Emily Raboteau

‘Know Your Rights!’; mural by Nelson Rivas, aka Cekis, Washington Heights, Upper Manhattan. Commissioned in 2009 by the People’s Justice for Community Control and Police Accountability, it has since been painted over. ‘The mural struck me as an act of love for the people who would pass it by,’ Emily Raboteau writes in her essay in The Fire This Time, and ‘as a kind of answer to the question that had been troubling us—how to inform our children about the harassment they might face.’

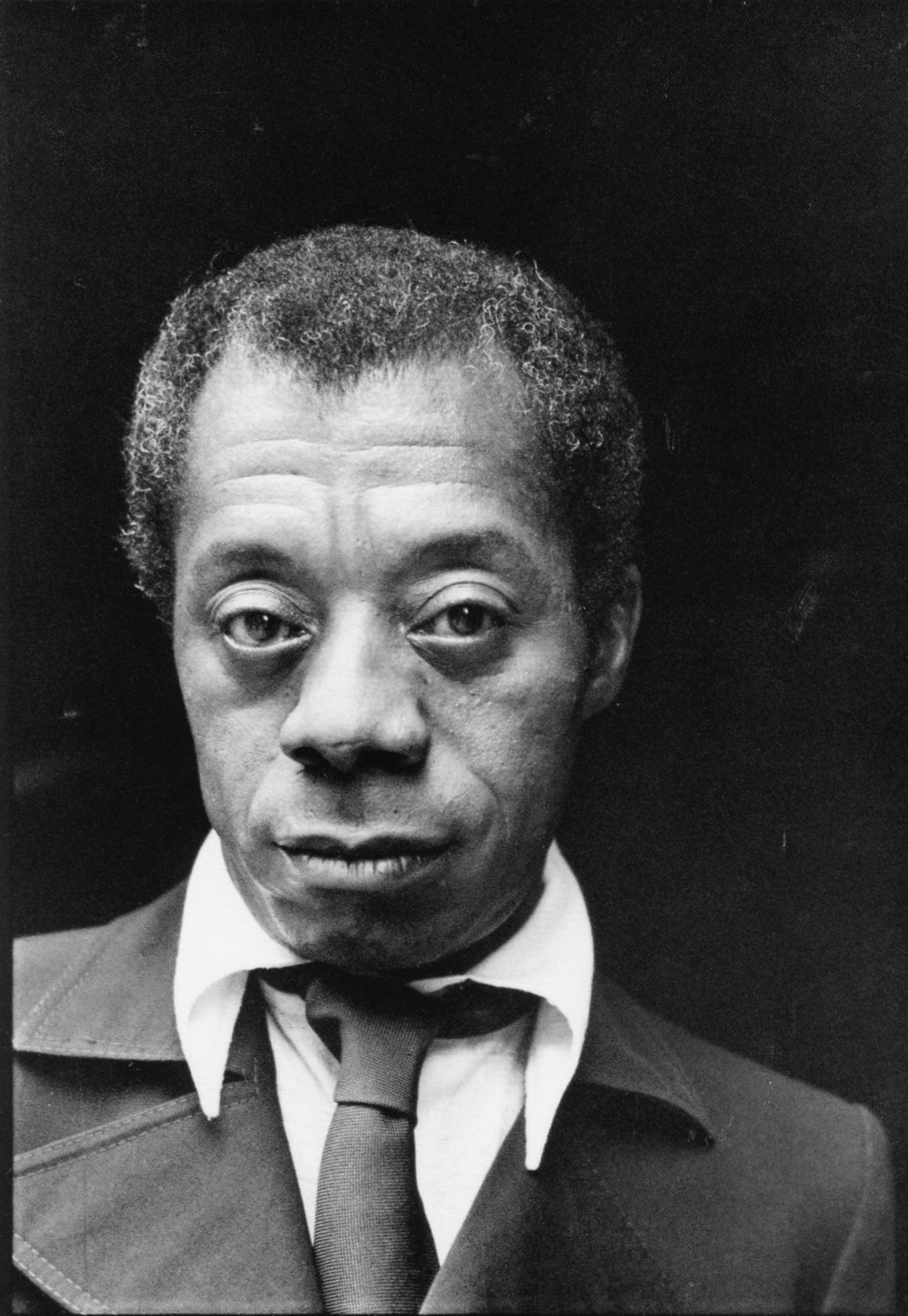

Writing about The Fire Next Time in the first issue of this paper in 1963, F. W. Dupee said that James Baldwin, at his best, illuminated not just a book or an author or an age, but a strain in the culture. However, in The Fire Next Time, with its incendiary title, he thought that Baldwin had given up analysis for exhortation, criticism for prophecy. Dupee regretted Baldwin’s sweeping generalities—that white people do not believe in death, for instance, or that white people are intimidated by black skin. Yet Baldwin impressed him as “the Negro in extremis, a virtuoso of ethnic suffering, defiance, and aspiration,” which at this distance, even as praise, begins to sound a little weird.

