Peter Handke says: “No matter what happened my mother seemed to be there, openmouthed.” You were not there. Your mouth wasn’t even open, because you had lost the luxury of astonishment and horror, nothing was unexpected anymore because you no longer had any expectations, nothing was violent because violence wasn’t what you called it, you called it life, you didn’t call it, it was there, it was.

2004 or maybe 2005. I’m twelve or thirteen. I’m walking around the village with my best friend Amélie and we find a cell phone on the ground, on the asphalt. It was just lying there. Amélie was walking along and she tripped on it. The phone went skittering down the road. She bent down, picked it up, and we decided to keep it to play with, to send messages to the boys Amélie met online.

Within two days the police called to tell you I’d stolen a phone. I found the accusation overblown: we hadn’t stolen anything, it was there on the street, by the side of the road, we didn’t know who it belonged to. But you seemed to believe the police more than you believed me. You came to my room, you slapped me, you called me a thief, and you took me to the police station.

You were ashamed. You looked at me as if I had betrayed you.

You didn’t say anything in the car, but once we were sitting before the policemen, in their office plastered with incomprehensible posters, you were quick to defend me, with a forcefulness I’d never heard in your voice or seen in your eyes.

You told them that I would never have stolen a phone. I had found it, that’s all. You said that I was going to become a professor, or an important doctor, or a government minister, you didn’t know what yet, but in any case that I was going to get a degree and I had nothing to do with delinquents [sic]. You said you were proud of me. You said you had never known a kid as smart as I was. I had no idea that you thought all those things (that you loved me?). Why had you never told me?

Several years later, once I’d fled the village and gone to live in Paris, when I went out at night and met men in bars and they’d ask how I got along with my family—it’s an odd question, but they ask it—I would always tell them I hated my father. It wasn’t true. I knew I loved you, but I felt a need to tell other people that I hated you. Why?

Is it normal to be ashamed of loving someone?

When you’d had too much to drink, you’d lower your eyes and say that no matter what you loved me, that you didn’t know why you were so violent the rest of the time. You would cry, admitting that you couldn’t make sense of the forces that came over you, that made you say things you’d instantly regret. You were as much a victim of the violence you inflicted as of the violence you endured.

You cried when the twin towers collapsed.

Before my mother you’d been with a woman named Sylvie. You had tattooed her name on your arm, yourself, in India ink. When I asked you about her, you wouldn’t answer my questions. The other day a friend said, because I’d been talking about you, Your father doesn’t want to go into his past because the past reminds him that he could have become a different person, and didn’t. Maybe he’s right.

Those times I got in the car to ride along with you when you went to buy cigarettes, or something else, but usually and very often cigarettes, you’d put a pirated Céline Dion CD on the stereo—you’d written Céline on it in blue marker—you’d slip in the disc and you’d sing at the top of your lungs. You knew all the words by heart. I’d sing with you, and I know it’s a cliché, but it’s as if in those moments you could tell me things you could never tell me at any other time.

You used to rub your hands together before you ate.

When I bought sweets at the village bakery, you’d take one from the bag with a little guilty look, and you’d say: Don’t tell your mother! All of a sudden you were the same age as me.

Advertisement

One day, you gave my favorite toy, a board game called Doctor Maboul, to the next-door neighbor. I played with it every day, it was my favorite game, and you’d given it away for no reason. I howled, I begged to have it back. You only smiled and said, That’s life.

One night, in the village café, you said in front of everyone that you wished you’d had another son instead of me. For weeks I wanted to die.

2000. I remember the year because the Y2K decorations were still up around the house: crepe paper, colored lights, the scribbly drawings I’d brought home from school with gold letters spelling out good wishes for the new year and the dawn of the new millennium.

It was just you and me in the kitchen. I said, Look Papa, I’m an alien! and I made a face using my fingers and tongue. I never saw you laugh so hard. You couldn’t stop laughing, you were gasping for air. Tears were running down your cheeks, which were bright, bright red. I’d stopped making my alien face but still you went on laughing. You laughed so hard that after a while I started to worry, frightened by this laughter that wouldn’t stop, as if it wanted to go on for ever and echo to the end of the world. I asked why you were laughing so hard, and you answered, between two laughs, You’re the damnedest kid I’ve ever seen, I don’t know how I could have made a kid like you. So I decided to laugh with you. We laughed together, clutching our bellies, side by side, for a very, very long time.

The problems had started in the factory where you worked. I described it in my first novel, The End of Eddy: one afternoon we got a call from the factory informing us that something heavy had fallen on you. Your back was mangled, crushed. They told us it would be several years before you could walk again, before you could even walk.

The first weeks you stayed completely in bed, without moving. You’d lost the ability to speak. All you could do was scream. It was the pain. It woke you and made you scream in the night. Your body could no longer bear its own existence. Every movement, even the tiniest shift, woke up the ravaged muscles. You were aware of your body only in pain, through pain.

Then your speech returned. At first you could only ask for food or drink, then over time you began to use longer sentences, to express your desires, your cravings, your fits of anger. Your speech didn’t replace your pain. Let’s be clear. The pain never went away.

