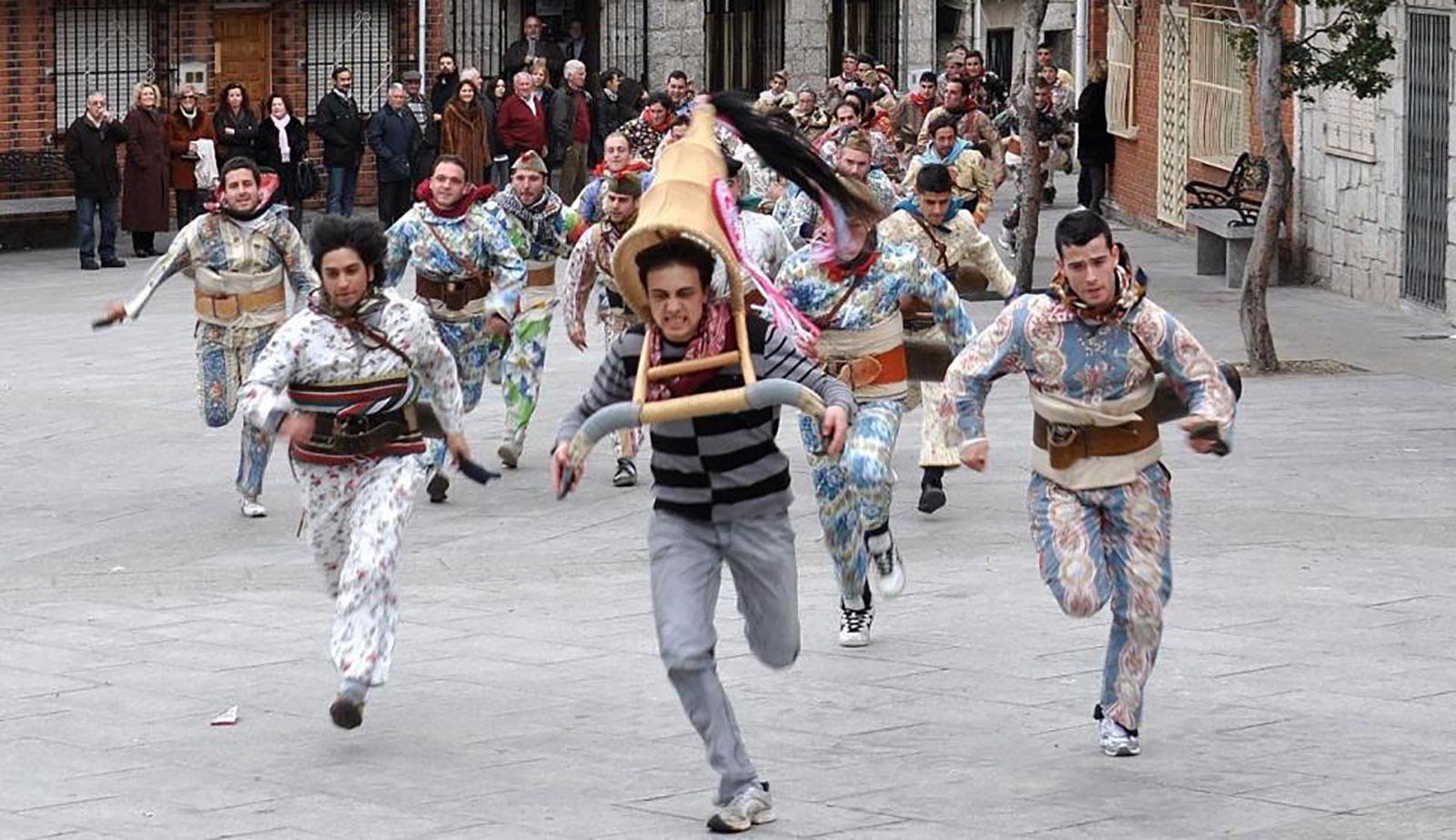

Forty-odd bachelors in flowered pajamas, tubular bells extending from their rears, chase another, rigged up as a cow, around a Spanish village. Others, playing a seedy official and his libertine wife, roam the streets flashing pornographic sketches at townspeople, blackmailing them for alms under threat of revealing naked pictures of them, as well.

