1.

In 1977, a bored Republican lawyer from Louisville named Mitch McConnell, then thirty-five, decided the time had come to act on a lifelong dream to become somebody important—in this case, county judge of Jefferson County, Kentucky, which surrounded the city of Louisville. “Judge” was the archaic title for the county’s chief executive. The last Republican to hold the job had become Senator Marlow Cook, a figure on the national stage, precisely what McConnell dreamed of becoming. He had been running for office since high school, winning nearly every contest he entered. Now he hoped this could be his own first step toward a seat in the United States Senate.

In his new memoir McConnell writes poignantly about that first campaign: “Approaching strangers, speaking in front of crowds—it was all extremely hard for me at the time…. At my core, I’m quite shy.” He and an old friend who helped manage the campaign

slogged through the summer, spending our weekends eating fish sandwiches and shaking hands at the Catholic picnics popular throughout the county. During the week…I’d travel up and down Dixie and Preston Highways as the sun went down, going in and out of stores by myself, introducing myself to the employees and customers at local diners and small businesses, and explaining why I was running for county judge. County government was a mess. People were escaping from the jail. Taxes were going up.

He was able to raise enough money, McConnell writes, to put ads for his campaign on radio and television. In November, he defeated the incumbent Democrat by six percentage points, to his great satisfaction.

McConnell’s charming account of that first experience in electoral politics has but one flaw: it isn’t what happened. Alec MacGillis, a fine reporter who has worked at The Washington Post, The New Republic, and ProPublica, fills in some large holes in McConnell’s account in his short but revelatory book, The Cynic: The Political Education of Mitch McConnell. First and most important, the substance of McConnell’s campaign was shaped not by the candidate and his sidekick with whom he ate fish sandwiches, but by two highly experienced (and expensive) campaign consultants. McConnell’s campaign in 1977 cost $355,000, a level of spending without precedent in Jefferson County. His success raising money allowed McConnell to hire Robert Goodman, an artful producer of campaign commercials for television, and Tully Plesser, a prominent pollster and strategist.

