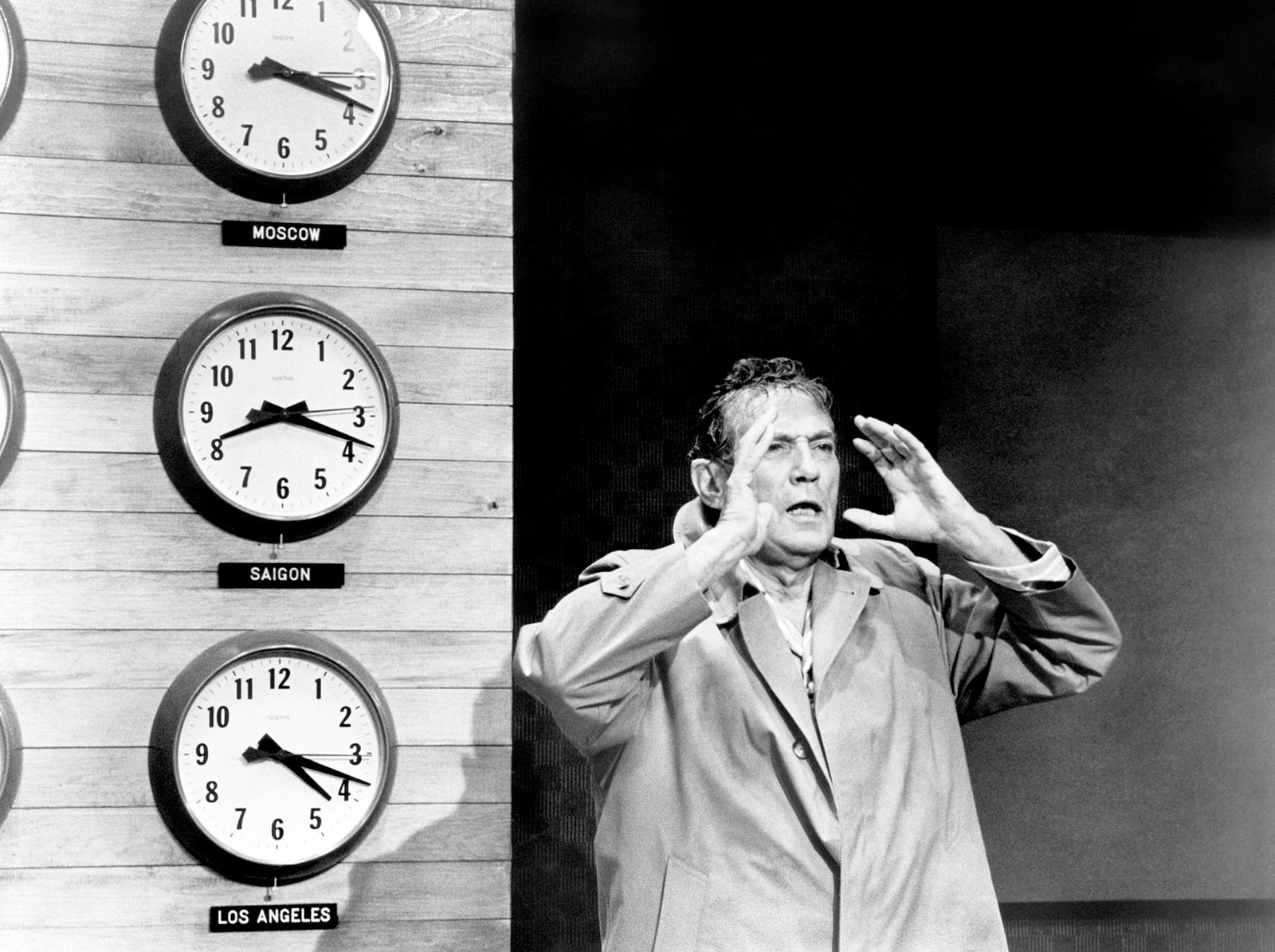

Network, one of the big movie hits of 1976, now seems prophetic in both senses of the word. The Old Testament prophet is typically less interested in seeing into the future than in denouncing the iniquities already present in the world. Howard Beale, the deranged TV news anchor created by Paddy Chayefsky, is a comic, deluded, but nonetheless captivating descendant of Jeremiah or Ezekiel.

