In recent decades, a tale unfolding within the larger story of contemporary art has been our gradually learning more about, and our trying to place, outsider artists. Problems begin at once, with the label. It is a description that many remain ambivalent about, and often believe should be put in quotation marks, to indicate its tentativeness. The situation somewhat echoes the moment, beginning in the 1920s and 1930s, when folk art was first being taken out of attics and looked at anew, and commentators were not sure whether that term—or the labels “self-taught,” “naive,” or “primitive,” among others—was the appropriate one or would merely suffice. “Self-taught,” though imprecise in its way—it has been said, for example, that most of the significant painters of the nineteenth century were essentially self-trained—has remained interchangeable with “folk art” for many commentators. It is sometimes used interchangeably with “outsider,” too. It strikes far less the note of a judgment from above.

Yet “outsider” catches better the quality often evident in the work of such creators of being a surprising, or possibly strange, one-of-a-kind accomplishment. Put roughly, an outsider artist is a figure who makes a body of work while operating in relative isolation, unaware of, or indifferent to, developments in the work of professional artists—though this isn’t always the case and it doesn’t mean that such a person is unaware of being an artist. Nor should it suggest that an outsider artist is a sporadic creator. Many are mightily prolific.

An outsider artist might be someone who resolutely, and perhaps eccentrically, wants to live and work only on her or his terms. An outsider artist might be someone who has been institutionalized, or who suffers some physical impairment, which keeps the person at a remove from others. But an outsider artist, as the term has evolved, might as easily be someone whose daily experience—as, say, a black person in the South—has kept that person from having any real contact with the larger culture beyond his or her immediate community.

Outsider art is largely a phenomenon of the last century (as the richest examples of folk art date to the first half of the nineteenth century), and at this point there are numbers of such creators whose accomplishments we look at with love and admiration. Simply to give a sense of the range of such figures I would mention Bill Traylor, who was born a slave and was discovered in 1939 working out of a booth on a street in Montgomery, Alabama. His gift was for finding the most precise and elegant way to place his silhouette-flat human and animal figures on otherwise empty pages. Twisting, running, growling, and gesticulating, his characters, although not part of some larger atmosphere, seem nevertheless to conjure a vast rural universe. The Czech Miroslav Tichý, on the other hand, who made some of his cameras out of wood, tape, and cardboard, gave photography, in shots made mostly in the 1960s and 1970s of the women of his town—going swimming, waiting for a bus, walking away—a new dimension. He showed how offhand and blurry a photograph can be and still be evocative.

