The Dancing Bears Park is Europe’s largest sanctuary for bears rescued from captivity. Located in Belitsa, in the Rila Mountains of southwest Bulgaria, it is a major tourist site. The park is managed by Four Paws, an international animal welfare organization that has been liberating circus and performing bears in central and southeastern Europe since the 1990s, when the end of communism in this part of the world gave rise to hopes that bears might enjoy their freedom too.

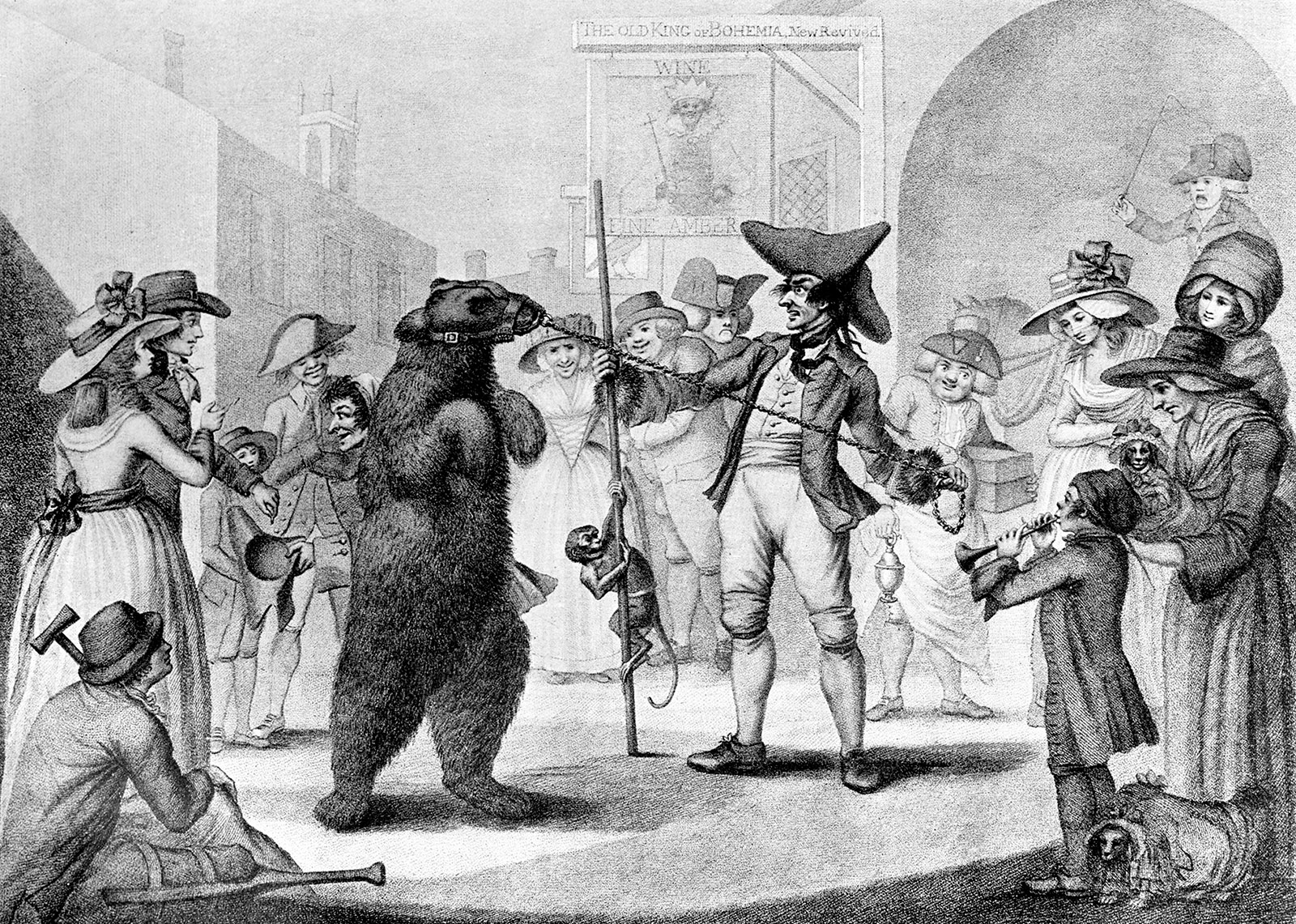

For many decades, if not centuries, young bears had been taken from their mothers in the wild, domesticated by their keepers, and trained to dance by attaching chains to rings driven through their noses and forcing them to step on red-hot sheets of metal. Their owners also beat them and knocked out their teeth. Dancing bears were a popular form of entertainment in villages and towns. They not only danced but performed tricks, imitated celebrities, and even gave back massages, for which their claws were tightly trimmed.

But more damaging in the long term was the way the bears were made to follow human customs, living with their keepers on a diet of white bread and alcohol and working all year round, even in the winter, when they would normally hibernate. The bears lost their natural instincts. They forgot how to hibernate, how to hunt for food, how to attract a mate, even how to move freely. As Four Paws would discover, it was no easy task to teach freedom to animals that had never been free.

In Dancing Bears: True Stories of People Nostalgic for Life Under Tyranny, the award-winning Polish journalist Witold Szabłowski compares the liberation of the Belitsa bears to the emancipation of Europe’s citizens from Communist totalitarianism. In the introduction he describes how he first learned about the park at Belitsa (“an unusual ‘freedom research lab’”) from Krasimir Krumov, a Bulgarian journalist he met in Warsaw:

As I listened to Krumov, it occurred to me that I was living in a similar research lab. Ever since the transition from socialism to democracy began in Poland in 1989, our lives have been a kind of freedom research project—a never-ending course in what freedom is, how to make use of it, and what sort of price is paid for it. We have had to learn how free people take care of themselves, of their families, of their futures. How they eat, sleep, make love—because under socialism the state was always poking its nose into its citizens’ plates, beds, and private lives.