But the film has also come to seem prophetic in the more colloquial sense. Even before the rise of Donald Trump, Aaron Sorkin, the creator of The West Wing, claimed that “no predictor of the future—not even Orwell—has ever been as right as Chayefsky was when he wrote Network.” The film deals with the rise of infotainment, the decline of hard news, the birth of a culture in which we are assailed by an unending storm of images, the collapse of objective reality, and the emergence of a global market. The tycoon Jensen instructs Beale:

We no longer live in a world of nations and ideologies, Mr. Beale. The world is a collage of corporations, inexorably determined by the immutable by-laws of business.

This may seem obvious now. It was not in 1976, when China was still Maoist and the Soviet Union seemed certain to endure. As if that was not prescient enough, Network also appears to foreshadow in the United States a politics of pure rage. It is not just that Beale’s televised rant echoes through into the present, but that the echoes seem to grow louder all the time:

I don’t want you to protest. I don’t want you to riot. I don’t want you to write your congressmen. Because I wouldn’t know what to tell you to write…. All I know is first you’ve got to get mad. You’ve got to say, “I’m a human being, goddammit. My life has value.” So I want you to get up now. I want you to get out of your chairs and go to the window. Right now. I want you to go to the window, open it, and stick your head out and yell. I want you to yell, “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this any more!”

