In the fall of 1940, when Luftwaffe planes were dropping tens of thousands of bombs over British cities and ports every night, and when American intervention in the war seemed more and more necessary, Eleanor Roosevelt published a short book entitled The Moral Basis of Democracy. Framed around Christ’s message of treating others with kindness, the golden rule she believed was essential to the flourishing of a healthy democracy, she asked all Americans to rise to their better selves and “practice a Christ-like way of living.”

This was not a question of belief in his divinity, she wrote. It was rather his example of a life of gentleness, mercy, and love that would bring “the spirit of social cooperation…more closely to the hearts and to the daily lives of everyone…[and] change our whole attitude toward life and civilization.” Democracy, above all other forms of government, “should make us conscious of the need we all have for this spiritual, moral awakening.”

A social reformer and a crusader for human rights, she saw poverty, inequality, and racial discrimination rampant in the United States, all deepened by the Great Depression despite Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Democracy’s true essence, she argued, is fraternity, sharing, sacrifice, and an ethic of responsibility for the neighbors we know as well as for the people we don’t know. “That means an obligation to the coal miners and sharecroppers, the migratory workers, to the tenement-house dwellers and the farmers who cannot make a living.” Americans had a strong work ethic, she noted, but it was not enough to work for themselves—rather they must “serve the purposes of the greatest number of people.”

Like Eleanor, Franklin Roosevelt deeply believed that the core purpose of true democratic government was to better the lives of its citizens, especially the weakest among them. And like Eleanor, Franklin was an idealist, but he was also a master politician, an idealist without illusions, who possessed a tough-minded understanding of how the world—and Congress—worked and was willing to dirty his hands and do everything necessary to accomplish what he believed were good ends.

Eleanor Roosevelt lived in that jostling, fighting world but was not wholly of it. She campaigned for her husband’s elections and fought to build support for controversial policies. She knew firsthand that everything in Washington was a fight, a clash of interests, whether to advance the good or beat back the bad. But while for FDR there was no transcending the morass of politics, she sought a different way. Max Weber had written in 1919, “He who seeks the salvation of the soul, of his own and of others, should not seek it along the avenue of politics.” To Eleanor, spiritual salvation and social justice were closely linked, and that drove her to seek change by reaching people’s souls. She became one of the rare moral leaders of her time—Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and Nelson Mandela were among the others—who heeded a principled moral code and sought to raise the aspirations and efficacy of an expanding cadre of followers. These leaders worked to create something new, a radical change in the world.

In Eleanor Roosevelt: The War Years and After, the third and concluding installment of her groundbreaking and authoritative study of the most admired and respected American First Lady, Blanche Wiesen Cook focuses on the complex and controversial period from 1939 to 1945. The war years especially illuminate Eleanor’s unflagging and optimistic activism—her positive influence on public opinion and sometimes on her husband, her determination to keep equal rights, union rights, human rights, education, and economic security on the agenda.

Amid the most brutal war in history, when faith in humanity sagged to a low ebb, Eleanor offered hope. “Her interest and concern empowered impoverished communities and healed the wounded,” Cook writes. Her ceaseless wartime travels spread her vision of a better future around the country and around the world, from migrant worker camps in California—“You must read Grapes of Wrath,” her friend Lorena Hickok urged—to army bases in the Panama Canal Zone, from the Gila River Japanese-American internment camp in Arizona to Civilian Conservation Corps camps in Maine, Texas, and Illinois, from New Zealand to war-ravaged England. Her appearances in the least likely places recalled a celebrated New Yorker cartoon from 1933 that showed two coal miners in a dark tunnel, both wearing head lamps; one looks up from his work and exclaims, “For gosh sakes, here comes Mrs. Roosevelt!”

