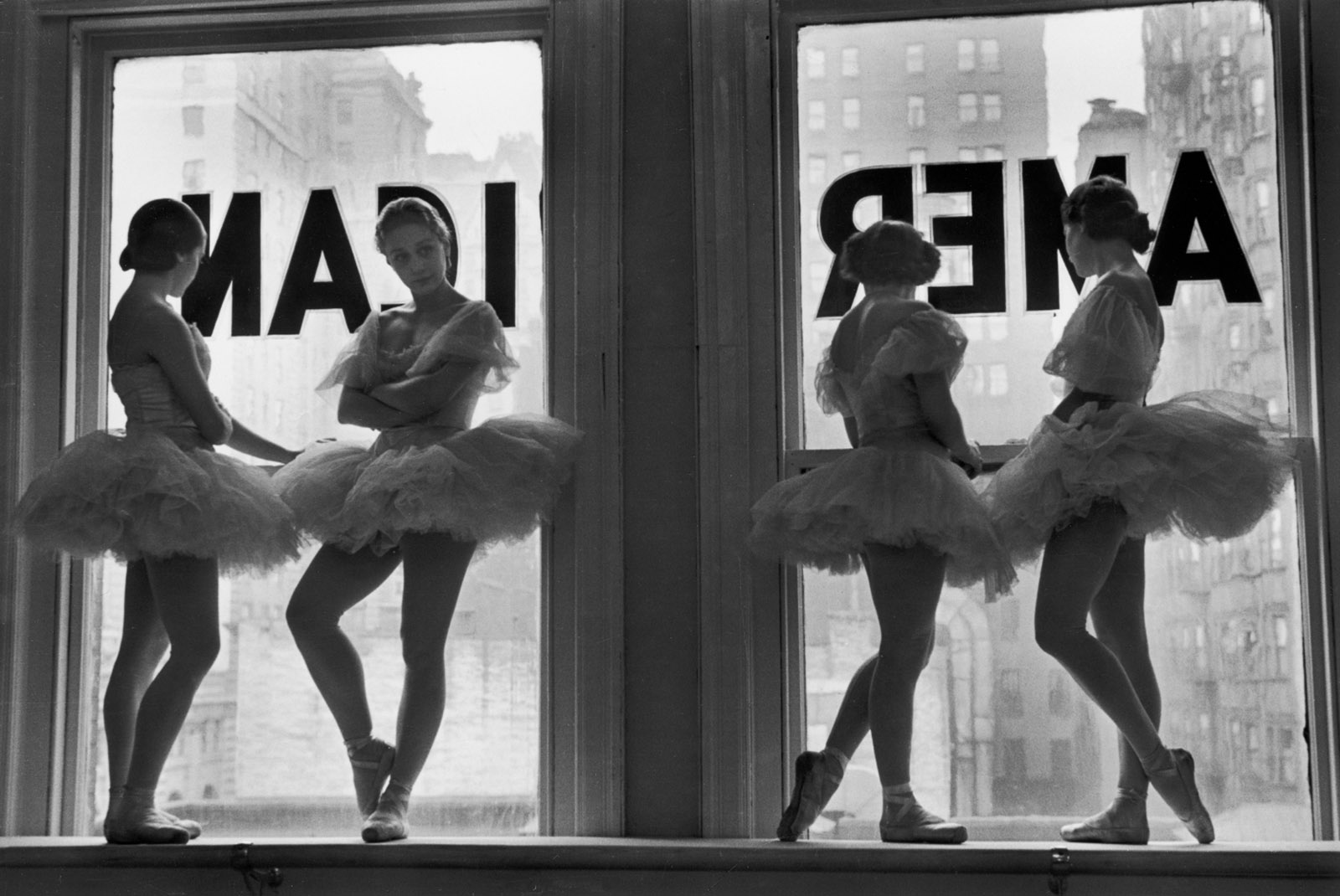

On March 14, 1934, in New York City, George Balanchine began working on a new dance set to Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings, Op. 48. He had arrived in the United States from his native Russia via Europe some five months earlier, and had just taught a morning dance class at the School of American Ballet on the fourth floor of the Tuxedo Building at 59th Street and Madison Avenue. He and Lincoln Kirstein had founded the school that January, and they had a small following of students. Everything was new: Balanchine barely spoke English, barely knew Kirstein, and barely knew his American dancers. Serenade would be his first American ballet. As the class ended, one dancer later recalled, Balanchine climbed onto the “watching bench”—a stool that allowed him a vantage point over the dancers—and stretched his arms invitingly toward them with open palms. He quietly dismissed the men and asked the women to take a break and return in fifteen minutes ready to work.

When they were all gathered, Balanchine nodded to the pianist, his fellow Russian émigré Ariadna Mikeshna, and turned to the sweaty young women in leotards, tights, and practice skirts leaning nervously on the barres. They were teenagers at the peak of health; he was thirty, fighting tuberculosis, and had recently lost the use of one lung, the consequence of living through the brutalities of World War I, the Russian Revolution, and the Russian civil wars during his youth. He graciously approached each dancer, took her by the arm, and escorted her to a spot on the floor. There happened to be seventeen women in class that day, so he made a pattern in the large studio for seventeen: two perfect diamonds of eight, with a single dancer at the point joining the two formations. From the front, every dancer could be seen—like an orange grove in California, he later liked to say.

As they stood in their places, he started to talk. In pidgin English, he told them something of his Russian past. He was a ten-year-old student at the Imperial Theater School when World War I began, and only thirteen when the revolution erupted in 1917. He left for Europe in 1924. A decade later in New York, the memories still haunted him: gunfire in the streets, scavenging for food, killing and eating cats, and freezing in subzero temperatures, not to mention the dead bodies piled in the streets as the war and revolution took their toll. He told his students about the small dance company he had started in the midst of it all, and about leaving for Berlin and Paris and working with Sergei Diaghilev. He talked anxiously about Germany and Hitler, much on everybody’s mind in 1934, and about the “Heil Hitler” salute. And he showed his young American dancers how to stand facing forward and to raise their right arms straight up, but then to soften the pose by turning their arms and heads softly to the side, gazing up at their hands.