Szabłowski writes in a simple, vivid style, translated well from Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones. His allegory is humorous, ironic, frequently absurd, and sometimes dark, but always full of understanding and compassion for its subjects, both human and animal.

In ten short chapters in the first half of the book, he tells the story of the dancing bears by talking to their captors and their liberators. The keepers do not think they have done anything wrong. They loved their bears, they say, and treated them as family: “I fed her decently, because if she was hungry, she refused to work. She ate eight loaves of bread a day.” This is Gyorgy Marinov, who bought his bear in 1991, when the collective farm in his village collapsed and he lost his job as a tractor driver. “If I could have, I’d have worked at the collective farm to the end of my days. Nice people. The work was tough sometimes, but it was in the open air. We never lacked a thing.”

The owners badly missed their bears when they were confiscated by Four Paws. The organization had the law on its side (the keeping of bears was outlawed when Bulgaria joined the European Union in 2007) but paid the owners compensation for depriving them of their income. One of the oldest bear trainers, Dimitar Stanev, apparently became so ill from longing for his bear, named Misho, that he died.

Retraining bears to become free has to be done gradually. Freedom “can’t be given to them all at once, or they’d choke on it,” Szabłowski learns. First their nose rings are removed. After a few days in an artificial cave, “where they get used to their new situation,” they are put into a special section of the park fenced off from the other bears. The new arrival becomes accustomed “to the smell of the other bears, sees them, and eats its meals close to them, but has no physical contact with them.” Later the bear will be allowed to join the others in a common roaming area surrounded by a high electric fence. Freedom for the bears has its limits.

Within the artificial confines of the sanctuary various attempts are made to stimulate the natural instincts of the bears. Their food is hidden to teach them how to hunt. They are gradually taught to hibernate, with mixed results. But as Szabłowski is told by the sanctuary’s manager, Dimitar Ivanov, it is able to provide only “a semblance of freedom” for the bears, which, if released into the wild, could not survive:

Advertisement

Either they’d die of cold, because they’d be incapable of finding a place to hibernate, or they’d be killed by the first male whose territory they entered. Or they’d start looking for food in trash cans and someone would shoot them.