Though she was the face of American idealism for a vast number of people, Eleanor was always convinced that she was not doing enough—as though she might rectify the tortured world single-handedly and person by person. “She has wanted desperately to be given something really concrete and worthwhile to do in the emergency and no one has found anything for her,” her assistant Tommy Thompson told Eleanor’s daughter, Anna, in 1940. “She works like Hell all the time.” In the summer of 1943, wearing a Red Cross uniform, she visited army hospitals in the Pacific—in New Zealand, Australia, Samoa, Guadalcanal. Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, her escort, was deeply moved by her visit. She didn’t merely shake hands with the chief medical officer and depart, like the usual VIP. “She went into every ward,” Halsey wrote,

Advertisement

stopped at every bed, and spoke to every patient: What was his name? How did he feel? Was there anything he needed? Could she take a message home for him? I marveled at her hardihood, both physical and mental; she walked for miles, and she saw patients who were grievously and gruesomely wounded. But I marveled most at their expressions as she leaned over them. It was a sight I will never forget.

Two vital issues dominate Cook’s new volume: race and rescue. Both put Eleanor Roosevelt at odds with the Roosevelt administration. She had a holistic, indivisible idea of justice—she identified the sufferings of African-Americans reenslaved under Jim Crow with the plight of Jews desperate to escape from the horrors of Nazified Europe.

In the struggle for civil rights she used her standing as First Lady to create symbolic victories. In 1939, when the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to let the black singer Marian Anderson perform in their Washington concert hall, she publicly resigned from that elitist organization and arranged for the concert to be held on the Great Mall at the base of the Lincoln Memorial. “It seems incredible when we are protesting the happenings in Germany,” she wrote to her sister-in-law, “to permit intolerance such as this in our own country.”

That concert, attended by 75,000 people, was a triumph that exposed the absurdities and cruelty of racism in America. But Eleanor was frustrated in her attempts to go further. In the summer of 1940, as the nation began to mobilize its resources for possible war, she urged FDR, Navy Secretary Frank Knox, and Assistant Secretary of War Robert Patterson to meet with NAACP officials to discuss desegregation in the military. Their meeting took place in late September, but ten days later the White House issued a press release reaffirming the War Department’s policy

not to intermingle colored and white enlisted personnel in the same regimental organizations. This policy has been proven satisfactory over a long period of years and to make changes would produce situations destructive to morale and detrimental to the preparations for national defense.

Eleanor kept pushing, and in 1943 she helped African-American pilots stationed at the Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama win deployment on combat missions. It seemed a minor gain, but it had an enduring national effect, especially after the Tuskegee airmen, derided by white locals as “Eleanor’s niggers,” won praise for heroism in battle. Still, real change would have to wait for Harry Truman’s executive order in July 1948 abolishing segregation in the armed forces.

The First Lady’s activism placed her in a delicate position. She always insisted that she spoke for herself “as an individual” and not for her husband or his administration. But that was not how most people saw it, including disapproving members of the administration. Indeed, at times FDR’s policies and priorities were, as Cook remarks, “at cross-purposes” with his wife’s.

For the president, civil rights were above all a political issue. His New Deal programs did much to help African-Americans during the Depression, and he overturned Woodrow Wilson’s policy of segregation in federal agencies. But Roosevelt always had to worry about keeping the support of the powerful white southern flank of his New Deal coalition, and the war only deepened that dependence, since white southerners in Congress were among the strongest supporters of his interventionist policies. Even so, Eleanor “always believed,” Cook writes, that he and she “shared the same goals for justice and democracy.” As Cook elegantly captures it, “the dreadful circumstances mandated their opposing views as well as their collaboration and cooperation.”

On the fateful question of the rescue of hundreds of thousands of Jews desperate to leave Europe, Eleanor again came into conflict with the administration. She had a few small victories—for example, overriding the State Department and securing permission for eighty-odd Jewish passengers, fleeing Europe, to disembark from the SS Quanza in the fall of 1940; and she helped organize Kindertransporten so that vulnerable children, mostly Jewish, could find havens in Britain and North America.

But these were only ripples in a desperate tide. Anti-Semites had important positions in the State Department, and President Roosevelt didn’t object to Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long’s policy of slamming the country’s door shut on Jewish refugees. “We can delay and effectively stop for a temporary period of indefinite length the number of immigrants into the United States,” Long wrote in an intradepartmental memo in June 1940. “Franklin, you know he’s a fascist,” Eleanor said of Long. “I’ve told you, Eleanor, you must not say that,” he replied. Cook comments that “she said it, and he listened, even if he chastised her for it: this pattern was at the core of their relationship.” She was his “conscience,” and he was her “barometer.” But in the matter of rescuing Jews from Hitler’s persecution, this dynamic of theirs proved tragically inadequate.

