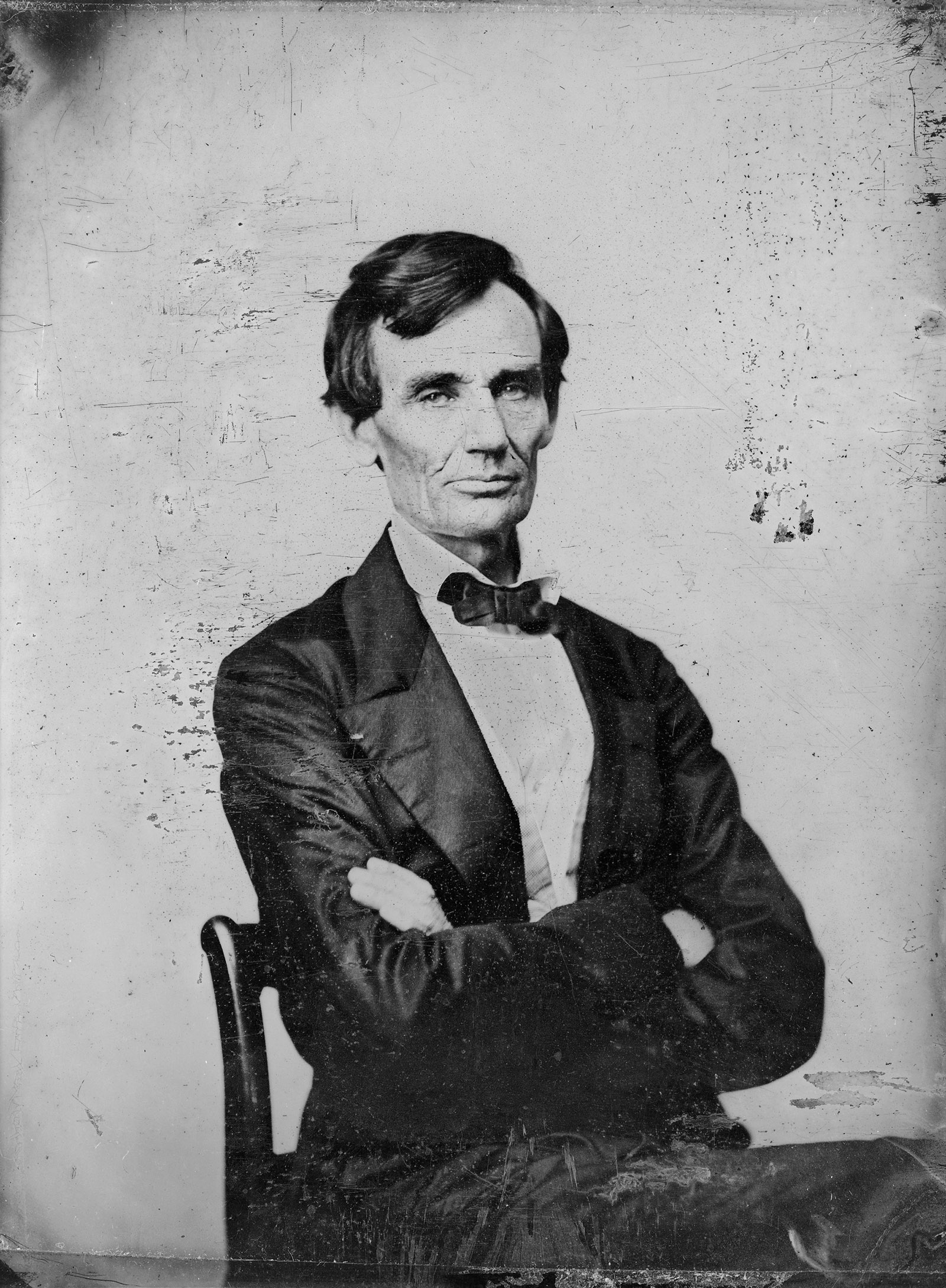

By the time Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as president in 1861, Africans and their descendants had been enslaved in North America for about 250 years. Slavery had survived wars and revolutions, economic upheavals, and a variety of governments. Fifteen presidents had come and gone, as had more than thirty Congresses, and not one of them had made a serious effort to undermine slavery. Yet within a mere eighteen months of taking the oath of office, Lincoln announced the emancipation of three million slaves in the southern states, sounding what Eric Foner called “the death knell of slavery.” Why did Lincoln move so fast? Why did he so quickly commit the United States to the complete destruction of a slave system that, until his election, had not only survived but flourished for a quarter of a millennium?

