1.

“And now, once again,” wrote Mary Shelley in her introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, “I bid my hideous progeny go forth and prosper.” It has certainly done so, but in ways, and for reasons, she could never have foreseen. Currently there are more than sixty million Google results for a search of the name “Frankenstein,” more than for Shakespeare’s Macbeth. There have been more than three hundred editions of the original novel; more than 650 comic books and cartoon strips inspired by it; over 150 fictional spin-offs and parodies; at least ninety films, including James Whale’s 1931 classic with Boris Karloff; and something like eighty stage adaptations. It is now frequently required reading in schools, and passing classroom references to “Shelley” may more likely mean Mary than Percy Bysshe (the obscure author of Prometheus Unbound). In the press the term “Frankenstein” is still standard shorthand for science gone wrong, warning of every supposed scientific “menace” from nuclear power to stem cell research and genetic modification. In short, her monster has become a modern myth.

This mythic prosperity, whatever it signifies today, was slow in coming. Mary Shelley’s original three-volume novel was published quietly and anonymously by Lackington and Co., Finsbury Square, London, in March 1818 and to little acclaim. It had already been rejected by Byron’s famous publisher, John Murray. At the time it seemed so utterly strange that its few reviewers thought it must have been written by Mary’s father, the notorious anarchist philosopher William Godwin, or possibly, according to the great romancer Sir Walter Scott in Blackwood’s, by Mary’s husband, the dangerous atheist poet. The Quarterly Review stonily observed: “Our taste and our judgment alike revolt at this kind of writing…. The author leaves us in doubt whether he is not as mad as his hero.”

If they had guessed the author was in reality a young woman, only eighteen when she began her first draft, no doubt the critical chorus of disapproval would have been even more thunderous.

It is astonishing that the book ever got written at all. The nightmare birth of the initial idea, during the celebrated stormy ghost-story competition of June 1816 at the Villa Diodati, on Lake Geneva, between Lord Byron and the two Shelleys, is well attested by Mary herself and also by the contemporary diary of Byron’s volatile medical companion, Dr. William Polidori, an expert on somnambulism. (“A conversation about principles, whether man was to be thought merely an instrument…. Twelve o’clock, really began to talk ghostly…. Stories are begun by all but me.”)

But the actual composition of the first 72,000-word draft lasted some eleven months, until May 1817, during which time Mary’s stepsister, Claire, bore Byron’s illegitimate baby secretly in Bath; her half-sister Fanny Imlay committed suicide with an opium overdose in a Welsh hotel; and Percy Shelley’s legal but abandoned wife, Harriet Shelley, “being far advanced in pregnancy” (according to The Times), committed suicide by throwing herself into the Serpentine. In addition, Mary found that she was pregnant. The manuscript of Frankenstein was delivered to the publisher just five weeks before her baby was born.

That Mary persisted in developing her story throughout these domestic dramas, as well as diligently researching such authors as Erasmus Darwin and Humphry Davy, is truly remarkable. But it is hardly surprising that painfully adult themes of birth and death, the terrors and responsibilities of parenthood, and the agonies of the outcast or the unloved suffused her youthful imagination like blood.

The 1818 edition of the novel ran to a mere five hundred copies. It was the early theatrical adaptations that popularized the story. Presumption: or, The Fate of Frankenstein was first staged at the English Opera House in July 1823 and opened to scandalous publicity (“Do not take your wives, do not take your daughters, do not take your families!”) and huge audiences. Five separate theatrical adaptations followed between 1823 and 1825, taking Frankenstein to Paris, Berlin, and eventually New York. In London, Mary Shelley herself attended in the stalls: “Lo and behold! I found myself famous! Frankenstein has had prodigious success as a drama…in the early performances all the ladies fainted and hubbub ensued!”

The hubbub, so to speak, has never really died down. Danny Boyle’s stage production of Frankenstein (with Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller alternately playing the Creature and his Creator) at the National Theatre, London, was a controversial popular hit in 2011. It was especially memorable for its opening coup de théâtre, in which the actor playing the Creature dropped buck-naked onto the stage from a huge, pulsing artificial womb and for several minutes writhed into glistening life in front of a stunned audience.