Advertisement

As a young woman, Eleanor herself had showed signs of anti-Semitism, though it was, in Cook’s words, “impersonal and casual, a frayed raiment of her generation, class, and culture which she wore thoughtlessly.” But even as First Lady she revealed vestiges of that patrician bigotry. In 1939, answering the letter of a former German friend who defended Nazism, she wrote, “I realize quite well that there may be a need for curtailing the ascendency of the Jewish people, but it seems to me it might have been done in a more humane way by a ruler who had intelligence and decency.” Cook offers a measured interpretation of this repellent statement, commenting that, since Eleanor was “ever the peacemaker,” she “juggled” between her own beliefs and those of her anti-Semitic friends. Still, writes Cook, “It is impossible to know whether her contemptuous reference to Jews was intended to offset [her former friend’s] harsh letter, or whether it actually represented a lingering feeling she worked throughout her life to uproot.”

But Eleanor’s efforts on behalf of refugees, her later championing of the new state of Israel, and her work as a founding trustee and visiting lecturer at Brandeis University all corroborate Cook’s judgment that “ER’s personal commitment to her Jewish friends and her commitment to end bigotry evolved slowly but were absolute.” In April 1945, when American troops entered Dachau, Eleanor lamented that America had not stood up “against something we knew was wrong…. We did nothing to prevent it.”

That month, Franklin Roosevelt died. Not long after, a valedictory for “Eleanor Roosevelt First Lady” appeared in the Democratic Digest. It echoed Tom Joad’s great departing words in Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath:

Wherever there are battles to be fought or injustices overcome, wherever there are people—individuals or masses of people—who need a friend, Eleanor Roosevelt will be there somewhere, very likely in the background…doing her job. And so, it’s goodbye to Eleanor Roosevelt, First Lady, but not goodbye to Eleanor Roosevelt.

That prophecy, written by Eleanor’s longtime friend and former Associated Press reporter Lorena Hickok, got it right.

Except that Eleanor Roosevelt did not remain in the background. During the post–White House years, she became a leading figure of American liberalism. In a fast-paced epilogue, Cook sketches out the last seventeen years of Eleanor’s life, during which she added to her husband’s astonishing legacy and created her own.* Her greatest achievement was her skillful leadership of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, an unprecedented global charter whose foundation was FDR’s vision of extending his Four Freedoms—freedoms of speech and religion and freedoms from want and fear—“everywhere in the world.” No one knew better than Eleanor that they needed to be extended at home as well. She passionately supported the rising civil rights movement, and was appointed by President Kennedy as chair of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women in 1961, the federal government’s first acknowledgment of the postwar feminist movement.

In her book Tomorrow Is Now, published in 1963 after she died, Eleanor wrote about the future with the hope and idealism that defined the course of her long, tumultuous life:

With proper education…with a strong sense of responsibility for our own actions, with a clear awareness that our future is linked with the welfare of the world as a whole, we may justly anticipate that the life of the next generation will be richer, more peaceful, more rewarding than any we have ever known.

Reflecting on her work as First Lady in the autobiographical This I Remember, Eleanor wrote, “I think I lived those years very impersonally. It was almost as though I had erected someone outside myself who was the President’s wife.” Had there been space for a separate, private, authentic existence? Franklin and Eleanor had a truly indissoluble bond. It survived the intense pressures of an extraordinary dozen years in the White House and outlasted his affairs and flirtations.

A forlorn, insecure little girl had been told by her unhappy mother, “You have no looks, so see to it that you have manners.” Her adored father was the alcoholic, playboy brother of Theodore Roosevelt. By age nine, Eleanor had lost both her parents, but she kept the family name when she married her distant—and supremely self-confident—cousin Franklin in 1905. They raised five children and lived in Manhattan, Hyde Park, Albany, Washington, and Campobello Island.

