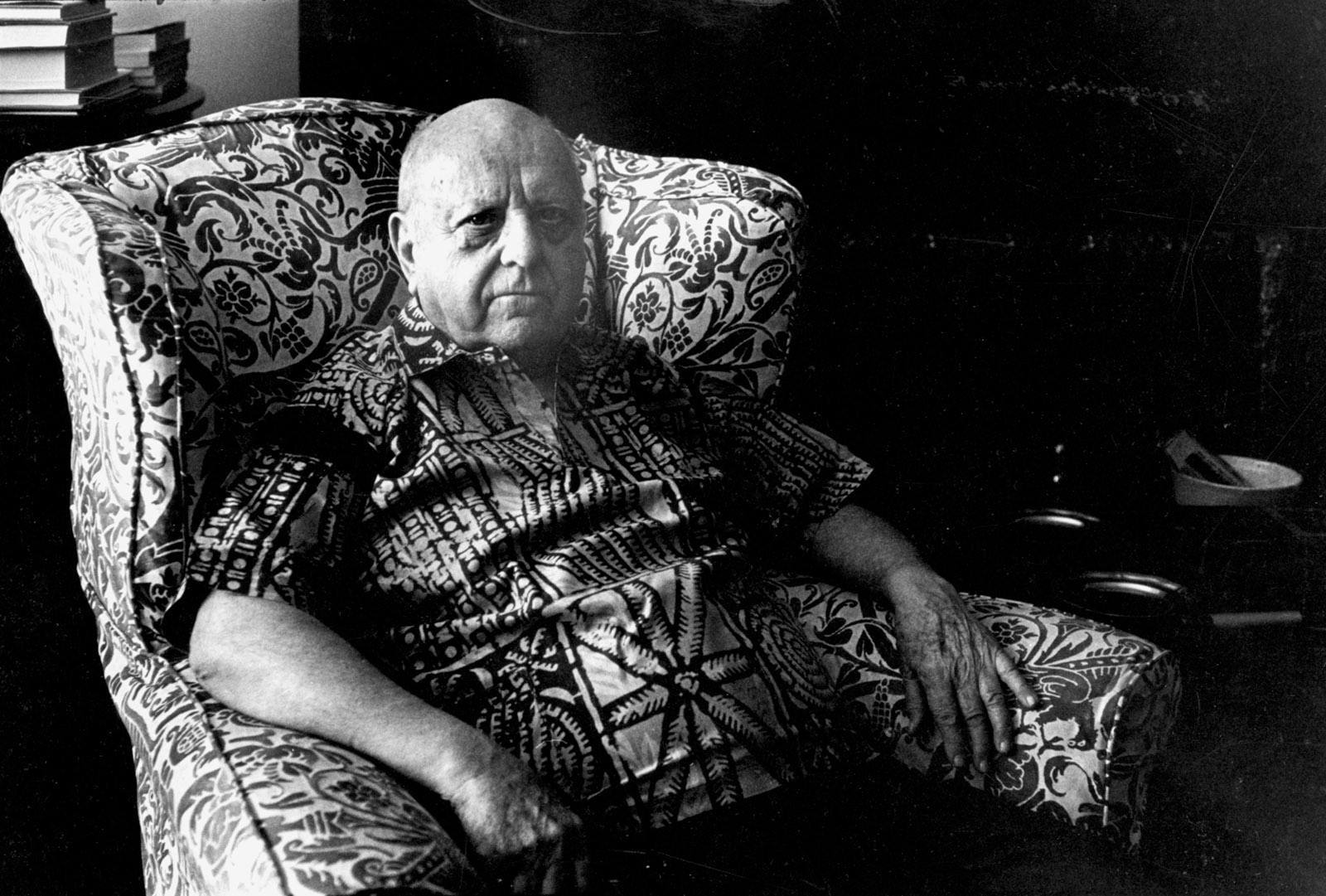

In 1942 the composer Ned Rorem, then nineteen, attended a panel at Northwestern University made up of various grandees from the world of music. One of them—a short, stocky bald man with a high-pitched voice and a face like an owl—was Virgil Thomson, a composer and the chief classical music critic for the New York Herald Tribune. The panel, as Rorem remembered it, began with an attempt to define music:

The others were falling back on Shakespeare’s “concord of sweet sounds” when Thomson shrieked: “Boy, was he wrong! You might as well call painting a juxtaposition of pretty colors, or poems a succession of lovely words. What is music? Why, it’s what we musicians do.”

