Twenty years after Kenneth Starr delivered to Congress his report recommending the impeachment of President Bill Clinton, the former independent counsel has delivered a second report, in the form of a memoir, condemning Clinton all over again. The new report, however, contains only a few air-brushed examples of the sex scenes that distinguished the graphic original. Starr goes out of his way this time to disparage Hillary Clinton, who went virtually unmentioned in the original report. And there is a great deal of Starr bemoaning what he calls his victimization by the press, supposedly orchestrated by a handful of hostile, unscrupulous aides to the former president.

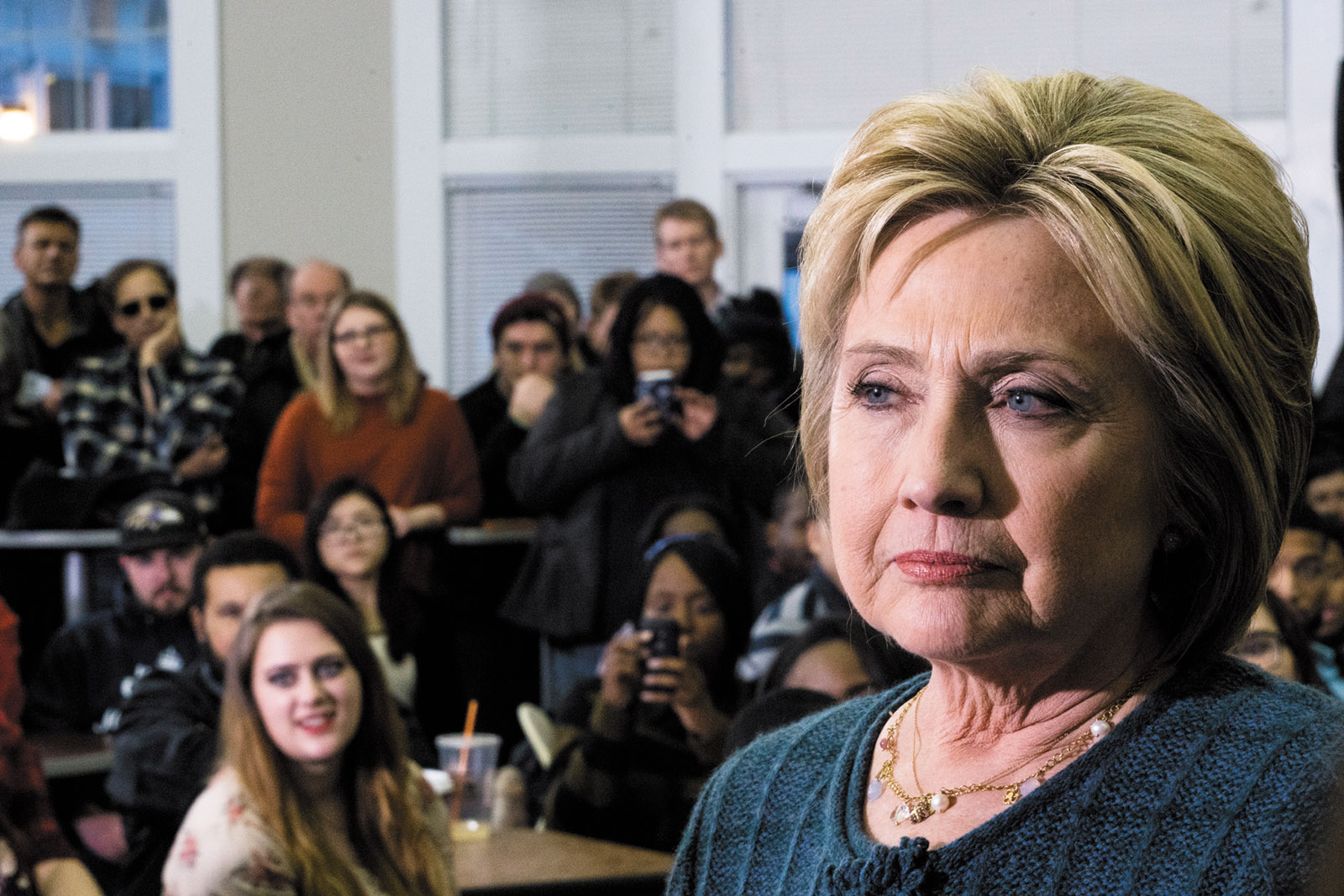

Contempt’s real revelation, however, appears to be inadvertent: long before dissembling about sex became the ostensible subject of the investigation, Starr and his staff’s personal dislike and mistrust of the Clintons, especially of Hillary, hardened into an absolute certainty that they were guilty of lawlessness on a gargantuan scale. The book then shows how that certainty helped turn a faltering right-wing political vendetta against a Democratic president into a constitutional crisis over consensual private behavior.

