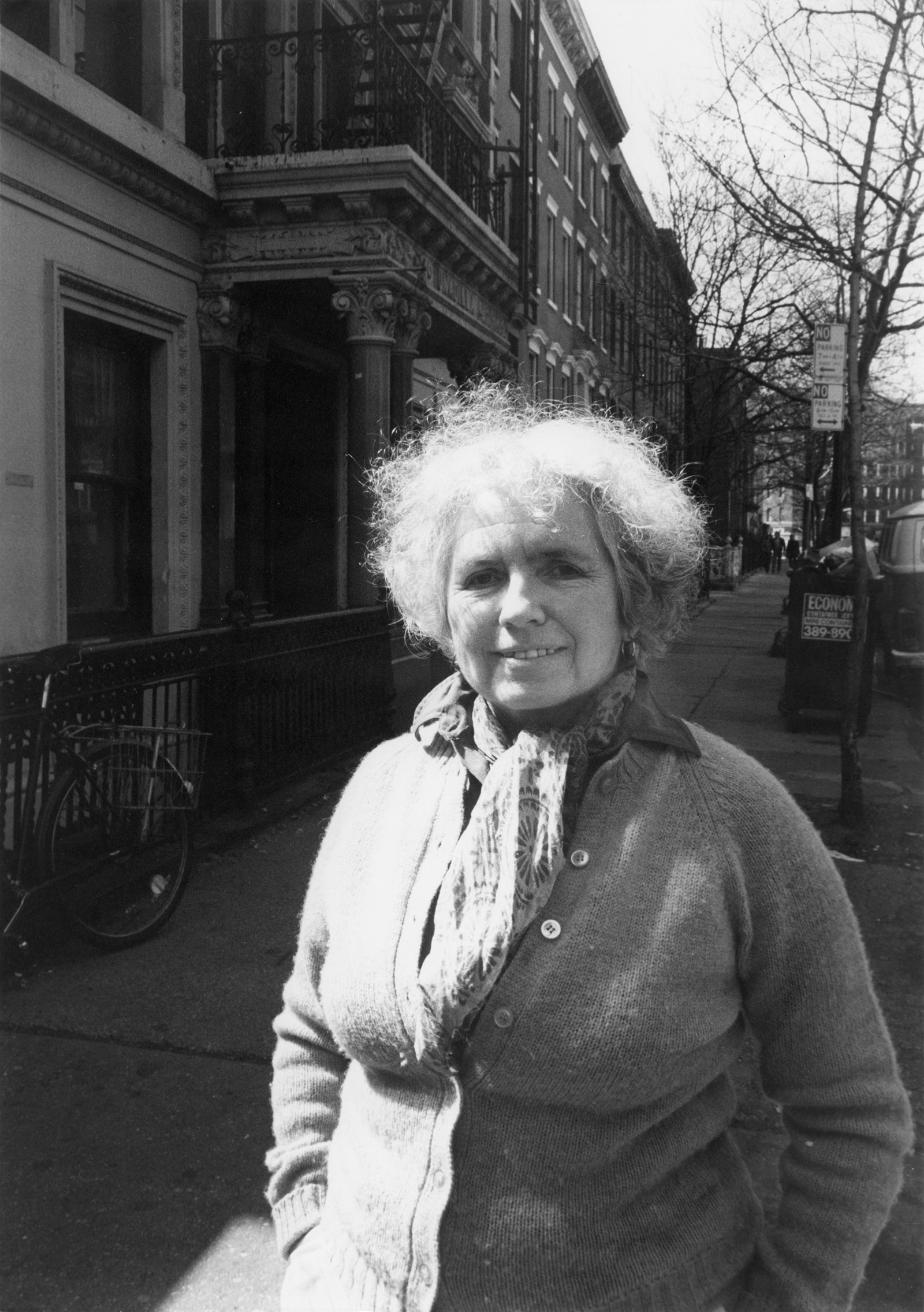

A decade after Grace Paley’s death, a new collection brings together fifteen of her most famous stories, with nineteen essays and thirty-four poems, all of them dealing with her characteristically large subjects: war, men, marriage, children, life and death. The fiction gathered in A Grace Paley Reader is peopled by lovable and profoundly eloquent characters living mostly in the Bronx, where Paley herself grew up. Her parents had come from Russia, and the family spoke Russian, Yiddish, and English.