Among later generations of dancers, some thought this story of Serenade’s first day was apocryphal, and Balanchine even liked to joke about it sometimes—“give it a ‘Heil Hitler,’” he mischievously said to one baffled dancer in the 1960s. Lincoln Kirstein kept a diary and reported on that March day in 1934 that Balanchine had told him his head was “a blank,” and asked if Kirstein might pray for him. He was composing, Kirstein noted, “a hymn to ward off the sun,” and Kirstein can perhaps be forgiven for later transcribing his own tight handwriting in thick black ink as “a hymn to ward off sin.” In later accounts and for most dancers, Serenade was simpler than all of that. It was a serenade, after all, and it naturally began with women in the moonlight, hands raised to shield their eyes from the rays of light beaming in from downstage right. Balanchine told one dancer it was the light of God, too bright for human eyes to bear.

What followed was famously improvised with the dancers as they worked in the studio in those early weeks. That first day there were seventeen, so Balanchine opened his dance with seventeen; another day only nine came to rehearsal, so he made a dance of nine; then six, so six; then one was late—and so in a later repeat of the opening formation, one girl arrives late and finds her way through the other sixteen like a woman lost in a forest of trees. As the final phrase of the movement begins, she takes her place and raises her arm to the moon to join them. On another day in the studio a girl fell, and her fall became a crucial dramatic moment in the choreography, too. For subsequent dancers, myself included, these incidents incorporated from life made us feel the presence of the first dancers, as decades later we reenacted their slips and falls.

Advertisement

The ballet didn’t stop changing. In the years to come, Balanchine made important revisions in the choreography, costumes, sets, and music. He added, cut, and rearranged well into the 1960s, when Serenade finally settled into the form that we know today—although even then he continued to adjust and rehearse the ballet personally until he was too old and sick to continue. For Balanchine, Serenade was a lifelong project and a constant companion. He had known and loved the music as a child, and had seen Michel Fokine’s ballet Eros (1915), which used the same score, in Russia during his youth.

