Day and night,

I copy the Diamond Sutra

of Prajnaparamita.

My writing looks more and more square.

It proves that I have not gone entirely

insane, but the tree I drew

hasn’t grown a leaf.

—from “I Copy the Scriptures,” in Empty Chairs

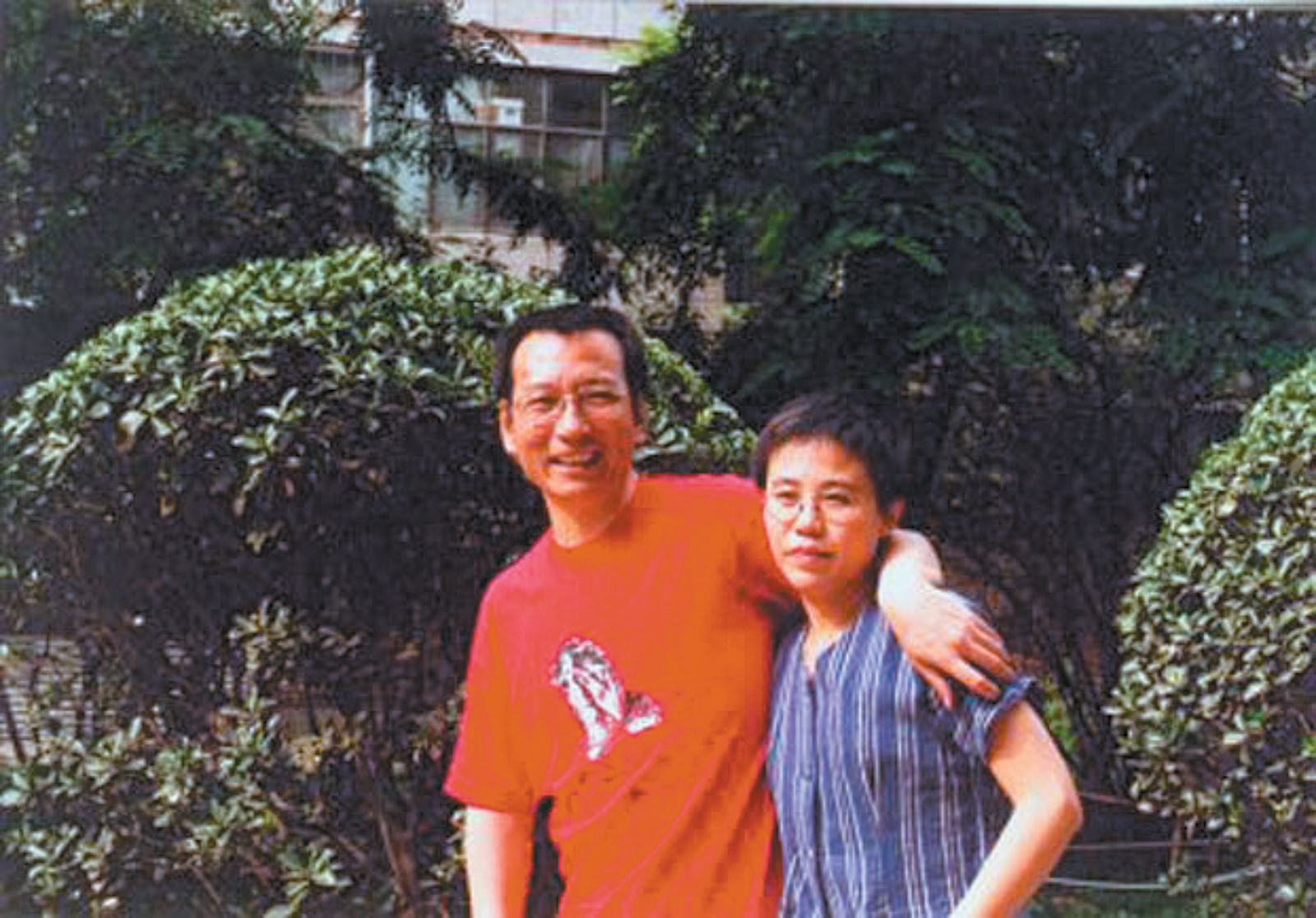

Every month, the Chinese poet, photographer, and artist Liu Xia boards a train bound for the country’s north. Carrying food and books and escorted by four plainclothes police officers, she heads for a prison in the city of Jinzhou where her husband, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo, is serving a sentence for subversion of state power. The ritual rarely varies: rising early to get the morning train, a short visit, and the train back.

The ride used to take six hours each way but Ms. Liu now makes it in just three—a tribute to the power and might of a state that rolls out high-speed rail lines as quickly as it snaps up those who oppose its vision of China’s future. Now fifty-five years old, Ms. Liu is one of those victims: a small, fragile woman with extremely short-cropped hair that sets off her high cheek bones and bright, wide eyes.

