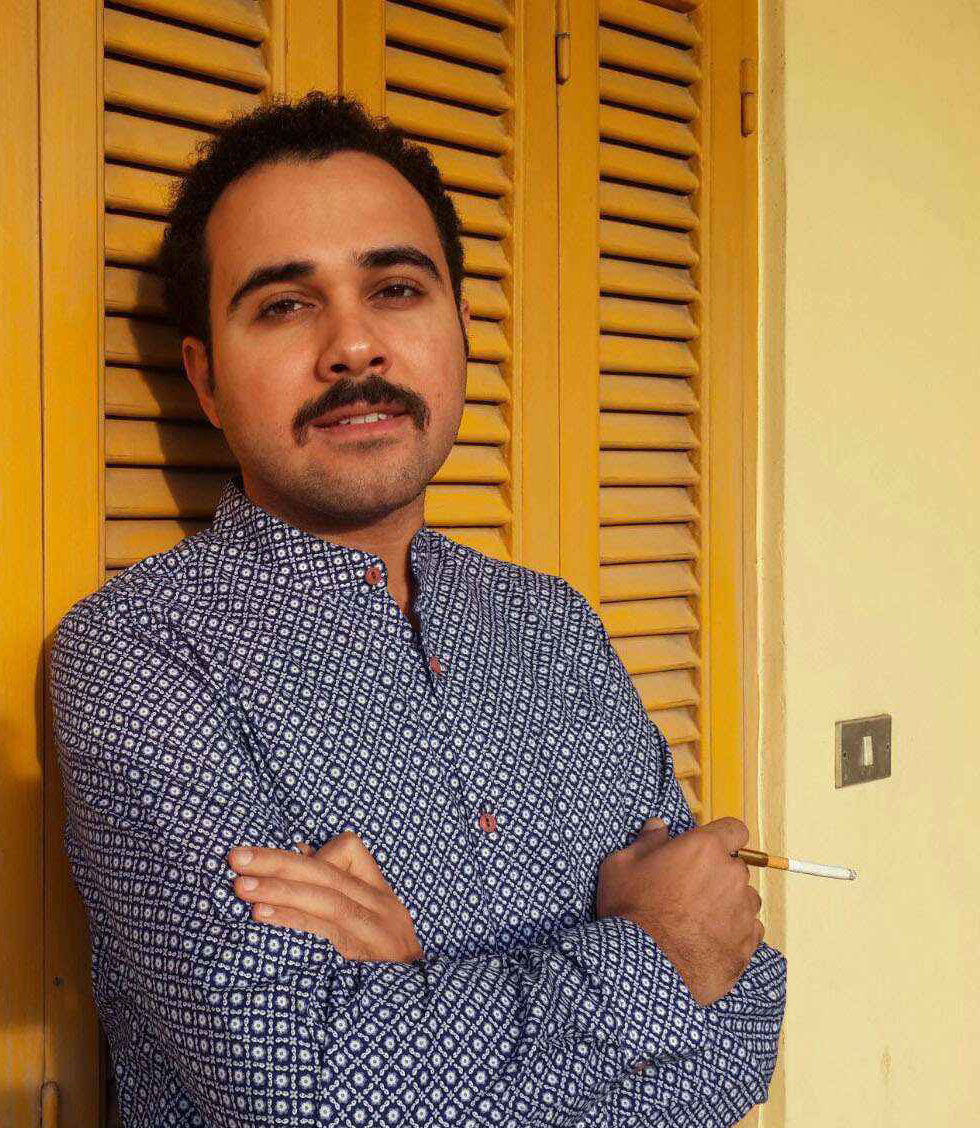

I first heard the name Ahmed Naji at a PEN dinner last spring. I looked up from my dessert to a large projection of a young Egyptian man, rather handsome, slightly louche-looking, with a Burt Reynolds moustache, wearing a Nehru shirt in a dandyish print and the half smile of someone both amusing and easily amused. I learned that he was just thirty and had written a novel called Using Life for which he is currently serving a two-year prison sentence. I thought: good title. A facile thought to have at such a moment but it’s what came to mind. I liked the echo of Georges Perec’s Life: A User’s Manual—the coolness of that—and thought I recognized, in Naji’s author photo, something antic and wild, not unlike what you see when you look at pictures of Perec. You could call it judging a book by its cover: I’d rather think of it as the readerly premonition that this book might please me. If he had written a book called Peacocks in Moonlight and posed for one of these author portraits where the writer’s head is resting on his own closed fist, I would have been equally shocked and saddened to hear he was in prison, but perhaps not as keen to read it.