And Serenade was with him at important moments in his life: he staged it at the Paris Opera just after World War II in 1947, and it was featured in the founding season of the New York City Ballet in 1948. When Balanchine’s company toured the USSR in 1962, at the height of the Cuban missile crisis, the seventeen dancers stood in their opening pose, tensely waiting and fearful that the audience might storm the stage; but when the curtain went up on the women in the moonlight, the entire house rose to its feet in ovation. And during the Tchaikovsky Festival at the New York City Ballet in 1981, two years before Balanchine’s death, Serenade was present too. It was there at the beginning and it was there at the end.

Serenade begins with music in a darkened theater. The curtain is down, and the audience listens to the opening phrases of Tchaikovsky’s profoundly lyrical score. Behind the curtain, the seventeen dancers are listening too, and when the curtain rises they are there, hands raised to the moonlight. They do not move. Together, everyone listens some more. They sense one another, and when the time comes they move simply and quietly in unison to the slow, ascending notes of Tchaikovsky’s opening theme.

First the wrist breaks, and the raised arm—as if “hand is tired,” Balanchine apparently told them that day—slowly traces a path to the brow. The hand then moves down and folds across the chest in half-death pose—a fleeting thought—head and eyes averted. It falls again, this time to a balletic first position, both arms low and circled, a classroom pose for his students. From there, the dancers, still moving in synchrony, all point a foot to the side as their arms lift with a breath. Finally, legs and arms close to ballet’s “home” fifth position, and in a sweeping gesture all seventeen women raise their arms through ballet’s first position and open them wide to the side, palms up, chest and eyes raised. Everything suspends for a moment over this spiritual image in the half-light. Then the beat falls and they begin to dance. It is often said that this opening sequence is symbolic: women moving through ballet’s basic positions and becoming dancers. But in practice it looks and feels even bigger than that: dancers becoming spirits—and witnesses to their own transformation in the dance to come.

Serenade has no story or narrative. It is internal—inward, like the music, and more of a prayer or ritual than a theatrical spectacle. It is a dance of women—two men appear briefly as love objects, and four others, “the blueberries,” as they are fondly called, for their blueish costumes and lumpen utility, enter briefly but just as quickly they slip back into the wings. The women are the ballet’s main subject, and they move together, break apart, recombine in twos, threes, sixes, eights, nines, sixteens, as if blown by a strong wind in swirling patterns that seem to carry them through the dance. “We ran and ran and ran,” as one dancer put it. They rarely lose sight of one another and move together seemingly effortlessly, arms enlaced or around waists, hands offered and taken, moments of call and response. Even when a woman dances alone she is still “one of us” and folds back again into the ensemble.

In the early years, the solo moments were divided among the strongest of the seventeen; later variously one, three, four, or five soloists shared them. Balanchine eventually designated three female leads: the “Waltz Girl,” the “Russian Girl,” and the “Dark Angel,” as they came to be known. The point was nonetheless always the same: there was no hierarchy in the little society that Balanchine assembled in Serenade. To some American commentators this made the ballet seem democratic—a republic of women.

Advertisement

The dances of Serenade have very few traditional steps—“I was just trying…to make a ballet that wouldn’t show how badly they danced,” Balanchine later remarked, referring to his poorly trained students. But the stamina and full-bodied sensuality that the ballet requires are unmatched in the dance repertory. The running, swirling, off-balance, nonlinear, and circular movements that swing the body with centrifugal force into a kind of bent space are anything but classical. The point is never symmetry or control. It is, instead, relentless space-devouring momentum. “What are you saving it for?” Balanchine later liked to ask his dancers. “You might be dead tomorrow.”