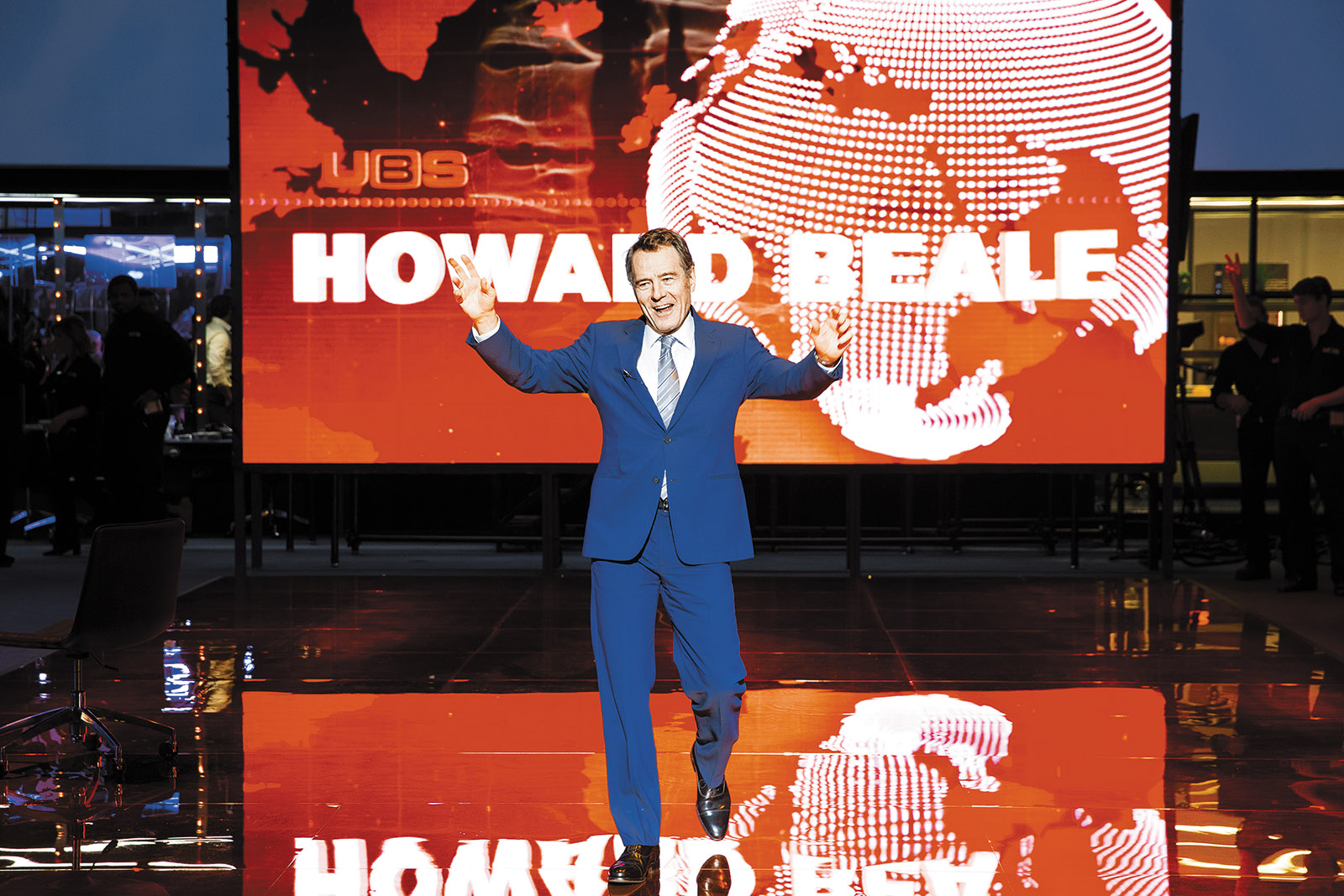

It is not at all surprising that Ivo van Hove’s often stunning staging of Lee Hall’s adaptation of Network, with the mesmerizing Bryan Cranston in the role of Beale—for which Peter Finch won a posthumous Oscar in 1977—is the great success of the current London theater season. When Michelle Dockery, as the cynical and amoral program executive Diana, argues that the articulation of rage is better box office than “the business of morality,” the lines feel, after the era of Trump, like a recognition scene in a Greek tragedy. How many networks, after all, told themselves that Trump the candidate was great for ratings?

Adapting a movie for the stage is often a futile exercise, but a theatrical version of Network makes sense. On the one hand, the film is highly unusual for its verbosity and long set-piece monologues. Its director, Sidney Lumet, called Chayefsky “the Jewish Shaw,” and Network does indeed hark back to the Irish playwright’s mix of verbal arias, madcap absurdity, and moral outrage. On the other hand, the film also plays with the dizzying nature of electronic imagery, switching deftly between live action and scenes glimpsed on multiple TV screens and studio monitors. Van Hove’s production makes the most of both of these possibilities, relishing Cranston’s old-fashioned rhetorical power while also creating a vertiginous whirl of perceptions in which the live action on stage is being filmed by black-clad technicians whose presence, like the kuroko of kabuki theater, we both see and ignore. The filmed images are in turn broadcast on huge screens, but just slightly out of synch with the action, so that we cannot escape from visual and cognitive dissonance.

The sense of disorientation is heightened by the way van Hove and the set designer Jan Versweyveld fracture the theatrical space of the Lyttelton Theatre. Never mind the fourth wall, the stage has walls within walls. Stage right is dominated by a transparent glass box that is the TV control room. Sometimes we can hear what is being said within it, at other times the action inside unfolds as a dumb show of gesticulations. Stage left is a working restaurant, where patrons who have paid for the privilege eat and drink. Some of the action happens here, such as the crucial early scene where Beale, about to be fired because his ratings are disappearing below the horizon, half-jokes with his boss and old friend Max Schumacher (William Holden in the movie, Douglas Henshall onstage) about killing himself on air. The device jumbles reality and representation, audience and actors. Between these two spaces, there is the TV studio. Behind them is Beale’s dressing room, where the mirrors create further reflections and refractions. And even these spaces are subverted when Dockery and Henshall move outside the theater altogether and the camera follows them, relaying their movements and dialogue back to us inside.

Advertisement

As an experience, this is at once woozy and spellbinding. And yet, onstage as onscreen, Network raises a question it can never quite answer: What is all the rage at? What are we supposed to be mad as hell about? Chayefsky himself, as he drafted the screenplay, wrote in capitals across a page from his notebook, “THE SHOW LACKS A POINT OF VIEW.” The dazzling diversity of perspectives in the stage version gives us many simultaneous points of view, but does this merely mask the absence that so worried Chayefsky? As Dave Itzkoff reveals in his vivid and illuminating book on the making of the movie, Mad as Hell: The Making of Network and the Fateful Vision of the Angriest Man in Movies (2014), Chayefsky’s critical self-analysis continued:

I guess what bothers me is that the picture seems to have no ultimate statement beyond the idea that a network would kill for ratings…. We are making some kind of statement about American society and its lack of clarity is what’s bothering me—Even more, I’m not taking a stand—I’m not for anything or anyone—If we give Howard [Beale] a speech at the end of the show, what would he say?