The Fire Next Time is composed of two essays, the brief “My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation,” which Dupee judged to be overly polemical, and the much longer “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” which he admired for its evocation of Harlem, Baldwin’s description of his flight as an adolescent into the pulpit, and his report on a visit with Elijah Muhammad at the Chicago headquarters of the Nation of Islam. Dupee trusted Baldwin when he had a concrete occasion for his reflections. But Baldwin’s “speculative fireworks” made him uneasy. Black Americans may have been ambivalent about being integrated into a burning house; nevertheless America was the only house they had, Dupee said.

We can’t get back to Dupee’s language, but maybe we can catch up to Baldwin’s. Remembering his surrender to God on a church floor, he wrote:

All I really remember is the pain, the unspeakable pain; it was as though I were yelling up to Heaven and Heaven would not hear me. And if Heaven would not hear me, if love could not descend from Heaven—to wash me, to make me clean—then utter disaster was my portion. Yes, it does indeed mean something—something unspeakable—to be born, in a white country, an Anglo-Teutonic, antisexual country, black. You very soon, without knowing it, give up all hope of communion. Black people, mainly, look down or look up but do not look at each other, not at you, and white people, mainly, look away. And the universe is simply a sounding drum; there is no way, no way whatever, so it seemed then and has sometimes seemed since, to get through a life, to love your wife and children, or your friends, or your mother and father, or to be loved. The universe, which is not merely the stars and the moon and the planets, flowers, grass, and trees, but other people, has evolved no terms for your existence, has made no room for you, and if love will not swing wide the gates, no other power will or can. And if one despairs—as who has not?—of human love, God’s love alone is left. But God—and I felt this even then, so long ago, on that tremendous floor, unwillingly—is white.

It was not as though existential loneliness and the black condition had been among what the Romantics called the previously unapprehended relations of things. Black writers were describing a living, unfolding history. While W.E.B. Du Bois was deep in his Communist phase, Richard Wright was the most eloquent black writer before Baldwin about political and social matters—more so than Ralph Ellison, though the fiction Wright was writing around the time Ellison produced his masterpiece Invisible Man (1952) was dreadful. Wright was living in Paris when he died in 1960, as the civil rights movement in America was intensifying. Baldwin inherited Wright’s themes and expanded on them, just as Wright had received his and added to them. Singular as they both were, Baldwin’s language could not have been Wright’s.

Toward the end of his life, Wright was seen as belonging to a bygone era, most notoriously by Baldwin himself, and Baldwin would be viewed similarly when he died twenty-seven years later. What is striking about the comparison between the two writers is not the fate of their reputations immediately after their deaths or over time, but that they both had been outspoken on race and both their writing lives happened to have ended during periods of conservative backlash in the US. But social activism is ceaseless in American history.

Advertisement

Black literature has been the most important repository of the history of opposition and the spirit of resistance in America. Not long after the 2016 election, PEN held a demonstration on the steps of the New York Public Library, at which three young white women read together from Letters to a Young Artist (2006) by the playwright and actor Anna Deavere Smith: “My job in my work is not to acquire power; it’s to question power. What I say I believe is that my job is to see the world upside down, to doubt, to question, to ask. I hope I believe what I say I believe.”

The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race, edited by the novelist and memoirist Jesmyn Ward, originated in her search for community and consolation after the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012:

I needed words. The ephemera of Twitter, the way the voices of the outraged public rose and sank so quickly, flitting from topic to topic, disappointed me. I wanted to hold these words to my chest, take comfort in the fact that others were angry, others were agitating for justice, others could not get Trayvon’s baby face out of their heads…. I couldn’t fully satisfy my need for kinship in this struggle, commiserate with others trying to find a way out of that dark closet. In desperation, I sought James Baldwin….Baldwin was so brutally honest.

In addition to Ward’s own essay on her light-skinned family in Mississippi and what her discovery through DNA testing of her very mixed ancestry has done to her definitions of blackness, The Fire This Time features poetry by Jericho Brown, Clint Smith, and Natasha Trethewey, and Kima Jones’s remembrance of a grandfather’s wake that is like a tone poem. There are also thirteen essays by historians, journalists, novelists, critics, and other poets, all young, or youngish, and already accomplished.

In “Da Art of Storytellin’ (a Prequel),” Kiese Laymon, a novelist and a columnist for The Guardian, recalls his grandmother in Mississippi who worked as a “buttonhole slicer,” gutting chickens at a poultry-processing plant. When she came home from work she would say to him, “Let me wash this stank off my hands before I hug your neck.”