Advertisement

Adaptations as well as literary references inspired by the novel, both serious and lighthearted, never cease to bubble up. This autumn, Young Frankenstein, based on the 1974 Mel Brooks/Gene Wilder film and billed as “the new musical comedy,” opened at the Garrick Theatre in London’s West End; and another musical version appeared off-Broadway at St. Luke’s Theatre. The opening pages of Salman Rushdie’s latest novel (his fourteenth), The Golden House, introduce his mysterious protagonist, Nero Golden, with this sinister aside: “Sometimes, watching him, I thought of Dr. Frankenstein’s monster, a simulacrum of the human that entirely failed to express any true humanity.” But that of course is a remark inspired by film images rather than the novel. For the debatable nature of “true humanity”—and whether Victor Frankenstein (never Doctor in the novel) or his Creature can best express it—is precisely the dilemma of Mary’s original fiction.

2.

After two hundred years, how exactly are we to go back to the novel itself, as distinct from its proliferating, multimedia myth? The highly complex literary structure, after all, consists of three overlapping autobiographies—by the explorer Robert Walton, by Frankenstein, and by the Creature himself—each cunningly nested one inside the other, each with a different voice, a different timeframe, and a different view of the historic experiment and its terrible consequences. It seems to combine several genres at once: grim gothic melodrama, exuberant science fiction, satiric cautionary tale, passionate moral parable, and even (especially in its superb evocation of mountains and polar regions) the vivid, unreeling panoramas of a Romantic adventure story.

Frankenstein is saturated in the heroic rhetoric of Milton’s Paradise Lost, the alienated imagery of Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” and the natural magic of Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey” (all of which are actually quoted). It also clearly contains a series of philosophical debates between scientific hope and hubris, between friendship and betrayal, between love and solitude. The desperate Creature argues furiously with Frankenstein on the bleak Mer de Glace glacier in Chamonix about the reasons (and moral responsibility) for making him a female companion: “Oh! my creator, make me happy; let me feel gratitude towards you for one benefit! Let me see that I excite the sympathy of some existing thing; do not deny me my request.”

The scholarly interest in these themes, and in the shaping of the text, is comparatively recent. As Timothy Morton wrote in his comprehensive anthology, Frankenstein: A Sourcebook (2002)—sampling everything from Regency anatomy classes to contemporary gender theory—it is a new industry “that has been burgeoning since the 1980s.” For instance it is now accepted that there are at least three main versions of the novel, which though structurally similar are significantly different in language and dramatic impact. It seems that Mary was always considering how it might be improved. In 1823 she wrote: “If there were ever to be another edition of this book, I should re-write these first two chapters. The incidents are tame and ill-arranged—the language sometimes childish.”

The first version was written at great speed in two Genevan notebooks, largely during the winter of 1816–1817, but not published until 2008 in a meticulous edition edited by the Shelley scholar Charles E. Robinson. The style is bold and direct. It probably began as a “short tale,” with a draft of the famous opening: “It was on a dreary night of November, that I beheld my man completed.”

The second, beginning and ending with Robert Walton’s Arctic expedition, was carefully revised by Mary, lightly edited by Percy, and published in 1818. The style is richer and more digressive, and there is still academic controversy about the overall effect of Percy’s additions (about five thousand words). A re-issue of this 1818 version, with some minor changes, appeared in 1823 in two volumes, at the urging of Mary’s father, William Godwin, and was the first to be published under her own name.

The third version, of 1831, was radically revised by Mary alone, and is longer and altogether darker in tone. The idealistic young Frankenstein is subtly changed into a doomed and tortured figure. This is reflected in the new “Author’s Introduction,” which embroiders on the ghost-story competition at the Villa Diodati, links the “many conversations” held there at night with her later scientific reading (further detailed in the Shelleys’ shared Journal), and describes the single nightmare that she claims inspired her.

The 1831 introduction gives a further glimpse into the crucial birthing moment. This has become central to the popular myth of malevolent science, especially in film, with the hysterical cry “It’s alive! It’s alive!” (words that Mary Shelley never actually wrote). In the novel the first account is given with horrific clarity by Frankenstein in two short paragraphs, and then in a confused recollection by the Creature himself on the Mer de Glace. The third account now becomes that given retrospectively by the novelist in her own voice, and paradoxically it is the most memorable and disturbing:

Advertisement

I saw—with shut eyes, but acute mental vision—I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the workings of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion….His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away from his odious handywork, horror-stricken.

