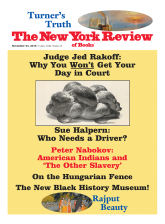

Srjdan, our Serbian innkeeper, is a perfect host. Knowing that we are bound to lose ourselves in the streets of Sombor, a Serbian town near the Hungarian border where the night before we had checked into his bed and breakfast with its opulent furnishings and paintings of lush Italianate beauties, he leads us to a dusty crossroads and points in the direction of Rastina, a tiny village where the road peters into a dusty track by a rickety watchtower. From here we can see the sparkling fence built by Hungary as it marches across vast acres of newly harvested fields of corn. We make our way toward the fence—a formidable ten-foot-high structure with double coils of razor wire affixed to metal posts sunk deep in the ground—and follow it for half a mile or more in the direction of a ruined farmhouse surrounded by bushes.

There are signs of activity on the Hungarian side—diggers and tractors creating clouds of dust as a second layer of fence is prepared. A police car draws up on the other side, and seeing our camera and tripod, an officer asks—in English, the lingua franca—what we are doing. “We are taking pictures for an exhibition,” we tell him. “We have permission from the Serbian police.” “You do not have permission,” he says, “because you are standing on Hungarian soil.” He points through the wire to a small white post that marks the official border, five feet on our side of the fence. International law requires that both countries must agree to the construction of border barriers. The Hungarians did not ask the Serbians for permission to build their fence. Instead they erected it more than three feet inside Hungary, ceding a de facto ribbon of territory to their Balkan neighbor.

We retreat a couple of paces and head for the abandoned farmhouse where we won’t be seen from a Hungarian watchtower; the bushes and outbuildings provide cover for the special shot we are seeking: a wayside crucifix viewed through a diadem of metal thorns. A male guard in the watchtower sees us, picks up his weapon, and slings it over his shoulder with ostentatious deliberation. Now that we are inside Serbia, we ignore him: we doubt if, for all Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s bluster, he would welcome an international crisis resulting from the shooting of European citizens on Serbian territory. Someone in the watchtower switches on music and the tension subsides: another guard—this time a woman—leans from the tower and waves us a cheery goodbye. There were no refugees by the farm buildings, but we see signs they had been there that night and moved on: fresh bits of bun, orange peel, discarded biscuit wrappers, a cigarette packet or two.

We visit the refugee camp set up on the Serbian side near the crossing point at the Serbian town of Horgos. Momcilo Djurdjevic, a doctor from Médecins Sans Frontières, tells us that this part of the border region has become more perilous for refugees, with an increase in “dog bites and other wounds inflicted by unnecessary use of force” since mid-August, during the period in the lead-up to the Hungarian national referendum called by the government to vote against migrant quotas proposed by the European Commission. Before mid-August, incidents of police violence were rare. Now refugees are regularly bitten by dogs, “especially where the physical barriers are less formidable.”

Observing the fence nearby we saw no dogs on the Hungarian side, but despite the coils of razor wire, we could tell how easily it could be penetrated if the guards were not watching. In Serbian hardware stores near the border, sales of wirecutters increased soon after Hungary began building the fence, in July of last year. As one former soldier, now working as a cameraman, put it when filming the construction of the fence: “In the British army they taught us to cross these things in about three seconds.” The doctor explains:

If one group finds an easy place to cross, they’ll tell others who try to attempt the crossing themselves. So if you have a couple of groups that receive the same measure of deterrence by the police or whoever, then that story is shared, and others are deterred from using that crossing point.

Stories do not necessarily deter. “Back in Belgrade,” says the doctor, “I treated several people with dog bites. The patients rested for a couple of days, then made another attempt at crossing. Those who are determined enough are going to go on trying. The number of people who get through to the European Union is related to their resourcefulness, their bravery, and their luck.”

Advertisement

His words are confirmed by Afghan refugees living temporarily in the Zeytinburnu district of Istanbul. When asked what they are waiting for, they say for Europe to open its doors again. A young man told us he is twenty, from Kabul, and has been in Istanbul since the possibility of crossing the Aegean to the Greek islands was closed under the agreement between Turkey and the EU in March. Why doesn’t he try traveling by land, through Bulgaria, Serbia, and Hungary, as fifty to two hundred migrants have each day this year? “We know we will be beaten many times, by the Bulgarian police and the Hungarian police, and that we will be thrown back many times across the borders before we succeed,” he says.