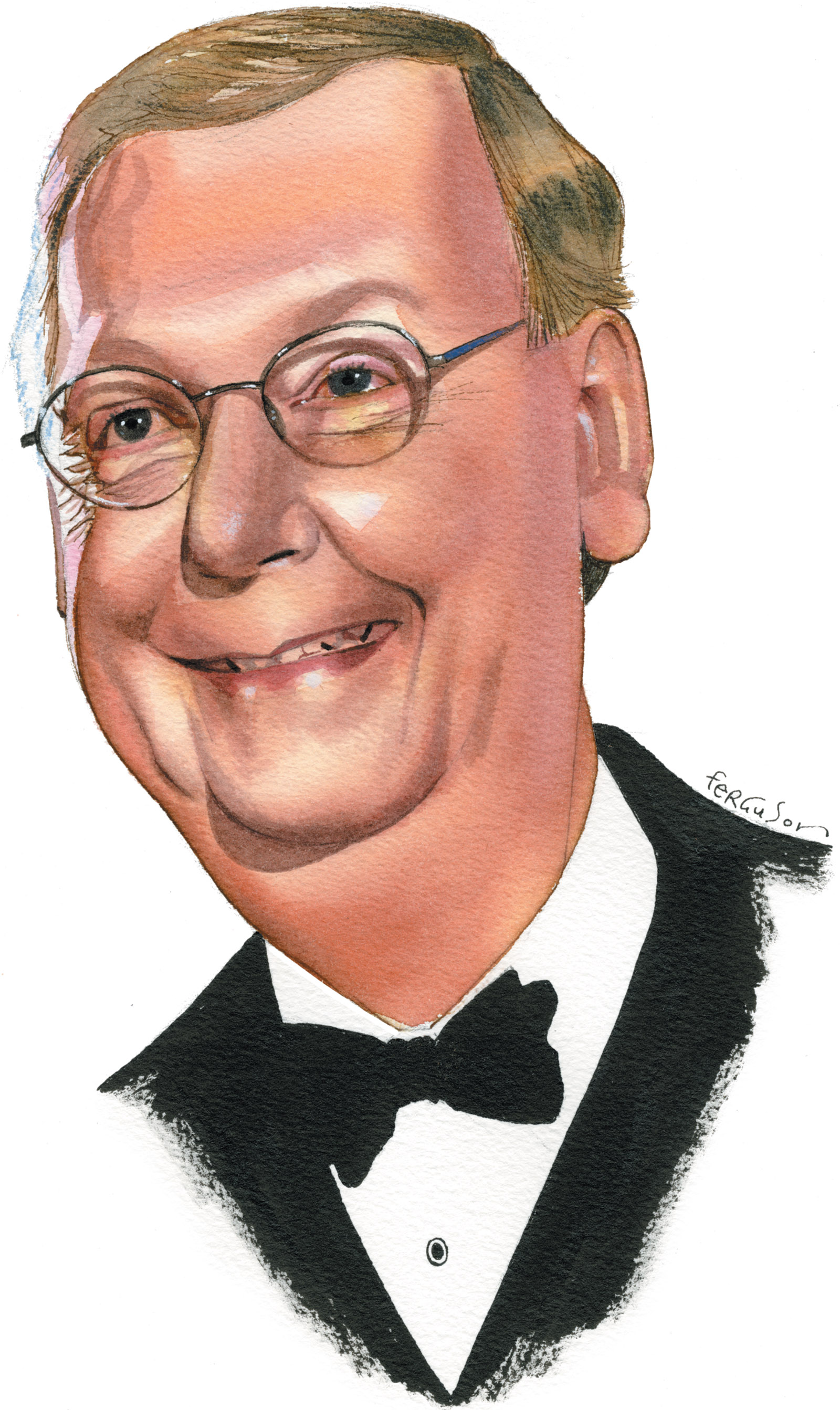

MacGillis tracked down both Goodman and Plesser nearly four decades later. This was worth the effort. Both men remembered being underwhelmed by their new client in Louisville. McConnell wasn’t an interesting person, Goodman told MacGillis; he had no “aura” to exploit, and “he wasn’t like a man’s man, really.” Plesser added that McConnell “doesn’t make a dominant physical presentation.” (Today, at seventy-four, he still doesn’t.)

But then these two old hands discovered a less obvious trait in their client that more than compensated for his dearth of God-given political appeal. McConnell was prepared, even eager, to do whatever was necessary to win the election. Neither had ever had such a malleable client. “He was very easy to deal with,” in Goodman’s words. “Mitch was the best client,” Plesser added. “He really listened, he didn’t argue…. We were absolutely starting from scratch. We could build something [that is, a candidate] just the way we wanted, with no pushback.”

McConnell accepted the consultants’ suggestion that he approach his electorate as segments of voters with particular, often narrow interests, all identified by Plesser’s polling. They suggested that he “create not just a message for each but, essentially, an image of himself for each,” in MacGillis’s words.

This was easy because McConnell wasn’t known for anything. At the time he considered himself a Republican in the mold of Cook and John Sherman Cooper, both of whom he had worked for in Washington. Both were moderate-to-liberal Republicans, a type now nearly extinct. McConnell was then pro-choice. In the course of that campaign he announced his support for allowing Jefferson County’s public employees to bargain collectively, a position that won him the endorsement of the local AFL–CIO. (Once elected, he ignored this idea. Later he described his campaign pledge as “open pandering” to the unions, which were strong in Louisville.) He was also endorsed by the most important liberal institution in Louisville, The Courier-Journal. (“The biggest mistake we ever made,” the paper’s publisher said years later.)

Goodman and Plesser were practitioners of the dark arts that had begun to take over America’s political campaigns. Consultants and pollsters play on voters’ emotions; they can create “issues” out of whole cloth—or, more accurately, using polling results that can reveal what messages may sway selected voters. Goodman produced a TV spot for that campaign that is still remembered in Louisville, featuring a farmer raking manure out of a horse’s stall and comparing what he was raking to statements by McConnell’s opponent, the incumbent county judge. McConnell had nothing to do with creating this “message,” but it suited him fine. “Oh, God, he loved it,” Goodman told MacGillis.

Advertisement

2.

Why was McConnell so eager to run and win an election? His answer to that question may be the frankest passage in his book:

The truth is that very few of us expect to be at the center of world-changing events when we first file for office, and personal ambition usually has a lot more to do with it than most of us are willing to admit. That was certainly true for me, and I never saw the point in pretending otherwise.

He quickly adds that this “doesn’t mean we don’t bring deep and abiding concerns to the job,” but in this full-sized political memoir, we learn almost nothing about McConnell’s concerns about ideas or principles or substantive political issues. Nor does his career in the Senate suggest he has ever had them. His name is associated with just one piece of significant legislation, the 2002 act known as “McCain-Feingold” for the two senators who sponsored it, the Arizona Republican John McCain and the Wisconsin Democrat Russ Feingold. McConnell won notoriety for his fierce opposition to this bill, which banned the use of “soft money” from political campaigns—i.e., contributions from a variety of sources not to candidates but to political parties with no limits on the use—a major goal of campaign finance reformers. When the bill was passed despite McConnell’s fierce efforts, he filed an unusual suit in federal court to block the work of his Senate colleagues as an unconstitutional restriction on “freedom of speech.” McConnell v. Federal Election Commission reached the Supreme Court, which upheld McCain-Feingold.