They had been held captive for too long to have any chance of coping with total freedom.

Some of the bears are so infected with the prisoner mentality that for years they start to dance when they see a human being. “They stand up on their hind legs and start rocking from side to side,” Szabłowski writes. “As if they were begging, as in the past, for bread, candy, a sip of beer, a caress, or to be free of pain. Pain that nobody has been inflicting on them for years.”

The second half of Dancing Bears transfers its attention to the human realm but follows the same form as the first half, with ten chapters, identically titled, each beginning with a quotation from the equivalent chapter in the first part of the book. Szabłowski travels through the former satellite countries of the Soviet Union (“Regime-Change Land,” as he calls it). He starts in Cuba, where he rents a car and offers lifts to anyone who thumbs a ride: farmworkers, soldiers, policemen, nurses, doctors, priests, and children on their way to school. Fidel Castro is dying. People talk about him in an open way, perhaps because they are stirred up and disinhibited by news of his illness. Some love him. One true believer, a smart black woman in a pillbox hat, believes Castro has freed Cuba from enslavement to America:

Thanks to him, we’re the last country that isn’t led on a string by the USA. We have a superb education and health-care system. Nobody’s dying of hunger here. You only have to look at Dominica, or Haiti, which are on America’s leash. They’ve got nothing to eat there.

Others cannot wait for Castro to be dead but are unsure about the freedom afterward. “The fact that Communism has failed is obvious,” one man tells Szabłowski. “But they can’t just introduce capitalism here overnight either—that would be as if someone who hasn’t eaten for ages were suddenly given five hamburgers all at once. The stomach can’t cope with it.”

For millions of people the end of communism meant the loss of secure jobs. Collective farms collapsed and factories and mines were forced to close, leaving rural settlements and towns without work or, in some places, even hope of employment. Many fled abroad, using their new European freedoms to work as cleaners, fruit pickers, plumbers, or taxi drivers in richer EU countries, or in some unlucky cases just to live on the streets there.

Szabłowski meets a homeless Polish woman living in Victoria Coach Station in London. She had lost her job as a machine knitter in Pabianice, could not live on the pension she was given (around $125 a month), and left her rotting village, at first sleeping in railway stations and then traveling by train to Strasbourg because, as she explains, she had read “that Strasbourg is the seat of justice. That Strasbourg helps people who are cheated by the Polish state.” Having failed to make her case to the European Court of Human Rights, she set off for London, because she had been told that it was “swarming with Poles.” The eccentric woman goes by the name of Lady Peron (peron being Polish for a railway platform). She keeps her “treasures” (the ticket to Strasbourg, newspaper clippings, and so on) in a shopping cart, wears dark glasses, and likes piña coladas.

Wherever Szabłowski goes he finds the same reaction to the end of the collective farms: no one wants to work the land. Decades of forced labor for the state had deprived people of the will to work for themselves, as peasant families had done on their farms before collectivization. They became like the dancing bears, whose hunting instinct had been killed by servitude.

On the border between Poland and Ukraine, Szabłowski meets Yevheniya Cherniak, a sixty-year-old Ukrainian woman, who works as a cleaner in Poland, returning every few months to her village in Volhynia, in northwestern Ukraine. She brings back food from Poland because it is better there than in Ukraine, where, she says,

Advertisement

Even though we’ve got the best earth in Europe, it lies fallow. You tell me, Witold, where’s the sense in that? Ukraine could be Europe’s granary. You could eat our black earth with a spoon—there’s no soil like it anywhere in the world. But what happens? It just lies fallow. People are only interested in opportunities to earn money abroad. Or to get something for nothing, just as they got used to doing under the Commies.