Born in 1922, Paley went to public schools in the Bronx and then briefly attended Hunter College and the New School, where she studied with Auden, but without getting a degree. She married twice, had children, and lived the double life of a stay-at-home mother and literary figure at a time when to be both was seen as an almost impossible contradiction. Paley saw it that way herself. She worked odd jobs—secretary, superintendent of a rooming house, teacher.

During all those jobs, once I was married and after I had children, most of the day I was a housewife…. And all during those jobs and all the time I was a housewife, I was a writer. The whole meaning of my life, which was jammed until midnight with fifteen different jobs and places, was writing.

Thus Paley came to represent a category of person only then beginning to be included in the ranks of serious American literary writers—moms.

Among admired women writers of the generation before her there was a reigning intellectual, Mary McCarthy, and a southern beauty, Katherine Anne Porter; but in the late 1950s, when Paley began her career, women were otherwise scarce in the pantheon. (The activist, union organizer, journalist, and writer Tillie Olsen, a decade older, had a background and subjects similar to Paley’s. One of Olsen’s best-known short stories is “I Stand Here Ironing,” but Olsen wrote less, and was less visible, being in the far West.) Nor were McCarthy and Porter associated with vacuuming and coffee klatches and other details of female daily life. Though she was a committed political activist, Paley assumed, or faute de mieux was assigned to, the domestic realm—women’s subjects, as they were thought of. The periodical Saturday Review noted, “Grace Paley’s success should encourage every harassed housewife who harbors writing ambitions…. [She] has a husband, two children under ten, and a walk-up apartment, which she cleans herself.”

Like Paley, the women in her stories are mothers and housewives; the men are uncles, storekeepers, and old guys in the park. By being Jewish and urban, Paley also fit in with the new voices of Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Herbert Gold, Bernard Malamud, J.D. Salinger, and many others who, with their brilliant talent, access to inherited dialects, store of Yiddish folklore and jokes, local references, and the shadow of the Holocaust, had come to have a preeminent place in American literary writing. Paley, with her special brio, was a welcome addition to this assembly of voices, and her first collection in 1959, The Little Disturbances of Man, was reviewed favorably by Roth, who praised its comic and uninhibited “understanding of loneliness, lust, selfishness and fatigue… Grace Paley has deep feelings, a wild imagination, and a style [of] toughness and bumpiness.” Also, she had a perfect ear for the vernacular and cadences of her native Bronx; and in that sense she was a regional writer as well as, it could be said, an ethnic one.