It is one of the virtues of Sidney Blumenthal’s account in The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln that it does not approach this question by reference to Lincoln’s biography alone. The details of Lincoln’s life are woven throughout the two volumes so far published. (There are two more to come.) But the one thousand pages we already have take us only up to 1856, when Lincoln joined the newly formed Republican Party, and the documentation of his life until that point is too scant to fill so much space. What Blumenthal has given us instead is a sprawling account of the larger political history of the United States, within which he places the details of Lincoln’s biography. These two volumes are a study less of Lincoln’s political life than of his political world. It was a world dominated for decades by an increasingly intractable debate over slavery.

Approaching his subject in this way leads Blumenthal down a number of obscure byways that, at first glance, seem to be of no great relevance to Lincoln’s political life. There are long stretches during which Lincoln disappears completely. An entire chapter is devoted to a lively account of the politically charged history of Mormons in Illinois in the 1840s. Another covers the 1853 whirlwind tour of the United States by Louis Kossuth, the Hungarian freedom fighter. The text contains engaging mini-biographies of dozens of characters, some of whom were dead by the time Lincoln was first elected to office.

Every presidential election campaign is reconstructed; every candidate for every party’s nomination is introduced. It’s easy to get lost in the details of local politics in Springfield, Illinois; the philosophical writings of Comte, Volney, and Thomas Paine; lawsuits in Lexington, Kentucky; or the shady financial deals of Stephen Douglas. The first volume, A Self-Made Man, feels particularly baggy, and I confess that I was halfway through the second, Wrestling with His Angel, before I could discern the broad outlines of Blumenthal’s impressive intellectual project. There is method to his randomness. In a way, Blumenthal is building an explanation for how Lincoln got to the Emancipation Proclamation.

1.

In 1864 James Gordon Bennett, editor of the New York Herald, described Lincoln as “the keenest of politicians, and more than a match for his wily antagonists in the arts of diplomacy.” Charles Henry Dana, Lincoln’s assistant secretary of war, agreed. “Lincoln was a supreme politician,” Dana recalled. “He never stepped too soon, and he never stepped too late.” Whatever else we choose to make of Lincoln—Great Emancipator or white supremacist, redeemer of the Union or executive tyrant—it’s hard to deny that he was, from beginning to end, a partisan politician. “The secret of Lincoln’s success is simple,” the historian David Donald explained in a classic essay, “A. Lincoln, Politician.” “He was an astute and dexterous operator of the political machine.” Blumenthal is the latest in a long line of chroniclers to echo Donald’s observation. Lincoln, Blumenthal writes, was “one of the most astute professional politicians the country has produced.”

Admiration for Lincoln’s political genius is most often directed to his performance as president and commander in chief—how he held his fractious party together, managed his disorderly cabinet, appealed for unity across party lines, and persuaded northerners to accept emancipation as a necessary step to save the Union. No doubt Blumenthal will address those issues in future volumes, but it is already clear that he is taking a distinctive approach to an otherwise conventional story. That story, as he tells it, is almost always about slavery and the political conflicts it aroused. Wherever he looks, whether in Illinois, Washington, D.C., Indiana, Kentucky, or Missouri, whether he’s digging into the history of railroads or of foreign relations, Blumenthal finds a struggle over slavery that was steadily becoming irreconcilable. The opening chapters of A Self-Made Man focus on Lincoln’s early life, but they tilt in the same direction.

Advertisement

Lincoln once said that he was “naturally antislavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not so think and feel.” Presumably this means that he had absorbed his antislavery views when he was very young, a point now widely accepted among historians and affirmed by Blumenthal. Lincoln’s parents attended an antislavery church. He later said that his father moved their family from Kentucky to Indiana mostly for economic reasons, but in part to get away from slavery. Lincoln taught himself the art of rhetoric by perusing antislavery speeches reprinted in the schoolbooks he managed to get his hands on as a boy. While still a young man Lincoln rode flatboats down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, and decades later he recalled how disturbed he had been by the sight of slaves chained together or sold at auctions in the Crescent City.