She has lived under strict police surveillance ever since her husband won his prize in 2010, one year into his eleven-year prison term. For more than three years, she could not see friends or even receive phone calls. Those close to her spoke of her becoming unbalanced from the pressure. When Associated Press journalists snuck past guards and knocked on her door in 2012, she trembled, cried, and said her situation was “Kafkaesque.” In 2014, people close to her reported that she was hospitalized due to heart ailments and depression.

Now friends say that she is regaining strength and devoting herself to reading and writing. While her husband is most famous for his blunt, sarcastic, and highly topical essays, Ms. Liu’s works have taken longer to become known—not surprising for an artist who cannot publish or exhibit in her home country. But her poems and artworks are emerging in their own right as major statements about life under authoritarianism and reaching a more global audience thanks to a newly translated volume of her poetry and a biography of her husband that includes large sections on her own life. In addition, new translations of Liu Xiaobo’s poetry show the central part that his wife has played over the past two decades.

Some of his poems are collected in June Fourth Elegies, a book mainly devoted to those honoring the victims of the Tiananmen Square massacre of June 4, 1989. The last section of the book, however, includes five poems to Liu Xia, many of them written during an earlier time in prison, such as “Greed’s Prisoner”:

Beloved

my wife

in this dust-weary world of

so much depravity

why do you

choose me alone to endure

Reading Liu Xia’s poems, there’s no doubt that she has had much to endure. Some of the poems in Empty Chairs deal with her mother-in-law, who monopolized visits to her son in the 1990s. In a 1997 poem, “A Mother,” Liu Xia writes of how “only by hating me/can she show her aging love for her son.”

Since then, of course, the price Liu Xia pays has been steeper than a tense family life. She is under twenty-four-hour police surveillance, only allowed to visit a circumscribed group of friends, and always with police accompaniment. She gets one hour a month with her husband, and is only allowed to see him through glass and to talk through a telephone receiver. Her brother was sentenced to eleven years in prison on grounds of vague “economic crimes,” a blow to her family that she writes about in a poem called “Snow.” Even her own ability to create art seems damaged by her relationship to Liu Xiaobo; in an untitled poem from 2009, she writes of her husband’s blindness to it:

You love your wife and are proud she stays with you

through the darkness; you let her do what she wants, write for you

even after death, but in her verses there are no sounds. None.

And yet her poetry is not obsessively about their relationship—and indeed many of her poems were written before they married. Of those written later, many can be read biographically, but they also speak more broadly about worry, waiting, and longing.

Most striking are three images that must count as some of the most powerful symbols of the long struggle by Chinese dissidents for rights: birds, trees, and chairs. The empty chair has of course come to symbolize Liu Xiaobo—a chair was left empty for him at the Nobel awards ceremony and for a short while in China it became a symbol on the Internet for a man whose name is banned in China. Liu Xia had created this image for her missing husband as far back as his 1990s prison stay. In the 1997 poem “Shadow,” dedicated “for Xiaobo,” she uses all three metaphors to describe her sense of loss—not only her missing husband, but the missing years from her life:

Advertisement

A chair and a pipe

wait for you in vain.

No one sees you walking down the street.

In your eyes, a bird is flying,

green fruit hangs from a tree without leaves—

since that morning, the fruit refuses

to ripen in the fall.

In earlier poems, the bird is more mysterious—a specter that comes and goes, almost as if inspiring her. In a 1983 poem, “One Bird Then Another,” when she was still married to another man, she wrote:

Back then,

we were always talking

about the bird. Not knowing

where it came from—the bird,

the bird—it brought us

warmth and laughter.

In his introduction to Empty Chairs, the exiled writer Liao Yiwu writes that the bird once referred to a giggly, slightly manic Liu Xia. She was such an inspiring poet that even back in 1982 an aspiring writer like Liao would make a three-day journey from Sichuan to Beijing to seek her out. He writes of visiting her home in Beijing, which was already a popular salon for freethinkers:

The bird called Liu Xia lived in a large cage-like room on the twenty-second floor of a building on West Double Elm Tree Lane in Beijing. I traveled from Sichuan to meet her and climbed up the stairs as the elevator was broken. From the moment I knocked on the cage door, Liu Xia never stopped giggling. Her chin became pointy when she smiled, and she laughed like a bird, unrestrained…. Talking, we giggled for no good reason. Tears fell while we were still laughing.

The two became close friends, with Liu Xia able to drink so much that Liao called her his “drinking master.” After she met Liu Xiaobo in the 1980s, her ability to drink drove her nondrinking husband slightly crazy, and Liao recalls how Liu Xia would make her husband pour her wine as if he were her servant.