The story captures some of what makes Thomson’s music writing at once so admirable and so maddening. At its best, his criticism was disarmingly direct and unpretentious. He could write with style, and had a knack for bringing the sound of music to life, as when he described the finale of the Brahms Third Symphony, “where the winds play sustained harmonic progressions which the violins caress with almost inaudible tendrils of sound, little wiggly figures that dart like silent goldfish around a rock.” He was a fierce advocate of styles of music that were dismissed as quaint and unimportant or ignored entirely, especially French music, such as the works of Debussy, Ravel, Poulenc, and Satie, and new music by living American composers. Most of all he had a willingness to speak his mind even when it meant contradicting the press, the concert-going public, and the administrations who ran the orchestras.

But he was hardly a model critic. He gave friends positive reviews, enemies negative reviews, and usually made sure his own music was reviewed by a stringer (occasionally he did it himself). He routinely slept through performances he was reviewing, had a penchant for making sweeping and sometimes perplexing generalizations, and dismissed beloved works and composers with little explanation, which made him seem at times like a dyspeptic, irascible crank.

Many of his musical opinions—often deeply idiosyncratic—have not aged well (he hated Sibelius, didn’t particularly like Wagner, was lukewarm on Gershwin, and considered Ives a minor composer). These views were generally of a piece with his music, which was modest and tonal and heavily Francophile, drawing especially on the work of Satie, medieval sacred music, and American hymns and folksongs. In fact he considered himself a composer who wrote music criticism and did so because, in his words, “I thought that perhaps my presence in a post so prominent might stimulate the performance of my works.”

Yet by the time he left the Herald Tribune in 1954, his provocations had changed the American classical music world for the better: in particular there were more performances by living composers, especially Americans. Two volumes from the Library of America, Music Chronicles: 1940–1954 and The State of Music and Other Writings—the first a collection of his criticism from his years at the Herald Tribune, the second a miscellany of later writings, including his autobiography (alone worth the price of the book) and longer essays on music and the arts—capture Thomson’s remarkable life in writing.

Music was a part of his life almost from the beginning. He was born in 1896 in Kansas City, Missouri, and claimed to have learned to read music the same year he learned to read, when he was five. His parents, devout Baptists, brought him to services where he soaked up hymnody. Yet while the music moved him, he was never taken with religion itself, tending instead toward irony and urbanity. In his autobiography, Virgil Thomson (1966), he wrote admiringly of Missouri’s open vice, lavish hotels, theaters, and saloons. Of their alleged thousands of brothels Missourians “were no less proud…than of our grand houses, stone churches, and slums…and a political machine whose corruption was for nearly half a century an example to the nation.”

Thomson grew up during what he called “the Wild West’s own Indian summer and…the final flourishing of Victorian blood-and-thunder on the stage.” Like Ives, he listened not just to the classical repertory but to hymns, marches, and ragtime, all elements that he would later draw on in his own compositions. In the summer he heard the great American marching bands play outdoor concerts, including John Philip Sousa’s arrangements of Wagner for brass band, which he called “the most luscious harmonic experience that exists.”

Bullied as a child, Thomson took refuge in books, and by the time he reached junior college, he had developed what his friend Alice Smith remembered as a

faculty of pungent criticism, which he used freely on other class members…. His criticism was sometimes a little harsh, and was always delivered with a combination of omniscience and patronage that was hard to take; but it was usually just and well-deserved, and no one ever hesitated to take it.

The Smith family—descended from Joseph Smith, the founder of the Mormon church (Alice was his great-granddaughter)—would be important to Thomson, and not just when Alice’s testimony was all that saved him from being expelled from technical college for organizing a reading of obscene poetry at which impressionable young girls were present. Alice’s father, who gave Virgil peyote on the condition that he keep an itemized report of its effects on him, ultimately helped secure him a church fellowship that allowed him to attend Harvard in 1919.