Lincoln left home at the age of twenty-two and within a year embarked on a political career. On March 9, 1832, he announced his candidacy for a seat in the Illinois General Assembly as a representative of Sangamon County. He introduced himself as an enthusiastic supporter of improvements such as railroads, turnpikes, and public schools—government projects designed to spur economic development and promote the general welfare of the people. At the national level, this legislative agenda, led by Henry Clay, was known as the American System and became the distinctive platform of the emerging Whig Party. But in 1832 Lincoln was thinking locally, and in announcing his candidacy he focused on clearing and straightening the Sangamon River so the people of his district could more easily export their “surplus products” and import “necessary articles from abroad.”

Lincoln lost that first election, but he spent the next couple of years making himself more widely known throughout the county. In 1834 he ran again, this time successfully. He was reelected three more times, serving a total of eight years, during which his most conspicuous accomplishment was his leadership of the campaign to move the state capital from Vandalia to Springfield. But if his legislative record was meager, Lincoln was all the while sharpening his partisan skills.

He wrote anonymous editorials for local papers hurling scandalous accusations at his opponents. He belittled their manhood and made fun of their religious convictions. Though never personally corrupt, Lincoln scrambled for patronage for himself and his favorites in the Whig Party. He was in many ways a partisan hack, but he was also an increasingly effective popular leader, party organizer, and coalition builder.

It was in those same years that Lincoln first put himself on the public record in opposition to slavery. On March 3, 1837, he signed a public protest declaring that “the institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy.” Blumenthal rightly sees this as a local manifestation of a national controversy. Proslavery politicians were claiming that Congress lacked the power to abolish slavery in Washington, D.C., because slave ownership was protected as a fundamental right of property. By contrast Lincoln invoked the broad antislavery principle that Congress could, “under the constitution,” abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. By implication, Congress could do several other things as well.

After four terms Lincoln resigned from the state legislature and in 1846 was elected to the US House of Representatives. When he arrived in Washington the following year, Congress was in an uproar caused by the Mexican–American War. In the North the war was widely viewed as a proslavery swindle, and Lincoln readily joined the majority of northern congressmen who repeatedly voted to ban slavery in any territory snatched from Mexico. While in Washington, Lincoln also drafted a moderate statute for the abolition of slavery in Washington and supported a number of resolutions along those same lines.

Lincoln earned nothing but ridicule for his opposition to the Mexican war, and his political career stalled. He served only one term in Congress, after which he returned to Illinois in 1849 where he had little choice but to concentrate on his legal practice. A Self-Made Man concludes at this point. “His antislavery gestures in the legislature and the Congress came to naught and were largely ignored,” Blumenthal writes. “He had learned the arts and letters of politics in the new republic. But even proficiency was insufficient. He was at a dead end.”

As was true of the first volume, Wrestling with His Angel opens with biographical details from Lincoln’s life, in this case a lawsuit over his father-in-law’s estate that took him to Kentucky. There Lincoln witnessed close up the final destruction of antislavery forces in that state. But once again biography gives way to political history as Blumenthal moves on to an extended account of the so-called Compromise of 1850. (Lincoln, back in Springfield practicing law, is not part of this story.)

Advertisement

The details of Blumenthal’s account are familiar, but he arranges them in order to foreshadow the next dramatic shift in Lincoln’s political career, which began with the death of Henry Clay, his “beau ideal” of a statesman. It was Clay who fashioned the various elements of the Compromise of 1850. But unable to secure its passage through Congress, Clay left Washington exhausted, frustrated, and frail. He would be dead within two years. Blumenthal sees Clay’s departure as the beginning of the end of the Whig Party he had founded and to which Lincoln had long been devoted. The political ground was shifting beneath Lincoln’s feet.

John C. Calhoun likewise made his final appearance in national politics in 1850, rising from his deathbed to denounce the compromise. With Calhoun gone, Blumenthal concentrates on his protégé and successor, Jefferson Davis, who soon emerged as the leader of the increasingly intransigent proslavery forces in national politics. Like Calhoun, Davis opposed the compromise and would exercise his formidable influence to destroy it a few years later. But Davis is not yet the lead character in the story Blumenthal is telling.

