We were sitting, my wife and I, at a summer dinner party by the pool, in honor of a mother and her college-age daughter visiting from Chicago. Just for a moment, as night was coming on, the subject of rattlesnakes—our Massachusetts Timber Rattlesnakes, Crotalus horridus, to be precise—edged out the incessant talk of Trump Trump Trump. Our visitors, full of the police troubles in Chicago, were unaware of the Great Rattlesnake Controversy, and Tara, our well-informed hostess, weighed in first.

Four towns in central Massachusetts, she explained, were deliberately flooded during the 1930s, their entire population—along with 6,000 graves, she added ghoulishly—“relocated” to create the Quabbin Reservoir, and bring water to Boston. Some quaint houses were salvaged from the general destruction and moved, wall by wall, to prosperous towns like Amherst (where we now live), but stores and other businesses, a state highway, even a railroad, were lost forever.

As two huge dams were set in place and the waters rose, eventually covering thirty-nine square miles, some of the higher elevations—like Mount Ararat after Noah’s flood—became islands in the vast expanse. One of these islands, closed to public access and located in the middle of the reservoir, is named Mount Zion, and it was here that the state of Massachusetts has proposed to introduce a small colony of Timber Rattlesnakes, beginning in 2017, to the vehement outrage of many local residents, who treasure the banks of the Quabbin for fishing and its pristine waters for boating.

Tara is a local, unlike the rest of us urban transplants, and I respected her sense of solidarity with the displaced. Their parents and grandparents were not asked if they were okay with abandoning their homes; they themselves were not asked if they wouldn’t mind having a few rattlesnakes as neighbors. But I myself would not have begun the story with the eradication of the four towns by government fiat, and the scattering of their population.

I would have begun, instead—I actually did begin, and rather vehemently, to the evident surprise of our Chicago contingent—with the indiscriminate slaughter of native rattlesnakes, which began much earlier, intensified with the rapid settling of New England by Europeans schooled in the biblical evils of the serpent, the devil incarnate, and continues unabated to this day, even though it is a serious crime to kill or even to disturb a rattlesnake, an officially endangered species in our state.

Never mind that rattlesnakes are not particularly dangerous—unless you’re a mouse, I added wittily. They rarely bite people; their venom is seldom lethal and anti-venoms are widely available and effective. Nor are they quick to anger. The Timber Rattlesnake is a mild snake, I insisted, shy and nervous of humans.