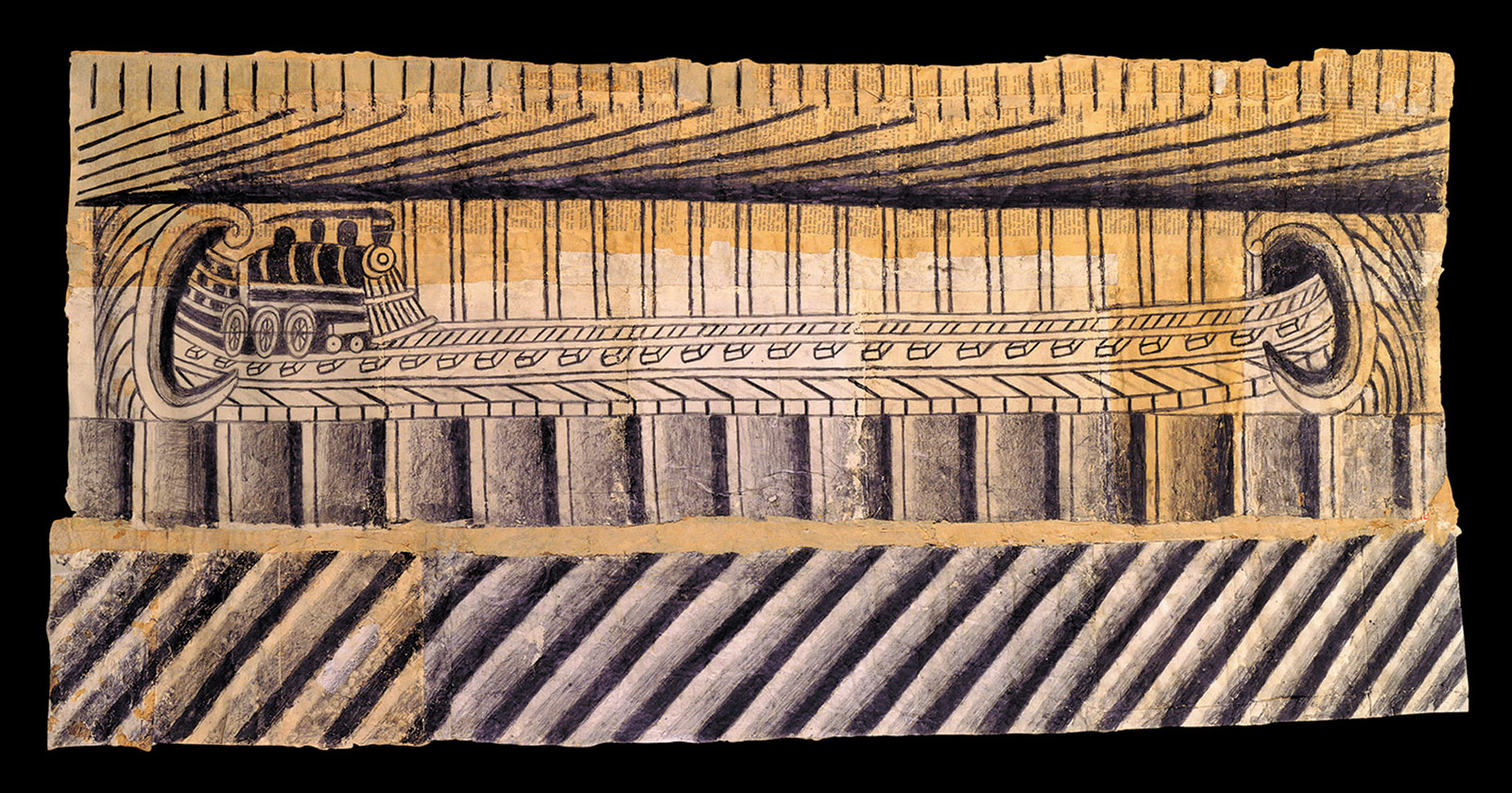

In images that, like Tichý’s, present a largely gray-colored world, James Castle, who lived with his family in rural Idaho (and died in 1977), and made his pictures using primarily soot and saliva, fashioned interior and exterior scenes that could be lessons in the balancing of tones and shapes. In his boxy little pictures and his (even better) flat sculptures of shirts, fashioned out of string and random paper boards, the whole world seems as if made over in some raw, scratchy, yet softly modulated way. And the Mexican-American Martín Ramírez, all of whose work was done in California mental institutions in the last thirty years of his life (he died in 1963 at sixty-eight), gives us images that, composed of black parallel lines set against subtly sandy backgrounds, suggest an epical flow of mountains, tunnels, windows, and trains. We see forces forever opening out and closing in.

Studies of the art of the mentally ill date from the 1920s, but the term “outsider art,” which broadened the topic to include work by people immersed solely in their own worlds, arrived in 1972 with the publication of the English writer Roger Cardinal’s study Outsider Art. Since then, and especially in the last two decades, an ever-rising number of museum exhibitions and academic studies have added to our awareness of the terrain. There are commercial galleries and collectors concerned exclusively with outsider art, and, more significantly, we continue to encounter for the first time work by persons who seem to fit the label. Within the last year alone there were exhibitions in New York of the pictures of Eugen Gabritschevsky, a Russian biologist who suffered a severe breakdown in the late 1920s and proceeded to produce a large body of beautiful fantastical drawings in a psychiatric hospital, and Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934), a Nobel Prize–winning Spanish neuroanatomist whose drawings of slices of the brain, seen with a microscope, form images, at once abstract and naturalistic, not quite like anything most of us have seen before.

Advertisement

By a good coincidence, two exhibitions running at the same time make clear that the appreciation and understanding of outsiderdom remain fluid and exploratory. At the National Gallery of Art, “Outliers and American Vanguard Art” gives us not only a new label—“outliers” instead of “outsiders”—but, more ambitiously, and with a certain confusion, a look at how trained, and progressive, artists have responded to outsider art. At the American Folk Art Museum, the exhibition “Vestiges and Verse: Notes from the Newfangled Epic” takes up the subject of outsider artists who were either writers of a sort as well as visual artists or who conceived their pictures as illustrations to ongoing stories.