Advertisement

At Harvard, Thomson, who had been playing the piano and organ, began to compose, and it was there that he discovered two guiding and lifelong interests: the work of Gertrude Stein, whom he would later meet in Paris, and the music of Erik Satie. Satie’s music was simple, small-scale, and quiet—the opposite of the Austro-German music (Wagner, Strauss, Brahms) then in vogue. There he also met Maurice Grosser, the painter, author, and art critic who would become his lifelong companion.1

In 1921, Thomson went on a tour of Europe with the Harvard glee club, and stayed on for a year afterward in Paris, living on a modest fellowship. In his letters—regrettably not included in these collections—he captures the allure of entre deux guerres Paris, describing in one the scene at Le Boeuf sur le Toit, a famed cabaret where a friend played jazz piano at night. It was, he wrote,

the rendez-vous of Jean Cocteau, Les Six, and les snobs intellectuels—a not unamusing place frequented by English upper-class bohemians, wealthy Americans, French aristocrats, lesbian novelists from Romania, Spanish princes, fashionable pederasts, modern literary & musical figures, pale and precious young men, and distinguished diplomats towing bright-eyed youths.

After graduation, Thomson lived in Paris until 1940, surviving variously on commissions, freelance music journalism, piano lessons, and the largesse of wealthy patrons. He was remarkably successful at inserting himself into the center of the city’s art world, and his weekly open houses, an article from The Yale University Library Gazette recalled, included guests like

André Gide, Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Henri Sauguet, Christian Bérard, Christian Dior, Gertrude Stein, and Alice B. Toklas, and might have featured fruit cake made in Kansas City by Thomson’s mother or a wine cup and paté from recipes of Miss Toklas.

By far the most important friendship he made in these years was with Stein. When the two met in 1926, Thomson so impressed her with his knowledge of her work that, as he left, she took him aside and said, “We’ll be seeing each other.” Later, Thomson wrote that “[Gertrude and I] got along like a couple of Harvard boys.” Soon the two were collaborating, with Thomson setting her texts to music, and by 1928 they had finished an opera, Four Saints in Three Acts.

The opera was quietly revolutionary. It used an all-black cast for serious roles rather than minstrelsy, and Stein’s libretto—perhaps unsurprisingly—focused almost entirely on the aural quality of the words, not concerning itself too much with narrative. (“Pigeons on the grass alas./Pigeons on the grass alas./Short longer grass short longer longer shorter yellow grass. Pigeons large pigeons on the shorter longer yellow grass alas pigeons on the grass.”) Thomson later wrote that her writing was “manna” for setting to music. With its shimmering sets made of Saran Wrap, Stein’s mesmeric nonsense language, and Thomson’s simple, repetitive diatonic music, it is hard not to think of his experiments with peyote.

The work’s premiere at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford in 1934 drew the cream of society and made Thomson’s reputation. Lucius Beebe, the Herald Tribune’s society columnist, described the scene:

Since the Whisky Rebellion and the Harvard butter riots there has never been anything like it, and until the heavens fall or Miss Stein makes sense there will never be anything like it again. By Rolls-Royce, by airplane, by Pullman compartment, and, for all we know, by especially designed Cartier pogo sticks, the smart set enthusiasts of the countryside converged on Hartford.

Wallace Stevens, also in attendance that night, disagreed about the smartness of the crowd, writing to a friend that there were “numerous asses of the first water in the audience…people who walked round with cigarette holders a foot long, and so on.” But the opera itself he found “most agreeable musically.” And though critical reception was mixed, the production traveled to Broadway, a triumph for a new opera and a delight for Thomson and Stein.

During the 1930s Thomson found work writing music for film and theater projects, many of them funded by the WPA. He composed scores for two documentaries and worked with Orson Welles, writing incidental music for a number of plays, one a production of Macbeth set in Haiti. Another, some years later, was a version of Shakespeare’s historical plays in which Welles, who in Thomson’s words “had by this time grown quite fat,” played Falstaff (this sequence of plays was the inspiration for Welles’s famous film Chimes at Midnight). But Thomson had to compete for the right to score it. He got the part, he recalled in his autobiography,

Advertisement

by taking Orson and his wife to a blowout at Sardi’s, with oysters and champagne, red meat and Burgundy, dessert and brandy, before [Welles] pulled himself into his canvas corset for playing Brutus. “You win,” he said. “The dinner did it. And it’s lucky I’m playing tragedy tonight, which needs no timing. Comedy would be difficult.”