There is no story, but there is drama. Early in the first movement, Sonatina, a girl falls, as she did in rehearsal that day. As Alastair Macaulay has shown, a surviving film fragment from 1940 tells us that in at least one early production, she lay corpse-like on her back, arms folded across her chest. Today, she lies collapsed in a pile on the floor as twelve women circle around like a Greek chorus and perform a balletic choral song for her. She revives and moves on.

As the Sonatina ends, the opening theme returns, and the women find their places, arms raised to the moon. The “girl who was late” enters and takes her place too, but already the pattern has broken. Instead of the women all performing the opening ritual together, the other dancers turn and walk deliberately, rhythmically, off the stage, leaving the late woman to perform the ritual alone. A man appears, walking through the departing ranks of dancers, and approaches the woman. They are alone together on stage as the Waltz movement begins. The couple dance a simple waltz, full of hesitation and embrace, as if they are running, chasing, fleeing through each other’s arms in the rush of life. This woman is our Waltz Girl and she becomes the central figure of the ballet—not a character or an actor, but instead an everywoman. Everything in the ballet happens to her. But for now they are just waltzing, and the stage fills and empties as the dancers join and depart until the movement ends and we reach the Russian dance.

The Russian Girl now takes the lead. The movement begins slowly and intimately with five women who perform an inward, almost communal dance, hands gently offered and taken, or circled together backs to the world. This intimacy then opens and builds to a fantastic outward kaleidoscope of patterns, the stage filled with joyous dancing. Our Waltz Girl is there too—everyone is—and as the music reaches a climax we astonishingly, as in a great plot denouement, find ourselves and the dancers once again at Tchaikovsky’s opening theme. This time, however, the dancers—like the music—are just passing through this familiar moment, gesturing to it like an old memory. They move on. At this point, Balanchine gives us a surprising twist: instead of an end pose or tableau as the music comes to its dramatic final chords, the dancers race from the stage, and our Waltz Girl falls and is left alone, a crumpled body on the floor in the corner.

Here the melancholy Elegy begins. A woman—the Dark Angel—enters from the upstage corner with a man, a different man this time, an any-man to the Waltz Girl’s or Russian Girl’s everywoman. The Dark Angel is wrapped around him from behind—like destiny on his back, Balanchine once said—spooned as if they were one body. Her hand covers his eyes, blinding him. His arm extends forward to find his way, and her feet literally push and guide his steps forward. They walk together on a long diagonal toward the fallen woman. When they reach her they stop, and the angel removes her hand from the man’s eyes.

He sees, and they bend as one gently over the fallen girl, seeming to raise her up. The three of them form a pose taken directly from Antonio Canova’s sculpture Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, in which the winged Cupid bends compassionately and erotically over his beloved Psyche. Revived, the Waltz Girl rises, and they all dance. Now they are three, and other women run onto the stage and seem to fly through space, lifted for a moment in passing by the man, here and gone like evanescent images. Then the Russian Girl appears, and as the strings reach an ardent peak, she throws herself at the man in a reverse jump, flying toward him backward in abandon. He catches her midair—and the three are now four. (“I dreamed I had three women,” Balanchine once joked.)

At the end of the dance, the Waltz Girl is lying inert where she began in a pile on the floor, with the man standing over her, impassive, their passion spent. The Dark Angel places herself again like destiny on the man’s back and flaps her arms, powerful wings, purposefully behind him; her hand sweeps across his face to cover his eyes. Blind once more, he extends his arm forward, and they continue their walk and disappear from the stage.

The fallen girl rises. She sees a group of women and runs to one—“you are the mother,” Balanchine would say—and embraces her and slides down her legs, in a movement of resignation. She cannot let go, but she does. She stands and turns away from the mother as three blank-faced men—more threes—enter like pallbearers. She faces the back corner on a diagonal, and they lift her straight up by her feet, so that she is standing—still upright—high above them all, in another place and stratosphere, facing a bright light streaming in from the corner. High corners are the places in Russian homes where religious icons live. By now there are six women below her in formation. She is carried slowly through them, and as she goes, the women mount on pointe and all float slowly together, opening their arms, chests raised as they were in the opening ritual, going into the light that once made them shield their eyes. The curtain falls.

