Every few years, it seems, conservative religious groups, quiescent or unnoticed, come blazing back onto the national scene, and the secular press reacts like the bad guy in the 1971 western Big Jake who says to John Wayne, “I thought you were dead.” Wayne drily answers, “Not hardly.” Now, in The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America, Frances FitzGerald answers the recurrent question, “Where did these people [mainly right-wing zealots] come from?” She says there is no mystery involved. They were always here. We were just not looking at them. What repeatedly makes us look again is what she is here to tell us.

“Evangelicals” is an elastic term, and FitzGerald intermittently shrinks or stretches it. But she does direct us to the right starting point, to the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Great Awakenings, major religious events in our early history when the word “evangelicalism” came into wide American use. Evangelical religion is revival religion, that of emotional contagion. It can best be characterized, for taxonomic purposes, by three things: crowds, drama, and cycles.

Crowds

The first Great Awakening, of the 1730s and 1740s, stunned entire regions by the numbers of people who took part. The leading preacher in a cadre of them, George Whitefield—who, with John and Charles Wesley, founded the Methodist movement in England—had followings that overflowed the churches and followed him out to streets, plazas, or the nearby countryside. When Benjamin Franklin went to hear Whitefield preach from the steps of Philadelphia’s City Hall in 1739, he measured with characteristic precision the reach of his voice in different directions, and felt that he had verified reports that 25,000 people could hear him preach in a cleared space.

Before he came from England, Whitefield had already become a “field preacher”; the skeptic David Hume, who listened to one of his sermons in Edinburgh, is said to have told a friend, “He is…the most ingenious preacher I ever heard. It is worth while to go twenty miles to hear him.” Any man who could astonish Hume in Scotland and Franklin in America was a preacher beyond any orbit of expectation. The great Samuel Johnson said of Whitefield, “He would be followed by crowds were he to wear a night-cap in the pulpit, or were he to preach from a tree.”

The crowds were astounding because they were self-assembled, gathered outside the normal parish structures. This was nothing like going to one’s church on Sunday. It was an event. It could happen any day, and run for several days. It was symbolically important for the people to be “going out”—an exodus from the ordinary, including the ordinary religious formalities (ordained ministers, ecclesiastical garb, liturgical ceremony, a reverent hush in the congregation). It was salvation in a hurry, time was running out, too urgent for formal rites. The crowd was important to the whole ethos of the movement. The preacher was credentialed not by church authorities but by the size of his crowd and its responses to him—by the number of souls he saved.

Emotion was communicable. Salvation was catching. The Holy Spirit’s urging made for responses like “Amen,” or “Hallelujah,” or “Come Lord Jesus,” or “Glory!”—or the later “Praise the Lord.” Spasmodic seizures of different sorts made outsiders call the saved ones “holy rollers” or “quakers” or “shakers” or “jumpers.” The people would “turn, turn, turn,” as in the song “Simple Gifts.” Some would faint, “slain in the spirit.” The preacher himself could get worked up to pitches of near hysteria. The religious convulsions Whitefield and Wesley had inspired in England were called by Ronald Knox “Methodist paroxysms.” These spasms traveled well to America.

As the American West opened up, “going out” took on further meaning in the camp meetings or tent revivals of preachers like Barton Stone, Alexander Campbell, and their epigones. Stone’s weeklong revival at Cane Ridge, Kentucky, in 1801 drew a likely 20,000 people, over 10 percent of the state population. Dozens of preachers ministered to the people at Cane Ridge—including Presbyterians like Stone as well as some Baptists and (especially) Methodists. Revivals broke free not only of church buildings but of denominational divisions, creeds, and rituals. Huckleberry Finn went to a Campbellite revival:

There was as much as a thousand people there, from twenty mile around. The woods was full of teams and wagons, hitched everywhere, feeding out of the wagon troughs and stomping to keep off the flies…. Then the preacher begun to preach; and begun in earnest, too; and went weaving first to one side of the platform and then the other and then a leaning down over the front of it, with his arms and his body going all the time, and shouting his words out with all his might; and every now and then he would hold up his Bible and spread it open, and kind of pass it around this way and that, shouting, “It’s the brazen serpent in the wilderness! Look upon it and live!” And people would shout out, “Glory!—A-a-men!” And so he went on, and the people groaning and crying and saying amen.