It was a seamless, privileged life—until it fell apart. In 1918 Eleanor discovered her husband’s affair with her social secretary, Lucy Mercer. That revelation traumatized her and permanently transformed their marriage, which became more collaborative than intimate. Ultimately it led her toward what she called “the budding of a life of my own,” an independent, self-directed existence, and it freed her to serve others outside the tight Roosevelt nest. It also liberated her to form new friendships—platonic and romantic, conventional and unconventional, with men and women, married and unmarried. However unwilled, the Lucy Mercer affair was the start of a new and richer life for Eleanor.

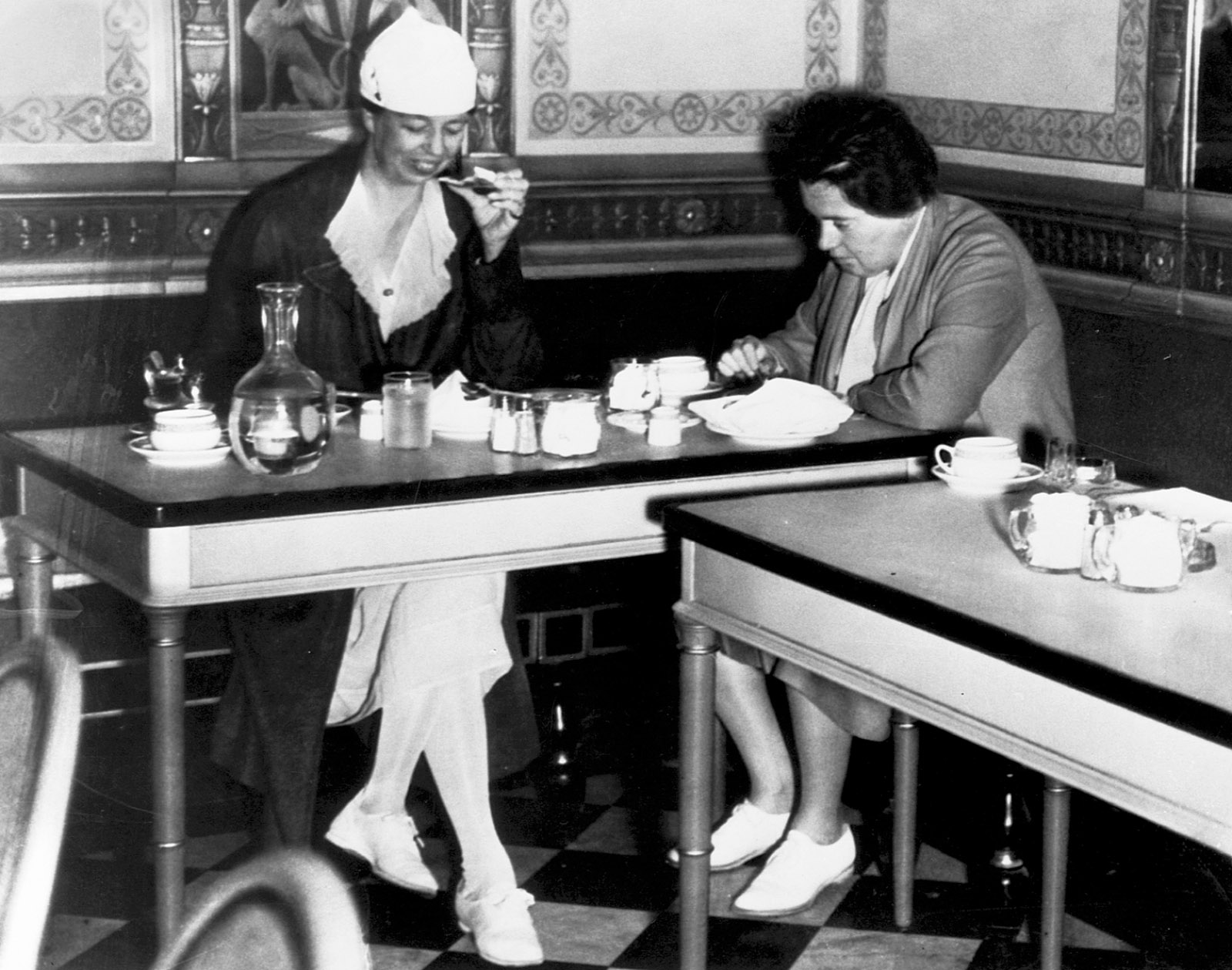

At the center of Susan Quinn’s fascinating and gossipy Eleanor and Hick is Eleanor’s own “love affair,” as Quinn puts it, with the AP reporter Lorena Hickok. In 1932, as Eleanor campaigned around the country for her husband, Hickok asked the AP to assign her to that beat. “She’s all yours now, Hickok,” an AP editor wired. For weeks, Hickok, at age thirty-nine a decade Eleanor’s junior, was her constant companion. As the Roosevelt Special traveled from town to town, they shared a compartment and got to know each other, exchanging stories of difficult childhoods. “May I write some of that?” Hick asked. “If you like,” Eleanor replied. “I trust you.”

On election day in November 1932, Hickok joined the Roosevelts and their inner circle for supper at their home on New York’s East 65th Street. Eleanor greeted her at the door. “When I came in,” Hickok recalled, “she kissed me and said softly, ‘It’s good to have you around tonight, Hick.’” Over the next few months, Quinn writes, “A secret intimacy…developed between them. When they had to part, their final words to each other were ‘je t’aime et je t’adore.’” As for FDR, accustomed by then to Eleanor’s separate life, he accepted his wife’s new friend—so long as it didn’t make the papers.

“Hick, my dearest, I cannot go to bed tonight without a word to you,” Eleanor wrote the day after her husband’s dramatic inauguration in March 1933. “You have grown so much to be a part of my life that it is empty without you even though I’m busy every minute…O! darling, I hope on the whole you will be happier for my friendship…. All my love.”

