As our newspapers and TV screens overflow with choleric attacks by President Trump on the media, immigrants, and anyone who criticizes him, it makes us wonder: What would it be like if nothing restrained him from his obvious wish to silence, deport, or jail such enemies? For a chilling answer, we need only roll back the clock one hundred years, to the moment when the United States entered not just a world war, but a three-year period of unparalleled censorship, mass imprisonment, and anti-immigrant terror.

When Woodrow Wilson went before Congress on April 2, 1917, and asked it to declare war against Germany, the country, as it is today, was riven by discord. Even though millions of people from the perennially bellicose Theodore Roosevelt on down were eager for war, President Wilson was not sure he could count on the loyalty of some nine million German-Americans, or of the 4.5 million Irish-Americans who might be reluctant to fight as allies of Britain. Also, hundreds of officials elected to state and local office belonged to the Socialist Party, which strongly opposed American participation in this or any other war. And tens of thousands of Americans were “Wobblies,” members of the militant Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and the only battle they wanted to fight was that of labor against capital.

The moment the United States entered the war in Europe, a second, less noticed war began at home. Staffed by federal agents, local police, and civilian vigilantes, it had three main targets: anyone who might be a German sympathizer, left-wing newspapers and magazines, and labor activists. The war against the last two groups would continue for a year and a half after World War I ended.