The fascination with this moment of dangerous birthing and the subsequent status of the Creature as an unloved or unparented child (rather than a mere monster) are characteristic of much modern, and not only feminist, interpretation.* When a Frankenstein ballet was staged at the Royal Opera House, London, in May last year (and later performed in San Francisco), the director Liam Scarlett made this acutely contemporary observation: “People have a very stereotypical view of what they presume Frankenstein to be…and actually I don’t think many people really know the heart and soul of the story. It’s essentially about love…. [The Creature] is like an infant…. He’s desperately seeking a parent or loved one to take him through the world and teach him all these things.”

3.

So how can we best respond to Mary’s hideous progeny now, after so many bewildering transformations? Two new annotated editions of the novel directly address the question, but in strikingly different fashion and with strikingly different results. (Neither should be confused with the classic Harvard University Press Annotated Frankenstein of 2012.) The first, edited by David Guston and others (which we can call the MIT edition), is described as “annotated for scientists, engineers, and creators of all kinds.” It is in fact largely addressed to STEM students and presents the plain 1818 text barnacled with an almost continuous series of footnotes beneath, all serious and some of a distinctly philosophic turn: “Who are we really? What are we made of? What is the self? What makes the creation a monster?” They are contributed by some forty writers and academics, many of whom come from scientific departments of Arizona State University (the above questions are from C. Athena Aktipis of the department of psychology). It makes for a busy symposium. But the results successfully produce “a far ranging critical conversation,” though in rather sober imitation of those original wild Diodati nights.

It is interesting to see which parts of the novel attract the most attention from these scientific commentators. The greatest clusters of footnotes seem to gather beneath the two early chapters (3 and 4) describing Frankenstein’s scientific education at Ingolstadt and his “workshop of filthy creation” (no less than twenty-two footnotes in fourteen pages). This sometimes risks becoming more of a cacophony than a conversation—Egyptian mummies, René Descartes, Scottish grave-robbing, Nazi doctors, Craig Venter and the genome project all crowd in. Yet more calmly distributed can be found excellent short pieces on robotics, artificial intelligence and machine learning, Luigi Galvani and the history of electricity, bioethics, regenerative medicine, and of course on the whole possibility of extending human capacities.

Some reflections appear less reassuring than perhaps intended. A characteristic one from Ed Finn, director of the Center for Science and the Imagination at ASU, begins: “Scientists have long aspired to improve the human body, or create new bodies, to exceed our natural biological limits. The United States military pursues a range of research areas to enhance the performance of soldiers, from powered exoskeletons granting their users superhuman strength to direct brain interfaces that would allow pilots to fly aircraft by thought alone.” It continues with references to contact lenses, pacemakers, antibiotics, genetic modification, robotics, and replicants, and ends with The Terminator and Blade Runner, and the provocative flourish, “What consequences would result from a world in which human and superhumans coexist?”

There are also long and thoughtful meditations on such subjects as Romantic attitudes toward slavery; Nature and wilderness; identity and the soul, and the special bonds of friendship and sympathy. The latter word appears more than thirty-five times in the novel, and draws attention to the profound ambiguity in Mary’s presentation of the Creature. Is he innocent or savage, human or alien, driven mad or innately evil?

For instance, when he commits his first murder, it is of the beautiful little child William Frankenstein, and it occurs apparently without premeditation and without intention. According to the Creature’s autobiography, it is part of an innocent but desperate search for friendship. (He has already discovered his own appalling ugliness, been rejected by the kindly De Lacey family, beaten violently, and actually shot at.) “Suddenly, as I gazed on [William], an idea seized me, that this little creature was unprejudiced, and had lived too short a time to have imbibed a horror of deformity. If, therefore, I could seize him, and educate him as my companion and friend, I should not be so desolate in this peopled earth.”