The major effect of measures such as building fences and patrolling with dogs is to decrease the number of people entering the EU. But as one official from Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, put it, “Migration is like a balloon. You squeeze it in one place, it gets bigger somewhere else.” This is the argument that the fence-builders in Hungary, Bulgaria, or elsewhere refuse to listen to. Since the “closure” of the western Balkan route, only one hundred to two hundred a day have managed to find a way from Turkey through Bulgaria or Greece into Serbia. Contrast that with the 21,294 who reached Italy from North Africa in August, an average of 687 a day. To completely stop migration is virtually impossible: people will always find a way because the fences aren’t completely effective—they are material obstacles, while it is people who guard them. “There are different kinds of people,” Momcilo Djurdjevic says cautiously.

Some [officials] will come to an agreement by accepting money. So the flow is virtually unstoppable. Those who are deterred are likely to be the most vulnerable, those with families and kids. It’s only the fittest who make it and the most vulnerable are left behind.

Despite the dangers, some unaccompanied women still attempt the journey. Dalal Hasan, in the Subotica refugee camp, is fifty-eight, from Aleppo in Syria. Her husband, a taxi driver, was killed by an air strike in 2014. She left the city in February of this year when life became impossible, she said. She was traveling initially with her son, his wife, aged thirty, and their two children, aged seven and four. After they reached Greece the western Balkan route was officially closed. Her son went ahead and finally reached Germany. Defying the norm, they have traveled without money during the entire journey, Hasan says. Their fellow refugees helped by paying smugglers when necessary. The smugglers in Macedonia were the worst—all fellow Syrians and Afghans. They beat them when they would not walk fast enough through the forest. They locked them in rooms, smashed the windows, and terrorized them. She weeps often as she tells her story. At one point, the smugglers told her relatives in Germany, on the phone, that they would kill them one by one unless more money was paid.

The camp on the Serbian side near Horgos is quiet under a sun that still scorches in mid-September. Most of the people seek the shade of the makeshift tents of sheets and tarpaulins that have been erected haphazardly next to the wall of blue steel containers that form the official transit buildings on the Hungarian side of the fence. Admission to the transit area is limited to fifteen people a day at Horgos, fifteen more just up the fence at the Hungarian village of Kelebia. The Hungarian measures have created a bottleneck on what is left of the western Balkan route. There are now more than six thousand refugees in Serbia, in twelve camps. While some still try to reach the West illegally, with the help of smugglers through Montenegro, Bosnia, and Croatia, most of the people here appear resigned to waiting patiently for the chance to cross legally, through Hungary. They will have a long wait. A single man may have to spend up to thirty days in the blistering heat of these containers, but families with children usually pass through much more quickly.

Once they have made their claim for asylum, the refugees are supposed to take temporary IDs they are issued to a holding camp in Hungary. But very few decide to remain in Hungary. By September 25, according to the Hungarian Office of Immigration and Nationality, 7,732 had entered Hungary through the two transit zones. Only 372 had been granted protection. The others, plus the 20,000 who entered Hungary before the border regime got tougher on July 4, have all moved on to Austria or Germany. Some reached the notorious “Jungle” near the French port of Calais, now being cleared by the French authorities, from which they sought a passage to Britain by walking through the Channel Tunnel or hiding beneath the canopies of tractor-trailer trucks.

Advertisement

No journalist has been admitted into the Hungarian transit area, which has basic plumbing and electricity, although the offices have air-conditioning, judging from the vents exhaling into Serbia. By the time we arrive at the camp on the Serbian border, today’s batch has already passed through. A water trough where people wash their utensils and children douse themselves is fed by a pipe from Hungary.

We pass a makeshift mosque, now empty, since it is not yet time for the midday prayer. An Iranian translator who has lived in Serbia for two decades suggests that the Iranians are the least religious Muslims in the camp. Most have left the country for political reasons. Their women never wear the chador as required by law in Iran. Like others they want to go to Europe because they want to improve their lives. But they cannot say that to the authorities, since only persecution will count as the basis for a claim to asylum. Iran may be unpleasant for some, but it is not considered dangerous, like Afghanistan or Eritrea. Those who want to go to Europe to create a better life for their children must lie—or at least tweak the facts—to make the case that they face dangers at home.

Mohammed is a highly qualified Moroccan water engineer who admits to being an economic migrant. We met him first in Athens in December 2015. He reached Austria in May, and has now reached Cologne. He has a high-tech skill for which there is much demand in Europe—but if he had applied for admission to a European country in Morocco he would have stood no chance at all. He says he’s forced into illegality by the system. There’s no legal way for him to do a job that he’s good at in a country that needs his skill. All he wants to do is work for ten years in Germany before returning to Morocco.

Mustafa, a fine-looking young man in a flimsy T-shirt, is playing Eastern music on his boom box in the Serbian camp at the Horgos crossing. His story and that of his family reveal the complexity of the migrant’s predicament. There is no clear distinction between the “push” factor of political persecution and the “pull factor” of economic opportunity. The family, from Bagram in Afghanistan, left at the beginning of this year when a local commander working with the government wanted their land. Mustafa and his brother decided to leave. They still do not know what became of their father. Mustafa’s elder brother had enough money to get them as far as Greece. He is reticent about his method of transport—concerned perhaps that we might expose the smugglers. He expects, however, to be crossing tomorrow to Hungary, and takes us to the acting “camp commander” who has the list.