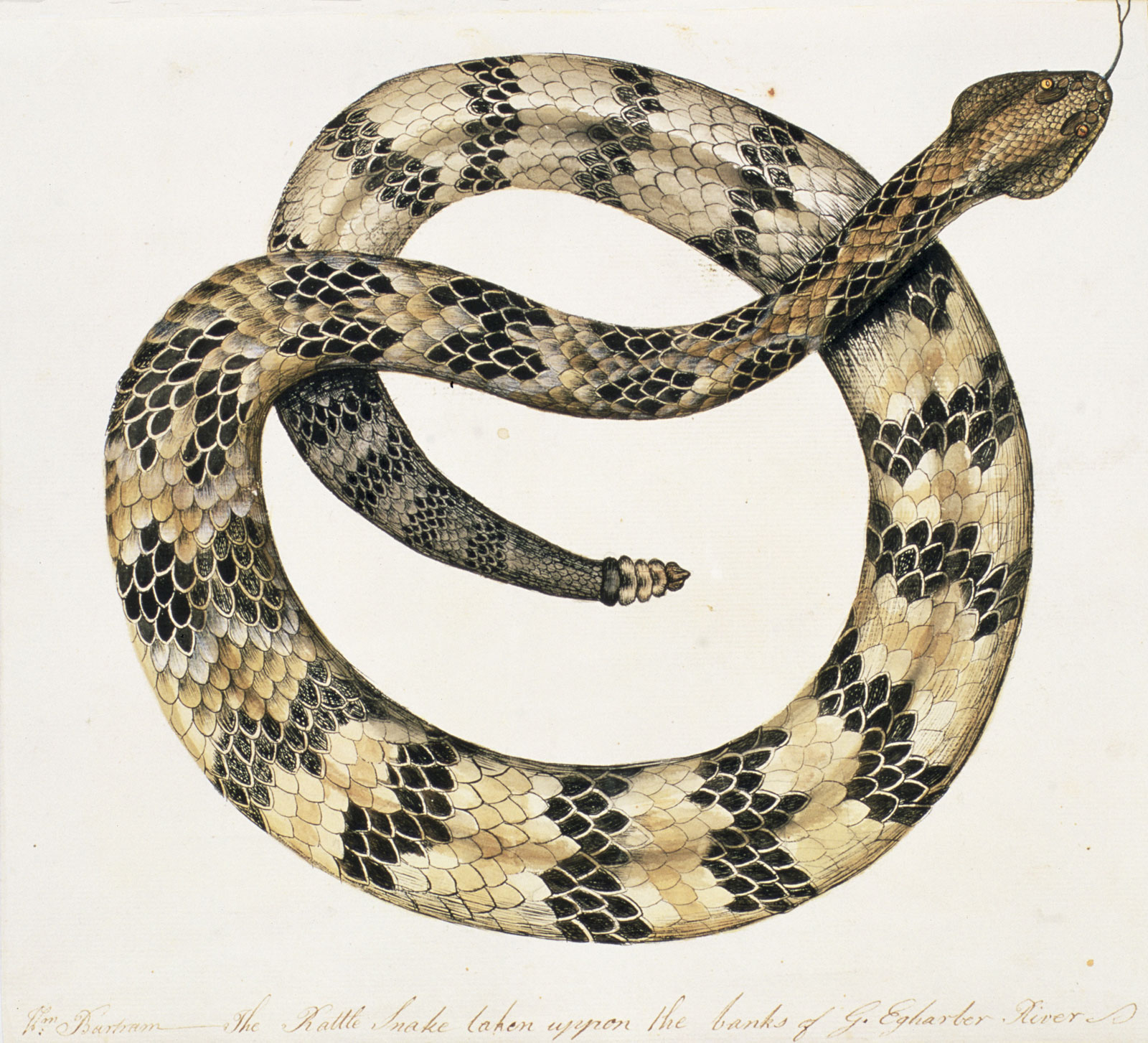

As the Quaker naturalist William Bartram (one of my heroes, and much admired by Coleridge) explained during the 1770s, the rattlesnake “is never known to strike until he is first assaulted or fears himself in danger, and even then always gives the earliest warning by the rattles at the extremity of the tail.” It is a sad irony that the snake’s rattle, which functions as a warning device, is widely regarded as a bellicose drumroll, or war-cry, instead. It may well have been in a mood of remorse for having killed a rattlesnake on impulse that Bartram, vowing solemnly that he “would never again be accessory to the death of a rattle snake,” painted his marvelous portrait of a coiled rattler.

The last time someone actually died of a rattlesnake bite in Massachusetts was in 1791, and yet the emblematic idea of the snake, lurking in the underbrush, can’t quite be shaken. “Though in many of its aspects this visible world seems formed in love,” as Melville wrote in his chapter on the whiteness of the whale, “the invisible spheres were formed in fright.” During the nineteenth century, rattlesnakes, along with wolves, were often identified with American Indians, those other sinister denizens of the New England forest, and all three suffered the same fate. The popular Southern novelist William Gilmore Simms, whose books are larded with the snakelike characteristics of the native population, believed that rattlesnakes were among the weapons of American Indians: “with a single note, he bids the serpent uncoil from his purpose, and wind unharmingly away from the bosom of his victim.”

Timber Rattlesnakes, nostalgically recorded in local place names like Rattlesnake Gutter (where the plumber who snakes our drains has his business) and Rattlesnake Knob, once thrived in New England. Not anymore. They have been wholly exterminated in Maine and Rhode Island, and it is estimated that not more than two hundred survive in a few disparate colonies—just five, two of which are in immediate jeopardy—in Massachusetts.

Advertisement

Under the circumstances, it seemed reasonable to conservationists and herpetologists to find an uninhabited island, outfitted with the belowground dens essential to snake survival in the winter, and slowly introduce a small colony of rattlesnakes, one by one, equipped with monitors to track their location. Mount Zion is large enough, at 1,350 acres, that snakes, according to experts, “would have little motivation to leave.” If, by chance, a rattler rashly swam to the mainland—and scare-videos showing rattlesnakes swimming were widely circulated among opponents of the scheme, and duly sent to legislators—it could not long survive there without its den, even if unmolested by humans.

“This dreaded animal is easily killed,” Bartram noted; “a stick no thicker than a man’s thumb is sufficient to kill the largest at one stroke.” Against a car, a slow-moving snake doesn’t stand a chance. “The whole point of this project,” as Tom French, assistant director of the State Division of Fisheries and Wildlife’s Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, who developed the Zion Island plan, told The New York Times, “was to find a place we could protect rattlesnakes from people.”

The Zion Island plan may have seemed reasonable to conservationists, and even to Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker, a moderate Republican, and thus something of an endangered species himself. “I can’t believe here I am, defending snakes,” Baker told a Boston Herald radio program. “I don’t like snakes either, OK? I’m not a snake guy. But they absolutely have a role to play in nature.”

It did not seem reasonable to the locals. “All it takes is two of ’em to get across,” Kyle Whitcomb, a police officer and avid fisherman in Ware, which borders the reservoir, told The Boston Globe, “and then all of a sudden you got snakes all throughout the town of Ware.” He added, “I’m petrified of snakes.” According to another local quoted in the Times, “Instead of ‘Snakes on a Plane,’ it’d be snakes on an island.”

As the night deepened, and mosquitoes (Zika!) swarmed around the outdoor candles, I found myself, a little drunkenly, venturing a possible relation between the growing xenophobia in our country and the senseless demonizing of the rattlesnake. “Here’s the government,” I imagined the anti-snake crowd saying, “trying to let in a bunch of snakes, from out of state, no less, and actually hoping they will thrive here. Put up a wall instead; make ’em pay for it; keep ’em out!”

In an interesting scholarly article called “Rattlesnakes in the Garden,” Zachary Hutchins notes that during the struggle for independence the rattlesnake became a symbol (“Don’t tread on me!”) of “white colonial unity” against the British oppressor. “Popular rhetoric after the American Revolution,” however, “used the rattlesnake and serpentine fascination as metaphors for a wide variety of subversive forces that threatened the nation, especially the dangers associated with racial diversity and religious declension.” By such strange cycles, the unifying emblem seamlessly morphs into the exclusionary nightmare.

For the moment, the wall-builders, at least as far as rattlesnakes are concerned, appear to be in the ascendant. The Zion Island plan has been shelved for the moment, “on pause,” according to Governor Baker, pending more discussion and analysis. An exasperated conservationist named Lou Perrotti, who is supervising the breeding of Timber Rattlesnakes at a zoo in Rhode Island for eventual (or, let’s say, possible) release on Zion Island, put the problem memorably. “If we only conserve the cute and the cuddly,” he said, “we’re going to have forests full of butterflies and bunny rabbits, and they’re going to be very nonfunctioning ecosystems that would eventually collapse.”