The National Gallery’s show is the brainchild of Lynne Cooke, who tells us that she became involved with the subject after seeing a Ramírez retrospective in 2007 and a Castle exhibition two years later. She believes in the importance of figures who make art that might challenge, or simply go off in its own direction from, the ongoing current of professional or mainstream art. But she wants to recast how we see these challenging figures. In effect, she wants to modernize them. She wants us to think of them less as aberrant persons.

Cooke believes, too, that there is a particularly American character to the story of untrained artists and their interaction with professional, vanguard artists. She says that while self-taught artists in Europe or Latin America are often figures who have been institutionalized, and whose art stems from their illnesses (she does not mention any names), in the United States such artists generally “appear, against the odds, from ranks disadvantaged by class, race, ethnicity, and gender.” Pursuing the thought that European and American responses have been different, Cooke notes that “naive expression” has not had much of a part in “modernist European histories”—whereas work by self-taught artists has been welcomed by avant-garde artists in the States and often used in their own efforts. She has in mind, to take one instance, the way Elie Nadelman’s delicately rounded and colored wood sculptures of figures in society (one is in the show) appear beholden to folk-art wood toys and whirligigs.

It is Cooke who has renamed outsider artists “outliers.” It is an astute choice and one that may stick. Where “outsider” has a them-versus-us quality and can suggest two separate realms of creativity, “outlier” seems to convey that no matter what their training or lack of it, people who make art are all involved in the same endeavor. Besides, the word “outlier” is, Cooke writes, “unmistakably of our era; it situates this project in the present.” It bestows an unexpected hipness on these figures. An outlier, she says a bit romantically, is “a mobile individual who has gained recognition by means at variance with expected channels and protocols.” What her words mean, it would seem, is less that outliers are pirates on the high seas than artists who are aware of their creativity and desirous of having it known. They are not oblivious to the world.

Cooke’s distinctions are fresh and worth mulling over. But her exhibition, which ranges in time from two (lovely) pictures by folk painters of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to artworks of the present—and jumps from work by outliers to works by modern and progressive artists who are presumably thinking about outliers—is slippery, diffuse, and not always convincing. Even if you are an insider you may often not be sure of the ground you stand on.

It is vaguely peculiar, for instance, that one of the early rooms of the show gives us primarily pictures by folk or untrained artists that either were shown at the Museum of Modern Art in the 1930s and early 1940s or are of a piece with those works. The point is presumably to indicate how welcoming the professional American art world was in an earlier era to nonestablished figures. Some of the paintings in this section, notably by Horace Pippin and Joseph Pickett, are remarkable, and Edward Hicks’s 1848 picture of James Cornell’s farm is a masterpiece. Grand in size and quirky in its empty-in-the-center composition, the canvas is one of a small handful of works that imaginatively rethink the subject of farms and farming, which was at the core of American life before the Civil War.

Advertisement

But many of the pictures, whether by French or American artists, and showing, respectively, public urban life or southern rural life, have little more going for them than their naiveté. Looking at them, one wonders why livelier examples by American self-taught artists were not chosen. I am thinking of the speedily drawn and brilliantly colored views of Thomas Chambers, say, or, from later in the nineteenth century, the unnervingly finicky realist pictures of home life by Edwin Romanzo Elmer, whose turf was Massachusetts’s Pioneer Valley.

There are, though, winning works on hand as one continues through the exhibition. It is a treat to come upon a unit of sculptures by the stone carver William Edmondson, whose angels, horses, and other figures, dating from the 1930s and 1940s, are at once extremely chubby and tensely at the ready. The little-known painter William H. Johnson, a trained artist who took on a primitive style emphasizing his African-American heritage, makes a terrific impression with his Swing Low, Sweet Chariot (circa 1944), in which the descending chorus of angels are like schoolgirls of the era, each in ankle socks and Mary Janes.