The dark knight in this tale, the archrival with whom “Lincoln was locked in mortal combat,” is still Stephen Douglas. In A Self-Made Man Blumenthal traces the rivalry between Lincoln and Douglas all the way back to the 1830s—not only in the head-to-head confrontations between them, but also in the war of words between Whig and Democratic newspapers, in the partisan struggles within the Illinois legislature, in the competition for Mary Todd’s affections, in the shifting appeals for support from Joseph Smith’s Mormons, and most often in the “shadow” matches between candidates who were proxies for either Lincoln or Douglas. Through it all, and to his immense frustration, Lincoln’s political star faded as Douglas’s rose.

Wrestling with His Angel is as much Douglas’s story as Lincoln’s, beginning with Douglas’s triumphant rescue of Clay’s compromise measures. Clay had put together a package of items—some appealing to antislavery northerners and others to proslavery southerners—and bundled them together in what was derisively dubbed the “omnibus” bill. That strategy backfired. It alienated each side so that instead of maximizing support, the omnibus approach ensured the bill’s downfall. But as Clay retreated in defeat, Douglas assumed control of the situation. He broke Clay’s bill into individual pieces, each sufficiently appealing to win different majorities. The compromise was saved, and Douglas proclaimed himself the hero of the hour. Whigs and Democrats alike declared that the slavery issue was settled, permanently, never again to disrupt national politics. Reveling in his triumph, Douglas fixed his eyes on the presidency.

But Douglas was not only ambitious, he was also greedy—not to mention scurrilous, deceitful, and ruthless. Blumenthal’s portrait of the “Little Giant”—as Douglas was known because of his short stature—is merciless. If Jefferson Davis comes off as a humorless ideologue, Douglas is an unprincipled demagogue. He capitalized on his legislative triumph in 1850 to secure congressional passage of a railroad bill that, not coincidentally, made him rich from real estate investments in Chicago. His appetite whetted, Douglas tried it again in 1854, this time with plans for a transcontinental railroad that would make him richer still. In order for his well-situated investments to pay off, Douglas had to incorporate the Nebraska Territory, but to do that he needed southern support. The price Davis and his fellow southerners extorted for endorsement of Douglas’s territorial bill was the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, which had banned slavery in the Nebraska Territory since 1820. Douglas willingly complied, secured passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, and made a fortune.

It is hard to overstate the seismic upheaval Douglas had set in motion. The Whig Party was already reeling from the northern backlash against the Fugitive Slave Act, which had been passed as part of the Compromise of 1850. But that was nothing compared to the political rebellion unleashed by the Nebraska bill’s repeal of the Missouri Compromise. Anti-Nebraska parties sprang up across the North, where Democrats suffered disastrous defeats in the 1854 elections. With both major parties spinning off dissenting factions, northern politicians scrambled to fuse the discordant elements into a new coalition. For a while it was unclear whether a new party would coalesce around hostility to the expansion of slavery or hostility to Catholic immigrants. Disdainful of the anti-immigrant fever and with no Whig Party left to cling to, Lincoln threw in his lot with the new Republican Party.

The Nebraska controversy had revived Lincoln’s political career. He shadowed Douglas from town to town perfecting the first of his great antislavery speeches—known ever after as the Peoria speech. This was a different Lincoln, Blumenthal believes, a mature statesman rather than a party hack. But the political circumstances had changed at least as much as the man. Lincoln’s lifelong hostility to slavery had been held in check for as long as he remained loyal to the Whig Party, with its powerful southern wing. The decimation of his beloved Whigs and the consequent rise of the antislavery Republican Party actually liberated Lincoln. For the first time in his political life his partisan allegiance aligned with his antislavery convictions.

2.

Although The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln is anything but a conventional biography, it often reads like a series of biographical sketches. Blumenthal cites a number of previous biographies that provide a substantial proportion of his source material. And although he draws on many of the major speeches and writings of the characters he discusses, these two volumes are works of synthesis more than of original scholarship. Where Blumenthal does rely on primary sources, they are often memoirs or recollections that are not always reliable. He knows this, and he occasionally goes out of his way to debunk a familiar story by disputing the source. But Blumenthal is not always discerning in his use of recollected material, and he has a disconcerting habit of telling a story and quoting a source only to reveal that the anecdote is probably apocryphal and the source untrustworthy.