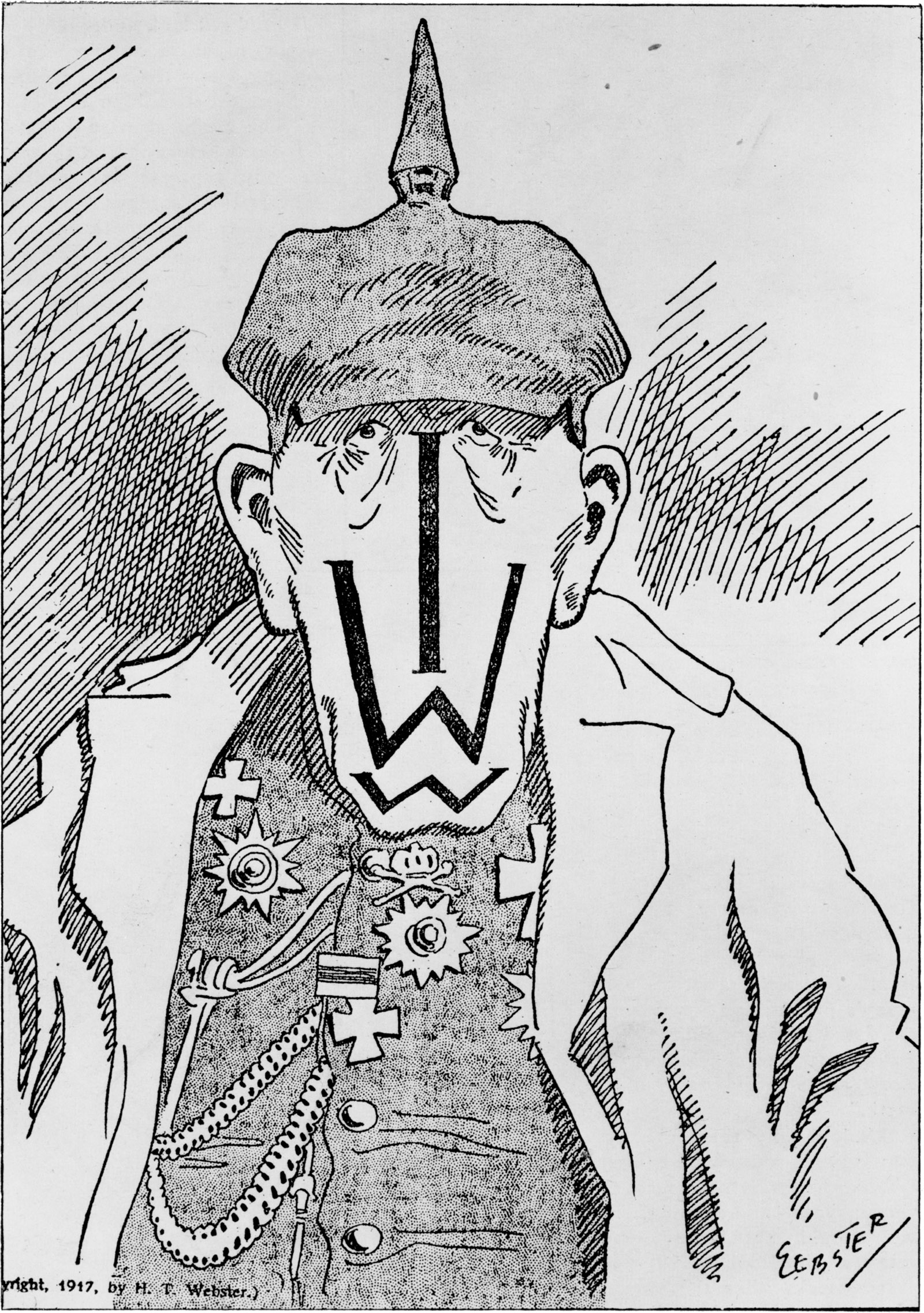

In a strikingly Trumpian fashion, President Wilson himself helped sow suspicion of anything German. He had run for reelection in 1916 on the slogan “he kept us out of war,” but he also knew American public opinion was strongly anti-German. Even before the declaration of war, he had darkly warned that “there are citizens of the United States, I blush to admit, born under other flags…who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life…. Such creatures of passion, disloyalty, and anarchy must be crushed out.”

Once the US entered the war immediately after Wilson’s second term began, the crushing swiftly reached a frenzy. The government started arresting and interning native-born Germans who were not naturalized US citizens—but in a highly selective way, seizing, for example, all those who were IWW members. Millions of Americans rushed to spurn anything German. Families named Schmidt quickly became Smith. German-language textbooks were tossed on bonfires. The German-born conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Karl Muck, was locked up, even though he was a citizen of Switzerland; notes he had made on a score of the St. Matthew Passion were suspected of being coded messages to Germany. Berlin, Iowa, changed its name to Lincoln, and East Germantown, Indiana, became Pershing, after the general leading American soldiers in their broad-brimmed hats to France. Hamburger was now “Salisbury steak” and German measles “Liberty measles.” The New York Herald published the names and addresses of every German or Austro-Hungarian national living in the city.

Citizens everywhere took the law into their hands. In Collinsville, Illinois, a crowd seized a coal miner, Robert Prager, who had the bad luck to be German-born. They kicked and punched him, stripped off his clothes, wrapped him in an American flag, forced him to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner,” marched him to a tree on the outskirts of town, and lynched him. It didn’t matter that he had tried to enlist in the US Navy but been turned down because he had a glass eye. After a jury deliberated for only forty-five minutes, eleven members of the mob were acquitted of all charges while a military band played outside the courthouse.

The next battle was an assault on the media unmatched in American history before or—so far—since. Its commander was Wilson’s postmaster general, Albert Sidney Burleson, a pompous former prosecutor and congressman. On June 16, 1917, he sent sweeping instructions to local postmasters ordering them to “keep a close watch on unsealed matters, newspapers, etc.” for anything “calculated to…cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny…or otherwise embarrass or hamper the Government in conducting the war.” What did “embarrass” mean? A subsequent Burleson edict gave a broad range of examples, from saying “that the Government is controlled by Wall Street or munition manufacturers, or any other special interests” to “attacking improperly our allies.”

One after another, Burleson went after newspapers and magazines, many of them affiliated with the Socialist Party, including the popular Appeal to Reason, which had a circulation of more than half a million. Virtually all Wobbly literature was banned from the mail. Burleson’s most famous target was Max Eastman’s vigorously antiwar The Masses, the literary journal that had published everyone from John Reed to Sherwood Anderson to Edna St. Vincent Millay to the young Walter Lippmann. While The Masses never actually reached the masses—its circulation averaged a mere 12,000—it was one of the liveliest magazines this country has ever produced. Burleson shut it down; one of the items that drew his ire was a cartoon of the Liberty Bell crumbling. “They give you ninety days for quoting the Declaration of Independence,” declared Eastman, “six months for quoting the Bible.”

