In 2001, when Assia Boundaoui was sixteen years old, she woke up in the middle of the night, roused by lights shining outside her bedroom window. She looked out to find two men aloft fiddling with the wiring of the recently installed street lamps.

She ran to her mother’s room, afraid, telling her they should call the police. Her widowed mother tried to calm her down. “It’s not a big deal,” she said. “It’s probably just the FBI. Go back to sleep.”

By that year, the FBI had become such a ubiquitous presence in the small town of Bridgeview, Illinois—home to some 200 Muslim Arab-American families—that the residents attributed many extraordinary and unexplained occurrences to what the community suspected was the government’s surveillance of their every move. There were the unknown cars that sat for hours outside their houses; men who didn’t appear to be in need going through their trash cans; and odd clicking sounds and static on the line when residents spoke on the phone.

Boundaoui herself was eleven the first time she can recall the appearance of FBI agents on her family’s doorstep, asking to interview her father. A professor of math at Chicago State University, he was also the vice president of the local mosque. (Both her parents were from Algeria and were granted asylum in the United States when it was no longer safe for them to return home. Her father died in 1999.) None of the people who were visited in those years knew exactly why they had come under scrutiny—whether they themselves, or someone else, or the entire community itself was the target, or whether any of this even added up to formal surveillance. Fear, shame, and isolation began to fester in Boundaoui’s community, which in turn fed a rampant paranoia. Their watchers—if they were being watched—became ever-present, whether they were actually there or not.

What does it mean to raise a family or to grow up under constant surveillance? How does it affect a person’s quality of life? What does it do to the potential of an individual, a family, a neighborhood, and a society?

Boundaoui, now a journalist, examines the effect of living under constant surveillance in her first documentary, The Feeling of Being Watched, which premiers today at the Tribeca Film Festival. (A few months ago, I saw an early cut of the film and was asked to give a critique of any loose legal or narrative threads.) The film weaves the personal and the political, as Boundaoui investigates whether the community she grew up in was indeed under official government surveillance for over a decade.

The film doesn’t offer a definitive answer. In it, Boundaoui attempts to uncover the truth by working diligently to convince reluctant community members to speak. But many refuse to answer Boundaoui’s knocks on their doors; they offer her baked goods but no testimony; some even insinuate that she should be more deferential to the FBI.