But as we check off the works by Ramírez, or Castle, or the professional Chicago-based painters who were looking at the art of outsiders, or the religious carvings and assemblages of Elijah Pierce or Howard Finster, or the quilts made by, among others, quilters in Gee’s Bend, Alabama, or the works by contemporary vanguard artists using fabrics in their wall hangings, or the drawings of Bill Traylor, or photographs of outdoor environmental settings put together with leftover objects, or the assemblages, which might be by pros or by outliers and bespeak religious or political concerns—and so on—the flavor and distinctiveness of the different artists get lost. We can only wonder, moreover, why this vanguard artist, but not that one, was chosen.

The arbitrariness felt in the exhibition’s inclusions is perhaps most striking in the presence of pictures by Marsden Hartley, Cindy Sherman, and Jacob Lawrence. They are the most widely known artists in the show, and a beguiling work of Lawrence’s of children making chalk drawings on the street appears on the jacket of the exhibition’s catalog and its poster. But why exactly are these artists here? Are they vanguardists who absorbed the lessons of outliers? If that is the point it is not very clear, at least in the work of Sherman and Lawrence. Certainly, the three artists can’t themselves be outliers. They were all paid significant attention in their different eras from almost the moment they stepped forth.

Hartley’s very presence makes one question Cooke’s belief that it was American, and rarely European, artists who looked at and were nurtured by self-taught artists. Surely American and European artists were on the same track in this regard. When, in 1913, Hartley was visiting Gabriele Münter and Kandinsky in southern Germany, he was influenced by their own interest in and versions of Bavarian folk art. And in his later years, as he continued to be drawn to the compressed, flattened space and the seemingly simplified, or primitive, appearance of artworks outside the realm of traditional museum cultures, Hartley was little different from Gauguin or Picasso, Beckmann or Derain, Dubuffet or Léger. When Léger came to the States in the early 1930s, he announced that the most profound impression any American painting made on him was an Edward Hicks Peaceable Kingdom.

And when, at the show, one stands before Hartley’s The Great Good Man (1942), one of his portraits of Abraham Lincoln, the whole business of how we label and categorize artists flies out the window. Hartley’s figurative paintings, done in his last years, are hit or miss (he was primarily a landscapist). But in this picture, based on a photograph of the president from around 1862 (and one of the treasures of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts), he created from his feeling for the man a towering and slightly forbidding image. It makes you see why John Nicolay and John Hay, the president’s young secretaries, thinking of their boss at times as an omnipotent ruler, called him “the Tycoon.”

Cooke’s fundamental point seems to be, as she says in her catalog, that we now have, with mainstream professional artists and the self-taught, a “level playing field.” One can have mixed feelings about how she has realized the idea in her show, but her thesis is one we are coming to agree with. It can seem like a secondary matter at this point that Martín Ramírez, say, was a damaged person. When we look at his images of the barren, echoing hills and ravines of California and the American Southwest, it is not hard to wonder, instead, how they stand alongside works by artists who were not outliers. Georgia O’Keeffe put her stamp on the same landscape, and I may not be alone in thinking that Ramírez’s pictures are the more uncanny, affecting, and modern.

Yet there is a hitch in the thought that trained and self-taught creators ought now to be seen together. Some of the most psychologically engaging, and revisitable, works in the National Gallery’s show, whether by Traylor, Castle, or Ramírez—or by Henry Darger (1892–1973), whose emotionally berserk and strikingly designed and colored scenes present brigades of little girls, often with penises, luxuriating in gardens or being attacked by marauders—are works on paper, and such pieces are generally not seen for long, open-ended periods in museums. They are too subject to fading.

The issue, or problem, grows when one adds to the above-mentioned figures other self-taught artists of the same caliber who, although not American and not in the National Gallery’s show, also make mostly works on paper. They would include Eugen Gabritschevsky, Susan Te Kahurangi King (who is in her sixties and from New Zealand), Adolf Wölfli (who was Swiss and spent much of his life in a psychiatric clinic), and a number of others. Why so many major outlier artists work largely with paper, pencils, and pens of differing sorts is no doubt due to the straitened life circumstances some of them have faced. Using paper of any kind was the best or only option, and far more than painting in oils or carving in wood or stone, making a drawing has an immediacy. Though Henry Darger’s watercolors, it is true, called for a process of tracing and sometimes photo-enlarging, his system would have taken far longer if he had painted his complicated scenes in oil. Working on paper as he did, he, like these other artists, could see the story in his head made visible with some speed.