Advertisement

With so many recent immigrants, the United States had dozens of foreign-language papers. All were now required to submit to the local postmaster English translations of all articles dealing with the government, the war, or American allies before they could be published—a ruinous expense that caused many periodicals to stop printing. Another Burleson technique was to ban a particular issue of a newspaper or magazine, and then cancel its second-class mailing permit, claiming that it was no longer publishing regularly. Before the war was over, seventy-five different publications would be either censored or completely banned.

Finally, the war gave business and government the perfect excuse to attack the labor movement. The preceding eight years had been ones of great labor strife, with hundreds of thousands of workers on strike every year; now, virtually every IWW office was raided. In Seattle, authorities turned Wobbly prisoners over to the local army commander, then claimed that because they were in military custody, habeas corpus did not apply. In Chicago, when 101 Wobblies were put through a four-month trial, a jury found all of them guilty after a discussion so brief it averaged less than thirty seconds per defendant. By the time of the Armistice, there would be nearly 6,300 warranted arrests of leftists of all varieties, but thousands more people, the total unknown, were seized without warrants.

Much repression never showed up in statistics because it was done by vigilantes. In June 1917, for example, copper miners in Bisbee, Arizona, organized by the IWW, went on strike. A few weeks later, the local sheriff formed a posse of more than two thousand mining company officials, hired gunmen, and armed local businessmen. Wearing white armbands to identify themselves and led by a car mounted with a machine gun, they broke down doors and marched nearly twelve hundred strikers and their supporters out of town. The men were held for several hours under the hot sun in a baseball park, then forced at bayonet point into a train of two dozen cattle and freight cars and hauled, with armed guards atop each car and more armed men escorting the train in automobiles, 180 miles through the desert and across the state line to New Mexico. After two days without food, they were placed in a US Army stockade. A few months later, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a mob wearing hoods seized seventeen Wobblies and whipped, tarred, and feathered them.

Even people from the highest reaches of society bayed for blood like a lynch mob. Elihu Root, a corporate lawyer and former secretary of war, secretary of state, and senator, was the prototype of the so-called wise men of the twentieth-century foreign policy establishment who moved easily back and forth between Wall Street and Washington. “There are men walking about the streets of this city tonight who ought to be taken out at sunrise tomorrow and shot,” he told an audience at New York’s Union League Club in August 1917. “There are some newspapers published in this city every day the editors of which deserve conviction and execution for treason.”

Woodrow Wilson is remembered for promoting the League of Nations to resolve conflicts abroad in an orderly fashion, but at home his Justice Department encouraged the formation of vigilante groups with names like the Knights of Liberty and the Sedition Slammers. The largest was the American Protective League (APL), with 250,000 members by the end of the war, some of them from existing business organizations, like California’s Midway Oilfields Protective Committee, whose membership joined as a group. Its ranks filled with employers who hated unions, nativists who hated immigrants, and men too old for the military who still wanted to do battle. APL members carried badges labeled “Auxiliary of the US Department of Justice,” and the Post Office gave them the franking privilege of sending mail for free.

The government offered a $50 bounty for every proven draft evader, which brought untold thousands to the hunt, from underpaid rural sheriffs to the big-city unemployed. Throughout the country, the APL carried out “slacker raids,” sometimes together with uniformed soldiers and sailors. One September 1918 raid in New York City and its vicinity netted more than 60,000 men. Only 199 actual draft dodgers were found among them, but many of the remainder were held for days while their records were checked. Wilson approvingly told the secretary of the navy that the raids would “put the fear of God” in draft dodgers.

Advertisement

Although brave and outspoken, Americans who opposed the war were only a minority of the population. The Wilson administration’s harsh treatment of them had considerable popular support. In early 1917 the unrestricted German submarine attacks on American ships taking cargo to the Allies and the notorious Zimmerman telegram, promising Mexico a slice of the American Southwest if it joined the war on Germany’s side, fanned outrage against Germany. The targeting of so many leftists and labor leaders who were immigrants, Jewish, or both drew on a powerful undercurrent of nativism and anti-Semitism. And millions of young men, still ignorant of trench warfare’s horrors, were eager to fight and ready to be hostile to anyone who seemed to stand in their way.