The runners are known, interchangeably, as Judíos and Motilones. The first means Jews; the meaning of the second is unclear. The mêlée breaks for Mass, at the height of which the runners kiss the priest’s stole and spit gold coins from their mouths. The pursuit then resumes, capped by a gunshot in the air to signal the cow’s defeat. The day’s festivities conclude with a grand feast, the “slaughtered” cow cheerfully making table rounds to fill guests’ cups with its own “blood.”

The Fiesta de la Vaquilla, or Heifer Festival, takes place every January 20 in Fresnedillas de la Oliva, a village west of Madrid in central Spain with a population of approximately 1,500. It commemorates the martyrdom of San Sebastián, patron saint of cattle health, but its roots lie in ancient Vetton pagan rituals in which men performed feats of endurance and strength to attract mates—with Celtic, Roman-era, and Catholic motifs having worked their way in later. While most components of the festival are symbolic in nature—as in the Eucharist, the blood is, in fact, wine—others are pragmatic: the villagers were once so poor, it is said, that they were forced to sew their curtains, which were floral-patterned, into costumes, then unstitch them and re-hang them when the festival was over. The flower part stuck.

What actual Judíos have to do with any of this is unknown. Jews arrived in what is now Spain at least as early as the third century BCE. By 1492, there were about quarter of a million Spanish Jews. The cow’s escape attempt may reflect time-honored strategies of hiding cattle from the tax collector—a thankless job into which Jews were periodically pressed. Or it might jibe with local yarns about a bull incited by outsiders to break out of its pen and tear through town. In Europe, Jews were long believed to pollute wells, spread disease, and kill Christian children. Even minor misfortunes were often seen as the Jews’ fault.

In any case, a Jewish legacy is felt. Legends abound of hauntings by Jews massacred nearby. Other tales link Jews to the local seat of King Philip II, El Escorial. Though the palace came after the Inquisition, by which time Spain’s Jews had already been murdered or forced to convert, or had fled, it is thought to resemble Solomon’s temple, and prominently features statues of Philip’s regal models: Solomon the Wise himself, and the Biblical warrior-king David.

In Spain, as in Poland, Jewishness is a protean concept. Some Fresnedillans insist that Judíos are not based on real Jews at all, but rather on commoners who were smeared by aristocrats as marranos, or “Jew-pigs”—in the same manner that some European soccer fans trade the epithet “Jew” as a slur today.

Motilone is an antiquated word that translates as “the Shorn One,” a fact that has led some to link the character to the Catholic monks known for short tonsures. If so, these clergy have perhaps fallen prey to the inversion typical of pre-Lenten carnival, in which piety and social hierarchies are overturned, while sin and chaos reign. Yet Motilone has another connotation, as the name visited by the Conquistadors upon the close-cropped Bari and Yukpa peoples of South America.

The coin-spitting may reflect medieval associations of Jews with commerce; or it may allude to the influx of wealth to Spain from that colonized New World. Indeed, the invasion of Bari and Yukpa territory was spurred on by notions that lighting strikes there turned stones to gold. Or the ritual might, again, recall tax collection: both Jews and colonial subjects were perpetually, ruinously, levied. In the Vaquilla, what might further unite the two groups is the kissing of the priest: Jews and indigenous peoples share a history of coerced conversion.

Transmitted orally through countless generations, Vaquilla practices and lore tend to be shrugged off, unquestioned, as givens. Of more interest to villagers than the origins of ethnic tropes is pulling off the endlessly complex event itself. Festival talk and planning consume village life throughout the year, with highlights chuckled over, cows’ performances critiqued, costumes fashioned, menus debated, youths initiated into bachelor roles as coming-of-age rite, and funds raised for both festival and town-improvement needs. Neighboring villages host modest Vaquillas of their own, but the one in Fresnedillas is by far the most elaborate.