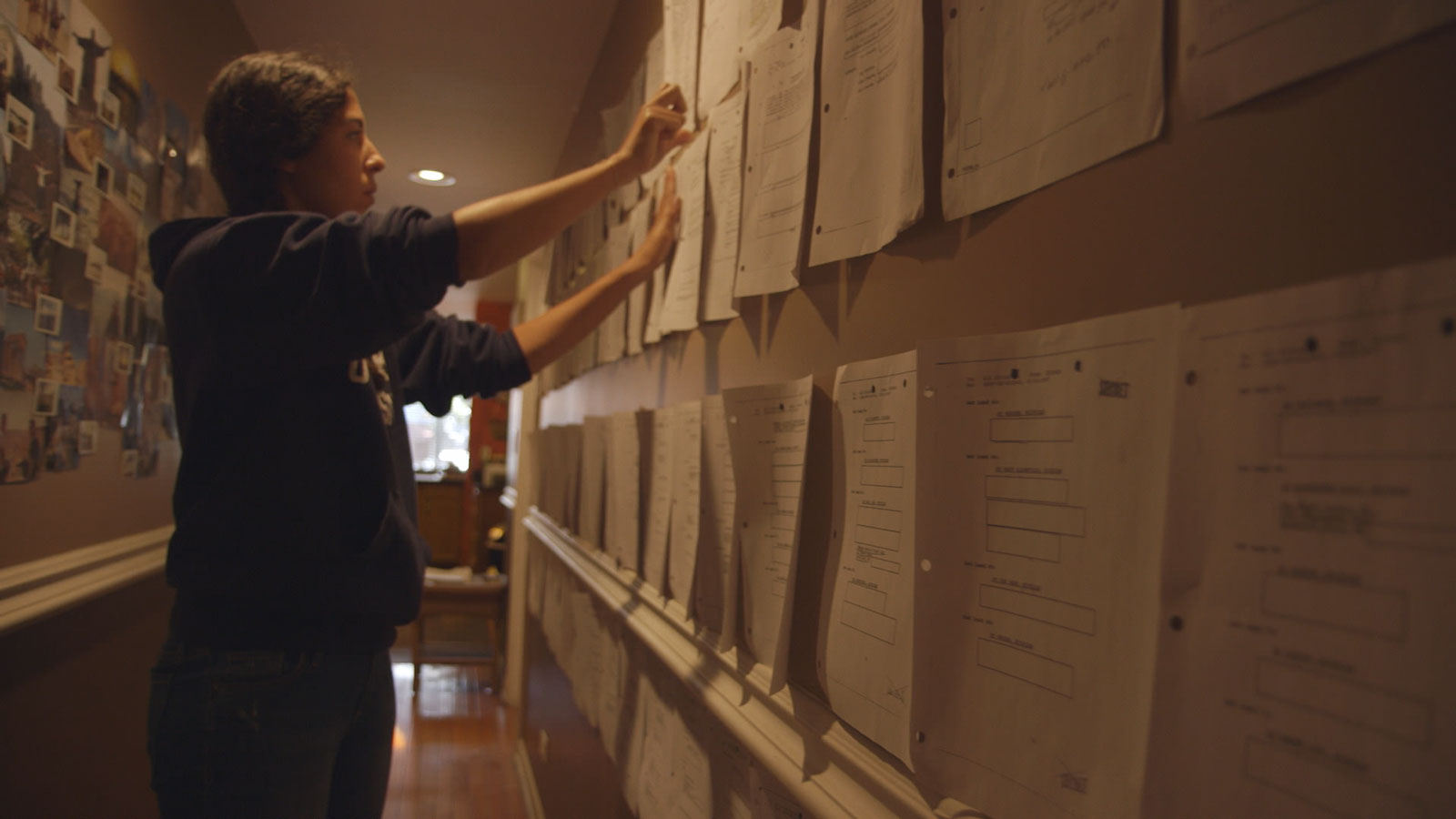

Met with this silence, Boundaoui combs through press clippings and declassified documents. With clues she finds there, she files several FOIA requests with the FBI and the Department of Justice, all of which are denied. Undaunted, she sues the FBI and the DOJ to compel them to release the relevant documents, which the government had conceded numbered over 30,000 pages, as a way to object to the burden of what she was requesting. The court rules in her favor. (To date, she has received nearly 5,000 pages of documents and more arrive each month as per court order.)

Boundaoui pieces together the truth that, indeed, her small neighborhood was the target of a secret FBI counterterrorism probe codenamed Operation Vulgar Betrayal, led by a particularly zealous FBI agent. But she still doesn’t know many of the specifics, including why the probe was opened and whether it ever ended. But while she connects Vulgar Betrayal to a long history of FBI surveillance of communities of color, the aim of the film is not a comprehensive look at this history or even that of US surveillance of Arab and Muslim Americans, which predates September 11 by decades. It could hardly be Boundaoui’s responsibility to address, in 86 minutes, all the lacunae in that story.

Instead, in Boundaoui’s film, she offers up herself and her charismatic siblings and mother as a way to draw attention to what was done to people who are not the menacing, terrorist sympathizers of the public imagination—a family that appears, in fact, utterly normal. In addition to investigating Vulgar Betrayal, Boundaoui burdens herself with trying to correct how many Americans perceive American Muslims: breezy scenes of her and her friends roller-skating, eating cupcakes, and taking selfies at joyous Eid celebrations and picnics seem consciously included, an indictment more of how unfairly these communities have generally been portrayed.

