in French, Herzogenbusch in German, Bolduque in Spanish—all languages in common use in his times and in his region. The forest itself was probably an ancient memory by the time of his birth around 1450, replaced by an emporium that ranked only behind Brussels and Antwerp for size and importance within its area, famous for its steel knives and its cloth market.

The van Aken family had been painters for at least three generations, and residents of Den Bosch (the colloquial name of s’-Hertogenbosch) for two. In 1430, three years or so after arriving in the city, Bosch’s grandfather and grandmother enrolled as members of the Brotherhood of Our Lady, the local religious confraternity. Ever afterward, the brotherhood would provide their large extended family with spiritual solace, social contact, and artistic commissions. Their four sons, Thomas, Jan, Goessen, and Anthonius, would become painters in their own right, as, in turn, would the three sons of Anthonius van Aken: Jan, Goessen, and Joen/Jheronimus. All of them seem to have had active careers. Only one had a truly exceptional talent.

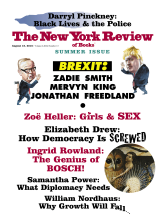

This Issue

August 18, 2016

Fences: A Brexit Diary

Black Lives and the Police