By the time the war ended the government had a new excuse for continuing the crackdown: the Russian Revolution, which was blamed for any unrest, such as a wave of large postwar strikes in 1919. These were ruthlessly suppressed. Gary, Indiana, was put under martial law, and army tanks were called out in Cleveland. When bombs went off in New York, Washington, and several other cities, they were almost certainly all set by a small group of Italian anarchists (indeed, one managed to blow himself up in the process). But “alternative facts” reigned: the director of the Bureau of Investigation, predecessor of the FBI, claimed the bombers were “connected with Russian bolshevism.”

The same year an outburst of protest by black Americans provided a pretext for vicious racist violence. Nearly four hundred thousand blacks had served in the military, then come home to a country where they were denied good jobs, schooling, and housing. As they competed with millions of returning white soldiers for scarce work, race riots broke out, and that summer more than 120 people were killed. Lynchings—a steady, terrifying feature of black life for many years—reached the highest point in more than a decade; seventy-eight African-Americans were lynched in 1919, more than one per week. But all racial tension was also blamed on the Russians. Wilson himself predicted that “the American negro returning from abroad would be our greatest medium in conveying Bolshevism to America.”

This three-year period of repression reached a peak in late 1919 and early 1920 with the “Palmer Raids,” under the direction of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, helped at every step by a rising young Justice Department official named John Edgar Hoover. On a single day of the raids, for example—January 2, 1920—some five thousand people were arrested; one scholar calls it “the largest single-day police roundup in American history.” The raiders were notoriously rough, beating people and throwing them down staircases. After one raid, a New York World reporter found smashed doors, overturned furniture, wrecked typewriters, and bloodstains on the floor. Eight hundred people were seized in Boston, and some of them marched through the city’s streets in chains on their way to a temporary prison on an island in the harbor. Another eight hundred were held for six days in a windowless corridor in a federal building in Detroit, with no bedding and the use of just one toilet and sink.

Palmer was startlingly open about the fact that his raids were driven by ideology. After attacking “the fanatical doctrinaires of communism in Russia,” he vowed “to keep up an unflinching, persistent, aggressive warfare against any movement, no matter how cloaked or dissembled, having for its purpose either the promulgation of these ideas or the excitation of sympathy for those who spread them.” Campaigning for the Democratic nomination for president, he hysterically predicted a widespread Bolshevik uprising on May Day, 1920, scaring authorities in Chicago into putting 360 radicals into preventive detention for the day. When the day passed and absolutely nothing happened, it became clear that the United States never had been on the verge of revolution; membership in the country’s two feuding communist parties was, after all, minuscule.

Citizens—in particular a committee of a dozen prominent lawyers, law professors, and law school deans—were emboldened to speak out against the repression, and the worst of it came to an end. But it had accomplished its purpose. The IWW was crushed, the Socialist Party reduced to a shadow of its former self, and unions forced into sharp retreat; even the determinedly moderate work-within-the-system American Federation of Labor would lose more than a million members between 1920 and 1923.

Because this sorry period of our history is too often forgotten, it’s good to see it recalled this year by several writers and filmmakers marking the centenary of America’s entry into World War I. Library of Congress staff member Margaret E. Wagner’s America and the Great War breaks no new ground but makes clear that the story of this country and that war is not only about the Lusitania and doughboys in France. She covers the war at home as well, both in the text and in photos and artwork drawn from the library’s vast collections. The illustrations, for instance, include a vigilante leaflet, dissidents like John Reed and Eugene V. Debs (imprisoned for more than two years for speaking against the war), a lynch mob, and a haunting charcoal drawing by the artist Maurice Becker, a cartoonist for The Masses, showing how he and his fellow conscientious objectors were treated in military prisons: shackled to cell bars so they would be forced to stand on tiptoe nine hours a day.