Starr writes in the belief that history has at last turned in his favor, and that his book can set the record straight and end his reputation as a politically driven inquisitor.1 “The moral compass of the country,” he writes, “has shifted.” Americans—“an indulgent” people in the 1990s—are now less willing to tolerate the alleged sins that justified his investigation of the Clintons. He expects that fair-minded readers will recoil at what he calls the Clintons’ contempt for “our revered system of justice” and Bill Clinton’s “shockingly callous contempt for the women he used for his pleasure.” Whereas his first report repulsed the public, he thinks he can now vindicate what was from the start an extremist effort to hurt and finally topple a sitting president by retrying it once again as a story of mendacity and sex.

In fact all the Clinton scandals, beginning with the Whitewater probe, originated in politics. Conservative Republicans believed that Ronald Reagan’s resounding victory in 1984 had secured for the GOP a lock on the presidency and was proof of a national conservative majority. By that reckoning, despite Clinton’s election by popular plurality in 1992, his presidency was illegitimate. That Clinton was a self-made, white southern baby-boomer, a gregarious, canny Rhodes Scholar with center-left politics and a feminist wife, made the situation all the more galling—and dangerous. Desperate times required desperate measures, lest the Democrats impose their liberal agenda on the nation. (“Whitewater is about health care,” Rush Limbaugh began telling his 20 million listeners in the spring of 1994.)

Even before the Republicans, led by Newt Gingrich, captured the House majority in November 1994—to the right, further proof of Clinton’s illegitimacy—the investigations had been proceeding full throttle. Yet none of the scandals—over Whitewater, the death of White House deputy legal counsel Vincent Foster, firings at the White House travel office, or the alleged criminal mishandling of FBI files—ever amounted to anything.

Clinton’s solid reelection in 1996 further rebuked conservative grandiosity. Private efforts by wealthy right-wingers like Richard Mellon Scaife to turn up dirt produced nothing more than allegations by Paula Jones, a former Arkansas state employee, of a crude sexual advance from Clinton while he was governor. Her lawsuit, backed by anti-Clinton conservatives, was dismissed by federal district judge Susan Webber Wright in April 1998 as “without merit” (although when Jones appealed later that year, a beleaguered Clinton settled for the full amount of her claim). The crusade was sputtering when right-wing operatives tipped off Starr’s office about Clinton’s furtive relationship with the former White House intern Monica Lewinsky, leading to the perjury trap that finally brought about his impeachment. But over the years those political motivations have been all but forgotten while the Lewinsky story has lingered, which allows Starr to claim the moral high ground.

Starr completed his book before his protégé Brett Kavanaugh, a coauthor of the Starr Report, appalled many people during his Supreme Court confirmation hearing with his furious partisan denials of charges of long-ago sexual assault. That irony aside, Starr’s revulsion may strike a chord among the numerous progressives, such as Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, who now assert that Clinton should have resigned over his liaison with Lewinsky. (Lewinsky, who strongly protested at the time that her relations with Clinton were consensual, has recently charged that he abused his power.)

These contemporary attacks from the left, arising in the fraught political climate fostered by Donald Trump, bespeak how sexual politics have changed since the 1990s. But they also show how confused public memory has become about the Clinton impeachment and the politics that drove it.2 Accusations and accusers, for example, that Starr’s unrelenting office investigated and dropped as “inconclusive,” and that its Republican backers knew lacked credibility—including claims by Clinton’s alleged victims Juanita Broaddrick and Kathleen Willey—have been revived as if they were proof of his unrestrained depredations and his wife’s cold-hearted complicity. It is all the more ironic, then, that Contempt illuminates a strain of sexual politics that current arguments over the impeachment have effaced: a traditionalist anti-feminism that, at its angriest, railed against insubordinate “femi-nazis” and that, Starr’s book reveals, informed his investigation.