Boredom took up all the space in your life. Watching you, I came to see that boredom can be the hardest thing of all. Even in the concentration camps a person could get bored. It’s strange to think about: Imre Kertész says so, Charlotte Delbo says so, even in the camps, even with the hunger, the thirst, the death, an agony worse than death, the ovens, the gas chambers, the summary executions, the dogs always ready to tear a prisoner limb from limb, the cold, the heat, and the dust in the mouth, the tongue hardened to a scrap of cement in a mouth deprived of water, the desiccated brain contracting within its skull, the work, the never-ending work, the fleas, the lice, the scabies, the diarrhea, the never-ending thirst, despite all of it, and all the other things I didn’t name, there was still room for boredom—the wait for an event that will never come or has been too long in coming.

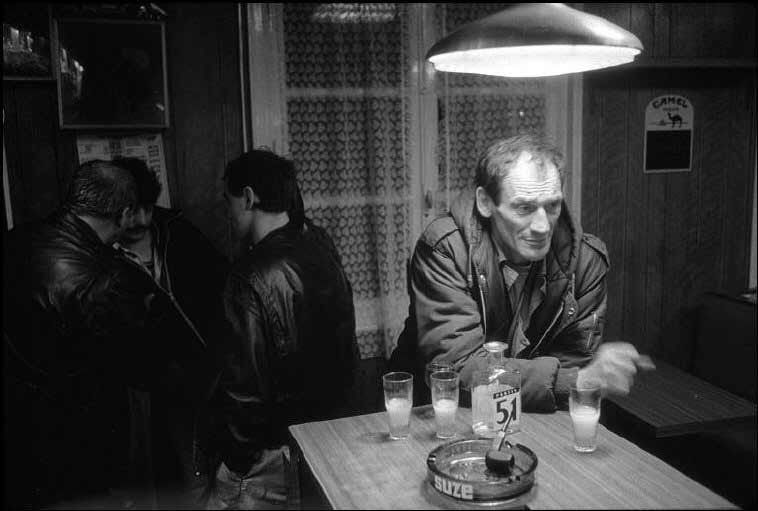

You’d wake up early in the morning and turn on the TV while you lit your first cigarette. My room was next door. The odor of tobacco and the noise drifted in to me as the odor and noise of your being. The people you called your buddies would come drink pastis at our house in the late afternoon. You’d watch TV together. You’d go to see them from time to time, but more often, because of your back pain, because your back had been mangled by the factory, mangled by the life you were forced to live, by the life that wasn’t yours, that wasn’t yours because you never got to live a life of your own, because you lived on the outskirts of your life—because of all that you stayed at home, and usually they were the ones who came over. You couldn’t get around anymore. It hurt too much to move.

Advertisement

In March 2006, the government of Jacques Chirac, then eleven years in office as president of France, and his health minister Xavier Bertrand, announced that dozens of medications would no longer be covered by the state, including many medications for digestive problems. Because you’d had to spend your days lying flat since your accident, and because you had bad nutrition, digestive problems were a constant for you. Buying medicine to relieve them became more and more difficult. Jacques Chirac and Xavier Bertrand destroyed your intestines.

Why do we never name these names in a biography?

In 2007, presidential candidate Nicolas Sarkozy leads a campaign against what he calls les assistés, those who, according to him, are stealing money from French society because they don’t work. He declares: The worker… sees the assisté doing better than he is, making ends meet by doing nothing. What he was telling you was that if you didn’t work you didn’t belong, you were a thief, you were a deadbeat, you were what Simone de Beauvoir would have called a useless mouth. He didn’t know you. He had no right to think that: he didn’t know you. This kind of humiliation by the ruling class broke your back all over again.

In 2009, the government of Nicolas Sarkozy and his accomplice Martin Hirsch replace the RMI—a basic unemployment benefit provided by the French state—with the RSA. You qualified for the RMI because you could no longer work. The shift from the RMI to the RSA was supposed to incentivize a return to employment, as the government put it. In truth, from that moment on, the state harassed you to go back to work, despite your disastrous unfitness, despite what the factory had done to you. If you didn’t take the jobs they offered—or rather, forced on you—you would lose your right to welfare. The only jobs they offered you were part-time, exhausting, manual labor in the large town twenty-five miles from where we lived. Just getting there and back cost you three hundred euros a month in gas. Then, after a certain period, you were forced to take a job as a street sweeper in another town, making seven hundred euros a month, spending all day bent over gathering up other people’s trash—bent over, even though your back was destroyed. Nicolas Sarkozy and Martin Hirsch were breaking your back.

You understood that, for you, politics was a question of life or death.

One day, in the fall, the back-to-school subsidy granted each year to the poorest families—for school supplies, notebooks, backpacks—was increased by nearly one hundred euros. You were overjoyed, you called out in the living room: “We’re going to the beach!” and the six of us piled into our little car. (I was put into the trunk, like a hostage in a spy film, which was how I liked it.)

The whole day was a celebration.