This stank wasn’t that stink. This stank was root and residue of black Southern poverty, and devalued black Southern labor, black Southern excellence, black Southern imagination, and black Southern woman magic. This was the stank from which black Southern life, love, and labor came.

But he didn’t understand “this stank” and the culture of black southern life until years later, through the revelatory power of hip-hop. When at college in Ohio in 1996 he heard the album ATLiens by the group Outkast, it changed his expectations of himself as “a young black Southern artist.” He said he knew he had to write in order “to be a decent human being.”

Mitchell S. Jackson, also a novelist, describes in “Composite Pops” how he made up his father from the men who came into his life: a witty pimp with whom his mother had two boys; his maternal grandfather, who became his “caretaker” after he ran away from his biological father; his maternal uncle, who trained him in track; his paternal uncle, a drug kingpin, from whom he learned how to hustle; and his biological father, a married man. Now the father of two children himself, Jackson extracts what could be called a tale of nurturing from a background of violence and dysfunction. In a humorous footnote, Jackson reviews the father substitutes of Obama, Washington, Jefferson, and Gerald Ford.

Several of the essays fuse personal past with cultural history as their authors locate where they belong in the black American story. Wendy S. Walters became interested in an African burial ground that had been discovered in 2003 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire:

Pieces of the skull, portions of the upper and lower limbs, shoulder girdle, ribs, spine, and pelvis of a male person between the ages of twenty-one and thirty years represent Burial 1. An excavator operator noticed his leg bones sticking out from the bottom of his coffin, which was made of white pine and was hexagonal in shape.

She hadn’t explored slave history until she began her quest in the library to learn more about the site and met resistance from custodians of colonial heritage who mistrusted her intentions.

The poet Honorée Fanonne Jeffers reconsiders the role of Phillis Wheatley’s husband in her tragic life. Wheatley was an African child acquired by Boston merchants who proved such a scholar that in 1773 she published Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. Wheatley was freed, but not much is known about her life after the death of her former mistress and protector. Wheatley died in 1784, maybe thirty-three or thirty-four years old. The accepted story had been that she died after having lost three children to sickness in their infancy. Her husband, John Peters, an alleged wastrel, sold the manuscript of her second book of poems, which was then lost.

Advertisement

However, Jeffers questions the one source of information about Peters, a memoir published in 1834 by a white woman claiming collateral descent from Wheatley’s mistress. Spurred on by other scholars’ work, Jeffers tracked Peters through the census and legal documents. She speculates that he was a free man of education struggling in the volatile post–Revolutionary War economy. There is no certain evidence of how Wheatley died, or how many children she had, or if a child died with her. Jeffers suspects that John Peters, as a black man with aspirations, has been slandered in death.

Garnette Cadogan’s “Black and Blue” relates that in his hometown, Kingston, Jamaica, he was a walker, but in New Orleans, where he went to college in 1996, he had to learn that he did not have the same freedom to walk in a white-controlled city. A cop put him in handcuffs just for waving at him. After Hurricane Katrina he made his way to New York, in order to “continue to reap the solace of walking at night. And I was eager to follow in the steps of the essayists, poets, and novelists who’d wandered that great city before me—Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, Alfred Kazin, Elizabeth Hardwick.” But one night in the East Village he was running to dinner when a white guy punched him hard. He had assumed that Cadogan was a criminal. Strangely passive, or determined to survive, Cadogan went back to rules he’d set for himself in New Orleans: no running, no sudden movements, no hoodies, no shiny objects in his hand, no waiting on corners. But then he forgot and the next time he was hurrying to an appointment, he ended up handcuffed and humiliated by several policemen.

Cadogan notes that “walking while black restricts the experience of walking.” He cannot be alone, a flaneur occupied with his own thoughts. Instead of walking in Whitman’s or Melville’s steps,

more often I felt that I was tiptoeing in Baldwin’s—the Baldwin who wrote, way back in 1960, “Rare, indeed, is the Harlem citizen, from the most circumspect church member to the most shiftless adolescent, who does not have a long tale to tell of police incompetence, injustice, or brutality. I myself have witnessed and endured it more than once.”

“‘KNOW YOUR RIGHTS!’ the mural trumpeted in capital letters,” writes Emily Raboteau, a novelist and memoirist, who is also on foot in her essay, walking in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens, and photographing street murals, which are reproduced in the anthology. A text in one mural begins, “Write down the officer’s badge number, name….” Another mural contains the words, “If you are Harassed by police…” Raboteau is looking at the city streets and thinking of when she will have to have the conversation with her children about how to protect themselves from the police.