Such people and events are also evoked in The Great War, some six hours of exceptionally well-crafted film from PBS’s American Experience, which portrays a very different America from the can-do-no-wrong country of traditional war documentaries. Most of the footage is about the fighting in Europe and all that led to it, but the filmmakers do not stint in looking at the ruthless stifling of dissent at home. We learn about the division of opinion in the country, the harsh treatment of returning black veterans by the government and lynch mobs alike, and vigilantes like the American Protective League, several of whose wild-eyed reports on supposed spies and subversives are shown onscreen. The war “had great costs,” says Nancy K. Bristow, one of many historians interviewed, near the close of the film. “Not only in loss of life. That war was won, but it was won by way of behaviors, policies, and laws that contradicted the very values for which the country was fighting.”

Several other historians talk about the figure who presided over so much of what happened in those years, Woodrow Wilson. Their collective portrait is of a complex man who in the end was blinded by his own sense of righteousness. Any person or group who stood in his way was to be swept aside, jailed, or deported. He was convinced that he knew what was best, and not just for his own country. As Michael Kazin, one of the historians interviewed, puts it, “He wanted to be president of the world.”

Kazin himself is the author of a much-needed book for this anniversary season, War Against War, which he begins by putting his cards on the table: “I wish the United States had stayed out of the Great War. Imperial Germany posed no threat to the American homeland…and the consequences of its defeat made the world a more dangerous place.” He goes on to paint a full and nuanced picture of the surprisingly diverse array of Americans who opposed the war. Fifty representatives and six senators voted against it; one of the latter, Robert La Follette, then began receiving nooses in his office mail. More resistance came from Socialists, anarchists, and other radicals; Emma Goldman, jailed for two years for organizing against the draft, was one of 249 foreign-born troublemakers placed under heavy guard on a decrepit former troopship in 1919 and deported to Russia. She reportedly thumbed her nose at Hoover, who was seeing off the ship from a tugboat in New York Harbor.

Remarkably, Kazin points out, the South had the highest percentage of noncooperators of any part of the country. (This seems to have had more to do with the rural/urban divide than with beliefs; many young southern men had a farm to maintain or a family to support and may have simply trusted the local sheriff not to turn them in.) Perhaps the biggest surprise in Kazin’s book is the sheer number of resisters. If you add together men who failed to register for the draft, didn’t show up when called, or deserted after being drafted, the total is well over three million. “A higher percentage of American men successfully resisted conscription during World War I than during the Vietnam War.” Several bold men and women, among them Norman Thomas, A. Philip Randolph, and Jeannette Rankin, lived long enough to speak out against both wars.

Once the Russian Revolution happened, much of the repression was carried out in the name of anticommunism. Nick Fischer’s history of the anticommunist frenzy in these years, Spider Web, is unfortunately written with little grace. For instance, he repeatedly studs a lengthy paragraph with half a dozen or more descriptive phrases in quotation marks, but then forces the reader to turn to the endnotes at the back of the book to find out just who is being quoted. However, his perspective is refreshingly original.

Anticommunism in this country, he points out, never had much to do with the Soviet Union. For one thing, it had already been sparked by the Paris Commune, decades before the Russian Revolution took place. “To-day there is not in our language…a more hateful word than Communism,” thundered a professor at the Union Theological Seminary in 1878. For another thing, after the Revolution, anticommunists knew as little as American Communists about what was actually happening in Russia. The starry-eyed Communists were convinced it was paradise. The anticommunists found they could shock people if they portrayed the country as one ruled by “commissariats of free love” where women had been nationalized along with private property and were passed out to men. Neither group had much incentive to investigate what life in that distant country was really like.

For a century or more, Fischer convincingly documents, the real enemy of American anticommunism was organized labor. Employers were the core of the anticommunist movement, but early on began building alliances. One was with the press (whose owners had their own fear of unions): as early as 1874 the New York Tribune was talking of how “Communists” had smuggled into New York jewels stolen from Paris churches by members of the Commune, to finance the purchase of arms. That same year the Times spoke of a “Communist reign of terror” wreaked by striking carpet weavers in Philadelphia. In 1887, Bradstreet’s decried as “communist” the idea of the eight-hour workday.