Among those who have everything, I have never seen a family go to the seashore just to celebrate a political decision, because for them politics changes almost nothing. This is something I realized when I went to live in Paris, far away from you: the ruling class may complain about a left-wing government, they may complain about a right-wing government, but no government ever ruins their digestion, no government ever breaks their backs, no government ever inspires a trip to the beach. Politics never changes their lives, at least not much. What’s strange, too, is that they’re the ones who engage in politics, though it has almost no effect on their lives. For the ruling class, in general, politics is a question of aesthetics: a way of seeing themselves, of seeing the world, of constructing a personality. For us it was life or death.

In August 2016, during the presidency of François Hollande, the minister of labor Myriam El Khomri, with the support of the prime minister Manuel Valls, passed what was called the labor law. This law made it easier for businesses to fire an employee, and it allowed them to increase the work week by several hours beyond existing limits.

The company for which you swept streets could now ask you to sweep even longer hours, to spend more of every week bent over a broom. The current state of your health, the fact that you can hardly move or breathe, that you can’t live without the assistance of a machine, are largely the result of a life of repetitive motions at the factory, then of bending over for eight hours a day, every day, to sweep the streets, to sweep up other people’s trash. Hollande, Valls, and El Khomri asphyxiated you.

Why do we never name these names?

May 27, 2017. In a town in France, two union members—both in T-shirts—are complaining to president Emmanuel Macron in the middle of a crowded street. They are angry, that much is clear from how they talk. They also seem to be suffering. Emmanuel Macron dismisses them in a voice full of contempt: You’re not going to scare me with your T-shirts. The best way to afford a suit is to get a job. Anyone who hasn’t got the money to buy a suit he dismisses as worthless, useless, lazy. He shows you the line—the violent line—between those who wear suits and those who wear T-shirts, between the rulers and the ruled, between those who have money and those who don’t, those who have everything and those who have nothing. This kind of humiliation by the ruling class brings you even lower than before.

September 2017. Emmanuel Macron condemns the “laziness” of those in France who, according to him, are blocking his reforms. You’ve always known that this word is reserved for people like you, people who can’t work because they live too far from large towns, who can’t find work because they were driven out of the educational system too soon, without a diploma, who can’t work anymore because life in the factory has mangled their back. We don’t use the word lazy to describe a boss who sits in an office all day ordering other people around. We’d never say that. When I was little, you were always saying, obsessively, I’m not lazy, because you knew this insult hung over you, like a specter you wished to exorcize.

There is no pride without shame: you were proud of not being lazy because you were ashamed to be one of those to whom that word could be applied. For you the word lazy is a threat, a humiliation. This kind of humiliation by the ruling class breaks your back again.

Maybe those who read or listen to these words won’t recognize the names I have just mentioned. Maybe they’ll already have forgotten them, or will never have heard of them, but that is precisely why I want to mention them here, because there are murderers who are never named for their murders. There are murderers who avoid disgrace thanks to their anonymity or to oblivion. I am afraid, because I know the world acts under cover of darkness and night. I refuse to let these names be forgotten. I want them to be known now and forever, everywhere, in Laos, in Siberia and in China, in Congo, in America, beyond every ocean, deep within every continent, across every border.

Is everything always forgotten in the end?

I want these names to become as indelible as those of Adolphe Thiers, of Shakespeare’s Richard III, of Jack the Ripper.

I want to inscribe their names in history, as revenge.

August 2017. The government of Emmanuel Macron withdraws five euros per month from the most vulnerable people in France: it reduces—by five euros—the housing subsidies that allow France’s poorest people to pay their monthly rent. The same day, or a day or two later, the government announces a tax cut for the wealthiest in France. It thinks the poor are too rich, and that the rich aren’t rich enough. Macron’s government explains that five euros per month is nothing. They have no idea. They pronounce these criminal sentences because they have no idea. Emmanuel Macron is taking the bread out of your mouth.

*

Macron, Hollande, Valls, El Khomri, Hirsch, Sarkozy, Bertrand, Chirac. The history of your suffering bears these names. Your life story is the history of one person after another beating you down. The history of your body is the history of these names, one after another, destroying you. The history of your body stands as an accusation against political history.

*

You’ve changed these past few years. You’ve become a different person. We’ve talked, a lot. We’ve explained ourselves. I’ve told you how I resented the person you were when I was a child—how I resented your hardness, your silence, the scenes that I’ve just described—and you’ve listened. And I have listened to you. You used to say the problem with France was the foreigners and the homosexuals, and now you criticize French racism. You ask me to tell you about the man I love. You buy the books I publish. You give them to people you know. You changed from one day to the next. A friend of mine says it’s the children who mold their parents and not the other way around.

But because of what they’ve done to your body, you will never have a chance to uncover the person you’ve become.

Last month, when I came to see you, you asked me just before I left, Are you still involved in politics? The word still was a reference to my first year in high school, when I belonged to a radical leftist party and we argued because you thought I’d get myself into trouble if I took part in illegal demonstrations. Yes, I told you, more and more involved. You let three or four seconds go by. Then you said, You’re right. You’re right—what we need is a revolution.

Adapted from Who Killed My Father, by Édouard Louis, translated into English by Lorin Stein, and published by New Directions on March 29.