Advertisement

The memoir affects to defend the honor of women demeaned by the contemptible Bill Clinton. But it more strikingly discloses the contempt and prosecutorial fury that Starr and members of his staff reserved for uncooperative women, above all Hillary Clinton. The Starr team’s scorn for what he derides as Mrs. Clinton’s “in your face” manner fixed their conviction that she, even more than her husband, was a brazen serial liar who lacked the slightest regard for the rule of law. This certitude helped turn the Starr investigation, as the late Anthony Lewis, a liberal columnist for The New York Times and constitutional scholar, wrote in these pages, into something “close to a coup d’état,”3 while the contempt that led Starr and his staff to demonize Hillary Clinton still reverberates in our public life, not least in depictions of her as a harsh, calculating harpy.

Reading Starr’s memoir jogged some memories of my own about the minor part I played in the Clinton impeachment drama. In September 1998 I arrived in Washington to take up a fellowship at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. I began to wonder whether even the most severe of the president’s purported offenses rose to the level of crimes that the framers of the Constitution had in mind when they debated and approved the impeachment clause. Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and I drafted a statement about the constitutional issues at stake. After more than four hundred historians signed on, we published it in The New York Times. That December, I testified along with other historians before the House Judiciary Committee on the constitutionality of the impeachment proceedings.

Once the impeachment reached the Senate, former senator Dale Bumpers, closing the argument in defense of Clinton with what Starr concedes was a “stirring” speech, built his case on the unmet constitutional standards for impeachment and referred directly to the historians’ statement. After hours of closed-door deliberations led to Clinton’s acquittal, Chief Justice William Rehnquist, who presided over the trial, congratulated the senators: he had been “impressed” by their debate “on the entire question of impeachment as provided for under the Constitution.” A couple of weeks later, Senator Edward Kennedy wrote me to say that the historians’ statement, along with a similar statement signed by hundreds of constitutional lawyers, had had a major impact on his colleagues’ discussions.

It was not just personal vanity, then, that led me to expect that Starr’s memoir would seriously address the constitutional issues that surrounded the impeachment—the “entire question” of which Chief Justice Rehnquist spoke. Yet except for a flat assertion that Clinton’s alleged perjury “constituted a ‘high crime or misdemeanor’ within the meaning of the Constitution,” Starr’s book says nothing about those issues. It is surprising to see him simply ignore objections that so badly undermined his case both in the Senate and in the court of public opinion. Absent any thoughtful defense of the impeachment’s constitutional legitimacy, his book cannot rescue his reputation. But the absence is of more than historical significance.

In recent interviews, Starr has rather audaciously suggested that he now thinks the Clinton impeachment was a mistake, that there was not “a consensus among ‘we the people’” that the president deserved removal, as there had been with Richard Nixon. Those remarks might seem bizarre in the face of Contempt’s adamant defense of his actions at the time, but Starr’s point in these interviews has been to refute and ridicule talk of pursuing impeachment proceedings against Donald Trump.

Starr has gone as far as to assert that although Robert Mueller should complete his investigation into Russia’s support for Trump’s election, he has seen “no evidence” that would suggest in the slightest that Trump has committed any “impeachable offenses”—“not even close.” (Trump, gratified by Starr’s supportive remarks, thanked him personally in a tweet.) One wonders what has become of Starr’s earlier standards given the mounting evidence of Russian interference and possible connections to the Trump campaign, including indictments of Trump’s former campaign manager and national security adviser, not to mention his personal attorney and all-purpose fixer, and most recently Roger Stone. One also wonders why, with regard to Mueller’s probe, Starr is now so alarmed about what he recently called “the inherent danger of prosecutorial overreach.”4

Advertisement

Numerous turning points in the long story that led from the alleged Whitewater scandal to Clinton’s impeachment might have produced a very different outcome. Among the first and most important of these events was Starr’s appointment as independent counsel. In July 1994 the Whitewater investigation into the Clintons’ small, passive, and failed 1977 investment in Arkansas real estate, initiated ten months earlier, appeared to be headed toward an imminent conclusion under its original independent counsel, Robert Fiske Jr. A distinguished former federal prosecutor and moderate New York Republican, Fiske had rejected the right-wing conspiracy theories surrounding the Whitewater affair, including the charge that Vincent Foster’s suicide was actually a murder ordered by the Clintons.