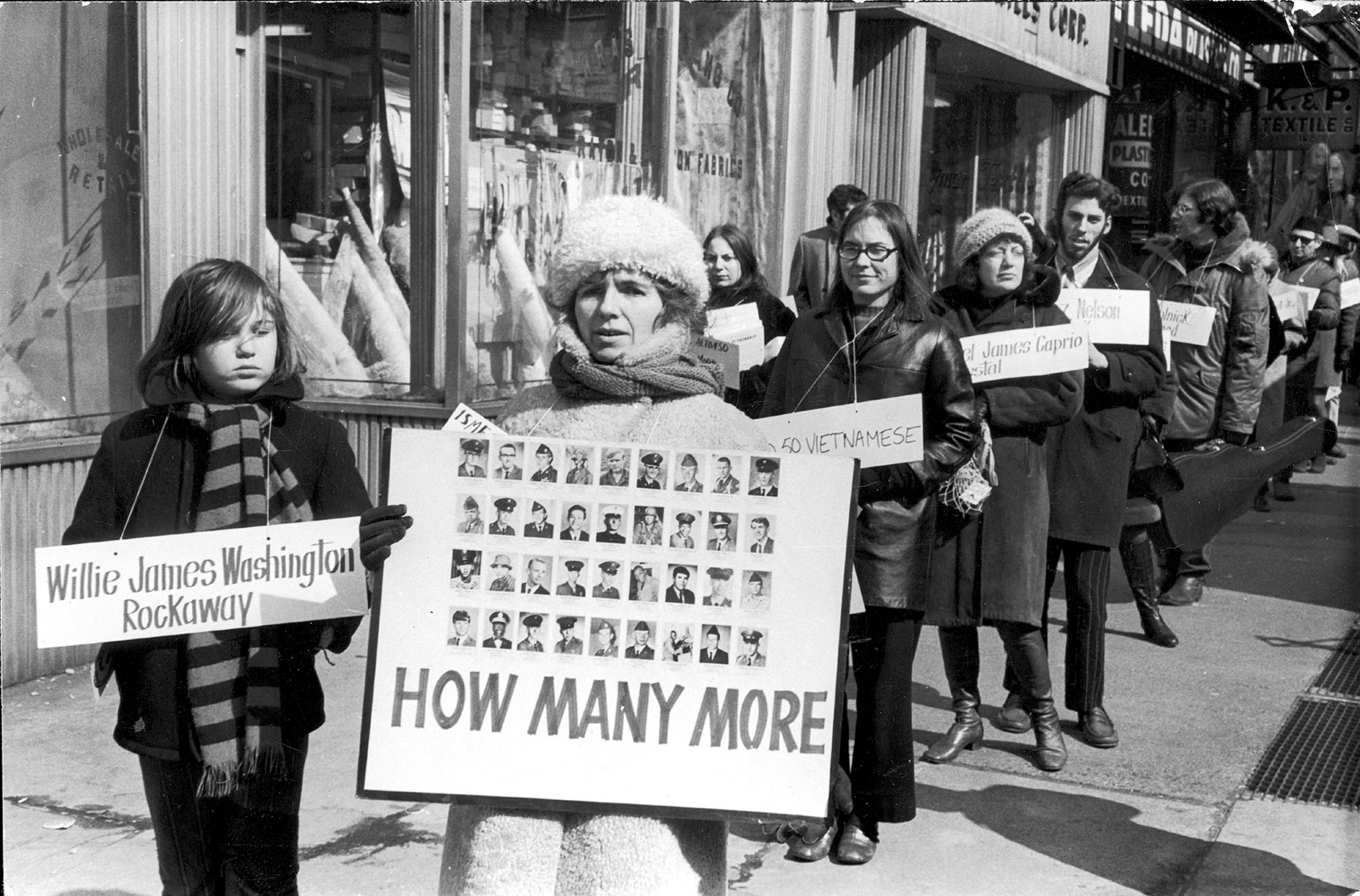

McCarthy and Porter were also politically engaged. But this new collection reminds us that Paley, despite her view of herself as writer/housewife, was not so much a writer who drifted onto political subjects from time to time; she was a full-time activist and moral leader who happened to be gifted at writing. Paley’s political concerns, among them the usual—the bomb, capitalism, Vietnam, and women’s rights—are made explicit in the essays printed here. In them she recounts her participation in various political actions and protests, including the Wall Street Action in 1979 (anti-nuclear), the Trident nuclear submarine demonstration the same year, the Women’s Pentagon Action in 1980 on the same subject, the Seneca Women’s Peace Encampment in 1983, the Mobilization for Women’s Lives in 1989 (organized by NOW in behalf of the Equal Rights Amendment), and demonstrations against intervention in the Middle East in 1990.

An essay called “Cop Tales” exemplifies her contradictory stance of activist/writer—she condemns the violent way police use their power and at the same time sympathizes with their personal concerns. At the Wall Street Action, she remembers,

the police were blocking us…. [One] cop from Long Island worried a lot about the Shoreham nuclear power plant. “Can’t do anything about it,” he said. “They’ll build it. I hate it. I live there. What am I going to do?”