Tchaikovsky composed the Serenade for Strings in four movements: Sonatina, Waltz, Elegy, and a vigorous Russian-themed Finale (tema russo). In 1934, however, Balanchine’s Serenade had only three movements: he left out the Finale entirely and ended his ballet instead with the slower and more searching Elegy. Then, in stages from the 1940s to the 1960s, he added the Finale back into the ballet, until Tchaikovsky’s complete score was represented—except that Balanchine crucially flipped the last two movements and still ended his dance with the Elegy.

The Finale has a distinct musical character, different from the rest of the composition. It incorporates two Russian folk songs that Tchaikovsky recorded in 1869 in his collection of folk music, a project he had taken up after the freeing of the serfs in Russia, when artists were looking to peasant culture—rather than the staid aristocratic forms of the European elite—as a source of renewed vitality and national identity. His biographer David Brown writes that around the time that he was composing Serenade, he had a tense exchange with a friend who wrote to him arguing that all lasting culture is national and comes from “the people.” Tchaikovsky strongly disagreed and insisted that “we who use this [folk] material will always elaborate it in forms borrowed from Europe—for, born Russians, we are at the same time even far more Europeans.”

It is striking that perhaps the most intimate moment in the ballet comes in the quiet opening section of the Russian dance and Tchaikovsky’s first folk song: the simple ritualized offering and taking of hands among the five women, and the tight circling closeness that opens the formalities of ballet to an inner life. And when at the end of the movement a folk theme leads dramatically into an opening ascending scale—Balanchine’s dancers pause to mark the moment—the two passages seem briefly to belong to the same European musical world.

As Balanchine developed his Russian dance, he also nodded to Tchaikovsky’s folk themes by incorporating his own themes from Russian folk dance and old Imperial ballets. It is here in the Russian dance, for instance, that the previously more free-form chorus of women regiment themselves like a traditional corps de ballet in straight lines and symmetrical patterns. The Russian Girl, moreover, is a jumper and must be technically strong. Balanchine could only add her to his dance once he had trained her, and it is perhaps no accident that the first parts of the tema russo to appear in Serenade in the early 1940s were for the technically brilliant Marie-Jeanne, with whom he also became romantically involved.

Balanchine expanded the Russian dance further in the early 1960s, when his students—the ballet was by then performed by the dancers of his New York City Ballet—had finally reached, if not surpassed, the technical level of the dancers from the Kirov (formerly Mariinsky) theater, his childhood home and now his rival in the cultural cold war. In this sense, the Russian dance was an ongoing tribute to his dancers, and proof that the company he had built from Serenade on had established itself at the forefront of the art. More importantly, perhaps, by setting the Waltz and the Finale (tema russo)—Europe and Russia—side by side and ending his ballet with the Elegy, Balanchine shifted the entire emotional center of the composition. Tchaikovsky leaves us energetically on earth in the Westernized Russia he loved, whereas Balanchine’s dancers arch their backs and move into a transcendent realm.

Changes in the sets and costumes moved the ballet even more decisively in a spiritual direction. In the early years, Serenade was costumed in Grecian tunics of various kinds (in Paris there were chic gloves and hats), alluding to antiquity. But in 1952, the costumes were completely redone by Balanchine’s most trusted designer, the Russian émigré Barbara Karinska, who changed the look of the ballet dramatically. From that moment on, the women wore long, light-blue tulle skirts, recalling the otherworldly dead spirits of past Romantic ballets such as Giselle. In addition, at least from the 1970s on, the three principal women in the Elegy danced with luxuriously flowing hair, increasing the eroticism and femininity of the dance. This was a final improvised moment, probably added when the hair of one of the dancers accidentally came unpinned and fell loose in rehearsal (like a Clairol commercial, Balanchine noted).