The closer Fiske seemed to wrapping up the entire matter and exonerating the Clintons, the more outraged Republicans in Congress and the media demanded his ouster. The release of Fiske’s official finding that Foster had indeed killed himself intensified the GOP hostility. Then a panel of three federal judges (two of them Republicans)—who, under a recent revision in the independent counsel law, had come to control the appointment of the independent counsel—abruptly dismissed Fiske and replaced him with Starr. Himself a well-known federal judge, Starr was a Federalist Society conservative whom many regarded as evenhanded because of his judgment in favor of The Washington Post in a libel case brought by the CEO of Mobil Oil in 1987.

Yet Starr, as he now admits, had consulted with the lawyers for Paula Jones, a fact he did not disclose at the time to the panel that selected him. Nor did he disclose that he was working with the Independent Women’s Forum, a right-wing group for whom he had planned to write an amicus brief in the Jones case. Unlike Fiske, and contrary to the spirit of the independent counsel statute, Starr somewhat frivolously announced that he had no intention of taking on the job full-time. Most glaringly, he had no prosecutorial experience.

Starr, not surprisingly, now claims there was nothing amiss. He rebuffs the well-founded and widely shared suspicions about the motivations of the selection panel—headed by the extremely conservative judge David Sentelle, who owed his appointment to the far-right senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina—as nothing more than falsehoods concocted by White House henchmen. He also repeats the strained argument presented by Republican hard-liners that Fiske’s position was tainted because he had been appointed by Attorney General Janet Reno, who had, of course, been appointed by President Clinton. “To preserve the integrity and independence of the process,” Starr writes, the panel went “looking for a Republican.” But why was that necessary when a Republican was already in charge?

The real problem was that Fiske wasn’t the right kind of Republican to investigate the Clintons, and that he appeared to be concluding an inquiry that would likely clear them of wrongdoing in the Whitewater affair. Conservatives launched attack after attack on Fiske’s integrity. They were desperate for a new independent counsel who would pursue the president and his wife with unflagging fervor. Starr proved equal to the task.5

One of Starr’s first actions after he was installed in August 1994 was to reopen the investigation into Vincent Foster’s death. He defends that decision on the spurious grounds that, as a swirl of paranoid speculation about a possible murder persisted, he had a solemn duty to settle the matter once and for all, above and beyond Fiske’s conclusive report, which he oddly portrays as overly “short, succinct and to the point,” and a reflection of “Fiske’s Yankee personality.” “Leaving any doubt as to the cause of death of a high-ranking Executive Branch official,” Starr writes, “was a recipe for endless conspiracy theories.”

Insisting on his impartiality, Starr describes how he pushed aside a staff member he had initially placed in charge of the renewed inquiry for aggressively promoting and pursuing the right-wing fantasies. (How a conspiracy freak eluded Starr’s vetting is unclear.) Yet he omits that the ensuing investigation, instigated and overseen by the zealous young Brett Kavanaugh, took the conspiracy theories utterly seriously, with the ostensible goal of refuting them beyond cavil, though Starr now says he always thought they were ridiculous. He also omits that his investigators, including Kavanaugh, closely consulted letters, faxes, newspaper clippings, and other communications by and from the fantasists that rehearsed various scenarios and suggested fresh leads and wrinkles in the story.6

It’s not as if Starr was intent on proving that the conspiracy-mongers were correct. But for three years, at a cost to taxpayers of $2 million, his men harassed Foster’s grieving family and friends, and gave license to the right-wing conspiracy machine to spread smears against the Clintons, including rumors, which Starr’s office may have abetted, of a sexual affair between Foster and Hillary Clinton. It quickly became evident that far from refuting the extremists, Starr’s renewed and prolonged investigation was lending their bizarre speculations a kind of official credibility.

Yet only in October 1997 did Starr deliver publicly his conclusions about the case—conclusions no different from those reached by Fiske and the other investigators more than three years earlier.7 His efforts did nothing to impede the lurid propaganda about Foster’s death, which to this day remains an article of faith in the right-wing fever swamps, marketed by the likes of Rush Limbaugh, Sean Hannity, Ann Coulter, and, on the 2016 campaign trail, presidential candidate Trump. I have been unable to discover a single instance over these many years when Starr has stepped forward to contradict the right-wing conspiracy machine and correct that part of the record.