Years of working in so many different parts of the world of music gave him insights into it that he drew on when he wrote The State of Music (1939), an entertaining if overgeneralized description of the classical music industry that includes a chapter titled “How Composers Eat, or, Who Does What to Whom and Who Gets Paid.” In the book’s most interesting sections, Thomson attacks what he called the music appreciation racket, focusing his ire particularly on record companies and radio stations that sponsored dubious forms of musical education in order to help sell recordings. In a complaint as resonant today as it was in 1939, he bemoaned the practice of what he called the “religious technique”:

Music is neither taught nor defined. It is preached. A certain limited repertory of pieces, ninety per cent of them a hundred years old, is assumed to contain most that the world has to offer of musical beauty and authority.

This method, in his mind, led to a kind of mindless veneration of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European symphonic music, and encouraged the idea that all classical music worth listening to had been written by someone dead.

The book caught the attention of Geoffrey Parsons, who oversaw the Herald Tribune’s arts coverage. He was looking to replace the paper’s recently deceased classical music critic, and as luck would have it, Thomson had just arrived in New York, having fled Paris in advance of the German invasion. Parsons offered him the job. It was a gamble—Thomson had no experience working at a newspaper—but one that ultimately paid off.

In his first review, he wrote on the New York Philharmonic’s season-opening concert. He didn’t spare anyone’s feelings, calling the orchestra’s performance “routine” and Sibelius’s Second Symphony “vulgar, self-indulgent and provincial beyond all description,” before concluding, “I understand now why the Philharmonic is not a part of New York’s intellectual life.” It was an effective shot across the bow at orchestras and critics whom he viewed as long since having fallen into complacency.

Rival critics tended to share the public’s taste for nineteenth-century symphonic works, and especially works by the three Bs—Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms. They also tended to limit their reviewing to performances at major concert halls by major orchestras (and, less often, opera companies). Unlike his competitors, Thomson went further afield.

In his first year, as he reminisces in his autobiography, he covered not just the major operas and orchestras but, among much else, student orchestras, swing concerts, Broadway musicals, and a production of Twelfth Night with music by Paul Bowles, whom he hired as a stringer at the Herald Tribune. For his Easter Sunday piece, he visited a church in Newark to review a performance by Brother Utah Smith, an electric guitar player who wore a blue sack suit with “a pair of white wings made of feathered paper and attached to his shoulders like a knapsack by crossed bands of white tape.” His goal as chief critic of the Herald Tribune, he said, could be summed up by a passage from his book, The State of Music:

To expose the philanthropic persons in control of our musical institutions for the amateurs they are, to reveal the manipulators of our musical distribution for the culturally retarded profit makers that indeed they are, and to support with all the power of my praise every artist, composer, group, or impresario whose relation to music was straightforward, by which I mean based only on music and the sound it makes.

True to his word, he took on the entrenched interests in the music world. In 1947, he published a series of articles attacking Arthur Judson, the powerful manager of the New York Philharmonic who also happened to be president of the Columbia Concerts Corporation, which arranged soloists for the Philharmonic—a tidy arrangement that allowed him to book his clients in major orchestral performances. Thomson also went after one of Judson’s favorite clients, the soprano Dorothy Maynor (“immature vocally and immature emotionally”). The Maynor review so enraged Columbia Concerts that it allegedly discussed withdrawing all advertising from the paper until Thomson was fired.

The most beloved performers were not immune. The violinist Jascha Heifetz he called a purveyor of “silk-underwear music,” a performer who “sacrifices everything to polish” and is known for his “justly remunerated mastery of the musical marshmallow.”

Even Toscanini didn’t escape. Though Thomson admired the conductor, he was infuriated by Toscanini’s insistence on playing only familiar classics and programming almost no contemporary music. It was a legitimate concern—Toscanini’s name was then as recognizable as Joe DiMaggio’s, and he could have done much to help introduce new composers to the millions of listeners who tuned in to his radio program. In a review written in 1942, Thomson takes the maestro to task:

Toscanini’s conducting style…is disembodied music and disembodied theater. It opens few vistas to the understanding of men and epochs; it produces a temporary, but intense, condition of purely auditory excitement. The Maestro is a man of music, nothing else. Being also a man of (in his formative years) predominantly theatrical experience, he reads all music in terms of its possible audience effect…. He quite shamelessly whips up the tempo and sacrifices clarity and ignores a basic rhythm, just making the music, like his baton, go round and round, if he finds his audience’s attention tending to waver. No piece has to mean anything specific; every piece has to provoke from its hearers a spontaneous vote of acceptance. This is what I call the “wow technique.”