Advertisement

Critics might, however, dismiss this as a glossed over portrait. Vulgar Betrayal suspected that the Bridgeview mosque’s charitable donations benefited Hamas. But none of those suspicions held up in court, and the operation did not yield a single terrorism conviction. The scarlet stain of these accusations nonetheless disrupted many lives, and Boundaoui mentions families that just left their homes in the US (often after decades here) and started over again in other countries. But she chooses not to go too deeply into the details of the allegations or the bigger picture (other jurisdictions in the US have also targeted Arab and Muslim American communities over similar suspicions of charitable giving), concluding that obtaining convictions may not have been the real point of Vulgar Betrayal.

She likens her community’s experience to that of inmates of a panoptican prison, designed so that inmates can be observed by a single watch-station, though not all at the same time. Because inmates can’t tell who is being watched when, they are nonetheless motivated to regulate their own behavior. Boundaoui concludes that the feeling of being watched, the paranoia, might not just be an effect, but rather the purpose, of the surveillance. While Boundaoui’s quest to understand Vulgar Betrayal more fully will require time, it’s not her only objective. If surveillance is going to be a regular part of American life, as it already is, then she is determined to name it. In the spirit of inverse surveillance, Boundaoui wants to “watch the watchers.”

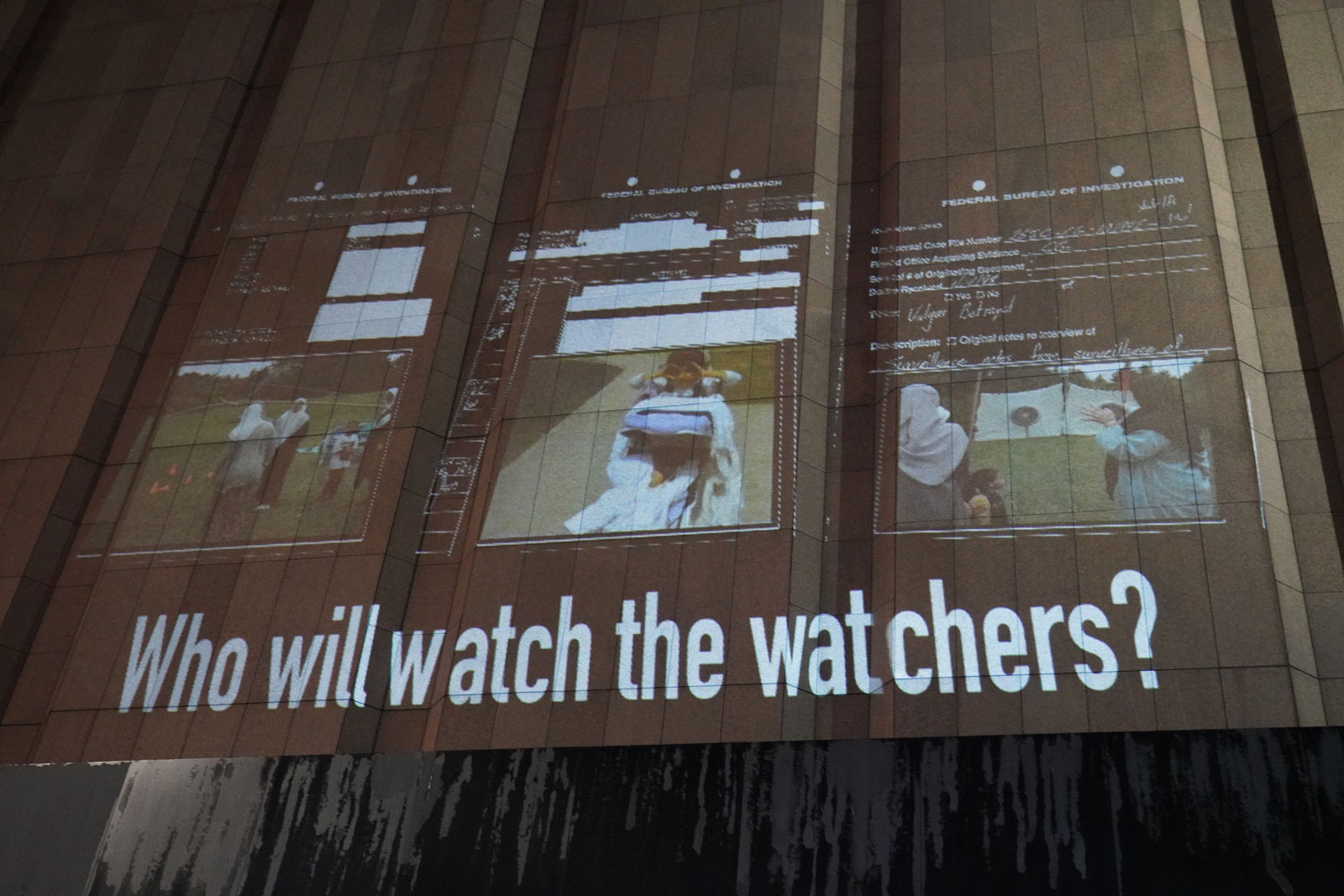

To that end, Wednesday night in Manhattan, Boundaoui collaborated with the projection artist Robin Bell, in partnership with the MIT Open Doc Lab, to guerrilla-project a work of video art that Boundaoui created as an offshoot of the film. (Bell is known for his projections on Trump-owned properties.) In the piece, meant to be projected onto the side of a building, are images of FBI declassified documents from Vulgar Betrayal. Between lines of scribbled words are large expanses of redacted space. Rather than allow viewers to imagine what or who might be hidden behind those squares, which the government implies are nefarious (otherwise, why would they be under surveillance?), she fills them with images from her family’s mundane home videos.