As for the sets, there were various versions in the early years, but Balanchine disliked them all. They were soon dispensed with entirely, and the dance was performed on an empty stage with the only approximation of infinity we know: light. The ballet begins and ends with light. Not daylight, but moonlight—illuminating, pure, celestial. With only light and no sets, there are no shadows cast on stage, just as there are no shadows in the heavenly realm. The republic of women had become a republic of spirits.

The Dark Angel is an angel of fate, dark perhaps because she is seductive. Balanchine cast a tall, voluptuous woman in this role; wispier, more fragile dancers tended to be cast as the Waltz Girl. We think of angels as Christian, but they also appear in antiquity. And if angels in Catholic and Orthodox faiths are a way of showing the presence of God among men—of making the invisible visible—they are also witnesses and messengers like the choruses of antiquity, “clear and spotless mirrors” who can tell a tragic story without themselves suffering. Pure of mind and spirit, bodiless and sexless, they are a constant unseen presence in human life. Like the Dark Angel, hidden behind the man, they watch, intervene, and move mysteriously in our midst.

“You are his eyes,” Balanchine told one dancer who performed the Angel, endowing her with powers verging on the occult. Angel and man are two bodies as one, and her strong arms become eagle-like wings that wrap forcefully around him and cover his eyes in a clear gesture of possession. He is hers, and fate is a woman.

Yet it is not fate and the Angel who prevail in the end; it is love and the Waltz Girl. In Balanchine’s translation of Canova’s Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, the Waltz Girl is Psyche, who has betrayed her promises to her erstwhile lover Cupid (she has looked into his face) and to his mother, Venus (she has smelled the vapors of beauty brought from the underworld). At the moment depicted in the sculpture and brought to life in Serenade, the forbidden vapors have sent her into a deathly sleep. Cupid finds her and bends lovingly over her to revive her, raising her up in his arms in a near kiss as he embraces her breasts and she circles her arms softly around his neck; his wings rise behind him in a sign of both virility and immortality. We know how the myth ends: the gods, moved by Cupid’s love for this lost girl, give Psyche ambrosia and she too is immortalized. In Greek, her name means both “soul” and “butterfly,” and the butterfly is the symbol of the immortality of the soul.

In Serenade, Balanchine has made Cupid not one but two people. He is man and Angel, and it is man and Angel who together revive the still-mortal fallen girl. What happens next in the ballet is revealing: man and Angel separate, and the Angel walks deliberately in front of the man and the fallen girl and steps into a stately arabesque, posed on one leg on pointe, barely touching the earth. The man sits beneath her on the ground, workman-like, and reaches across the fallen girl to hold the Angel’s leg and steady her balance. Then he rotates her leg as if he is the motor in a music box, making the ballerina spin. In the first productions, with dancers in short tunics, he was a visible engine and the audience could see him controlling her motion—but once the long skirts arrived he was hidden in a mist of tulle and the Angel’s stately turn on one toe seemed to happen magically. If she controls his fate, he has devised her.

After they all dance together, he returns the fallen girl to her collapsed position on the floor, and he and the Angel move on. The girl has lost him, and she is alone. Their love—not the man, but love itself—has transformed her, and somehow she has the strength to rise and say goodbye to the mother. This is not necessarily a death. Dancers who perform the role have said they don’t feel dead at this moment; they are dancers, beautiful physical beings. Then we see her standing and floating high above the earth, surrendering to the light. She has become a butterfly.

Balanchine made ballet abstract, flat, and progressive, and his dances were embodiments of speed and urban accomplishment, ornaments to freedom and innovation. All of this is well known, but there were other revolutionary ideas at work in his dances too. As he was making ballet modern, Balanchine was also quietly building his own village of angels in New York City, and erecting a silent monument to faith and unreason, to women and spirit and beauty. It was mystical and utopian, really, an alternative vision of the twentieth century. Or as Balanchine preferred to put it with Serenade, an orange grove in California.

This Issue

December 21, 2017

Lies

Kick Against the Pricks

The Man from Red Vienna