When the collective farm in her village closed down, Yevheniya’s husband was given two and a half acres of arable land, not much less than the average peasant smallholding in that area before collectivization; but he did not “feel like” farming it, she says, and took to drink instead: “Unfortunately, the whole Ukrainian nation is just like our marriage. Either they work hard, but abroad, like me. Or they sit in their village and whack a stick against a tree in the hope that a pear might fall.”

The old peasant spirit of enterprise can manifest itself in unexpected ways. With his fine sense of the comic and absurd, Szabłowski tells the story of the Hobbits’ Village set up on the site of a former PGR—Państwowe Gospodarstwo Rolne, or state agricultural farm—in the northern Polish village of Sierakowo Sławieńskie. At first I thought it was a joke, but Google confirmed it with images of people dressed as Tolkien characters standing outside cottages in the theme park. “It’s poverty and unemployment that have brought us out of our houses,” says Gandalf. “Otherwise no one would make such a fool of himself.”

According to Szabłowski, there are many villages “that have found their feet in the twenty-first century” by turning themselves into tourist attractions, into “places known as World’s End, Labyrinths, Fairy Tales, Bicycles, and the Healthy Living Hamlet.” He goes on a tour to them with a group of local community leaders “looking to see if something similar could be set up in their own villages.”

In Belgrade Szabłowski finds a macabre attraction. Pop Art Radovan is a walking tour of the places in the city haunted by Radovan Karadžić, the Serbian leader and war criminal, while he was living in hiding as Dr. Dragan Dabić. Disguised by a white beard and a ponytail, he used cosmic energy to heal his patients, none of whom had any idea who he was. “This is an apolitical tour,” insists the young tour guide, a small girl when Karadžić was laying siege to Sarajevo and ordering the Srebrenica massacre. She takes the small group of tourists to the supermarket where the mass killer did his shopping, to the pancake house where he ate several times a week, and to the bar where he liked to sit underneath the portrait of himself as president, she tells them, and drink Bear’s Blood, his favourite wine.

The final chapters of this jewel of a book seem to be suggesting that the ghosts of communism are not dead. In Gori, Georgia, the birthplace of Stalin, Szabłowski pays a visit to the Stalin Museum, recently restored to all its glory as a Soviet shrine, and listens to the women who work there. He quotes them without commentary:

When I was at college, we were still taught that Stalin was an outstanding statesman. But the system changed, the curriculum changed, and now I have to teach that he was a tyrant and a criminal. I don’t think that’s true. The resettlements? They were necessary for people to live in peace. The killings? He wasn’t responsible for them—it was Beria. The famine in Ukraine? That was a natural disaster.

I used to work at a clothing factory. In the personnel department too. When the Soviet Union collapsed, the factory collapsed with it. And everything was looted—even the glass was stolen out of the window frames. In Stalin’s day something like that wouldn’t have been possible. The culprits would have been punished. So these days when I hear the stories they tell about him, I say, “People, you’ve lost your minds. Remember the Soviet Union. Everyone had work. The children had a free education. From Tbilisi to Vladivostok.”

The book ends in Athens. It is 2010, and the city has been taken over by demonstrations and riots against austerity. People have lost jobs. They blame the Germans for their problems. In Exarcheia, a district full of anarchists, Communists, and Trotskyists, “it’s hard to find a patch of wall…that’s free of graffiti.” The police do not venture there. The rebels tell Szabłowski that they’re starting something “that will reshape the whole of Greece.”

“So what do you want to change?”

“We want to do away with capitalism. And after that we’ll see. You’ll realize we’re starting a landslide here that will engulf the entire world.”