Mark Twain had personal dealings with Alexander Campbell, since as a boy printer he had set some of his writings in type. (Franklin had done the same thing for Whitefield a century earlier.)

Advertisement

Such crowds could not stay outside in all weathers, so big halls were thrown up to hold them, beginning with one Whitefield quickly raised in Philadelphia. These were no ordinary churches. In Whitefield’s England, those who dissented from the established religion—the “non-conformists”—were said to worship in chapel, not church. Whitefield’s meeting house was a huge “chapel” in that sense, and so are evangelical buildings, right down to the megachurches of our day, places like Second Baptist in Houston, with 26,659 attending, or Saddleback Valley in California, with 22,055. Crowds are still essential, and at times they can go outside, as when Billy Graham filled a football stadium at the University of Tennessee in 1970 or gathered over a million people in the People’s Plaza of Seoul in 1973.

The outdoor venues of evangelicals had created “the sawdust trail” that people would file down to show they were saved, to make their own profession of faith, to shake the preacher’s hand, or to sign up for a local church. The sawdust aisles in tents were kept in the temporary structures specially built for revivals, and the term would be kept even in permanent structures. The evangelist preacher Billy Sunday (1862–1935) always called on the saved to “hit the sawdust trail,” no matter what hall he was in (if any).

An important evangelical success was the creation of virtual crowds for radio or television “gospel hours.” Something like the revivals’ shared responses can be elicited at a remove, making “crowd” a psychological category, not merely an arithmetical one. This is partly done by having live audiences present at the broadcasting site. This on-site audience, heated by a skilled preacher, serves as a surrogate for the larger but thinner population listening in.

But even without an immediate physical audience, the feel of a revival can be cultivated, often with the help of inspiring music. Participation can be stimulated (or simulated) by calls to the remote audience for prayer, by the naming of illnesses to be cured, by other kinds of virtual attendance. Holy mementos are offered for sale; prayers are directed to local needs. Even the constant pleas for money need not be merely venal. They allow the listeners or watchers to join the “ministry.” It is a way for the audience to make a declaration for Christ, to take action—mentally to “hit the sawdust trail.”

The more successful radio and TV revivals could boast of huge crowds knit together electronically. Popular preachers even created their own networks—CBN (Pat Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network), TBN (Paul Crouch’s Trinity Broadcasting Network), PTL (Jim and Tammy Bakker’s Praise the Lord network). By the mid-1980s, only two secular networks were larger than Robertson’s CBN.

Drama

The awakenings were crowd events, with controlled (if sometimes barely) excitement. They exemplify what Ronald Knox called the religion of enthusiasm. The urgency to be saved at once, with a flood of relief at such a rescue, comes from an awareness that the end is near. History for evangelicals keeps an exigent timetable. It is a theological equivalent to the Doomsday Clock tended by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The evangelical acceptance of the creationist doctrine that the universe began a “short time” ago and will not last long comes not only because “the Bible tells me so,” but as a reminder that history is compressed, that it is speeding along to its climax. One cannot put off the accounting for one’s soul. Be saved now or you are probably damned. Only accepting Jesus as your personal savior can give you a sure ticket to heaven. The impending battle of Armageddon can fill every moment of the believer’s life with drama. Any moment we may leap out of time straight into eternity.

To walk down toward a revival’s preacher, to make one’s decision for Christ, is a dramatic moment not only for the ones doing the deciding but for the onlookers, who are internally cheering them across the finish line to salvation. The great revivalist Charles Grandison Finney (1792–1875) knew how to increase this urge of people to save others. He created the “anxious seat” at his revivals, for those still hesitating to commit themselves to Jesus. Anyone in the anxious seat became the instant target of all the circumambient prayers. If the prayers successfully dislodged any of those seated, whoops of joy would greet another victory for the Holy Spirit.

Advertisement

Those who wrote the New Testament believed the world would end in their lifetime. This became something of an embarrassment when the church survived for years, and then for centuries. In the fifth century, Augustine of Hippo solved that problem with symbolic readings of the apocalyptic passages, saying they did not refer to literal time on the calendar. Thus the Middle Ages—with a few exceptions like the Joachite prophecies in the second millennium—lived with the everyday, not the final crisis.

That was changed during the Reformation, when the scarlet woman riding the seven-headed beast (Revelation 17.3–6) was interpreted as the pope on Rome’s seven hills, and the slaying of that beast was thought to be imminent. Protestants were apocalyptists, which made Americans super-Protestants, since they had split from the tainted English Protestants who retained bishops and priests, canons and deans.

