In October 1876, an intense young man with vague but fervent dreams of becoming an urban missionary went to preach a sermon—his debut in the pulpit—at a Methodist church in Richmond, on the southwestern fringes of London. This foreign drifter, still unsure of his path in life, walked from his nearby lodgings along the River Thames on a day of radiant autumn colors. He adored long contemplative walks, and wrote wonderfully about what he saw and felt on them. In a letter, he captured for his beloved younger brother the river as it “reflected the large chestnut trees with their load of yellow leaves and the clear blue sky, and between the treetops the part of Richmond that lies on the hill, the houses with their red roofs and windows without curtains and green gardens… and below, the grey bridge with tall poplars on either side.” He also transcribed to his brother his homily in church, with its message that “We are pilgrims in the earth and strangers—we come from afar and we are going far.”

Vincent van Gogh had, at that point, made no more art than a few crude sketches. Four more years would pass before the Dutch pastor’s son, who had already tried his hand at picture-dealing, school-teaching, book-selling, and evangelism, would pursue his vocation as an artist. Yet, from his teenage years, he had painted in words, with all the rhapsodic power of a voracious reader steeped in the fiction and poetry of three languages: Dutch, English, and French. The sixty or so surviving letters that Vincent wrote to his brother Theo or, less often, to his anxious parents during the three years he spent in England (from 1873 to 1876) sparkle with scenes that, you feel, only Van Gogh could have honored in paint, from the light of the street-lamps “reflected in the wet street” of a rain-soaked seaside town to the twilit view from a muddy hillside “covered with gnarled elm trees and shrubs” toward “a beautiful little wooden church with a kindly light at the end of that dark road.”

Van Gogh never stopped conjuring in words the landscapes, portraits, and interiors that he had painted or planned to paint. Later letters, especially during his period in Provence after 1888, intersperse striking verbal evocations of trees, skies, fields, faces, even a humble bed or chair, with inset sketches—“croquis,” he called them. They would bloom into many of the best-known, and deeply-cherished, pictures in the canon of Western art. Posterity has adored the image-maker but ignored the writer and thinker behind them. The glamour of those paintings defines the Van Gogh most admirers still know best, the figure recycled most recently by Willem Dafoe in Julian Schnabel’s 2018 movie At Eternity’s Gate.

In contrast, Van Gogh’s spells living in South London, in the Thames-side suburb of Isleworth, and in Kent, at the Channel port of Ramsgate, belong to his prehistory as an artist. With a job secured through family connections, he came to work for the London branch of the leading print-dealers Goupil and Co., and stayed on after the firm fired him, to teach in small schools. Increasingly impassioned in his Christian faith, he then hatched a scheme to occupy “a situation somewhere between minister and missionary, in the suburbs of London among working folk.” We know of only around twenty drawings completed in England—the best of them an earnest but still plodding sketch of the Dutch church at Austin Friars in the City of London, where the would-be evangelist sometimes worshipped.

Young Vincent often felt a failure. He endured loneliness and dejection—though nothing like the bouts of anguish and panic that would seize him in Provence—but he also felt the bittersweet melancholy of a dreamy, wandering outsider. He could go into raptures about autumn days in London, “especially in the streets in the evening, when it’s a bit foggy and the street-lamps are lit,” while fading elm-leaves turn “the colour of bronze.” His letters from England crackle with the descriptive and affective force of what, should he have chosen another fork on that pilgrim road, we would surely now call a born writer. Foggy Victorian London, where literature far outshone in status both the visual arts and music, helped make Van Gogh the artist he became and remained, even when the golden fields and cobalt skies of Provence blazed across his canvases.

“He was a writer before he was a painter,” insisted Carol Jacobi, as crowds flowed around us on the first day of public access to “Van Gogh and Britain,” the exhibition she has curated at the Tate Britain in London, next to the river Vincent loved to walk beside. “‘Writing is like painting’: he says that thirty or forty times,” she reminded me. Through his apprentice years, his writer’s pen obeyed him as his crayon or brush could not. Jacobi, curator for British Art 1850–1915 at the Tate, mentions an 1880 drawing titled Miners in the Snow at Dawn, completed in Belgium, where Van Gogh had gone to live and preach among the poor. It’s an early token of his new-found artistic ambitions. The “word picture” that partners it in a letter is “beautifully accomplished, influenced by Dickens and Zola,” she said. “But he’s struggling to express these things in visual terms.”