Boundaoui and Bell chose the brutalist AT&T Long Lines Building as the site for their projection, an informed choice given that the NSA conducts secret surveillance from inside the very same building, designed to withstand nuclear fallout. (It was outed as “Titanpointe” by the Snowden leaks.) By projecting their video art onto it, Boundaoui and Bell aimed to deny the government its demand for near absolute secrecy in the name of national security.

Shortly after 9 PM, in three side-by-side panels, 1.5-story-tall hijabi-clad women practiced archery, jumped rope, and rode horseback on a family camping trip against the smooth windowless concrete backdrop of the AT&T building. Kindergarten children graduated in full cap and gowns. Happy crowds brought balloons to an event at the mosque. Underneath were projected the words “Who will watch the watchers?” (in Latin as well as English) and “#beingwatched.” At that hour, the street was largely deserted. A homeless person slept at the foot of a nearby building with a plaque honoring Vincent D. McDonnell’s “unselfish and tireless efforts on behalf of the NYC Detectives’ Endowment Assn. Inc.” (Two weeks ago, the NYPD settled a third lawsuit with Muslim Americans who had sued it over its surveillance of their communities.)

But for those passers-by who stopped to watch, Boundaoui was on site to explain her installation. No police or security approached, as often happens with Bell’s projections. The projection, which was livestreamed, could have gone on; in the end, they allowed the minute-plus video to loop for nearly half an hour.

The only hiccup occurred earlier in the evening, at a nearby Dunkin Donuts. Boundaoui, Bell, and the rest of the projection team were meant to meet there for last-minute tweaks. But the staff started to shut up shop earlier than expected. Unsure where else to go, Bell leaned across the counter and dropped his voice: “I’ll give you forty bucks if you let us stay.”

The cashier responded, “Sorry, I can’t. My boss… .” Trailing off, he gestured behind him to the black hemisphere of a surveillance camera looking down at them.

Advertisement

The Feeling of Being Watched is showing at the Tribeca Film Festival April 21 through 29.