The commander, an impressive-looking man of about fifty who speaks good English, was, he tells us, a weapons trainer in the Afghan army and held the rank of colonel, a status that clearly put him at risk in his home district of Logar, southeast of Kabul, where Taliban attacks are frequent. He worked with Americans, Australians, and even some Hungarians who formed part of the NATO contingent. “The Taliban came to my father,” he said, with a gesture implying their threats. The colonel introduced us to a considerable number of family members—ten of them including himself, his children, mother, and sisters—and nodded assent when we asked if he had employed agents or “people smugglers” to get them as far as Serbia. The cost—around $100,000—is consistent with the going rate of around $10,000 per person that the smugglers are presumed to charge to bring people from Afghanistan to Europe.

To fund this journey the colonel sold his house, his land, and his cars, leaving him more or less destitute. They took the usual route through Iran and on to Turkey. From Izmir they made the perilous journey to Chios in Greece, crossing the dangerous waters in small boats, one of which capsized, resulting in the deaths of seventeen people. Realizing that there was no work to be found in Greece, they walked for ten days to Serbia.

He would like to work in Austria, or perhaps even Hungary. He has a disc containing pictures of the Hungarians he knew in Afghanistan. We suggest that he tell the immigration people about them, and that he put them on his Facebook page when he crosses the border tomorrow.

Will the colonel and his family be safe? If their asylum claims are rejected, there is a distinct possibility that after spending all their wealth and the months of exhausting travel they could find themselves returned to Afghanistan under an agreement reached in Brussels on October 5 between the European Union and the Afghan government. Despite official denials of any “linkage,” the repatriation plan that promises a “dignified, safe and orderly return of Afghan nationals to Afghanistan who do not fulfill the conditions to stay in the EU” is clearly a quid pro quo for an agreement on a $3.75 billion package of development aid reached between the Afghan government and European Union the previous Sunday.

In view of the Taliban’s recent resurgence in Afghanistan, with the group now controlling more territory and population than at any time since the US invasion of 2001–2002, with two provincial capitals under siege in the south and the northern city of Kunduz—far from the Taliban heartland—under recent attack, the deal means that thousands of Afghans whose asylum claims are rejected will be returned to an increasingly dangerous war zone.

As The New York Times pointed out on October 5, during 2015, more than 50 percent of Afghan requests for asylum were rejected out of some 177,000 claims. This means that tens of thousands of people may now be sent home. As the Times explains,

In addition to the fact that even Afghan districts and major highways once declared safe are now threatened or overrun by the Taliban, the returnees from Europe will go back to a dire economic crisis, with an unemployment rate of about 35 percent and about 400,000 young people entering the job market every year.

The response of the Hungarian government has grown consistently tougher with each month that has passed. On October 2, the government held the new referendum on the migrant quotas proposed by the European Union. The result was a bitter disappointment for Prime Minister Orbán—although he tried to spin it as a victory. Despite an extensive publicity campaign costing $40 million (more than the combined Leave and Remain campaigns in the UK’s Brexit referendum in June), only 41 percent of the Hungarian electorate cast a valid vote, while 53 percent stayed away and 6 percent spoiled their ballots.

Under Hungarian law, over 50 percent of the electorate must cast a valid vote for the referendum to be valid. Many of those who voted “no” to migrant quotas did so, as they saw it, in defense of Hungarian sovereignty rather than against genuine refugees, not least because the way the question was framed made it almost impossible to vote “yes.” With the opposition urging a boycott or invalid vote, the result shows a dogged refusal by the majority of the Hungarian electorate to be swayed by months of wall-to-wall, often xenophobic, government propaganda.

Despite this setback, the government has proposed amendments to the Hungarian constitution that would prevent accepting groups of migrants in the future—effectively building the referendum question into law. Orbán’s fence-building and anti-immigrant rhetoric, says Gerald Knaus of the European Stability Initiative, have injected “a far-right virus into the bloodstream of Europe’s political center.” As Timor Sharan of the International Crisis Group told the Times, European governments are sending back a large number of Afghan asylum seekers not because of the realities in Afghanistan, but because of anti-immigration sentiment.