Given the fragility of paper, a considerable aspect of what outliers do may always have about it, at least on the walls of museums, something removed, even private. To go to the American Folk Art Museum’s “Vestiges and Verse” exhibition (or to visit it in its informative catalog), where most of the works are on paper, is to land in a realm of very private, even delusional voices. This is the kind of show that Lynne Cooke’s efforts are meant to supersede. One wonders if, apart from Darger, who is in “Vestiges,” Cooke would see the artists in Valérie Rousseau’s exhibition as being outliers. They seem more mired than “mobile.”

The Folk Art Museum’s show is loosely about the fact that many of these persons have presented their experiences as stories or running accounts of one sort or another. In a ledger from a hospital, for example, James Edward Deeds Jr., an inmate, would for a time make a portrait drawing of some known or imagined person on one page and on the next a little scene or an animal that might relate to that person. Other pieces give us charts of numbers, or of invented creatures, or of systems that might pertain to language. Much of the material is baffling on the face of it; but many of the pieces make us linger because they have been drawn in pristine and exacting ways, or have come alive from endless little alterations.

The pages from the diary of Carlo Keshishian, who is English and in his thirties, are particularly riveting. He writes out his thoughts in letters so small and tightly placed together that from any distance all we see is a near-airless mass of tiny black lines, which seems to undulate as we look at it. The drawings of Susan Te Kahurangi King, which have only begun to be seen in New York, are forceful. She often uses cartoon characters in her scenes, but her disorienting pictures have less to do with popular culture than with choreographing awkward, even impossible relations between bodies, which fly into and out of each other, or seemingly pull themselves inside out. However her efforts are labeled, one wants to see more of them.

Cartoons and comic strips—or a sense of these forms—underlie, finally, the work of the most impressive figures in the exhibition, Darger and Adolf Wölfli. For viewers concerned with outsider art they are among the territory’s old masters. Both have been the subjects of books and have been seen, like Martín Ramírez, who is their equal, in defining and revelatory retrospectives over the last fifteen years at the Folk Art Museum. This doesn’t mean that Wölfli, who died in 1930 at sixty-six, is exactly an embraceable figure. There is a degree of flowing inventiveness and industry in his pictures, which can resemble fantasy versions of carpets, game boards, or aerial views of places, suggesting that the man was on a different wavelength from the rest of us.

With a seeming effortlessness, Wölfli makes organic wholes out of combinations of abstract shapes, geometric patterns, large curving forms, words, musical notations, and bits of the Swiss alpine world he grew up in. Threading his way through these mazes is a kind of comic-strip MC: the artist’s bald, eye-mask-wearing, charming yet insidious alter ego.

Taking in a Wölfli, a viewer feels that only a bit of it can be absorbed at once, and this happens, too, when we stand before one of Darger’s panoramic scenes. Whether he is showing warfare—with troops attacking, explosions on the horizon, and little girls being abducted and strangled—or the artist’s mood is less riled and his sexually ambiguous girl heroines, who are often unclothed, are enjoying a little downtime, Darger’s graphic inventiveness is overwhelming. The life of his work derives from the discrepancy between, on one hand, the repetitiveness and strangeness of his stories and, on the other, the verve and elasticity with which he laid out his cartoon domain.

Wölfli and Darger are very different creators, but both worked with scroll-shaped formats. Darger did so regularly, with his horizontal spreads frequently eight feet wide. Wölfli used the shape merely often, and he could make his similarly long, narrow pictures go vertically or horizontally. This is how Ramírez, who also made long, narrow pictures at times, did it, too. The point may be a small one. Yet few other twentieth-century artists, whether professional or self-taught, employed this format with the same power and consistency.

In time, as outsider, or outlier, artists become more fully recognized and known, we might lose our sense that they are, so to speak, a breed apart. Yet there may always be something distinctive and unusual about the feeling for long and narrow shapes as used by Darger, Wölfli, and Ramírez. The scroll form is one we associate with Asian art. In Western art it can suggest passivity, the exotic, the unfamiliar, or even just traveling. It can connote scenes and stories that go on and on and don’t come to a point. Whatever the form meant to these three artists, they probed its possibilities, and in so doing they widened the scope of twentieth-century art.