Advertisement

While local tourists do attend, the Vaquilla’s function seems mainly to be sustaining community cohesion through time, discord, and change. The town has long been politically divided—literally so during the Civil War, when the battlefront ran along its main street (the only time in history, townspeople proudly say, the Vaquilla was canceled). The grave of Francisco Franco, Spain’s dictator of thirty-six years, lies in the area. Some elders still, it is said, pay homage there, passing lifetime hard-line communist neighbors, to whom they barely speak, en route. Struggles remain today between right-wing former town leaders accused of embezzlement and a socialist group now in power. But the festival must go on. The Vaquilla forces opposing sides to work together.

Jobs in Spain’s small villages have always been scarce, obliging young people to move elsewhere. Fresnedillas is especially imperiled; with new highways, Madrid is only an hour away. But the Vaquilla keeps its sons and daughters coming back. One heavily tattooed young man I met had left town as a disaffected teen, but then—finding big-city life lonely—returned to vie for roles in the festival he had once scorned. Others go back and forth between the ancient and the modern worlds. The Vaquilla’s chief organizer is, by trade, an astrophysicist at a NASA Apollo station, incongruously near the crumbling stone village.

In 1994, officials from the Simon Wiesenthal Center, the Jewish institute that runs Los Angeles’s Museum of Tolerance, were flying to Spain to present an award to Queen Sofía when they noticed a feature on the Vaquilla in an inflight magazine. In uproar over what they regarded as a shocking anti-Semitic display, the Americans appealed to the European Commission to intervene. On the basis of tradition, the festival was left unchanged. The following year, however, an ABC television network program intercut images of Auschwitz and a German neo-Nazi march with footage of Fresnedillas’s Vaquilla in order to illustrate the continuity of European hatred of Jews. When the show was broadcast in Spain, it was hotly debated around the nation. In an effort to clear its name, the village brought a lawsuit. The US ambassador and the Spanish station apologized, the suit was dropped, and finally the public scrutiny of the town abated. Fresnedillans felt injured, and still do, twenty-three years later.

Beyond the Vaquilla, Jews often appear as a minor figures in other traditional Spanish settings, such as Moros y Cristianos (Moors and Christians) pageants, which celebrate the fifteenth-century Catholic rout of Muslim rule. In one of these some years ago, the Judío contingent was accompanied by a marching band playing the theme song from Exodus, Otto Preminger’s 1960 blockbuster that starred Paul Newman as a fighter for Zionist independence from the British. While this conflation of Spain’s long, proud, and tragic Jewish history with Hollywood kitsch could cause offense, as a Jew and a scholar myself, I simply find the music choice intriguing.

In recent years, curiosity about Europe’s Jewish past has led to the invention of new festivals, in Spain and beyond, striving in Disneyland-like forms to reenact it. These festivals serve very different purposes. Some, which tend to be well-informed and respectful, seek to revive lost Jewish arts, cultural, and religious traditions and educate the public about them. Others play upon philo-Semitic notions of the Jew as an exotic, soulful, and mystic figure. Still others are merely spectacles cooked up to draw national heritage grants and tourist dollars. One, in the village of Hervás, I found especially dispiriting. Its central event, a late-night play about the lead-up to the Inquisition, has gradually been edited down into a Romeo and Juliet-style Catholic-Jewish love story. By day, activity in the village revolves around a “Jewish” market selling cheap trinkets with no relation to the festival’s theme and pork-based snacks. Fresnedillas’s genuinely folkloric Vaquilla lies in a completely different category.

As a cultural fixture of probably more than two millennia, the Vaquilla is a rare find—worth preserving in as much of its totality as possible. But would it hurt to drop “Judíos” as the name of one of the bachelor groups? Hardly. As living history—not untouched, but embraced by time—what the Vaquilla shows is that traditions at once endure and evolve.

Girls now participate in children’s Vaquilla events that were once reserved for boys. Women have not yet joined the bachelor run, but are invited to do so. And with an influx of immigrants from Ecuador, Morocco, and twenty-one other countries that has made Fresnedillas one of the most diverse towns in the country, the Vaquilla has gradually grown multicultural. Among those supporting it are the village’s Spanish Jews. In meaning so much that no one can quite define them, “Judíos” and “Motilones” come to mean not much at all.

Advertisement