That McConnell became a prominent public figure because of his battles against limits on campaign spending is entirely apt. His career spans the era in which money has become the dominant force in our elections, and this suits him fine. Money is the most important ingredient in winning elections, McConnell decided after that first victory in Jefferson County. “Everything else is in second place,” he said in a post-election interview. He promised that in future campaigns, “I will always be well financed, and I’ll be well financed early.” He has kept that promise.

Ironically, MacGillis reports, the first time McConnell publicly addressed the campaign finance issue he cast himself as a reformer. This was in 1973, the year the Watergate scandal blossomed. McConnell was then chairman of the Jefferson County Republican Party, and he seemed to realize that Watergate was a problem for his party. He wrote an Op-Ed piece for The Courier-Journal proposing radical campaign finance reforms, including a $300 limit on contributions to candidates in state races and full disclosure of all contributions of any size. He wrote favorably about public financing of campaigns for governor and president. Without such reforms, he wrote,

many qualified and ethical persons are either totally priced out of the election marketplace or will not submit themselves to questionable, or downright illicit, [fund-raising] practices that may accompany the current electoral process.

Was he serious? Well, no. McConnell said in an interview years later that these recommendations were political posturing, “playing for headlines” to distract voters from Watergate. He developed his anti-reform views when he taught a course on campaigning and decided that restricting contributions and spending abridged freedom of speech and could not be permitted.

3.

McConnell writes candidly about how his own career depended on unfettered access to campaign cash: “I never would have been able to win my [first run for the Senate in 1984] if there had been a limit on the amount of money I could raise and spend.” His rationale here is telling:

The only way a guy like me had a chance—a guy with no real political connections [after six years running the state’s largest county] and no money [in fact he was a champion fund-raiser], no strong political apparatus to rely on, holding views opposed by the mainstream media and organized political groups like the labor unions—was to get around the inherent advantages of the liberal majority party [four years into the Reagan presidency] by raising enough money to take my message directly to voters.

Whatever the honesty or intellectual merit of this analysis, the implicit advice he was giving to himself was sound, and he took it to heart in 1984 when he challenged Walter (“Dee”) Huddleston, a two-term incumbent in the Senate. McConnell raised nearly $1.8 million, a large amount for a Senate race in those days. He traded up for a fancier, and more expensive, political consultant and pollster, this time hiring Roger Ailes, a famous figure even then for his role in Richard Nixon’s 1968 campaign, and Lance Tarrance, a prominent Republican pollster from Texas.

Advertisement

As was the case in the Jefferson County election that began his career, McConnell did not formulate his own message to try to win over the voters—again, he left that to his consultants. The message they created was ingenious, entertaining, and factually misleading, and had nothing to do with public policy or political philosophy. Roger Ailes has continued to boast about this “message” for decades after he concocted it.

At least a McConnell campaign aide had a part in it. By studying Senate records, the aide had discovered that Huddleston had missed several floor votes because he was on the road making speeches for “honoraria”—cash he could, under the Senate rules at the time, put into his bank account. McConnell recounts how Ailes explained his plan to exploit this discovery:

“We’re gonna get bloodhounds, because they’re big in Kentucky. And I’ve called Snarfy…. He’s this guy I know. An actor. He looks like he could be from Kentucky. He snarfs…. It’s something he does before he starts a scene. Clears his throat…. So we call him Snarfy…. He’s going to be led by this pack of dogs, hunting for Huddleston, who has clearly been busy giving paid speeches instead of voting. I love it. What do you think?”

I had no idea what to think [McConnell writes]. It was insane. “I think it’s probably better than anything else we got [sic]. What do I have to do?”

“Absolutely nothing. I’ve written the script already. I’ll do it and see what happens. If it fails, you can blame me.”

“Okay,” I said. “That’s a good plan.”

The thirty-second ad ran on Kentucky television stations repeatedly. Everyone saw it. Snarfy and a pack of large, energetic hounds start off on the grounds of the Capitol, then move around the country looking for Huddleston. A narrator claims Huddleston is missing votes on big issues so he can give speeches for money. The kicker is a photo of McConnell with his slogan, “Switch to Mitch.”

