California, and Los Angeles in particular, is a story we tell ourselves—a projection of our most indulgent fantasies of what life could be if unburdened by adult responsibilities. We tell this story in movies, of course, and through music and magazine spreads, but it’s similarly communicated by the distinctive architecture dotting the city’s many boulevards. Mission-style mansions and beachside bungalows assert the promise of Hollywood glamour and a sun-drenched endless summer.

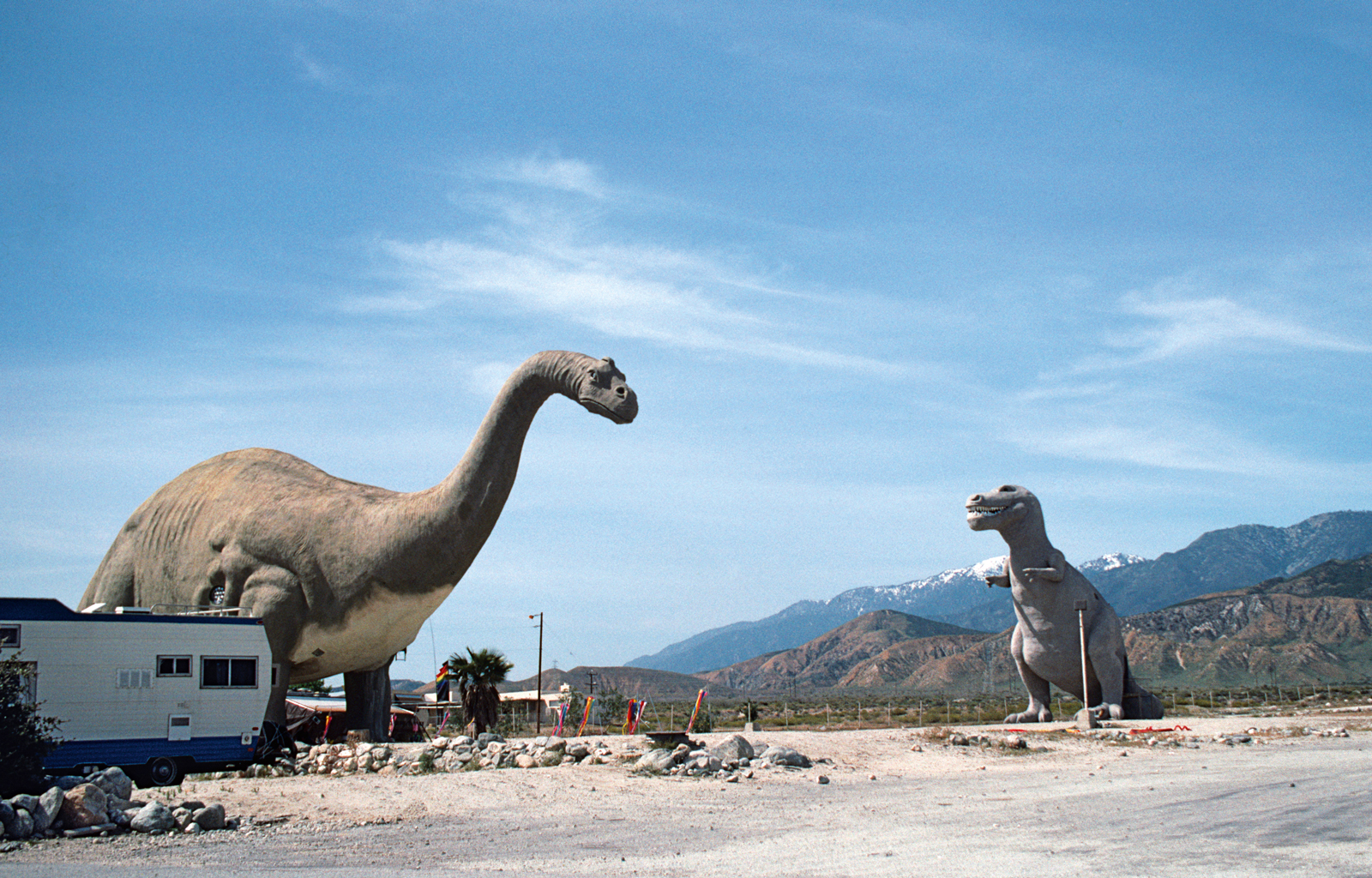

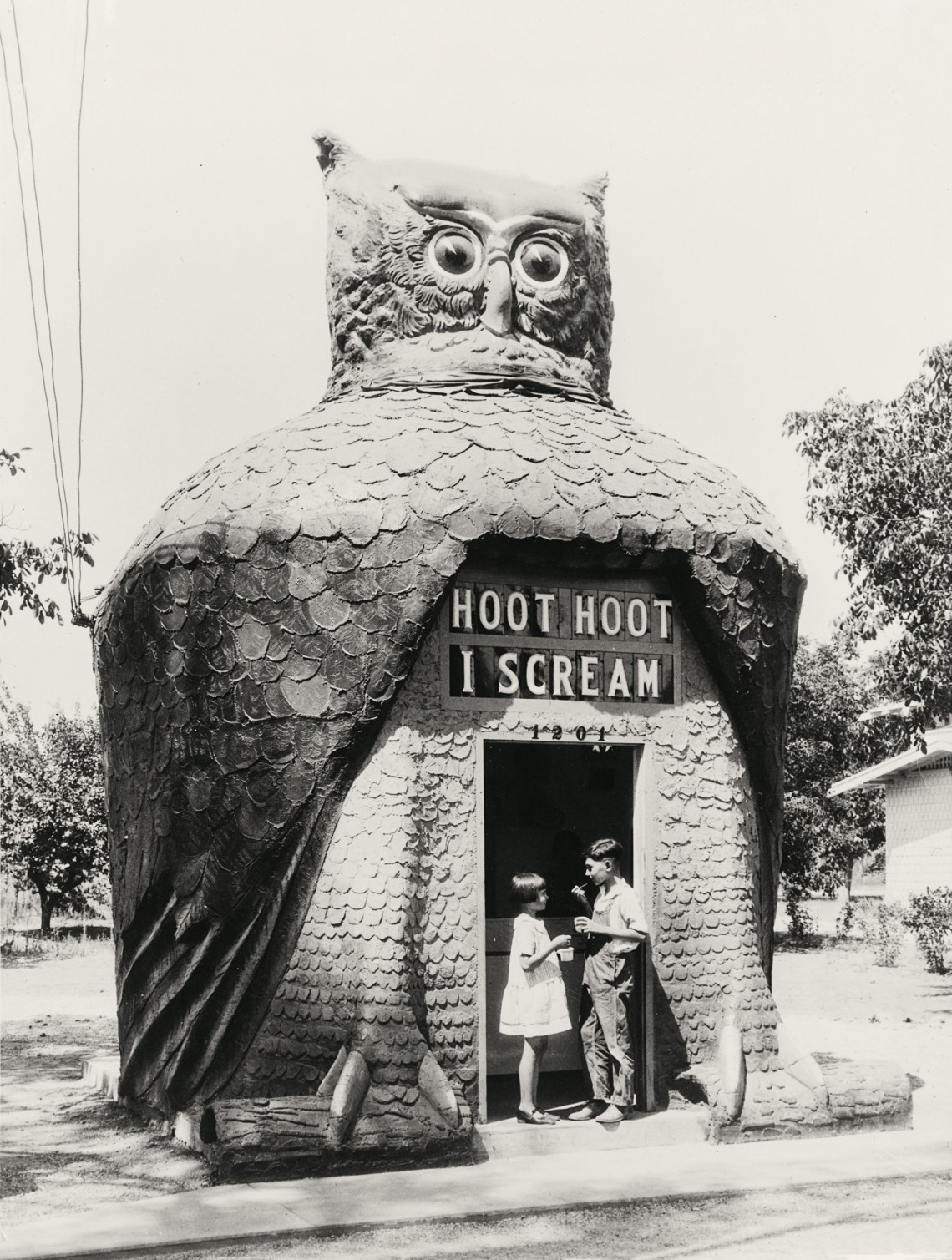

The California myth is perhaps most overt in the so-called “programmatic” or novelty roadside architecture of the early twentieth century, the massive plaster animals and igloo-shaped buildings that line the freeways, beckoning passersby to stop for a photo-op or a snow cone on a hot day. These attractions are the focus of the recent reprint of Jim Heimann’s California Crazy: American Pop Architecture, a survey of fantastic buildings designed to look, for example, like a wide-eyed owl or a frog preparing to leap; more familiar examples include the gigantic dappled donut perched atop a small donut shop in Inglewood, or the dinosaurs that famously roam the I-10 en route to Palm Desert. Such buildings make the city in their image, a spectacular playground dreamed up by entrepreneurs with a penchant for plaster.