How far do we accept this explanation? This restless ambiguity—solitary outcast or vengeful demon?—is developed throughout the novel, pulling the reader’s sympathy first in one direction, then the other, exactly like Frankenstein’s own. It is a crucial dynamic, swinging imaginatively between the two poles of rejection and compassion. “Am I to be thought the only criminal, when all human kind sinned against me?” It is the peculiar ability of fiction to do this, not just to pose technical issues.

It is here too that Shelley is most rhetorically ambitious, drawing on the high language of Milton’s Satan, which she uses to power the great ethical debate between Creator and Creature, which reaches its dramatic climax in the scenes on the Mer de Glace. Paradoxically (and unlike all film adaptations) it is the “Monster” who now becomes the most articulate and human, producing great operatic arias of speech:

Oh, Frankenstein…Remember, that I am thy creature: I ought to be thy Adam; but I am rather thy fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. Every where I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.

Overall, the MIT edition is plain and purposeful, briefly introduced by Charles Robinson, and completed by “Discussion Questions” and seven speculative essays (notably “Frankenstein, Gender, and Mother Nature” by Anne K. Mellor and “I’ve Created a Monster!” by Cory Doctorow). Admittedly it does tend to treat the novel as a machine to think with, rather than as an imaginative experience to explore. Yet despite this pedagogic crowding, it returns resolutely to the great challenge situated at the heart of the novel, which all “scientists and engineers” might usefully consider. What is the true nature of Frankenstein’s Creature, and what duty of care does Frankenstein owe to it?

4.