Chayefsky never came up with an answer—Beale is murdered on live TV and gets no final speech.

At this distance, however, it is easier to see the sources of the rage that overflows in the original Network. There are three specific anxieties behind it. The first is the rise of feminism and the appearance of the high-powered professional woman. Diana, played in the movie by Faye Dunaway, is the driver of the plot. She is the obsessively ratings-driven head of programming at the network who recognizes that Beale’s rantings could be turned into a hit show. But she is also the femme fatale who lures the middle-aged Max away from his wife.

Chayefsky does not know how to combine Diana the career woman with Diana the sex siren. In his script, he introduces her as “thirty-four, tall, willowy and with the best ass ever seen on a Vice President in Charge of Programming.” He has her tell her staff “I don’t want to play butch boss with you people,” suggesting of course that butch boss is exactly what she is. She is thus a kind of chimera—a bossy man in a sexy woman’s body. Indeed, sexually she is all male. She tells Max before their first date:

I can’t tell you how many men have told me what a lousy lay I am. I apparently have a masculine temperament. I arouse quickly, consummate prematurely and can’t wait to get my clothes back on and get out of that bedroom.

The second source of anger is the rise of uppity and dangerous blacks. At the end of the film, the camera focuses on a big African-American man in the audience of Beale’s live show. He stands up and shoots Beale with a submachine gun. There is also a white shooter on the other side of the studio, but it is the image of the black man that is repeated on the TV screen shots that brings the movie to a close. This is the culmination of the subplot of Network that has Diana creating a weekly show around an ultra-leftist terrorist group, the Ecumenical Liberation Army.

The leader of the ELA, the ludicrous Great Ahmed Khan, is “a large powerful black man.” Arthur Burghardt, who plays Ahmed in the movie, was a real political activist who had been jailed for draft evasion. He told Itzkoff that when he read the part he immediately recognized it as a caricature of the black power leader as “a tyrant, a punk, a criminal,” but “I decided I’d play the archetype to the hilt.” Although it is scarcely noticeable in the movie, Chayefsky specifies that Khan is to be seen wearing “the crescent moon of the Midianites” around his neck, linking him in the writer’s mind to the biblical tribe driven out of Israel by the Jews and also to Islam, for which the crescent moon is a symbol.

This points to Chayefsky’s third pool of apprehension. He lived in dread of a second Holocaust. In an interview with Women’s Wear Daily in 1971, he expressed the belief that all Jews around the world were in danger of imminent genocide. “Six million went up with a snap of the finger last time, and there is little reason to assume anybody’s going to protect the other 12 million still extant,” he said, and added that the risk was especially great in the United States: “There’s a lot of anti-Semitism in America, real gutter Munich stuff. You hear it in the New Left: ‘Kill the kosher pigs.’” Network was written after the oil crisis of 1973, when the Arab-led Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries placed an embargo on exports to states that had supported Israel. One of the main objects of Beale’s ranting is the threat of a Saudi takeover of the Communications Corporation of America (CCA), the network’s owner:

Advertisement

Well, I’ll tell you who they’re buying CCA for. They’re buying it for the Saudi-Arabian Investment Corporation! They’re buying it for the Arabs!… We know the Arabs control more than sixteen billion dollars in this country!

This apocalyptic fear of annihilation is interwoven with a subtler sense of loss: the collapse of the Jewish prophetic tradition. Beale is a showbiz Jeremiah, a loopy Moses, and a deranged Messiah. The send-up of the idea of prophecy is at the core of the film’s humor but also of its bleak vision of the complete loss of cultural meaning.

When Diana is later looking to replace Beale because his ratings are falling, we see a screen test by a phony long-bearded figure standing on a mountaintop dressed in the kind of garb that Moses tends to wear in early biblical epics. The directions in Chayefsky’s screenplay are dismally dismissive of what the Jewish prophetic tradition has come to: “The Mosaic figure on the console rants until otherwise indicated.”