California Crazy, which was originally published in 1980 and republished in 2001 and now again this year, tells the story of American novelty architecture through brief thematic essays written by Heimann, as well as a more extensive architectural history written by the late David Gebhard. The book traces the origins of programmatic architecture—so called because the buildings are shaped to resemble the product or service sold inside—to the cultural influence of Victorian amusement parks and early Hollywood.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the expansion of railroad routes in the Los Angeles area engendered a series of land booms and a period of rapid architectural development. Heimann argues that programmatic architecture became popular in southern California because real estate boosters marketed the region as an empty canvas at a time when most American cities had already been developed. “What Los Angeles lacked in history,” Heimann writes, “it made up for with space… and an optimistic attitude that anything was possible.” It was at this time that the newly-emerging Hollywood studios began building their film sets throughout the city, inspiring small business owners and developers to design buildings that could match their visual appeal.

But as the book’s illustrations make clear, novelty architecture is not always so innocuous and wholesome. Take Clifton’s, the cafeteria-style restaurant founded in 1931 and reopened in 2015 after a fourteen-year hiatus. Walk into Clifton’s and be transported to a paragon of prewar kitsch: each of the building’s five floors is painstakingly decorated with taxidermized animals and extravagant foliage, like a miniature golf course come to life. It’s a wonderful place to pair a martini with a ramekin of Jell-O. Historian David Gebhard discusses the enduring popularity of the restaurant and its imaginative facade, but the Pacific Seas bar on the restaurant’s fourth floor is arguably Clifton’s most beloved feature. It is an approximation of the Tiki bar, a familiar vestige of novelty twentieth-century architecture. And its recent resurgence suggests that the programmatic style is making a comeback. In many ways, California Crazy makes this comeback feel natural. Who wouldn’t want to be served lemonade from a giant plaster lemon? Why shouldn’t all drive-thrus be built to resemble fifteen-foot tall tamales? But the revival of these novelty styles is revealing, suggesting that much of the allure of vintage vernacular is its connection to the fantasy of escaping one’s reality—a fantasy that, in the case of the Pacific Seas at Clifton’s, relies on culturally appropriated visuals. California Crazy misses the opportunity to discuss the nuances of this appropriation, instead appearing to conflate the exotic appeal of a building shaped like an ice cream cone with that of, for example, a Tiki bar, or of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, which is built to resemble a stylized pagoda.

Such provocative juxtapositions are many in California Crazy. In his chapter “From Amusement Zones to the Road,” Heimann includes a photograph of the African Dip building from the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, in which white contestants could pay to throw balls at a target and dunk a black person into a tank of water. A sculpture of an African woman comprises the building’s facade, her nose ring dangling over her disproportionally large lips and bright white teeth. On the adjacent page, another photograph from the Exposition shows a colossal plaster Uncle Sam leaning similarly over the roof of the fair’s Souvenir Watch Palace. In lieu of a nose ring, Sam wears a pocket watch that he dangles over a row of patriotic caryatids. It is a strong juxtaposition, and the irony of the formal similarities between such contrasting images reads as intentional. But rather than addressing the ways in which the fair’s novelty buildings reflected and reinforced cultural attitudes toward race, California Crazy treats them, in what feels like a missed opportunity, as comparable examples of how its “Joy Zone” architecture came to influence Hollywood set design.

Advertisement

More chilling, perhaps, is that the conspicuous racism of the African Dip building is echoed in the novelty structures that we continue to use and celebrate. The Mayan Theatre, with its façade covered in faux pre-Columbian sculpture and patterning, was built in Los Angeles in 1927 and recently designated a historical monument, converted from a movie theater to a popular nightclub. Gebhard writes that the cartoonish non-western aesthetic of theaters like the Mayan or Grauman’s Chinese “was openly employed to carry the theater-goer into an intermediary non-everyday world, and thence into the visual mythology of the film.” But inherent in this idea of a generalized escapism is the othering of the culture in question—and a gross approximation of it, rather than a specific and careful understanding. Like so much Americana, programmatic architecture represents, on the one hand, a charming example of vernacular design and kitsch. But as the images in California Crazy attest, such buildings also reveal the unexpected ways in which cultural appropriation and racial stereotyping are built into the fabric of our entertainment culture—in this case literally structuring it.

Jim Heimann’s California Crazy: American Pop Architecture is published by Taschen.