As expansive as his understanding of Lincoln’s political world is, Blumenthal’s account is in other ways narrowly conceived. This is a view of history in which politics is largely explained by reference to more politics, an approach that tends to discount pressure from outside the political system itself. How, for example, might we account for the enormous impact the issue of fugitive slaves had on national politics before and during the Civil War? Why did tens of thousands of women enlist in the abolitionist movement, and why was gender such a prominent theme in antislavery politics? Why were abolitionists forced for so long to operate outside the two-party system, and what was the influence the movement ultimately had on the political mainstream? What was it about the northern economy that made it so much more dynamic than the South’s, and how did that shift the balance of political power away from the slave states? Sometimes explaining politics demands that the historian step outside of politics.

And yet this may be unfair, a case of a critic complaining that the author should have written a different book. Blumenthal is the ideal author for the kind of history he writes. He has a journalist’s eye for the telling detail, and he passes judgment with the skill of a practiced polemicist. As a political strategist with close ties to Bill and Hillary Clinton, Blumenthal has an insider’s feel for the nitty-gritty of politics. He smells rats from miles away. He revels in the details of backroom deals and exposes shady maneuvers and sharp practices with clarity and panache. He skewers zealots and liars with gusto and yet remains unfazed by the sordidness of it all. Blumenthal writes as an antislavery partisan, but like any good politician, he does not make the mistake of underestimating his opponents.

The result is political history that resists both naiveté and cynicism. This is because Blumenthal appreciates the good that can sometimes be done by politicians like Lincoln. He closes Wrestling with His Angel with an observation by John Bunn, a fellow Whig who worked closely with Lincoln in Springfield:

Lincoln’s entire career proves that it is quite possible for a man to be adroit and skillful and effective in politics, without in any degree sacrificing moral principles.

I’m not sure this is entirely correct. Lincoln certainly had his principles, but not all of them were lovely, and he did occasionally bend the ones that were. But Bunn was mostly right, and Blumenthal shares his respect for Lincoln’s shrewd combination of pragmatism and principle. It is the animating premise of both books.

3.

In 1858, two years after he committed himself to the Republican Party, Lincoln once more confronted his archrival in what became the most celebrated senatorial contest in US history. The seven debates between Lincoln and Douglas would become classics of American political rhetoric. As the campaign proceeded, Lincoln steadily found his voice and concluded with some of the most eloquent passages ever uttered in defense of human dignity and universal freedom. Douglas went the other way, descending to a shocking level of vulgarity, mendacity, and unabashed racial demagoguery. He warned voters that if Lincoln had his way the slaves would be freed and savage blacks would swarm across the southern borders of Illinois, where they would threaten the purity of the wives and daughters of free white men.

For Lincoln, the outcome of the election could hardly have been more frustrating. The Republicans won the popular vote, but at the time senators were chosen by state legislatures, and the Illinois legislature, still dominated by Douglas’s Democrats, returned the shameless demagogue to the Senate. On his way back to Washington, Douglas gave a series of speeches in which he likened blacks to a species of animal somewhere between a human being and a crocodile. But there was only so much of this that people were willing to take. For years Douglas had finessed the slavery issue with his call for “popular sovereignty,” an idea Blumenthal sees as little more than a publicity stunt. In 1860 the stunt was no longer working. In the final contest between the two great rivals the voters chose Lincoln over Douglas as the next president of the United States.

If Blumenthal has demonstrated anything, it is that by the time Lincoln took his oath of office, the debate over slavery had been at or near the center of American politics for at least forty years. For most of that time slaveholders controlled the presidency, Congress, and the Supreme Court. But with each passing decade the balance of economic power shifted to the North, and Wrestling with His Angel traces the corresponding shift in political power, culminating in the establishment of the Republican Party.

In 1861 Lincoln became the first president elected on an antislavery platform. He made no secret of the fact that he had always hated slavery. He had long since publicly endorsed a host of federal policies designed to put slavery on a peaceful course of ultimate extinction. But he had also concluded that slavery was more likely to end in violence, and he warned that if the slave states responded to his election by seceding from the Union they would forfeit any claim to federal protection of slavery.

No wonder he moved so quickly. Within a mere eighteen months of taking office Lincoln committed the federal government to the overthrow of the largest and wealthiest slave system in the hemisphere, a system that had prospered for two and a half centuries. Revolutions of this magnitude are not the incidental byproducts of war. They are a long time in the making, although when they come they often come quickly. For anyone wondering why Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation so soon after taking office, Sidney Blumenthal’s expansive political life of the sixteenth president is a good place to start looking for an answer.