These specifically Jewish anxieties are important because they suggest that the audience’s wildly enthusiastic reaction to Beale’s “mad as hell” rant is supposed to make us deeply uncomfortable. In Chayefsky’s original narrative treatment for the screenplay, the import of the famous scene in which we see viewers all over America obey Beale’s command to go their windows and shout out their anger is unambiguously ominous:

Thin voices penetrated the dank rumble of the city, shouting: “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it any more!” Then, suddenly it began to gather, the edges of sounds and voices, until it all surged out in an indistinguishable roar of rage like the thunder of a Nuremberg rally.

In the finished screenplay, Chayefsky’s fears break out into melodramatic capitals:

A terrifying THUNDERCLAP, followed by a FULGURATION of LIGHTNING, punctuates the gathering CHORUS coming from the huddled, black border of the city’s SCREAMING people, an indistinguishable tidal roar of human RAGE, as formidable as the THUNDER RUMBLING above. It sounds like the Nuremberg rally.

The underlying problem for Lee Hall’s stage adaptation is that it has to suppress these neuroses. They are too awkward for our times. The misogynistic image of Diana as the butch boss and sexual chimera is greatly softened in Michelle Dockery’s portrayal. The scene in the movie where Dunaway talks incessantly about TV programming as she mounts Max and climaxes while still discussing time slots and ratings is shifted from the bedroom to the onstage restaurant. It becomes more surreal, more comic, less vicious. Diana is still screwed up but there is a much less obvious suggestion that her “masculine” sexuality and amoral cynicism are the inevitable results of a woman’s pursuit of professional ambition.

Even more starkly, the stage version is scrubbed clean of racial anxiety. In Chayefsky’s screenplay, “busing trouble in Boston” is one of the news stories running on the TV screens as the story begins. In Hall’s version, it is gone. In the original, Beale’s rants specifically imagine America as a white society: “This is a nation of two hundred–odd million, transistorized, deodorized, whiter-than-white, steel-belted bodies.” Hall gets rid of “whiter-than-white”: “This is a nation of two hundred–odd million, transistorized, deodorized, dehumanized beings.”

The theater show itself is not whiter than white—black actors play one of the main network executives, a reporter, and a technician. More importantly, the black terrorists are expunged. Beale is not shot by a black man.

As for the Jewish strain of Chayefsky’s screenplay, it too is played down. Other than Beale’s paranoia about an Arab takeover of the US, it is admittedly more implicit in the film than explicit. But there are two specific moments that draw attention to it. One is when the head of the news division, Edward Ruddy, dies. Chayefsky specifies that his funeral takes place in Temple Emanuel on 65th Street in New York and the film establishes this location in a clear exterior shot.

The other, more subtly, is near the start of the film when Beale and Max, in their cups, are improving on the possibilities of a weekly show in which people are killed on air: “We could make a series out of it…. Every Sunday night, bring your knitting and watch somebody get guillotined, hung, electrocuted, gassed.” Hall distances the historical analogies and drops the implicit reference to the Nazi gas chambers: “We could make a series out of it…. Every Sunday night, settle down and watch someone get hung drawn and quartered.”

These changes are all in good taste, yet they leave a hole where Chayefsky’s phobias and fixations should be. Without the paranoia about women in masculine roles, the threat of a black uprising, and an Arab-funded anti-Semitic takeover of America, the stage version of Network is more decent and less rancid than the film. It is also somewhat defanged. In an era when American politics have been dominated by the mobilization of anger at very specific groups—Mexicans, Muslims, “elites,” the Black Lives Matter campaign—this version of Network offers a rage that is not really at anyone at all. And this makes for a peculiar anomaly—it feels prescient sure enough but also too benign for the present moment. As an articulator of American rage, Howard Beale is just so much nicer and more humane than Donald Trump. The roar of the Nuremberg rally that Chayefsky heard in the audience’s echoing of his “mad as hell” battle cry is even more muted than it was in the movie.