The American Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) counted every defeat of Catholic forces around the world as a harbinger of history’s quick fulfillment. He organized prayer brigades to ensure specific Protestant victories, including a fast day for the British capture of the French fortress of Louisbourg in Canada. Benjamin Franklin mocked this cannonade by orison:

You have a fast and prayer day for that purpose; in which I compute five hundred thousand petitions were offered up to the same effect in New England, which added to the petitions of every family morning and evening, multiplied by the number of days since January 25th, make forty-five millions of prayers; which, set against the prayers of a few priests in the garrison, to the Virgin Mary, give a vast balance in your favor…. I believe there is a Scripture in what I have wrote, but I cannot adorn the margin with quotations, having a bad memory, and no Concordance at hand.

Edwards believed in a more optimistic chiliasm than that of later evangelicals. He agreed with John Winthrop (1588–1649) that Americans had come to a virgin continent to set up “a light upon a hill,” a model for the impending biblical millennium, the thousand-year reign of Christ mentioned at Revelation 20.2–5. These “postmillennials” think the world will end only after this thousand years of godly time, whose foundations were already being laid on American soil.

Opposed to such postmillennials are the premillennials, who think the world’s showdown battle (Armageddon) will happen before the thousand-year reign of Christ. The view that the saved will be snatched up to heaven (the Rapture) before the battle, given a sharper definition in England by John Nelson Darby (1800–1882), was promulgated in America by Cyrus I. Scofield (1843–1921) in his perennially best-selling Scofield Reference Bible. Debate on the religious right was waged between “premils” and “postmils” (in Protestant seminary slang). It was such debate, combined with different Calvinist views of predestination, that Huck Finn heard from church folk and muddled up as “preforeordestination.”

Most modern evangelicals are premils. They leave the postmil attitude to “mainline” churches, where work for godly goals can take the form of progress, social justice, and the benefits of science. Evangelicals, distinguishing themselves from most ritualistic churches, note with satisfaction that the influence of “mainline” churches has been dwindling. Secular forces of progress and science need no reinforcement from such an acquiescent religiosity. A worldly church is just the world, according to evangelicals. The salt has lost its savor.

Evangelicals want sudden rescue, linked with sudden judgment. Religion for them is an experience, not an argument. Emotional immediacy is treasured over everyday “improvement.” You do not improve your way into heaven. There is no moral evolution along the sawdust trail. You “hit it,” as Billy Sunday said, or you don’t. The appeal of a “premil” End Time to evangelical believers attracted notice in the 1970s when Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth outsold (with 81 million copies) other books of that era, including All the President’s Men, Roots, and The Joy of Sex.

Cycles

People have been right to ask, at intervals, where evangelicals have suddenly come from. They do seem repeatedly to disappear, only to reemerge unexpectedly. The price of intense emotional ebullition is burnout. The improvisings of the revival lack, at first, the forms and procedures of the institutional, which make for stability and continuity. It is hard to keep End Time piety at white heat, and even harder to keep outsiders interested. But relapses into a quieter life have never meant that believers stopped believing. They just continued to share their emotion around less conspicuous campfires. Max Weber would say their charisma undergoes routinization (Veralltäglichung). But the remission need not be permanent. Various crises, real or perceived, make the apocalypse plausible again.

This cyclic pattern of flarings and fadings was demonstrated spectacularly in the first Great Awakening. If you looked at America early in the eighteenth century, you would conclude that this was a country of fervid religiosity. If you looked at it at the end of the century, you would say it was a country of Enlightenment rationality, the country of our Founders and their documents. The evangelical scholar Mark Noll shows that the Great Awakening was followed by a Great Unchurching—the years 1750 to 1790 saw the deepest decline (in fact the only real decline) in Americans’ evangelical belief.* But what followed, with the dawn of the nineteenth century, was the second Great Awakening, the revival of revivalism. The rhythm is peristaltic. In 1925, most learned Americans thought that Clarence Darrow and H.L. Mencken had, between them, slain all opposition to Darwin at the Scopes trial. But evangelicals were simply gathering strength to mount ever-newer defenses of what they now call “creation science.”