That letter was the first of several thousand they would exchange, an honest, transparent chronicle of their relationship. “My dear if you meet me, may I forget there are other reporters present or must I behave?” Eleanor asked Hick that spring. “I shall want to hug you to death. I can hardly wait.” Was their relationship a sexual one? Ever since Blanche Wiesen Cook disclosed the intimate nature of their friendship in the first volume of her biography in 1992, a scholarly consensus has emerged to the effect that, yes, Eleanor and Lorena were “romantic.”

Complications came quickly. “I do understand your joy and pride in your job, and I have a deep respect for it,” Eleanor wrote to Hickok in April 1933, but she was sure that Lorena would have “a happier time” with her and without responsibilities for the AP. So Hickok, vulnerable to the quiet force of Eleanor’s will, gave up her job as a reporter, her paycheck, and her professional identity, moved into the White House, and went to work as a field investigator for FDR’s Federal Emergency Relief Administration.

Hickok’s sacrifice marked the peak of their union. For her, there followed professional frustration, financial insecurity, and an unbalanced relationship with the woman who’d rewritten her life. Already in 1935, Quinn remarks, “Hick’s intense craving for intimacy was beginning to feel suffocating to Eleanor.” Eleanor herself admitted to Lorena, “You have a feeling for me which I may not return in kind.” Eleanor kept her friends “forever,” but her circle of affection was not exclusive. “She was always going to be tied not only to a husband,” Quinn writes delicately, “but to bonds of duty and friendship with many others.”

New relationships were formed. For several years in the 1940s, Hick and Judge Marion Harron, Quinn notes, were “a couple,” while Eleanor grew close to the youth leader Joe Lash and later to Dr. David Gurewitsch, her primary physician—“I love you as…I have never loved anyone else,” she wrote to the young Dr. Gurewitsch in 1956. Over the years, Eleanor and Hick drifted further and further apart. Yet a few weeks before Eleanor died, she visited Hick in her small apartment in Hyde Park. “She stayed more than an hour,” Hick wrote, “and we had a long, quiet, relaxed, intimate talk that I shall always treasure.”

-

*

Allida Black’s Casting Her Own Shadow: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Shaping of Postwar Liberalism (Columbia University Press, 1996) examines in depth that most remarkable time of her life. ↩