Although this quotation, the last words in Dancing Bears, may be read as a warning, there are no simple messages in Szabłowski’s allegory. The great strength of his book is its nuanced understanding of the reasons why so many people are nostalgic for the way of life they lost when Soviet communism disappeared. He shares some of their regrets, judging from an interview he gave to the Polish website naTemat.pl about an experiment he had carried out with his wife and child. For six months they had lived as if they were in Communist Poland in the early 1980s, renting three rooms in an old apartment bloc and using only household items from those times.1 Recognizing the stupidity of the Communist system, Szabłowski nevertheless told the website that he thought relations between people had been better then. They were more communicative than they are today, he said, when people have been isolated from one another by their smartphones and headphones; they had more time for one another. In Communist times an unexpected visit by a friend was normal, but today that rarely happens, because people’s time is planned and even friends are allocated slots in their schedule.

Such ideas are not confined to post-Communist societies, of course. Many of us would probably agree with them. But they reinforce a powerful nostalgia among those who lived as adults in the Communist system. Materially, people did not have a lot. But they had a strong collective sense forged by living in communal apartments, by their workplace and activities in clubs, and, not least, by the propaganda system, which encouraged a belief in their collective achievements led by a paternal party-state. Looking back at the Communist period, older people in particular are inclined to view it as a time when values such as comradeship and public duty mattered more.

The capitalist system, by comparison, can seem harsh and uncaring—a system in which money is the only value that matters—particularly in the lawless and rapacious form that it developed in the former Soviet Union after 1991, when reckless privatization in terrible conditions of hyperinflation ensured that the country’s wealth would end up in the hands of a bunch of ruthless oligarchs. In a few years, these older people witnessed the collapse of everything they had: guaranteed employment, life savings, health and housing benefits, an ideology that gave them moral certainties, and pride in their country and its achievements. No wonder they felt some regret for the disappearance of the Soviet Union. It had been their world.

The thing that really needs explaining is the Soviet nostalgia manifested by a growing number of the young—by people who had not been born when the Soviet Union existed. In Russia, for example, a country that does not appear in Dancing Bears, a survey carried out in October 2016 found that 27 percent of those aged eighteen to twenty-four regretted the collapse of the Soviet Union (among those over sixty it was 85 percent). For these young people the USSR can only be a fantasy, a legendary civilization that they imagine to have been better than it actually was; a mythic past they prefer to the present, when one in six of them is likely to be unemployed. For them the Soviet Union is a sort of counterculture through which they are able to express their discontent in a politically acceptable manner. Soviet nostalgia is everywhere in Putin’s Russia—in TV shows and films, pop songs, clothing, badges, in retro Soviet restaurants, brands of candy and alcohol, even toys and games resurrected from the Soviet era.

None of this suggests that people want to go back to the Soviet Union. Their nostalgia is “reflective” rather than “restorative,” to use the terms of Svetlana Boym,2 a generalized longing for a lost era that may express dissatisfaction with the contemporary world but does not amount to an actual desire to restore that mythic past. We are not, in other words, about to face a revanchist movement for the revival of the Soviet Empire based on these political yearnings. What we are seeing suggests rather that the end of communism left an ideological and moral vacuum, and that many people feel unable to adapt to the new capitalist realities in post-Communist societies. Anxious and confused, they are not used to thinking or working for themselves. They yearn for the old certainties.

Perhaps, in the end, human beings are more like bears than we imagine. Their ways of thinking and behavior can be permanently altered by conditioning. As the manager of the Belitsa sanctuary puts it of his dancing bears:

For twenty or thirty years they were used to having somebody do the thinking for them, providing them with an occupation, telling them what they had to do, what they were going to eat and where to sleep. It wasn’t the ideal life for a bear, but it was the only one they knew.

This Issue

July 19, 2018

Tipping the Scales

Düssel…

A Work of Art

-

1

They wrote a book about it: Witold Szabłowski and Izabela Meyza, Nasz mały PLR. Pół roku w M- 3 z trwałą, wąsami i maluchem [Our Little Polish People’s Republic: Six Months in a Three-Room Apartment with a Perm, a Mustache and a Fiat 126p] (Kraków: Znak, 2012). ↩

-

2

See her The Future of Nostalgia (Basic Books, 2001). ↩