Paley reflects: “That could be a key to the police, I thought. They have no hope…. They’re mad at us because we have a little hope in the midst of our informed worries.” Later she describes an incident from the previous year in which a state trooper smacked a “black youngster, about twelve…on the back of the head” and called him a “little bastard.”

Advertisement

In “The Illegal Days,” she writes with unambiguous dislike about anti-abortion activists:

These guys who run at the clinics…are point men who make the noise, and false, hypocritical statements about human life, which they don’t much care about, really. What they really want to do is take back ownership of women’s bodies.

Beside activities in America, Paley’s principles took her to Hanoi, San Salvador, Chile, and Nicaragua. When she was arrested for some of her political protests, she wrote from jail. In 1994 she remembers a time when she

had been sentenced to six days in the Women’s House of Detention, a fourteen-story prison right in the middle of Greenwich Village, my own neighborhood. This happened during the American war in Vietnam, I have forgotten which important year of the famous sixties.

To reread Paley is to reexperience the activism and excitement of the 1960s, their energy and perhaps naive optimism; her essays quiver with indignation and faith. Many, even most, of the principled stands she takes may seem self-evident in hindsight but were disputed at the time she wrote about them, like her opposition to the Vietnam War, and even the bomb. Yet one can’t help thinking that more time writing might have been a better employment of her talent.

Her fiction was certainly a means to express her political views. Sometimes these were unexpected. She was early to condemn Gerald Ford’s decision, in 1975, to authorize the mass evacuation of Vietnamese children to the US and other countries, where they were subsequently adopted by new families. Over ten thousand Vietnamese orphans and abandoned children were loaded on planes (one of which crashed, killing seventy-eight kids). Paley called Operation Babylift a “cynical political decision by the Ford administration” and by self-interested parties—adoption agencies and airlines and people carried by impulsive sentimentality. Along with Paley’s essay on the subject, “Other People’s Children,” the book prints a defense of the babylift by a reader of Ms. magazine, where Paley’s essay appeared, who had adopted four Vietnamese orphans, and a further rejoinder by Paley. Some will find Paley on the losing side of this exchange, which does expose the occasional hard-heartedness of the principled.

Of course in one way, Paley’s activism and her writing about it may seem a bit dated. She might as well be encouraging votes for women or repeal of the Volstead Act, which enforced prohibition. In the 1960s, people believed we could change things. The country has moved on; we have new wars now, a new finger on the button. Yet many of the concerns underlying the issues Paley so energetically, passionately, and wittily deplores and protests—the bomb, prison conditions, the oppression of women—are still present today. To look on the bright side, among the many pleasures of Paley’s work is the reassurance it offers that, just as we survived the events of those years, by analogy, we may yet survive the things that menace us now.

In his long, interesting introduction to the new collection, the writer George Saunders makes a case for Grace Paley as avant-garde: “I’d always thought of Paley as a realist, but immersing myself again in her work I find that she is actually a thrilling postmodernist,” he writes:

What I mean by this is that, as you read a Paley story, you will find that it is, yes, set in our world (New York City, most often) and that, O.K., it seems concerned with normal enough things (love, divorce, politics, a day at the park) but then you will start to notice that the language is…uncommon. Not quite of this world.

Some readers will be reminded instead of the avant-garde of the 1930s—think of the wisecracking films and the stylistic mannerism of John Dos Passos, say, with his capitalized letters and italics and his political themes. Paley has an entertaining and wise essay about writing itself. Number thirteen of her writing maxims (there are fifteen) says:

Don’t go through life without reading the autobiographies of

Emma Goldman

Prince Kropotkin

Malcolm X

Among her other rules:

1. Literature has something to do with language. There’s probably a natural grammar at the tip of your tongue. You may not believe it, but if you say what’s on your mind in the language that comes to you from your parents and your street and friends, you’ll probably say something beautiful.