It was easy for some evangelicals to go into hibernation mode, since some of them have always been leery of engagement with “the world.” These separatists do not want to be sullied with compromise. Carl McIntire (1906–2002), the prolific author and radio preacher (and proponent of rebuilding Noah’s ark to ride away from a damned world), wrote that the proper response to nonbelievers is “attacks, personal attacks, even violent attacks.” Jerry Falwell (1933–2007), before he founded the evangelist Moral Majority to engage in politics, had been a separatist, saying believers should not waste their time on passing worldly concerns like anticommunism or civil rights. But separatists are usually ready to come out of their cave when they find the world willing to listen to them. (McIntire, for instance, mounted a full-throated defense of the war in Vietnam.)

Sometimes this involves finding allies for causes they espouse—as evangelicals found labor unions would join them in the Sabbatarian ban on delivering mail on Sundays (passed into law in 1912), or when early feminists helped them prohibit alcohol (by the Eighteenth Amendment of 1919). FitzGerald identifies evil occasions that have mobilized modern evangelicals in response—as when Billy Graham discovered “godless” communism (as the foe of religion), or Anita Bryant discovered homosexuality (as being inculcated), or Phyllis Schlafly discovered feminism (ready to draft women into the armed forces), or Francis Schaeffer discovered “secular humanism” (as the death rattle of the West), or Jerry Falwell discovered abortion (as murder). Steve Bannon’s discovery of Islam as the main threat to America came a little too late for FitzGerald to include, but it has picked up heavy support among the evangelicals she is describing.

Issues like these become, for a time, matters that even the less godly may get concerned about. This can give the more fervent evangelicals a giddy sense of acceptance. In 1979, the year Jerry Falwell founded the Moral Majority, the television faith healer Pat Robertson effused: “We have, together with the Protestants and the Catholics, enough votes to run the country. And when the people say, ‘We’ve had enough,’ we are going to take over.” Falwell himself hoped to add conservative Jews to the ranks, and said, “We are fighting a holy war, and this time we are going to win.”