At the time, exploits like the renewed Foster investigation led Starr’s critics to imagine that he was a vindictive, hard-core ideologue. Bumpers, for one, observed that “Javert’s pursuit of Jean Valjean in Les Misérables pales by comparison” to Starr’s pursuit of the Clintons. Apart from flashes of anger at Clinton’s defenders, though, Contempt reveals Starr to be the bland, soft-spoken, self-effacing personality he displays in public—ambitious, certainly, and prone to self-pity, but less an aggressor than someone who reacts to adversity by becoming more rigid and self-righteous, which he projects as a valiant sense of duty.

Another turning point in the impeachment saga came early in 1997 when, barraged by personal attacks and following a major courtroom setback in the Whitewater investigation, Starr announced he had accepted an offer to become a dean at Pepperdine University—“an elegant way,” he recalls, “to exit the investigation.” In his telling, his top prosecutors supported the move, but a “minirevolt” of other staffers reminded him of his “deeply personal and relational” as well as public obligations to stay the course. The tempted man of conscience wavered, but his better angels won out. “Duty had called,” he writes, “and I would honor my commitments, even if it meant remaining in an unpleasant role.”

To underscore his claims to nonpartisan rectitude and responsibility, Starr emphatically denies rumors that “Republican heavies” pressured him to stay: “I got not a single phone call or note saying, in effect, that I shouldn’t abandon ship.” But there were no mere rumors of Republican pressure after his announcement, there were howls of Republican outrage in the political media; and whatever he may or may not have gotten in the mail or over the phone, he suffered a public scolding from William Safire of The New York Times, who had long been spreading tales of Hillary Clinton’s guilt and raising doubts about Foster’s suicide. Right after Starr’s resignation, in a column entitled “The Big Flinch,” Safire ridiculed him as a “wimp” with “a warped view of duty” who was bringing “shame on the legal profession by walking out on his client—the people of the United States.” Having ruined his career, Safire wrote, Starr ought to “get out of town and let someone else finish the job he misled the nation he was prepared to do.” Within forty-eight hours Starr rescinded his agreement with Pepperdine and returned to investigating the president.

On one development after another, through the House’s decision to impeach the president, Starr’s memoir is partial and unreliable. He never once discusses the findings of an authoritative independent study called the Pillsbury Report, after the law firm commissioned by the federal Resolution Trust Corporation, which in April 1995 corroborated the Clintons’ account of Whitewater and concluded with a recommendation “that no further resources be expended on the Whitewater part of the investigation.”

Starr acknowledges that in early 1998 his office learned about Monica Lewinsky on a tip from one of the “elves,” a name coined by one of their number, Ann Coulter, to describe a group of Republican lawyers secretly assisting and directing Paula Jones’s legal team and dedicated to bringing down the president. Members of Starr’s staff had been in contact with the “elves” for months, but the fresh tip initiated a series of rushed events during which Attorney General Reno and the three-judge panel extended Starr’s mandate to include the Lewinsky matter. Starr omits, however, that his office failed to inform the Justice Department or the judges about the origin of the information, the tip’s links to the Jones team, and the long-standing connections between the “elves” and his staff—vital facts that could easily have thwarted the expansion of the probe.

Starr mocks Lewinsky’s first defense lawyer, William Ginsburg—“utterly unqualified”—as well as a proffer that Ginsburg and Lewinsky sent to the independent counsel’s office stating categorically that the president had neither told her to lie nor attempted to obstruct justice by helping her find a job. Had Starr accepted that proffer, as the two members of his staff assigned to Lewinsky initially did, the alleged grounds for impeachment would have been severely diminished; Starr now says Lewinsky “waffled.” Yet Lewinsky never changed her account; she later testified to the grand jury considering Starr’s charges that “no one ever asked me to lie and I was never promised a job for my silence.”