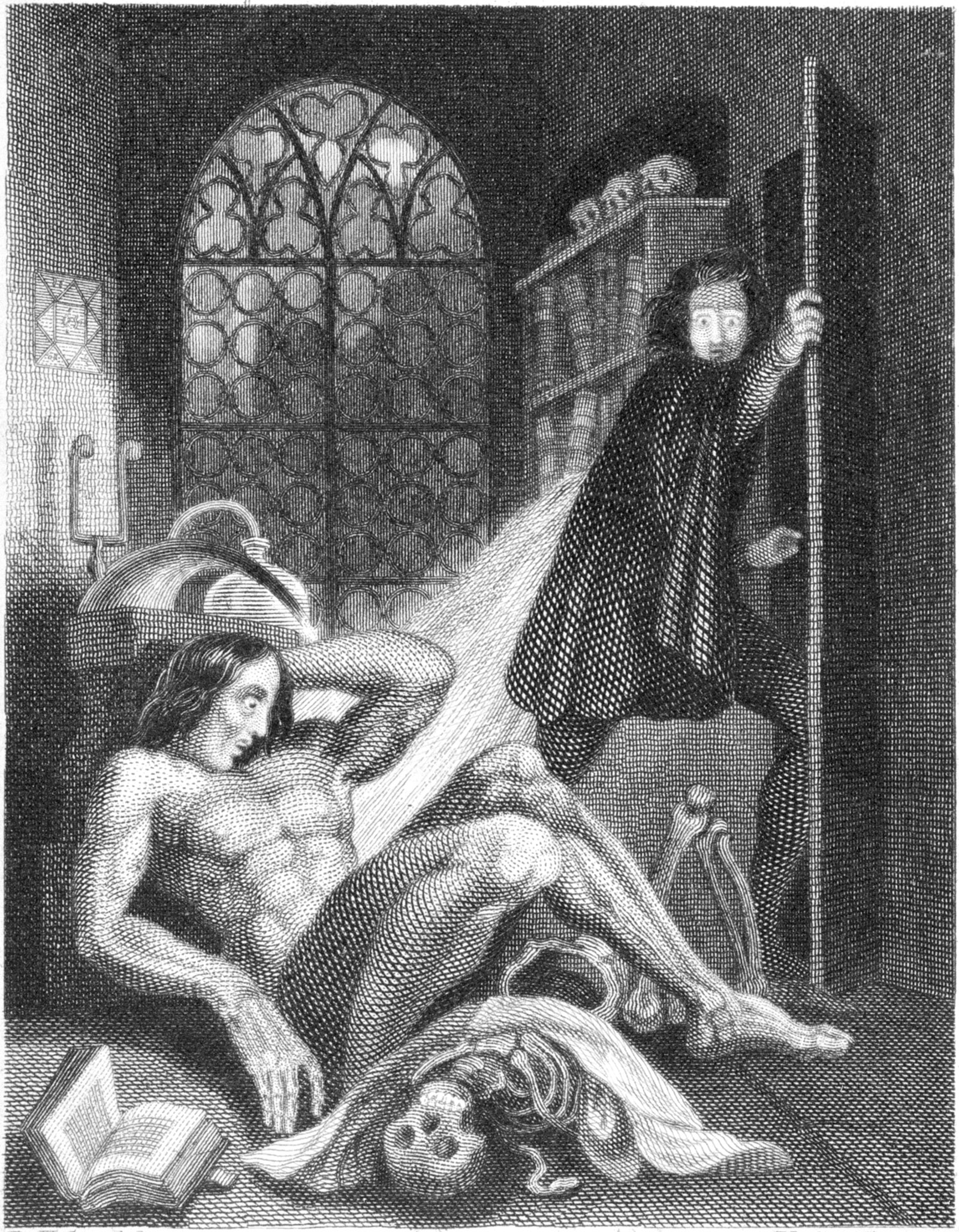

By comparison, Leslie S. Klinger’s edition is a hugely flamboyant production, rich in varied resources, often playful in style, and fabulously illustrated throughout. Klinger has previously produced annotated editions of Dracula and Sherlock Holmes (which might raise doubts about his gravitas), but the work is impressive. First of all, while also using the preferred 1818 text, he performs the scholarly task of printing all the rewritten 1831 text directly alongside in the margins, and also the so-called Thomas Text alternatives of 1823. There is a long historical introduction, and a series of essays (another by Mellor on “Genetic Engineering”). The margins are also used as a continuous running encyclopedia or hypertext, glossing most of the names, places, literary references, and philosophical ideas that appear.

Here historical and social background are considered prime. So the margins contain, for example, extensive background notes on the University of Ingolstadt; laudanum; Alpine tourism; the Vitalist controversy and the contending physicians Hunter, Abernethy, and Lawrence; Lavater’s Physiognomy; Davy’s Lectures; and Mary Wollstonecraft and her Vindication of the Rights of Woman. There are rich quotations from the contemporary Baedeker and Murray’s Handbook to Switzerland.

Altogether there are no less than a thousand of these notes, all illuminating, if sometimes wonderfully extraneous. One can relish the brilliantly concise three-page history of the French madhouse at La Salpêtrière on the basis that Frankenstein may have been briefly incarcerated in a lunatic asylum. But it seems quite hard to justify a history of golf at St. Andrew’s, Scotland; an account of the burial of Pocahontas at Gravesend, on the Thames; or the complete story of Captain Bligh and the mutiny on the Bounty (with map). The fuller story of Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost or the albatross in Coleridge’s “Ancient Mariner” might have been more relevant.

The illustrations are spectacular and abundant: portraits, facsimiles, manuscripts, engravings, cartoons, first editions, theater posters, film stills, city guides, and period landscapes. There are many surprises, ranging from Robert Hooke’s seventeenth-century Micrographia to Gustave Doré’s nineteenth-century engravings and Frank Hurley’s twentieth-century polar photographs. There is also an engaging catalog of forty Frankenstein films (“merely a selection of the more noteworthy…although ‘noteworthy’ in this genre rarely indicates a film of quality”). These start with honorable mention of Thomas Edison’s little-known fifteen-minute silent movie of 1910. Many are accompanied by their memorably lurid posters. But the critical commentaries are refreshingly dry. Flesh for Frankenstein (1974) is dispatched in a single sentence: “Warhol’s nearly incoherent film involves zombies, disemboweling, and sex.”

The danger of this cornucopia of secondary data is distraction from the novel itself. It sometimes becomes a dashing riverboat ride with an inexhaustibly loquacious tour guide pointing out the marvelous landmarks on either side. Yet the effect of supplying the 1831 text, as well as the intermediary notes Mary made in 1823, is startling. For instance, Mary realized how strange it was that Frankenstein should work so passionately and for so many months on his Creature, but never grasp how repulsively ugly it was until that crucial moment of animation. This fatal ugliness, which will become its doom, is central to the Creature’s entire destiny and the novel’s whole plotline of rejection and revenge. How could this scientific blindness, or this ethical failure to see what was under his very hands, possibly be explained?