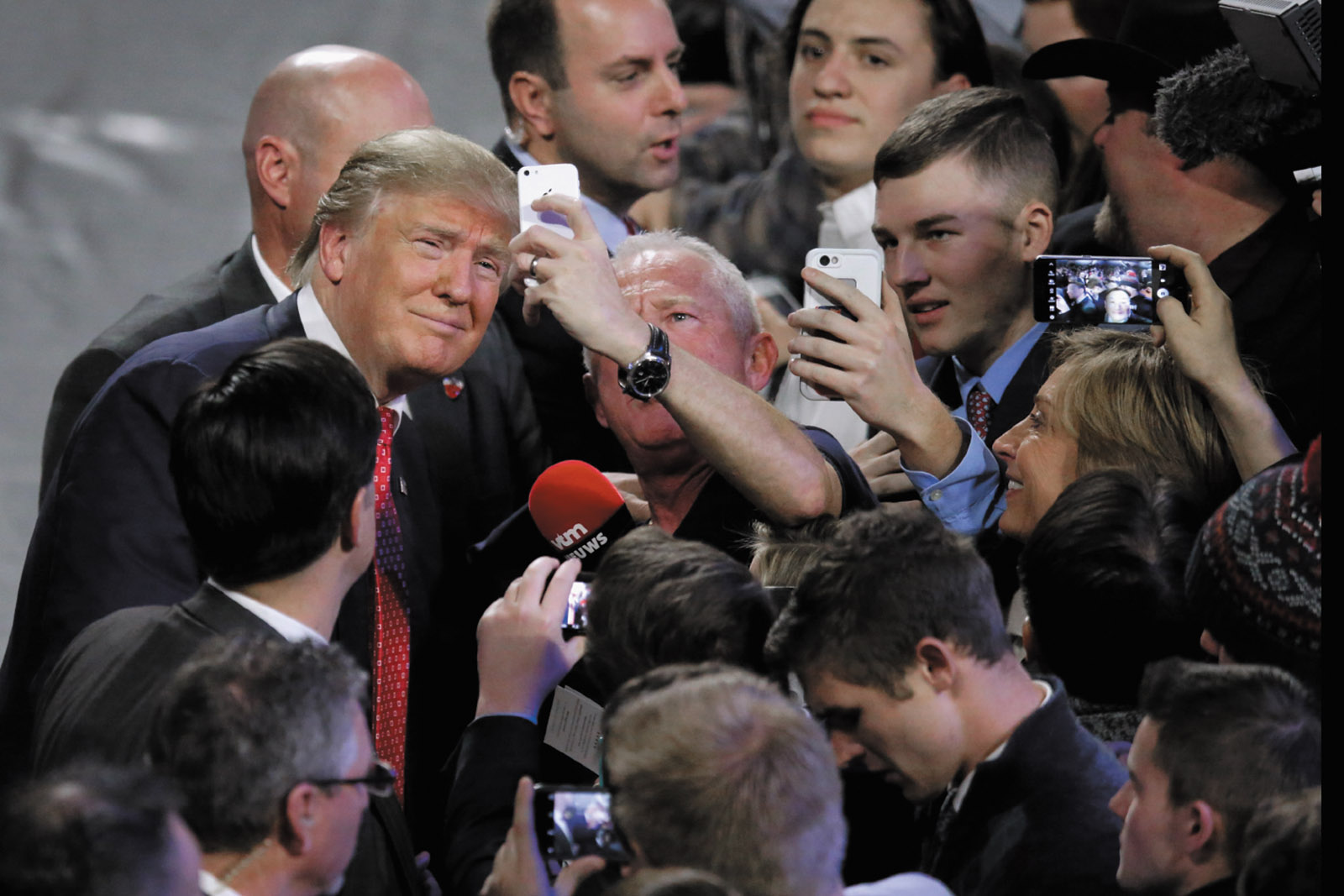

Recently we have had other such flashpoints—over “religious freedom” (the right to discriminate on religious grounds against other people’s constitutional rights), or same-sex marriage, or transgenderism. But the most successful current issue has been the opposition to abortion—FitzGerald notes that state legislatures have passed or proposed three hundred bills to limit access to abortion between 2011 and 2016. The hope of repealing Roe v. Wade with a new Supreme Court justice helped prompt 81 percent of evangelicals to vote in 2016 for an irreligious lecher as president.

FitzGerald is good at describing these high-profile engagements in The Evangelicals. She observes the niceties that divide different factions in the biblical camp. She notes that some of the people she calls evangelicals don’t want to be called that. Fundamentalists don’t necessarily support the religious right. Certain Pentecostalists don’t want to be confused with Charismatics, and vice versa. Southern Baptists veer off in different directions under different leaders. By trying to preserve a diplomatic objectivity as an observer, FitzGerald has to confess that “this book is not a taxonomy.” She nonetheless uses “evangelical” as a conveniently vague term for most kinds of revivalism, while diplomatically recognizing even small-bore turf battles.

But she makes one astounding error of taxonomy. She doesn’t include black churches in a study of evangelicals. She “omits the history of African American churches” because “their religious traditions are not the same as those of white evangelicals.” Who are these white evangelicals she is talking about? Some white evangelicals were abolitionists while others were defending slavery. It is hard to deny that many if not most black churches are evangelical in style. They have preachers credentialed by enthusiastic congregations, outcries during the sermon (“Tell it!”), proclamatory music, and cyclic intensities.

In fact, in an earlier book, Cities on a Hill (1981), a study of four different “visionary communities” in America, FitzGerald said that preachers like Martin Luther King Jr. gave Jerry Falwell warrant to give up his own earlier separatism as “false prophecy.” Many black churches have agreed with white evangelicals in condemning abortion and homosexuality. There are black religious conservatives as well as liberals, or a mix of both. There have been hugely successful outliers like Father Divine (1876–1965) and Reverend Ike (1935–2009) whom it would be misleading to label as simply conservative or simply liberal; but they were certainly evangelical.

Reverend Ike called his following “the do-it-yourself” church, and the whole evangelical enterprise could adopt that as a slogan. Evangelicalism is a bottom-up religiosity as opposed to a top-down one. It prefers the improvised over the prescribed, spontaneity over tradition, experience over expertise, emotion over slower religious reasonings. Ronald Knox said, “The Evangelical is always an experimentalist.” Evangelicals are suspicious of establishment, liturgy, elaborated creeds, and standardized piety.

Evangelicalism tends to break out of any single denomination—think of the preachers from various bodies at Cane Ridge. It is fissiparous even in its most favorable environments—think of Methodism branching into the Disciples of Christ, the Holiness Movement, the African Methodist Episcopal Church. (Whitefield, it should be remembered, was an ordained Anglican.) Evangelicalism is a style—Mark Noll calls it a “value system.” It can affect even some “high church” bodies or members. There are Pentecostalists among Roman Catholics. (Phyllis Schlafly, it should be remembered, was a Catholic, as Kellyanne Conway and Steve Bannon are. Bannon showed his allegiance in his 2014 Skype address to the Institute for Human Dignity at the Vatican.)