That testimony alone directly refuted the impeachment article on obstruction of justice—yet Starr failed to include it in his report to Congress. Nor does his memoir recall that one of the members of his staff who secured the proffer, Bruce Udolf, was so disgusted by Starr that he refused to sign the official letter rescinding the proffer. Udolf has spoken out about Starr’s unprofessional conduct. “This case”—involving Monica Lewinsky—“should’ve been dead on arrival,” he recently told the Slate podcast Slow Burn. “And it served no useful purpose.” While Starr lavishes praise on his staff for their untiring service, he neglects to mention that one of his chief prosecutors, the hard-charging Jackie Bennett, posted a chart in the independent counsel’s office that listed the less devoted members of the team—including Udolf and Michael Emmett, the other prosecutor who accepted the proffer—under the category “Commie Wimps.” Bennett commended the more stalwart anti-Clinton members of the staff under the title “the Likud faction.”

According to the memoir, Starr’s convictions about the Clintons’ turpitude formed as early as 1995, long before the world learned of Lewinsky, when he and his staff began deposing both Clintons in connection with the Whitewater deal. The first two of these deposition meetings—the president and the first lady would each offer sworn testimony six times between 1994 and 1998—fixed the Clintons, especially Hillary, in the prosecutors’ minds as ruthless deceivers.

It took little questioning during the very first session about Whitewater for one member of Starr’s staff to claim that the president was “a lying dog.” Starr agreed. Clinton’s statements “defied credulity,” he now writes. He even believed that Clinton might have committed perjury, which might have been grounds for impeachment then and there. But he had no actual evidence of falsehood or any other wrongdoing, and although the president piqued the prosecutors’ hostility, he at least came across to them as a charming scalawag, pleasantly bobbing and weaving his way through the questioning.

“When Hillary arrived,” Starr observes, “it was a different story.” Starr considered Hillary Clinton a rude and power-hungry radical who had “absorbed many of [the] ideas” of Saul Alinsky, the Chicago community organizer whose nefarious influence the right traced to both Hillary Clinton and, later, Barack Obama. Indeed, Starr asserts that once they had reached the national stage, “the Clintons often deployed Alinsky’s strategies,” a fantastic claim for which he offers no examples.

But the first lady compounded her sins during the depositions by failing to defer to or otherwise conceal her distaste for the prosecutors and their prosecution. She was all business, Starr writes, “no small talk”; “she made no effort to be cordial.” Her replies to questions were “glib,” “superficial,” and “almost ‘in your face,’ alternating on the theme of profound memory loss.” Over one hundred times in one three-hour session, he charges, she claimed that she could not remember something, a “preposterous” performance that “suggested outright mendacity.” When it was over, Starr recalls, one staff member called her “affirmatively dislikable”; another senior prosecutor gave her a grade of “F minus” to the president’s “C.” “What was clear,” he concludes, “was that Mrs. Clinton couldn’t be bothered to make it appear as if she were telling the truth.”

Starr now says he was “upset” by Hillary Clinton’s “performance.” But was it really so difficult to understand? Clinton always insisted that she knew little about the Whitewater investment. The weight of the evidence would finally indicate that this was so; the Pillsbury Report, ignored by Starr, demonstrated as much around the time of the first depositions. Yet Clinton was being asked to respond, under oath, to questions from prosecutors she reasonably believed were unfriendly, about a labyrinth of financial dealings from ten to fifteen years earlier. Starr slants the evidence when he reports that “Hillary’s extraordinary lapses of memory—especially for a lawyer and self-described policy wonk—were not credible.” In fact she most frequently responded “I don’t know,” which would have accorded with her genuine lack of knowledge and not with some feigned failure to recall.

Starr seems to think it is enough to report his own view of Hillary Clinton as “fundamentally dishonest” in order to establish that she is a remorseless liar, all the more distressing because of her lack of amiability and refusal to play nice. But he offers no evidence that she made any false statements in her hours of testimony. Had she taken the slightest liberty with the truth, he would have had more than adequate grounds to bring charges of perjury or felony false statement. (One of the more surprising revelations in Contempt is that Starr actually considered indicting her in 1998, before conceding that no impartial jury would convict her.)