As I was having these unserious thoughts the contents of the novel were being roughly outlined for us all from the stage. It sounded intriguing: a kind of hybrid, with certain chapters illustrated as in a graphic novel, and with a comic plot concerning a dystopian Cairo, although it was in fact the novel’s sexual content that had landed its author in jail. Though the novel had been approved by the Egyptian censorship board, a sixty-five-year-old “concerned citizen,” upon reading an excerpt in the literary weekly Akhbar al-Adab, had felt so offended by it that he made a complaint to the local judiciary, who then charged Naji and the editor of the weekly with the crime of “infringing public decency.” (The editor is not serving a jail sentence but had to pay a fine.) There was, to me, something monstrous but also darkly comic about this vision of a reader who could not only dislike your prose but imprison you for it, although of course at the dinner the emphasis was necessarily on the monstrous rather then the ludicrous. But when I got home that night I found an online interview with Naji in which the absurdity of his situation was not at all lost on him:

I really enjoyed the dramatic statement of that plaintiff reader. He told the prosecution that he buys the journal regularly for his daughters, but that one time, his wife walked into the room showing him my published chapter and ridiculing him for bringing such writing into their home. He said his “heartbeat fluctuated and blood pressure dropped” while reading the chapter.

Naji seemed bleakly amused, too, by the months of semantic debate that had led to his prosecution, in which the judges sophistically tried to separate fiction from a non-fiction “essay,” determining finally that this extract was in fact the latter, and so subject to prosecution as a kind of personal revelation:

According to their investigations and official documents, my fiction registers as a confession to having had sex with Mrs. Milaqa (one of the characters in my novel), from kissing her knees all the way to taking off the condom. They also object to my use of words such as “pussy, cock, licking, sucking” and the scenes of hashish smoking. Ironically, this chapter speaks of the happy days of Cairo, as opposed to the days of loss and siege dominant in the remaining chapters. This specific chapter is an attempt to describe what a happy day would look like for a young man in Cairo, but perhaps a happy life feels too provoking for the public prosecutor!

Which sounded even more intriguing. A few days later I’d managed to contact Naji’s friend and sometime translator Mona Kareem, who sent me a PDF of Using Life (itself translated by Ben Koerber) to read on my Kindle. It opened with a beautiful line of Lucretius, and I felt immediately justified in my superficial sense of kinship: “Forever is one thing born from another; life is given to none to own, but to all to use.” And as I read on, the novel’s title took on a different resonance again, for here was a writer not content to use only one or two elements of life, no, here was a guy who wanted to use all of it:

In September, as the city’s residents were just beginning to recover from the most traumatic summer of their lives, there came a series of tremors and earthquakes that would be known as “The Great Quake.” It resulted in the destruction of nearly half the city. The there was an eruption of sinkholes that swallowed entire streets, and distorted the flow of the Nile…The sinkholes did not spare even the pyramids, and nothing could be done for the Great Pyramid itself, which was reduced to a simple pile of rubble. All that was left of our great heritage—our civilization, our architecture, our poetry and prose—would soon meet a fate even worse than that of the pyramids. Everything collapsed into the earth or was buried under oceans of sand.

So here was the epic mode—the fantastical analogy for a present political misery—but right up next to it, unexpectedly, was the intimate, the bathetic, the comic:

Advertisement

[She] went back to rolling the joint, twisting one end into a little hat. She took out her lighter and set the little hat on fire. Watching the slow, dark burn gave me a tingle on my cock, which I put out with a scratch.

The girl in question is Mona May and she’s impossible. The narrator is a young man in a failing state but he is also just a kid in love with a (slightly older) woman who happens to drive him up the wall: “I looked at my face in the mirror, and asked myself a serious question: what am I doing here? If I could put up with her arrogance, her stupidity, her hallucinations, her mid-life crisis…what should I expect in return? At the very least, if I loved her, was still obsessed with her, then there was no reason for me to be here, since my presence clearly causes some kind of disturbance in her world.” Angst! Romance! Sex! Dicks! And illustrations, though these I could not see in the PDF, and had to content myself instead with the tantalizing captions. (“The leftover particles of shit that stuck to our bodies resulted in certain deformities. Marital relations suffered, and many died.”) Using Life is a riotous novel about a failing state, a corrupt city, a hypocritical authority, but it is also about tequila shots and getting laid and smoking weed with your infuriating girlfriend and debating whether rock music died in the Seventies and if Quentin Tarantino is a genius or a fraud. It’s a young man’s book. A young man whose youth is colliding with a dark moment in history.