Her characters have lots to say—wonderful lingo and plenty of joie de vivre despite their rough lives and poverty. They are rowdy, argumentative, and funny, making us laugh with an unexpected word or surprising reaction. In “An Interest in Life,” her character Virginia’s husband is joining the army. Virginia, telling the story, quotes her neighbor Mrs. Raftery:

Advertisement

“If that’s the case, tell the Welfare right away,” she said. “He’s a bum, leaving you just before Christmas. Tell the cops,” she said. “They’ll provide toys for the little kids gladly….”

She saw that sadness was stretched worldwide across my face.

The image of sadness stretched worldwide across a face resembles, in Paley’s writing, a smile.

Her poetry too is most often about the world. In her essay “Of Poetry and Women and the World,” Paley discusses a subject that particularly interests her: the chasm between writing by men on “manly” subjects like war and writing by women on “womanly” subjects like housekeeping—the difference in the way they are valued, the way male subjects are considered important, the definition of art, while the subjects about which women were expected to write are demeaned with terms like “chicklit” or “women’s fiction.” She goes a bit farther, to deplore and attack the things men have been “taught to be excited and thrilled” by:

There’s a lot of difference between my life, there’s a lot of difference between my ideas, between my feelings, between what thrills, what excites me, what nauseates me, what disgusts me, what repels me, and what many, many male children and men grownups have been taught to be excited and thrilled and adrenalined by.

She might also have been talking about contemporary cinema, much of which appears to be aimed at boys of fourteen. Paley brings up the subject of male violence in her poetry, too, as in “Is There a Difference Between Men and Women”:

oh the slave trade

the trade in the bodies of

women

the worldwide unending arms trade

everywhere man-made

slaughter

By which she means made by men, not women. Her tone is impatient, the language direct, often moving, in its universal concerns. Her poetry may be less well known than her prose, but it is preoccupied with the same issues, as here, death:

One day

one of us

will be lost

to the other

Many of the people in Paley’s stories are familiar from sitcom and stage. Only a few of them are memorable in themselves, and only a few involve us in their personal stories, for example Iz Zagrowsky, the pharmacist in “Zagrowsky Tells,” whom Saunders describes in his introduction as “intermittently racist.” Zagrowsky’s mad daughter has a “little brown baby. An intermediate color. A perfect stranger,” whom he first resists but eventually loves. A principal charm of Paley’s characters lies in their clean and honest but colorful use of language, and their willingness to enact her views and maxims, for instance, in “The Long-Distance Runner”: “It’s one of my beliefs that children do not have flaws, even the worst do not.”

For all the linguistic fireworks of their voices, some of Paley’s characters have a certain generic quality. One exception to this is her memorable alter ego, Faith Darwin, who appeared in each of her three collections and is usually taken to be autobiographical. A writer’s personal qualities always shine through her literary surrogates, and it’s Paley herself we love above all, the more so in that she doesn’t disguise herself very much, and we so admire the tough, funny, resigned, and philosophical woman we feel her to be. Faith might wear a new hat or change husbands, but Paley, behind her, stays the same in all her work.

The present volume has a number of Faith stories, which express views that are presumably Paley’s:

I’m against Israel on technical grounds. I’m very disappointed that they decided to become a nation in my lifetime. I believe in the Diaspora. After all, they are the chosen people. Don’t laugh. They really are. But once they’re huddled in one little corner of a desert, they’re like anyone else.

In the same story, “The Used-Boy Raisers,” Faith’s husband and ex-husband, Livid and Pallid, are

astonished at my outburst, since I rarely express my opinion on any serious matter but only live out my destiny, which is to be, until my expiration date, laughingly the servant of man.

This makes us laugh—opinionated Grace, so pointedly a lot more than that. It’s hard to think of another writer who has been admired for her virtuous, cheerful, and positive character as much as for her work. How sad not to hear Grace Paley’s voice today on all the many new developments that would enrage and provoke her.

This Issue

October 12, 2017

Splendid Isolation

The Art of Wrath

The Chinese World Order