In the notes of 1823 (the Thomas Text, a series of manuscript additions that Mary gave to a woman friend in Italy) she begins to explore a more psychological explanation for this obsessive tunnel vision. To the simple statement of the 1818 Frankenstein—“I became nervous to a most painful degree”—she now adds this: “My voice became broken, my trembling hands almost refused to accomplish their task; I became as timid as a love-sick girl, and alternate tremor and passionate ardour took the place of wholesome sensation and regular ambition.” This hysterical, traumatized, or tortured aspect to Frankenstein’s personality, with its implicit psychosexual overtones, will be developed much further in the final 1831 version, and the Klinger edition allows us to see this very well.

Mary claimed that all such changes were merely stylistic and introduced no “new ideas or circumstances.” But we now know that she had been thinking about these since 1823, and they are dramatically evident in the early chapters presenting Frankenstein’s more complex relationships with his beloved father, his bride, Elizabeth, and his great friend Henry Clerval. Above all they put deeper shadows around his education in science by Professor Waldman at Ingoldstat: “Such were the professor’s words—rather let me say such the words of the fate enounced to destroy me. As he went on I felt as if my soul were grappling with a palpable enemy.”

Shelley also transforms Frankenstein’s final friendship with the Arctic sea captain Robert Walton (which both opens and closes the novel). Walton now becomes a mirror image of a fellow scientific explorer driven to extremity: “Do you share my madness? Have you drunk also of the intoxicating draft?” There are some magnificently rewritten passages of alpine description, which emphasize the power and cruelty of Nature bearing down on Frankenstein, its “immense mountains and precipices that overhung me on every side,” and the fact that he too is driven by “the silent working of immutable laws.”

In an influential study of 1988, Anne Mellor argued that the overall effect of the 1831 changes is to make Frankenstein weaker and more deluded, “the pawn of forces beyond his knowledge or control,” at the mercy of what he now calls “the Angel of Destruction,” and that this reflects a considerable darkening of Mary’s early optimistic hope for science in 1818. Since she was then cut off from the Shelley-Byron-Polidori circle (all long dead by 1831), this may well be true.

Mellor’s new essays in both these annotated editions continue to be thought-provoking. Frankenstein’s sin and mistake, she suggests in a striking phrase, is “his failure to mother his creation.” Nature “punishes Victor by preventing him from creating a normal child.” This she considers a warning to modern geneticists about the “unintended consequences of human germline engineering.”

Yet here we are left, once more, with the enduring ambiguity of Mary Shelley’s extraordinary fiction. An alternative interpretation of the 1831 text is that Frankenstein actually becomes a more conscious Faustian figure, while the Creature becomes a more eloquent voice for rejected human rights. The scientist is less naive, and the Creature less monstrous. Both suffer more from an increased awareness of what each has done and the possibilities they have lost, as the explorer Walton tragically witnesses. His “thoughts, and every feeling of [his] soul, have been drunk up” by the tale.

Frankenstein’s original scientific ambitions were always intensely idealistic and benevolent, and this remains true in both the 1818 and 1831 editions:

Life and death appeared to me ideal bounds, which I should first break through, and pour a torrent of light into our dark world. A new species would bless me as its creator and source…. I might in process of time…renew life where death had apparently devoted the body to corruption.

With modern scientific advances in every field, but especially in medicine, surgery, and biotechnology, we may wish to rethink the lurid myth and reread this prodigious, ever-youthful novel in a new way. As Frankenstein gasps to Walton with his final breath, in both 1818 and 1831: “I have myself been blasted in these hopes, yet another may succeed.”

This Issue

December 21, 2017

Lies

Kick Against the Pricks

The Man from Red Vienna

-

*

See for example the varied perspectives provided by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, “Mary Shelley’s Monstrous Eve” (1979); Mary Poovey, “‘My Hideous Progeny’: The Lady and the Monster” (1984); Anne K. Mellor, “Possessing Nature: The Female in Frankenstein” (1988); and Bette London, “Mary Shelley, Frankenstein and the Spectacle of Masculinity” (1993). All reprinted in Frankenstein: Norton Critical Edition, 2012. ↩