In some respects, this is an advantage for Bryan Cranston. Peter Finch’s original Beale is tremendous because he does not indulge in mere mad acting—he is calm, controlled, at times almost dissociated from his own harangues. Cranston takes up where Finch left off. The real-time countdowns to his live TV broadcasts allow him to emphasize just how cool Beale is, as he talks or dresses right up to the moment the camera’s red light goes on. He is no maniac—or rather his mania is indistinguishable from his normality. This is, after all, what makes Cranston such a great actor. Most good actors can move convincingly from one state to another; Cranston acts both simultaneously. His justly celebrated Walter White in Breaking Bad was not a mild-mannered chemistry teacher turned crystal meth maker and killer—he was always completely both men, always nice and loving and terrifying and cruel.

The same ability to integrate opposites was apparent in Cranston’s last stage role, as Lyndon Johnson in Robert Schenkkan’s All the Way on Broadway in 2014. His LBJ was not by turns monstrous and noble, but thoroughly demonstrated each of these qualities simultaneously. The lovely paradox of his Howard Beale is that even as van Hove is swirling us around a disintegrating world, he is the one person who remains oddly integrated, seamlessly containing madness and self-control, wildness and restraint, delusion and calculation. There is no split in his personality: the rhetorical rage is a smooth continuation of the quiet despair that Cranston so movingly embodies.

So, to some degree, the suppression of Chayefsky’s original anxieties works because it feeds into a superb performance. By cutting away most of the terrorist subplot, Hall allows for a clearer focus on Beale. While the movie begins with a voiceover telling us, “This story is about Howard Beale,” the stage version changes it to “This is the story of Howard Beale”—a subtle but telling shift. Beale’s part is enhanced with more lines: an important journalistic war story that Max tells (and repeats) about an incident in his early career is taken from him by Hall and given instead to Beale, so that it can act as a comic foreshadowing of his tragic death wish. All of this makes it easier for Cranston to be richly sympathetic, to turn the mad prophet into a melancholy everyman who has reached the end of his tether. He may be mad as hell, but hell is his own life; what he cannot take anymore is being himself.

Cranston makes this existential desolation moving and funny and paradoxically vibrant. What even he cannot quite do, though, is to give it a political cutting edge. Hall’s version of the story is no more certain about the ultimate political point than Chayefsky’s was. In some ways, it is less so. Chayefsky’s at least had a grounding in an economic depression in the US, and Beale acknowledges this even while he is urging his audience to express its rage: “First, you’ve got to get mad. When you’re mad enough we’ll figure out what to do about the depression.” It is typical of Hall’s interventions in the script that this becomes less specific: “First you’ve got to get mad. When you’re mad enough we’ll figure out what to do.”

Hall, to his credit, does try to figure out what Chayefsky could not: how to give Beale a concluding and conclusive speech. The ending encapsulates both the strengths and the problems of this version of Network. Beale’s assassination is superbly staged, and in a brilliant coup de théâtre, Cranston magically appears outside of the double image of his own dead body on the stage and the video screen. He sits on the side of the stage, using his gift for intimacy to draw the audience toward him in sorrow and sympathy, and delivers a last monologue:

And so Howard Beale became the only TV personality who died because of bad ratings. But here is the truth: the “absolute truth,” paradoxical as it might appear, the thing we must be most afraid of is the destructive power of absolute beliefs—that we can know anything conclusively, absolutely—whether we are compelled to it by anger, fear, righteousness, injustice, indignation; as soon as we have ossified that truth, as soon as we start believing in that Absolute—we stop believing in human beings, as mad and tragic as they are. The only total commitment any of us can have is to other people—in all their complexity, in their otherness, their intractable reality…this is truly what I believe: it is not beliefs that matter it is human beings. This is Howard Beale signing off for the very last time.

This is sweet and decent and Cranston makes it deeply affecting. But it is surely too sweet and too decent. Beale should be terrifying: if his story really means anything to our times, it is not about how we must love one another but about how rage can be so dangerously satisfying and so treacherously entertaining.

After this speech, van Hove has the video screens show the succession of presidential swearings-in since the original film was released, from Jimmy Carter in 1977 to Donald Trump in 2017. On the evening I was there, the audience spontaneously greeted the sight of Trump with cries of “We’re mad as hell and we’re not going to take it anymore!” One could not help but feel that some of the ambiguity of this cry was being forgotten, some essential irony lost.

This Issue

March 8, 2018

Hell of a Fiesta

Ghost Whisperers

Roth Agonistes