Once they started living together in the early 1990s, Liu Xia and Liu Xiaobo became inseparable. Her importance in his life is discussed in detail in Steel Gate to Freedom, the exiled writer Yu Jie’s biography of Liu Xiaobo. Yu, a prominent Christian and best-selling essayist who now lives in Washington,* spent years collecting information on the couple before he left China. It is the only full-length biography of Liu, portraying him as a complex figure—devoted to political reform, idealistic, and unremittingly self-critical, but also promiscuous, callous toward his first wife, and reckless. What becomes clear in reading it is that Liu Xiaobo’s maturation came largely from his relationship with Liu Xia.

In these colorful and closely reported chapters, we see the daily rituals that held their lives together. One was eating—the two seemed to have insatiable appetites, driving around Beijing to their favorite Sichuan and Huaiyang restaurants. Yu describes their favorite dishes, which they washed down with wine (Liu Xia) and Coke (Liu Xiaobo). Liu Xia was also a great cook and would scour Beijing’s foreign grocery stores for hard-to-find ingredients for feasts she would cook at home for their friends.

They had met in the 1980s but became close only after Tiananmen. In 1995, Liu Xiaobo was detained for writing an open letter calling for basic rights and then formally sentenced in 1996 to three years in prison. Liu Xia traveled regularly up to the labor camp and—in a phrase that is now legendary—told the guards that “I want to marry that enemy of the state!” Eventually she did, while he was still in prison; their wedding banquet was in the prison cafeteria.

Back in Beijing, she wrote him a postcard every day of his prison term expressing her love. Because she could not mail the cards, she stuck them on the walls, so when he came home he found more than a thousand plastered around the apartment.

The couple had only nine years together as husband and wife. In 2008, hundreds of leading intellectuals signed a document called Charter 08, which set out to emulate Charter 77, a loose association of people in Czechoslovakia who, defying the imposed Soviet system, made a public case for basic civil rights. The Chinese document (published in these pages on January 15, 2009) called for freedom, human rights, equality, republicanism, democracy, and constitutional rule. More than 350 people initially signed the document, many because of Liu Xiaobo’s involvement as one of its authors. His support gave it credibility and made it widely known.

Advertisement

For Liu Xia, none of this was of direct interest. More of an anarchist than a democrat, she rarely read what he wrote. Yu quotes her as saying: “But when you live with someone like that, even if you don’t care about politics, politics cares about you.” Her political instincts, though, were accurate after he was arrested. Many friends forecast a speedy release, but Liu Xia predicted ten years. She was only one year off.

Despite her sense of humor, the pressure has been enormous. Yu writes that she suffered from hormone imbalances, skin rashes, chronic insomnia, and relied on pills or wine to get through the night: “Two prisoners, one in a visible cell, the other in an invisible one.”

During all this tumult, her poetry remained precise, focused, and grounded in the interiority of daily life—very different from the large-scale ideas of her husband, or the lofty “Misty” poetry popular in China and abroad in the 1980s. A perceptive afterword to Empty Chairs by the translators Ming Di and Jennifer Stern helps us understand Liu Xia’s place in the sometimes confusing world of Chinese poetry and literature. As they note, Liu Xia was a fan of Sylvia Plath but unlike many Chinese poets did not write confessional poetry; instead, her poems are inspired by novels, and often tell stories or recreate folktales.

Even in her later poems, trees and birds dominate. The last poem in the book, from December 12, 2013, is “How It Stands”:

Is it a tree?

It’s me, alone.

Is it a winter tree?

It is always like this, all year round….

Aren’t you tired of being a tree your whole life?

Even when exhausted, I want to stand.

Is there anyone to keep you company?

There are birds.

I don’t see any.

Listen to the sound of fluttering wings.

Wouldn’t it look nice to draw birds in the tree?

I’m so old and blind I wouldn’t see them.

You don’t know how to draw a bird, do you?

You’re right. I don’t know how.

You’re an old, foolish tree.

I am.

Reading those lines, the exiled Liao Yiwu urges her to become a bird again, and fly—to somehow escape China like he did when he walked across China’s southern border to freedom. But he knows she can’t:

She can’t move her own nest—Liu Xiaobo can’t move, so she can’t either. She’s turned from a bird into a tree, her feathers becoming white and withered. But as a tree she still sings the songs of birds.

This Issue

September 29, 2016

Maya Lin’s Genius

The Heights of Charm

How They Wrestled with the New

-

*

See my “China’s ‘Fault Lines’: Yu Jie On His New Biography of Liu Xiaobo,” NYR Daily, July 14, 2012. ↩