Given this description of evangelical style, two things should be noticed. America is, or likes to think of itself as, a “do-it-yourself democracy.” Many of the traits I have been listing are ones Americans will fancy themselves as embodying (or wanting to). People who hit the sawdust trail are working a kind of do-it-yourself salvation. The credentialing by the people is what all presidents claim. No wonder Noll thinks of evangelical religion (despite its roots in Wesley’s England) as native to America, as giving America its most recognizable God. Calvin said God “elects” his chosen ones. In America we choose to elect our leaders. The crowd credentials the preacher. Historians rightly observe that our national political conventions have borrowed elements from revivals.

A second thing to notice is how many of the traits I have listed would be ascribed by his voters to Donald Trump. He too presented himself as opposed to elites, to the academic and political and journalistic establishments, even (for a brief lying while) to banks and special-interest lobbying. He is spontaneous and improvising—“telling it like it is” in his supporters’ eyes. He feels so credentialed by his crowds that he cannot even conceive that more people voted for the establishment candidate than for his own “authentic” ticket—he will no doubt go to his grave thinking that any votes against him were rigged.

Trump has a style that seems like no style to the “proper” viewer, the “politically correct.” His antiestablishment pose could not, all by itself, make 81 percent of evangelicals vote for him. They had ancillary reasons for doing that—the hope of outlawing abortion, Hillary hate, feeling scorned by “the elite.” But his style helped ease the godly toward this godless man. They felt he was “talking their language”—little realizing that it was the language of Father Divine among others, of evangelicals as tastelessly rich as Donald Trump. It is the “tastelessly” that assures them he is no snob. As Fran Lebowitz says, “He’s a poor person’s idea of a rich person”—living in a vulgar gold splendor the poor man would embrace if he had “made it.”

Trumpian populism has proved a natural fit for Steve Bannon. The films he produced celebrate populist heroes—Sarah Palin (The Undefeated, 2011), “Duck Commander” Phil Robertson (Torchbearer, 2016)—or they let spokespersons like Dick Morris, Mike Flynn, and John Bolton denounce the “elites” of the establishment—The Battle for America (2010), Generation Zero (2010), Clinton Cash (2016). Bannon even has his own version of the evangelicals’ Armageddon, one that explains the dark message of Trump’s inaugural “American carnage” speech that he worked on. Ronald Radosh says that Bannon told him, “I’m a Leninist. Lenin wanted to destroy the state, and that’s my goal too. I want to bring everything crashing down, and destroy all of today’s establishment.”

That is not quite true. Bannon thinks the establishment is crumbling on its own, which is why Trump calls everything preceding his glorious arrival a “disaster.” In Generation Zero Bannon said that a cataclysm is already in process. In two books he admires and promotes, and on which he based Generation Zero, two amateur historians, William Strauss and Neil Howe, argued that each country gets four cataclysmic “turnings” when the status quo falls apart and a new order has to be invented or imposed. America has used up three of its turnings (the Revolution, the Civil War, the Great Depression) and its last has already begun. “The end is near.” No wonder Trump can disregard experts in places like the State Department—their demise is being taken care of by history.

Trump has been accused of being drawn to Alex Jones–style conspiratorial theories. Bannon assures him it is something grander than that. They are instruments of a great historical destiny. A do-it-yourself politics like the do-it-yourself religion of the evangelicals is the only thing to rely on in the crash of our ultimate turning. It looks less and less odd that 81 percent of evangelicals voted for Trump. They know what End Time sermons look like.

Given these apocalyptic developments in the time between FitzGerald’s finishing her book and its publication, there is a certain wry poignancy to her final pages. She drops hints (hopes?) that the cycle of periodic revivals may have finally exhausted itself. She says that the evangelicals’ numbers are declining, that they no longer have national leaders or organization. Millennials, “the largest of all living generations,” are not drawn to their preachers. Does that mean that we may not have to ask, in the future, “Where did these people come from”?

Not hardly.

This Issue

April 20, 2017

Invisible Manipulators of Your Mind

Secret Knowledge—or a Hoax?

-

*

See Mark A. Noll, America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln (Oxford University Press, 2002). ↩