Along the way, Starr’s office had run into difficult, uncooperative women other than Hillary Clinton whom it regarded with similar contempt but was able to handle more roughly. Susan McDougal, the ex-wife of the eccentric progenitor of the Whitewater project, Jim McDougal, refused to testify before the grand jury, fearing that saying anything other than what she believed the independent counsel’s office wanted would lead to her indictment for perjury. She wound up serving eighteen months in prison for civil contempt of court, eight of them in solitary confinement. Then, upon her release, Starr had her indicted on criminal charges of contempt of court (which ended in a hung jury) and obstruction of justice (which ended in an acquittal). Julie Hiatt Steele contradicted claims by her friend Kathleen Willey concerning an alleged inappropriate advance by the president. Starr accused her of obstruction of justice and making false statements, which led to a mistrial, whereupon the matter was dropped—but only after Steele had been harassed over the adoption of a Romanian child.

But as Starr’s memoir makes clear, his office had a singular disgust for the first lady, the focus of the most powerful and lasting sexual politics of his entire inquest. The right-wing-provocateur-turned-Clinton-supporter David Brock tells of watching the 1997 State of the Union speech on television at Laura Ingraham’s house with a group of friends including Brett Kavanaugh. At one point, the camera panned to the first lady and, according to Brock, Kavanaugh exclaimed, “Bitch!” This response summed up what Hillary Clinton had become to the hard right, and would remain.

When Starr delivered what he called his “referral” to the House, the public shock was profound, largely because of its prurient passages. Why did Starr choose to include, for the benefit of the entire world, the graphic details of Clinton and Lewinsky’s sexual trysts? Starr now claims he had no idea that the House Republicans under Speaker Newt Gingrich would immediately put the document on the Internet, a lame assertion from anyone who lived through the acidulous atmosphere in Washington during that impeachment autumn. Starr also claims that his staff decided that every sexual act had to be described minutely in order to show that, whatever the president’s definitions, he had indeed had sexual relations with “that woman.” But Clinton had earlier testified that he had had inappropriate intimate contact with Lewinsky short of sexual intercourse—a truthful statement that would have sufficed for Starr’s purposes without all the pornography.

At the time, some of the writers and journalists whom I knew around Washington speculated that, by including explicit details in his report, Starr really just wanted to humiliate Bill Clinton, with Lewinsky suffering collateral damage. After reading Contempt, though, it seems much more likely that the person Starr wanted to humiliate wasn’t the president so much as it was the president’s unyielding feminist attorney wife.

-

1

It is unclear whether Starr’s desire to clear his reputation is compounded by his departure from the presidency of Baylor University in 2016 amid a scandal involving official neglect of sexual abuse of women by male athletes. Contempt mentions the matter only in passing as an example of a noble captain going down with his ship. ↩

-

2

The historical amnesia is just as bad among conservative pundits, although in their case it may be more a matter of willful revision. See, for example, Ross Douthat, “What If Ken Starr Was Right?,” The New York Times, November 18, 2017. ↩

-

3

“Nearly a Coup,” The New York Review, April 13, 2000. Apart from my own recollections, my account of the impeachment draws chiefly on the two books under discussion in Lewis’s review: Jeffrey Toobin, A Vast Conspiracy: The Real Story of the Sex Scandal That Nearly Brought Down a President (Random House, 2000); and Joe Conason and Gene Lyons, The Hunting of the President: The Ten-Year Campaign to Destroy Bill and Hillary Clinton (St. Martin’s, 2000). ↩

-

4

See Kenneth W. Starr, “The Integrity of William Barr,” The New York Times, January 16, 2019. ↩

-

5

“Starr is a real Republican, and he’ll give us a real investigation,” the right-wing California congressman Robert Dornan exulted after Fiske’s ouster. Earlier, Dornan and nine colleagues had sent a letter to the Sentelle panel urging it to replace Fiske. See Sara Fritz, “Fiske Ousted in Whitewater Case,” Los Angeles Times, August 6, 1994. ↩

-

6

Details about the work of various conspiracy theorists, including Christopher Ruddy, Reed Irvine, and Hugh Sprunt, and the Office of Independent Counsel’s intensive investigations of their claims appear in Kavanaugh’s attorney work files, which are part of the records of the Office of Independent Counsel housed in the National Archives. See especially the Foster files contained in Boxes 143–145, available online at archives.gov/research/investigations/kavanaugh. ↩

-

7

It took Starr even longer—in his formal report, delivered on the eve of Clinton’s impeachment—for him to reveal that he had nothing negative to say about the Clintons concerning all the other matters he had been investigating for years, including Whitewater. ↩