How different the European approach seems from the reception Hungarian refugees received in Western Europe after the 1956 Hungarian revolution. The strains on Austria, which had only achieved internationally recognized sovereignty in May 1955 after a decade of occupation by Soviet and Allied forces, were enormous. The country, which had suffered military defeat after uniting with Germany under the 1938 Anschluss, or union, was already sheltering some 120,000 people displaced during World War II. Yet despite the pressures this new influx placed on the country’s services, the Hungarians in 1956 were received with extraordinary warmth. Farmers provided straw for them to sleep on in empty barns or war-damaged houses. Within a short time the refugees were being transferred to organized camps, with each person provided with a daily nutrition allowance of 2,400 calories, clean, warm clothes, along with pocket money, toiletries, and cigarettes. By 1959 many had been resettled abroad, with more than 38,000 in the United States, 25,000 in Canada, and 20,000 in Britain.

On leaving Serbia, we drove home through Hungary and Austria, pausing to visit the famous bridge at Andau, where refugees crossed the Einser Canal after Russian tanks moved into Budapest to suppress the Hungarian revolt. As a student volunteer, one of us had been on the canal in December 1956 at the height of the refugee crisis, when the Soviet crackdown had caused an exodus of more than 300,000 people, or up to 4 percent of Hungary’s population. The refugees arrived in small parties, slushing through the swampy marshland bordering the frozen canal, its ice too fragile to support the weight of a human. After the Russians blew up the bridge, the volunteers—from a motley group of organizations including the Knights of Malta, Save the Children, and the International Rescue Committee—devised a relay of inflatable dinghies on ropes to ferry people across the canal.

On the Hungarian side we risked being captured or shot, as happened to two of our party—a Norwegian and an American who spent several weeks in a Budapest jail before being released in an exchange with the US. It was bitterly cold, with an icy Siberian wind that cut through one’s clothes. Many of the refugees were dangerously underclad, without adequate coats or boots. After the Soviets had closed the frontier and a woman had been shot, the refugees hid in the reeds and woods during the day to emerge after sundown like hunted animals. They had to use what cover they could to dodge the searchlights and flare guns the border guards fired to expose them.

Once reassured that they were safely in Austria, the refugees were bundled into an assortment of vehicles—mostly jeeps and Volkswagen minibuses—and taken to a holding center in the village of Andau, some seven miles along a muddy track, half-frozen and sludgy, where the VWs often got stuck. The holding center—in a village school—had a pungent odor of cocoa, drying woollens, and diapers. After toddlers and babies had been injected with an antidote to counter the dangerous effects of sleeping tablets they had been given to keep them from alerting the border guards, the volunteers had to keep them awake for several hours to prevent them from getting pneumonia. One method was to place them on chamber pots and to shuffle them like curling stones between volunteers while seeing that their eyes remained open.

Sixty years later, the reconstructed bridge at Andau is now a heritage site. There are old pictures of silhouetted figures struggling across the remains of the bridge before it collapsed in the canal, memorials with the names of the fallen, old warnings not to cross the border in German, English, and French. These compete for attention with posters celebrating the canal’s rich bird life. The bridge, as one star-fronded notice informs us, is Number 13 on the Iron Curtain Cycling Trail, an initiative of the European Union. When we talk with a group of Austrian tourists, the irony of a new metal curtain escapes them. Today’s refugees, says one, are not like the Hungarians: they do not belong to our culture.

The same ambivalence is reflected in a telegram from 1956 now in the archives of the Austrian foreign ministry, sent by Hungarian refugees who were making a new life in Australia: “We the Hungarian Community in Brisbane, wish to express our most sincere gratitude for the help your government extended to our brave compatriots wounded in their desperate struggle for freedom.” The telegram’s next sentence reads: “During the centuries your country has often helped us in our historical role of being Europe’s bulwark against the hordes of the East, but help has never been more appreciated than in this critical hour.”

In 2015, at the height of the crisis, hordes of volunteers came forward to help the refugees, numbered in the hundreds of thousands, who crossed into Hungary. In the crowded underpasses of the Keleti railway station in Budapest, along the freeway to Vienna when refugees set out to walk, and at countless places along the unfenced southern border, a common sense of humanity overcame fear and distrust. The same feeling of concern was shared by many police officers, who were placed in an impossible position by a lack of basic resources such as interpreters, transport, and mobile toilets.

The denial of those resources was clearly political: in defending “Christian Europe” the country must not appear to be too welcoming. The irony was recently underlined in a speech on October 18 by Zoltán Balog, minister of human resources, at a commemorative event in Berlin marking the sixtieth anniversary of the Hungarian uprising.

While acknowledging that “human suffering” was common to the refugees of 1956 and the mass movement of millions today, he claimed that there was also an important difference. The 1956 refugees were “people of a similar cultural background” and (in contrast to the present) it was a “one-off emigration event.” Today’s migration would continue “until these people have a chance of making a living in their own homelands, within a fairer world order.” Common humanity, it seems, is less than universal.