Most of the essays in The Fire This Time describe suffering, defiance, and aspiration that culminate in identification with the Black Lives Matter movement. The poet Claudia Rankine remembers a friend whose first thought when she gave birth to her son was not what his name would be, but how she was going to get him out of the country. Rankine was born in 1963, days after the murder of four black girls in a church in Birmingham, Alabama. Just over a half-century later, a white supremacist massacred blacks at prayer in a Charleston, South Carolina, church. “Americans assimilate corpses in their daily comings and goings. Dead blacks are a part of normal life here,” she writes.

In her essay Rankine discusses the reactions of black mothers to the murder of their sons. By requesting an open coffin and allowing photographs of Emmett Till’s disfigured body to be published after he was lynched in 1955, his mother was defying the tradition of whites posing in front of hanged black bodies, Rankine observes with passion. Michael Brown’s mother was kept from his body after he was shot in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. Tamir Rice’s mother moved into a homeless shelter rather than live near the scene of her twelve-year-old son’s killing by police in Cleveland the same year. The Black Lives Matter movement is, for Rankine, “an attempt to keep mourning an open dynamic in our culture because black lives exist in a state of precariousness.”

In “Blacker Than Thou,” the poet and Schomburg Center director Kevin Young writes about the bizarre case of Rachel Dolezal, the white woman who passed for black and became head of her NAACP chapter in Spokane, Washington:

When you are black, you don’t have to look like it, but you do have to look at it. Or look around. Blackness is the face in the mirror, a not-bad-looking one, that for no reason at all some people uglify or hate on or wish ill for, to, about. Sometimes any lusting after it gets to be a drag too.

But the murders in the Charleston church in 2015 made such a figure ridiculous, he concludes:

This morning I woke from a “deep Negro sleep,” as Senghor put it. I then took a black shower and shaved a black shave; I walked a black walk and sat a black sit; I wrote some black lines; I coughed black and sneezed black and ate black too. This last at least is literal: grapes, blackberries, the ripest plums.

Edwidge Danticat, in her discomforting essay “Message to My Daughters,” ponders whether African-Americans are like refugees in their own country. Born in Haiti, brought up in Brooklyn, where she knew victims of police violence, Danticat contends that black people have always been treated as a population in transit, housed and educated in conditions not much better than those of refugees. After Michael Brown’s murder, Danticat’s friend Abner Louima—we forget that he survived the police assault in 1997, when he was sodomized in a Brooklyn precinct station—told her that the young man’s death proved that “our lives mean nothing.” But Danticat doesn’t want her daughters to grow up terrified, as she did. She wants to be optimistic. Her version of Baldwin’s “My Dungeon Shook,” she promises, will ask her daughters to believe that they have a right to be here.

The theme of trespass is taken up by Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, who was persuaded, as she remembers in “The Weight,” to make a pilgrimage to Baldwin’s home in St. Paul de Vence, France, two decades after his death. Though she couldn’t afford the trip, she had “an unspoken hoodoo-ish belief that he had been the high priest in charge of my prayer of being a black person who wanted to exist on books and words alone.” She’d had her spell of coolness toward Baldwin: he set the stage for every American essayist after him, but one didn’t have to emulate or worship him as “the black authorial exception.” She minded that every essay on race cited him and that he’d escaped to France while her grandfather, who was Baldwin’s age, could only hope for a little dignity in his working life.

Then Ghansah, born in 1981, went to work as the first black intern at a prestigious magazine in New York that had never had a black editor in its 150-year history. Her real world was a privileged one, but she found a need for Baldwin’s words, even there. In St. Paul de Vence, she toured a property without doors or windowpanes, beer cans strewn about, postings from the company that was to tear the house down. It was not his memorial: “He wrote it all down. And this is how his memory is carried…. What Baldwin knew is that he left no heirs, he left spares, and that is why we carry him with us.”

In part because of Baldwin’s example, many of the old questions are mute. Black Lives Matter—founded in 2012 by three women brought together on social media after one of them, Alicia Garza, responded to the murder of Trayvon Martin by writing an open letter to black people—tries to answer the question that confronted many in the Black Arts movement of the 1960s: How can an artist also be an activist? A black writer is by no means obliged to write about black matters. But Wright’s definition of the black artist who challenged power and defended blacks offers more than Ellison’s insistence that being the best novelist he could be was his contribution to the black struggle. Baldwin didn’t want to be Wright’s heir, any more than Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah wanted to be Baldwin’s.

But the young black writers in this anthology reflect in their work how long ago The Fire Next Time was. That world of blacks not looking at one another, ashamed to look at themselves, describes an atmosphere before the black consciousness movement that would spread soon after the publication of Baldwin’s essay. Some fifty years later, invisibility is over; the shame is gone. Nevertheless, Alicia Garza felt that what black people needed from her was a letter asking them to love themselves.