“I immediately saw the effect,” McConnell writes. “On the [campaign] trail, people began to approach me, to shake my hand and comment on how funny they’d found the ad. The momentum was just what I needed.” It really was a funny spot.*

Funny, but also misleading. As Newsweek established at the time, Huddleston was present for 94 percent of Senate roll-call votes, a good attendance record. No matter. This one commercial, with some huge help from Ronald Reagan’s electoral juggernaut, carried McConnell to a close victory in November. At forty-two, he had fulfilled his dream; he was a United States senator.

McConnell brags that he was the only Republican to oust an incumbent Democrat that year. “Despite Reagan’s landslide victory” against Walter F. Mondale, he notes that he won by a tiny margin—just 5,100 votes, or about one vote per precinct in the state. But he fails to acknowledge that Reagan’s overwhelming success in Kentucky surely carried him across the finish line. MacGillis reports that Reagan won the state by 283,000 votes, so 278,000 Kentuckians who voted for Reagan also voted for Huddleston, against McConnell. He owed his victory to Reagan and Ailes, two names he failed to mention in his victory speech on election night.

“A win is a win,” McConnell writes, and he knew what to do with his. Just as soon as it was clear that he had won, he began raising money for his reelection campaign six years hence. He quickly built a substantial bank account, and never stopped looking for more. His eager approach to fund-raising impressed his new colleagues in the Senate. Raising money is “a joy to him,” former senator Alan Simpson of Wyoming told MacGillis. “He gets a twinkle in his eye and his step quickens. I mean, he loves it.”

Once in Washington, McConnell appeared to understand that he could not pursue his own ambition as a moderate Republican. “The ultimate goal of many of my colleagues,” he wrote, “was to one day sit at the desk in the Oval Office,” but he “knew deep down” that he wanted to be the Senate majority leader. The increasingly conservative Republican caucus in the Senate was not going to embrace a disciple of John Sherman Cooper, famous in his day for his liberal independence.

So McConnell joined the disciples of Ronald Reagan, who had begun his presidency with the famous declaration that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” McConnell slipped easily into the warrior’s pose, joining the growing band of conservative Republican senators whose primary interest was politics, not policy, and who loved to wage a permanent campaign for partisan advantage. Making his way into the Republican leadership required perseverance. In 1997 he signed on for the job of chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, in effect chief fund-raiser for his colleagues, a thankless task that he apparently loved, and did for two election cycles, twice the average tenure.

McConnell’s reward was to be elected majority whip, the second-ranking position in the Republican leadership, in 2002. Four years later, by the unanimous vote of his colleagues, he ascended to the post of Republican leader—just after the job had to be renamed “minority leader” because Democrats won control of the Senate in 2006. “I felt nothing less than an enormous sense of gratification and an utter thrill that it had, finally, happened”—his long-harbored ambition achieved.

4.

When he writes about his pursuit of personal ambitions, McConnell’s book can be engaging. When he turns his attention to substantive matters, it is more likely to be exasperating. McConnell the partisan warrior never takes a step back to reflect on the events swirling around him, but instead relies on what are known today on Capitol Hill as “messaging talking points”—party propaganda. Facts don’t interest him much.

McConnell on George W. Bush and the war in Iraq falls into this category. Historians may be debating whether Bush was the worst American president, or only one of the worst, but for McConnell, “Bush was an outstanding wartime president.” Bush’s decision to topple Saddam Hussein by force, strongly supported by McConnell at the time, was the proper response to “the rare situation where a regime change clearly needed to occur before another tragic attack was perpetrated on innocent lives.” McConnell, like Dick Cheney, still wants us to believe there was a connection between Saddam and the September 11 attacks. “Al-Qaeda terrorists continued to leave footprints on Iraqi soil,” McConnell writes.

According to McConnell, “there was international agreement that [Saddam] was amassing weapons of mass destruction,” which of course there was not. We now know that if the chief UN inspector Hans Blix had been given a few more weeks to complete inspections in Iraq, the world would have known that Saddam had no secret cache of those weapons.

Toward the end of this brief section of his book, McConnell acknowledges that “of course, this war would become a matter of great controversy…and there are a lot of questions surrounding the wisdom of the decision to invade Iraq.” But he neither asks nor answers any of them, because his objective here is propagandistic, not historical.

The same is true when the subject is Barack Obama, who is assigned the role of the ominous heavy in McConnell’s story. “I had been working for the last twenty-four years to protect the nation from exactly the type of changes I knew he’d be eager to enact,” we learn when McConnell first mentions Obama in an account of his own reelection campaign in 2008. McConnell was convinced long before Obama became president that he had to fight him implacably, as of course he did.

