The vision of babies that recurs in my work is not accidental. My images take the shape of my obsessions.

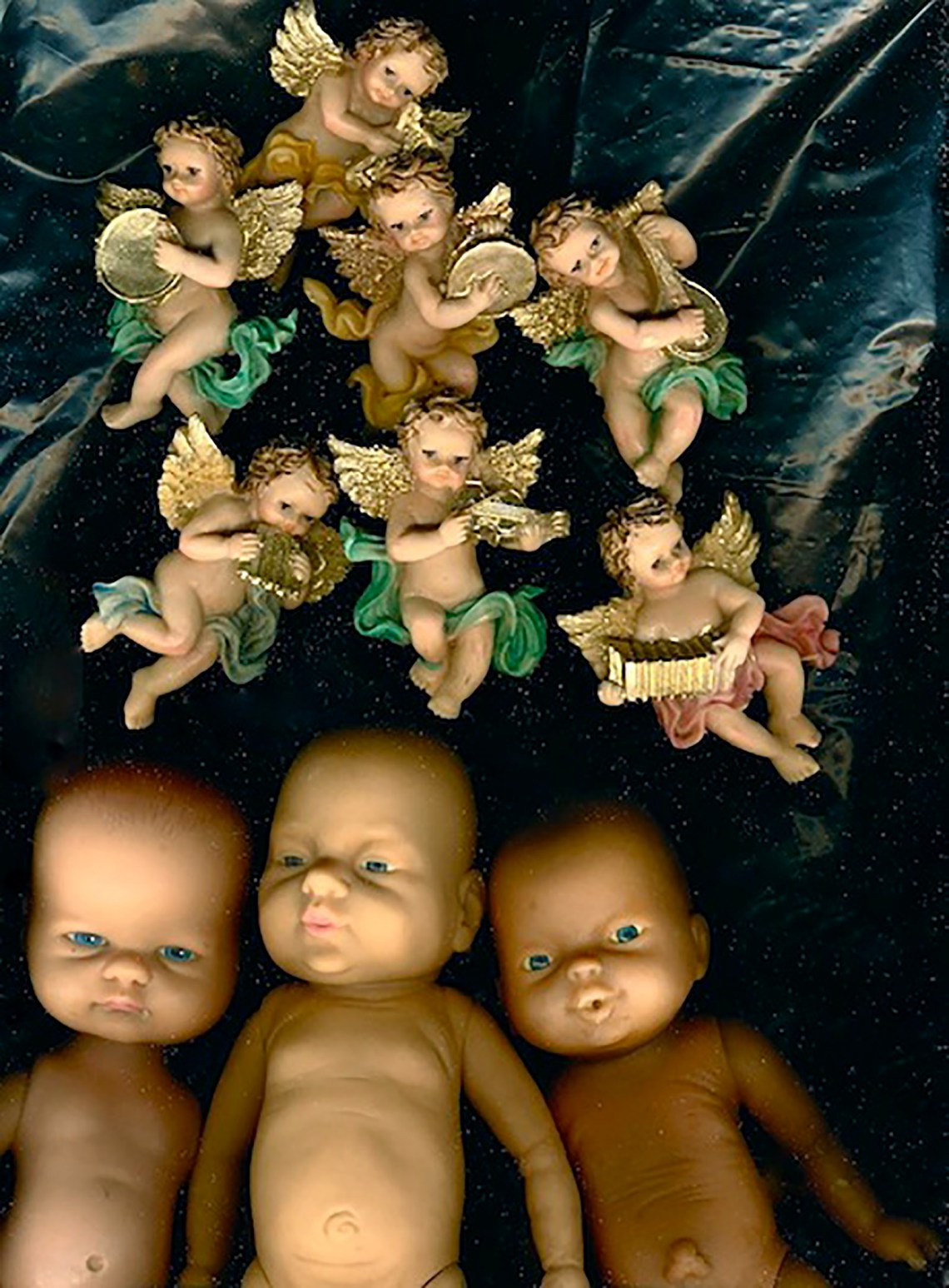

As a child, I enjoyed playing with my sister’s dolls—behavior that was tolerated until I reached age six. The dolls were taken away, but my interest in them was not. As an adult, I began a small collection of the oddest “what-were-they-thinking?” toys I could find. My chief creative interest has always been painting, but when I got a night-shift job at a major publishing house, with unfettered access to Xerox machines, my dolls took on new lives as copier art props.