In an attempt to draw more attention to Naji’s cause, Mona recently translated three very short, flash-fiction type stories for PEN’s website. They published one, “The Plant,” which begins like this:

I will not come through the door or the window,

but as a plant you cannot notice with your naked eye.

I will grow day after day, to the sound of your singing and the rhythm of your breath at night. A small plant you will not notice at first, growing beneath your bed.

From door to bed, to bathroom to closet, standing or sitting against the mirror. Through all these acts, and to the sound of your humming, I will grow. A small green plant. With grand slim leaves sneaking out from beneath your bed.

I read this voice first as the spirit of underground resistance, then as the essence of pervasive dictatorship, and then back to resistance once more. The second story, unpublished, was called “Ambulance” and began like so: “She was sucking my dick when suddenly she stopped to ask if I had given grandmother her medicine.” The last, also unpublished, was called “Normal,” and it opened this way: “One time as I was heading back to Sixth of October city, a prostitute showed up on the way dressed in the official uniform, a black cloak without a headscarf, and instead she had bangs and black hair falling over her shoulders. She was carrying a huge neon bag.”

Mona seemed a little perplexed that PEN had chosen only one of these shorts, but I could understand it. An imprisoned writer is a very serious thing indeed and should not be treated lightly, so it puts an activist in a certain sort of bind when the writer in question turns out to be lightness itself. Naji’s prose explicitly confronts what happens when one’s fundamentally unserious, oversexed youth dovetails with an authoritarian, utterly self-serious regime that is in the process of tearing itself apart. It’s very bad historical luck—of the kind I’ve never suffered. It’s monstrous. It’s ludicrous.

But the fact that the punishment does not fit the crime—that prison is, at this moment in Cairo, the absurd response to the word “pussy”—is exactly what shouldn’t be elided. In another historical moment, or so it occurs to me, young Ahmed would be at that PEN dinner, sitting right next to me, having come over from Cairo for a quick jaunt to see writer friends in Bed-Stuy, and he’d be a bit bored by the solemn speeches, sneaking out the back of the museum to smoke a joint perhaps, and then returning to his seat in high humor just in time to watch a literary giant whom he didn’t really respect come up to the stage to receive an award. That, anyway, is the spirit I detect in his novel: perverse and brilliant, full of youth, energy, light! Some writers, in the face of state oppression, will write like Solzhenitsyn. Others, like Naji, find their kindred spirits in the likes of Nabokov and Milan Kundera, writers who maintained their instinct for unbearable lightness and pleasure, for sex and romance, for perversity and delight, in the face of so much po-faced violent philistinism.

Advertisement

“I think I understand now,” writes Naji, in Using Life, “that the bullshit inside of us is nothing but a reflection of the bullshit outside. Or maybe it’s the other way round. In either case, the outside bullshit eventually seeps inside, and settles into the depths of our souls.” But on the evidence of his own writing the bullshit has not yet settled in Naji, not even in his jail cell. He is part of a great creative renaissance in Cairo, of young novelists and poets, graphic novelists, and—perhaps most visibly—graffiti artists, who have turned the city’s ever increasing walls into a staging site for political protest and artistic expression. Since 2014, President Sisi has cracked down on this community, with new restrictions on the press and multiplying arrests of artists and writers, and yet the Egyptian constitution guarantees both artistic freedom and freedom of expression. Naji has been prosecuted instead on Article 178 of the Penal Code, which criminalizes “content that violates public morals.”

An attempt to appeal was rejected in February. Naji’s last appeal is on December 4. If you read this and feel so moved, tweet #FreeNaji and any other social media action that occurs to you. Hundreds of Egyptian artists and intellectuals have signed a petition in support of Naji but there are also loud voices who feel that his example should not be used in a “freedom of literature” argument because they see his writing as not really literature, as fundamentally unserious. Using Life is certainly comic, sexual, wild—the work of an outrageous young man. We should defend his freedom to be so. “Falling in love in Cairo,” I learn, from his novel, “You have to prepare for the worst. You just can’t walk over to her and say, ‘Mona May, I’ve got the jones for you.’ Words like these could get a man hurt.” Over here, in New York, words won’t get you into too much trouble—not yet, anyway. What would we dare to write if they did?

Editor’s note: Ahmed Naji was released from prison on December 22, after Egypt’s highest appeals court temporarily suspended his sentence; a hearing will be held on January 1 to determine whether he will face another trial or be sent back to prison.

Ahmed Naji’s novel Using Life, in an English translation by Ben Koerber, will be published by The Center for Middle Eastern Studies (CMES) at The University of Texas at Austin next year.