Though he viewed himself, in his own words, as a species of knight errant, Thomson was not above using his post to settle old scores or pursue vendettas, or to actively promote his own work. As Anthony Tommasini, Thomson’s biographer, noted, orchestras that performed his music could generally count on his critical support. Not coincidentally, orchestras began making more and more requests for him to guest conduct, and commissioned more compositions from him.

Thomson retired from the Tribune in 1954, partly because of fatigue and looming boredom, and partly to devote more time to conducting and composing. Again, not coincidentally, as soon as he left the paper these requests dropped off. He would go on composing in his later years—including the opera Lord Byron, which prompted Andrew Porter to write that

like Purcell and Britten, Thomson has the gift to declaim English lines in melodies that not merely are fitting in rhythm and pitch inflections but make music in which words and musical contour seem indissolubly joined.

But his best works, like The Mother of Us All, his second opera with Gertrude Stein, were behind him.

In his later years, until his death in 1989, he was famous for his intellectually raucous (and expertly prepared) dinners in his room at the Chelsea Hotel, a bit of pre-war Paris preserved in Manhattan. He also continued to write books, reviews, and longer essays, many of them published in these pages. He wrote variously of old friends, like the producer John Houseman, whom he had worked with in the Federal Theatre Project in the 1930s and who went on to work with Welles on Citizen Kane, as well as of Gertrude Stein.

And he wrote about old friends turned enemies, like John Cage. The two had met in 1939, when the young Cage first wrote to Thomson soliciting compositions for his percussion group to play. By 1945 Thomson was calling him a “genius as a musician.” Thomson went on to help him find work as a stringer for the Herald Tribune and even nominated him for a Guggenheim. Then he commissioned Cage to write a book about him.

Things took a turn after Thomson read the first draft, which he found insufficiently appreciative of his music. So he dropped the project—not something Cage was particularly happy about—and then some years later brought in the musicologist Kathleen Hoover to write what would be the biographical half of a new, improved book, asking Cage to write only on the music. When the two turned in a new draft, Thomson—again piqued by Cage’s less than adoring assessment of his work—took a hatchet to it, in turn infuriating Cage, who had already been further antagonized by his discovery that he and Hoover couldn’t stand each other. The book, Virgil Thomson: His Life and Music, was finally published in 1959, as Robert Craft wrote, “not to wide acknowledgment or the approbation of its subject.”

Thomson and Cage’s friendship never quite recovered, and as Cage’s career flourished, Thomson grew jealous, finally taking revenge in 1970 with his essay “Cage and the Collage of Noises” (one of the works listed for review is Virgil Thomson: His Life and Music). In it, Thomson traces Cage’s development as a composer, from the prepared piano to unorthodox percussion ensembles to his aleatoric music that left notes, tempo, and even structure of compositions up to chance.2 In all of it Thomson sees a drive to destroy the history of music, an “inventor’s view of novelty” that Cage inherited from his father (who had invented, among other things, a diesel version of the submarine) and that “prizes innovation above all other qualities—a weighting of the values which gives to all of his judgments an authoritarian, almost a commercial aspect, as of a one-way tunnel leading only to the gadget-fair.”

It is hardly a generous assessment. Cage himself might have described his work more as an attempt to help listeners find what is alive and beautiful in the noises around them—but the review was so persuasive and engrossing that, according to Tommasini, even Cage’s friend and editor Minna Lederman failed when she first read it to realize that Thomson had, once again, written a hit piece.

-

1

Thomson doesn’t write about his homosexuality in any of his published works, but those interested in learning more about him, and particularly this part of his life, should consult Anthony Tommasini’s excellent and exhaustive biography, Virgil Thomson: Composer on the Aisle (Norton, 1997). ↩

-

2

The New York Review, April 23, 1970. ↩