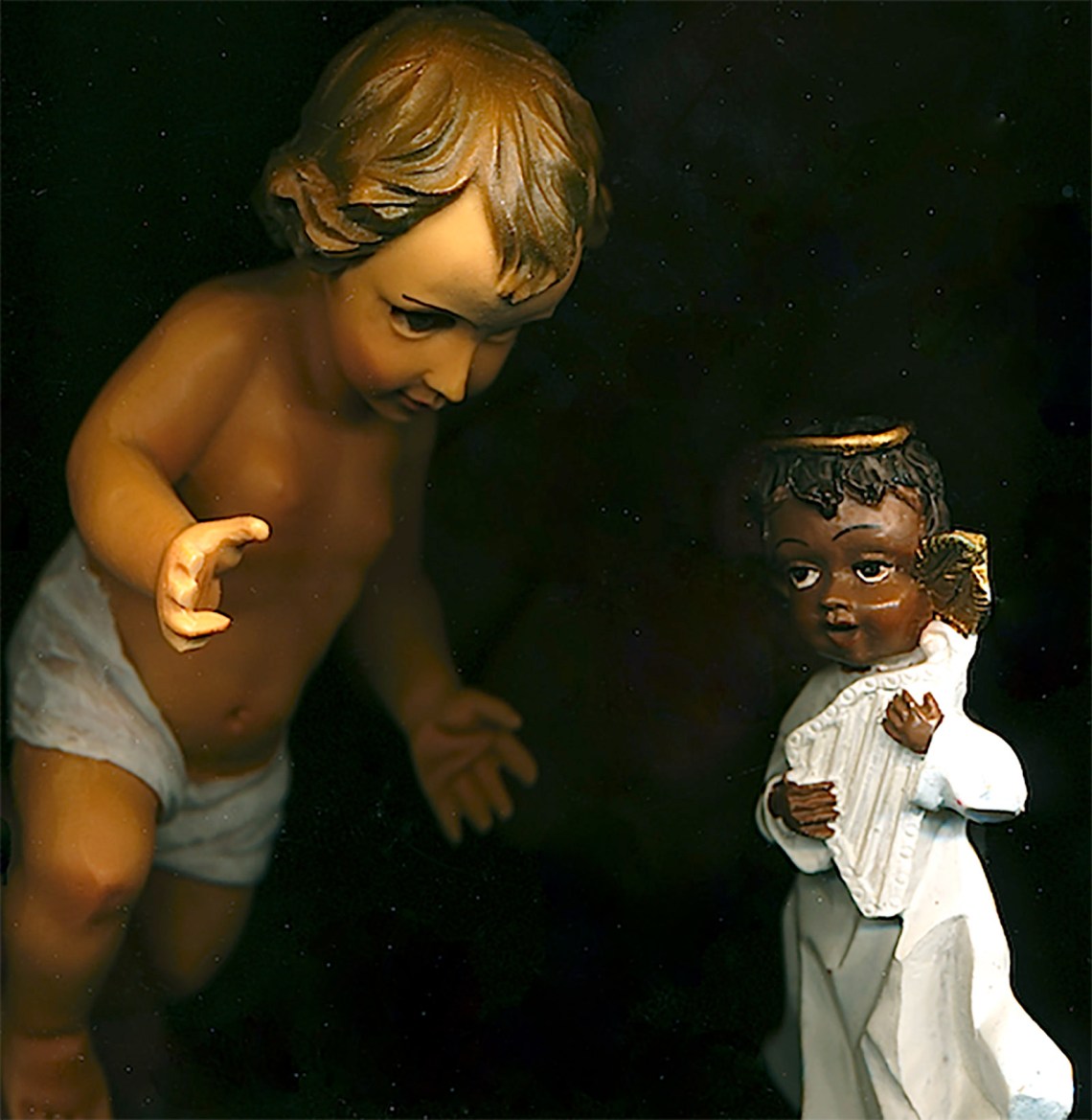

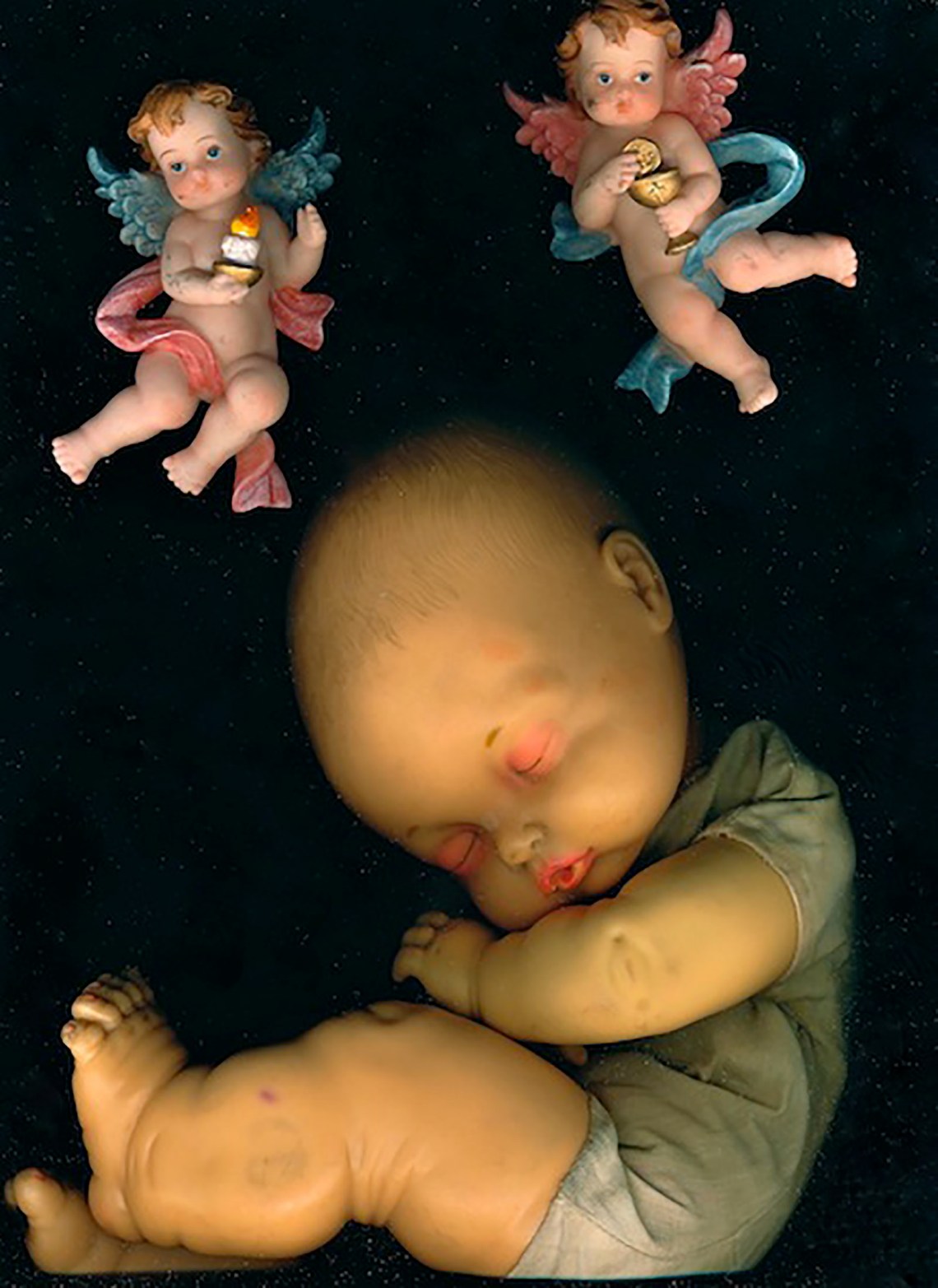

Narrative tableaux based on overwrought religious imagery, especially as it intersects with consumerism (such as mass-marketed holidays), became my specialty. I was long ago downsized from the publishing house, so I continue to create images on a home scanner, and now also use computer animation applications.

Just as for Freud, ancient objects became metaphors for primal states, so for me, the accessories of childhood unlock an archaeology of the mind. The Xerox or printer scan is an ideal medium for this. The light is pure Caravaggio, while the glass plate becomes the perfect stage for dreamlike juxtapositions.

My love of the doll imagery of Joseph Cornell and James Ensor, for instance, is partly born of the sense of childhood kept alive. Their work preserves the uncanny perception of dolls’ attractive creepiness, a seeming consciousness.

Received ideas are unwittingly incarnated in the manufactured rubber objects and identities emerge. Using artificial breasts, snakes, naked baby-dolls, and other props, I give that consciousness expression, satirizing what was unwitting and making it manifest and visceral: a weird vision ripe with resonant gender tensions, aesthetic hierarchies, neuroses, and, perhaps, spirituality.

I find that when people see my photocopy-based art, they laugh and squirm at the same time. They feel the release of humor, but they also feel that such things shouldn’t be funny.