By 2009, this self-described disciple of John Sherman Cooper had become a right-wing political warrior who embraced the tactics and the philosophy of Newt Gingrich, the former Speaker, who first poisoned the politics of Capitol Hill. The end—Republican political triumphs—justified the means, which in this instance were unbridled legislative obstructionism.

McConnell became notorious, especially among Democrats, for the following confession to a reporter for the National Journal in October 2010: “The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president.” Democrats pounced on this as proof of McConnell’s determination to frustrate Obama in every possible way. In his book McConnell writes that his words had never been “taken out of context…more relentlessly.”

People falsely claimed I’d made the statement immediately after Obama was first elected—framing my statement as proof that before anything else, I was out to obstruct the president and cause him to fail—when the truth was that I made it after he had jammed through the health-care bill and the stimulus [both passed in 2009].

McConnell is right about the timing of this remark, but the line he is peddling—that he turned against Obama only after Obama pushed “radical” proposals through a Democratic Congress—is exposed by MacGillis as baloney. The late Bob Bennett, a gentlemanly, old-school Republican from Utah who was defeated by a Tea Party insurgent in 2010, gave MacGillis a detailed account of what McConnell told his Republican colleagues at a retreat shortly after Obama’s inauguration:

Mitch said, “We have a new president with an approval rating in the seventy percent area [Obama’s actual popularity at the beginning of his first term]. We do not take him on frontally. We find issues where we can win, and we begin to take him down, one issue at a time. We create an inventory of losses, so it’s Obama lost on this, Obama lost on that. And we wait for the time where the image has been damaged to the point where we can take him on.”

This was just what happened. Combined with the successful Republican effort to demonize Obamacare (“the worst bill…in the nearly three decades I’d served in the Senate,” McConnell writes, quite preposterously), the idea that Obama was a failure who could do nothing about the gridlock in Washington caught on—even among Democrats.

Since 2011, McConnell and his counterparts in the House of Representatives have been able to frustrate practically every legislative initiative the president offered. The Senate blocked dozens of appointments to federal agencies and courts. At McConnell’s personal insistence, the Senate refused even to hold a hearing on Obama’s nominee to replace the late Antonin Scalia on the Supreme Court.

On just one issue since Republicans retook control of the Senate in 2014 has a bipartisan majority emerged to support meaningful reform legislation, a bill to improve the federal criminal justice system. The Senate Judiciary Committee approved a bill last October to loosen mandatory sentences for drug-related offenses. But when some of his most conservative senators began to complain about this bill in 2016, McConnell abandoned it. The majority leader never brought the bill to the floor for a vote.

McConnell expressed great satisfaction when Republicans regained control of the House in 2010, and of the Senate in 2014. He promised at first that the new Republican Senate would show the country that it could “govern.” Instead it has failed to perform some of its most basic functions.

So nothing worked out for McConnell quite as he hoped. Obama survived, even thrived. In the last year the president’s approval ratings rose; they are now above 50 percent as his presidency draws to an end.

But if McConnell and his colleagues failed to undo Obama, they did sabotage their own conservative cause. Sixteen of the seventeen Republicans who ran for president this year assumed they had to win over “the conservative base,” the true-believing Tea Party supporters and other right-wingers, who, according to the conventional wisdom, would select the party’s nominee. A seventeenth candidate saw another path—to run ferociously against the “stupidity” and gridlock in Washington, to flout conservative orthodoxy on many issues, and to promote his own brew of nativism, authoritarianism, and racism.

So McConnell not only failed to destroy Obama, he helped create Donald Trump. Trump’s success was surely a consequence, in part, of the stalemate in Washington to which McConnell contributed so much.

McConnell dutifully “endorsed” the man Republican voters had chosen as their nominee, but he did so with obvious distaste. Trump’s self-inflicted political wounds, inflicted one after another from July through October, gave McConnell the most discomfiting election season of his long career. By October he was telling reporters who asked him about Trump’s latest misstep, “I won’t talk about that.” His worst moment came with the release of the tape that showed Trump boasting in the crudest language of his conquests of women, a thunderbolt that shattered the unity of McConnell’s caucus and sank Trump’s chances. McConnell criticized Trump for this but did not withdraw his “endorsement.” As this essay was prepared for publication, the Republican majority in the Senate was in grave jeopardy.

This Issue

November 10, 2016

Inside the Sacrifice Zone

Why Be a Parent?

Kierkegaard’s Rebellion

-

*

It can be found at www.youtube.com/watch?v=bcpuhiIDx3Q. ↩