The anticommunist alliance was joined by private detective agencies, which earned millions by infiltrating and suppressing unions. These rose to prominence in the late nineteenth century, and by the time of the Palmer Raids the three largest agencies employed 135,000 men. Meanwhile, starting in the 1870s, the nation’s police forces began using vagrancy arrests to clear city streets of potential troublemakers (New York made more than a million in a single year). Then they developed “red squads,” whose officers’ jobs and promotions depended on finding communist conspiracies.

Another ally was the military. “Fully half of the National Guard’s activity in the latter nineteenth century,” Fischer writes, “comprised strikebreaking and industrial policing.” Many of the handsome redbrick armories in American cities were built during that period, some with help from industry, when the country had no war overseas. Chicago businessmen even purchased a grand home for one general.

By the time the US entered World War I, the Bureau of Investigation and the US Army’s Military Intelligence branch were also part of the mix, making use—and here Fischer draws on the pioneering work of historian Alfred McCoy—of surveillance and infiltration techniques developed by the army to crush the Philippine independence movement. An important gathering place for the most influential anticommunists after 1917, incidentally, was New York’s Union League Club, where Elihu Root had given his hair-raising speech about executing newspaper editors for treason.

Fischer carries the story farther into the twentieth century, giving intriguing portraits of several professional anticommunists. One, for instance, John Bond Trevor, came from an eminent family (Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt attended his wedding) and got his start as director of the New York City branch of Military Intelligence in 1919. He moved on the following year to help direct a New York State investigation of subversives, which staged its own sweeping raids, and soon became active in the eugenics movement. He was a leading crafter of and lobbyist for the Immigration Act of 1924, which sharply restricted arrivals from almost everywhere except northwestern Europe. His life combined, in a pattern still familiar today, hostility to dissidents at home and to immigrants from abroad.

What lessons can we draw from this time when the United States, despite its victory in the European war, truly lost its soul at home?

A modestly encouraging one is that sometimes a decent person with respect for law can throw a considerable wrench in the works. Somewhere between six and ten thousand aliens were arrested during the Palmer Raids, and Palmer and Hoover were eager to deport them. But deportations were controlled by the Immigration Bureau, which was under the Department of Labor. And there, Assistant Secretary of Labor Louis F. Post, a progressive former newspaperman with rimless glasses and a Van Dyke beard, was able to stop most of them.

A hero of this grim era, Post canceled search warrants, restored habeas corpus rights for those detained, and drastically reduced or eliminated bail for many. This earned him the hatred of Palmer and of Hoover, who assembled a 350-page file on him. Hoover also unsuccessfully orchestrated a campaign by the American Legion for his dismissal, and an attempt by Congress to impeach him. All told, Post was able to prevent some three thousand people from being deported.

A more somber insight offered by the events of 1917–1920 is that when powerful social tensions roil the country and hysteria fills the air, rights and values we take for granted can easily be eroded: the freedom to publish and speak, protection from vigilante justice, even confidence that election results will be honored. When, for instance, in 1918 and again in a special election the next year, Wisconsin voters elected a Socialist to Congress, and a fairly moderate one at that, the House of Representatives, by a vote of 330 to 6, simply refused to seat him. The same thing happened to five members of the party elected to the New York state legislature.

Furthermore, we can’t comfort ourselves by saying, about these three years of jingoist thuggery, “if only people had known.” People did know. All of these shameful events were widely reported in print, sometimes photographed, and in a few cases even caught on film. But the press generally nodded its approval. After the sheriff of Bisbee, Arizona, and his posse packed the local Wobblies off into the desert, the Los Angeles Times wrote that they “have written a lesson that the whole of America would do well to copy.” Encouragingly, much of the national press is not doing that kind of cheerleading today.

The final lesson from this dark time is that when a president has no tolerance for opposition, the greatest godsend he can have is a war. Then dissent becomes not just “fake news,” but treason. We should be wary.

This Issue

September 28, 2017

What Are Impeachable Offenses?

Which Jane Austen?