Advertisement

In addition to Dutch and French books, Van Gogh admired and re-read English-language authors all his adult life. He loved Shakespeare, whom he would clutch as a lifeline from despair at the St. Rémy asylum in Provence; the novels of George Eliot, whose working-class hero Felix Holt became his model of useful and honorable toil; Harriet Beecher Stowe and, above all, Charles Dickens. “My whole life,” proclaimed a letter from 1882, “is aimed at making the things from everyday life that Dickens describes.”

The exhibition begins with one of those Van Goghs that everybody thinks they know: The Arlésienne, painted in early 1890. This show, though, makes us see that those stark blocks of pale lime that rest on a darker green table in front of the sitter are no mere color-field props but books, and volumes with specific titles, too: Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and Dickens’s Christmas Stories. Across this room at Tate Britain, a bookshelf gathers Victorian editions of scores of the novels, plays, and poetry collections in English that Van Gogh read. Often, the contemporary visual art that appealed to him would lead to the literature that inspired it. An early London letter details his first encounter with John Keats, “a poet who isn’t very well known in Holland, I believe. He’s the favourite of the painters here, and that’s how I came to be reading him.”

His English episodes share the peaks and troughs, the professional missteps, the episodes of bliss, and stretches of gloom, common to countless young worker-travelers in any hectic mega-city, then or now. Van Gogh even fell in utterly unrequited love with his landlady’s daughter, Eugenie Loyer, part of the household at 87 Hackford Road in Stockwell, South London. Today, a blue commemorative plaque adorns the white-fronted building. Down the road stands the Van Gogh Primary School—a memorial in a once largely working-class district the lifelong teacher-preacher would surely have relished. Not far away, venues such as an Italian day nursery and the North Brixton mosque show in brick and stone how the European mobility that filled Queen Victoria’s London with immigrants—temporary or permanent—has both resumed and spread to include incomers from around the globe.

The “pilgrim’s progress” of life that Van Gogh traced in his Richmond sermon brought “strangers in the earth” to the Victorian metropolis from across Europe and (in smaller numbers) from Britain’s colonies in Asia. Over the Thames from Stockwell, Karl Marx lived in Kentish Town and wrote daily at the British Museum in Bloomsbury. Architect of the Risorgimento Giuseppe Mazzini had plotted the liberation of Italy in Soho, Bloomsbury, and Clerkenwell. The Franco–Prussian War and its aftermath carried French artists such as Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, and Camille Pissarro across the Channel either as visitors or residents. British self-confidence at this zenith of empire protected exiled revolutionaries and dissidents against demands for extradition, or even just information, from overseas police forces. Not until the Aliens Act of 1905, prompted by press-driven fears of mass Jewish immigration from the Tsarist empire, would the shutters start to fall.

A conscious “cosmopolitan,” a polyglot, and an inveterate border-crosser, who for almost two decades moved between the Netherlands, France, and Great Britain, Van Gogh lived and breathed the “free movement of people.” (That ideal finally became a pillar of the European Union under the Maastricht Treaty, signed in a Dutch city, in 1992.) Applying to a South London pastor for a position in the church, he pleaded that his “experiences in different countries, of mixing with various people, poor and rich,” as well as his “speaking a number of languages,” should make up for his lack of a seminary education.

He wore this multinational identity with pride—and few visitors will tour the crowded rooms of “Van Gogh and Britain” without sparing a thought for the slow-motion political trainwreck of Brexit. If or when it happens, Brexit will—for Britons and other Europeans alike—bring that hard-won freedom to an official end. Timetabled to begin in the week of the UK’s original scheduled departure from the EU, the exhibition will run through much of the period of limbo that will now follow on, perhaps until October, from Brexit’s latest delay. The turmoil even made an impact on the show’s preparation. The Dutch and UK governments had to assure European lenders that precious works loaned for the show would not be subject to swingeing import taxes if they returned home after a disruptive “no-deal” break with the EU.

Advertisement

Believers in the European project could hardly hope for a more vivid, or timely, demonstration of the benefits that open borders bring. Van Gogh loved the mysterious cityscapes and moody weather of London, finding a “peculiar beauty” in its suburbs. The visionary qualities of the writers, painters, and engravers he discovered in the city helped to guide his eye and brush until his death, in 1890. They aided his pursuit of “a reality more real than reality,” as he’d put it to Theo, that he mastered in the sensual starbursts of his later paintings, such as Starry Night from 1888, with its firework-like explosions of light reflected as golden pillars in the dark waters of the Rhône at Arles. In the show, it sits alongside a Whistler Nocturne of the shadowy Thames. Van Gogh knew and admired Whistler’s Thames-side scenes. In the clear-skied Midi, clarity and outline would replace the swirling murk of polluted London. But even as Van Gogh’s latitudes changed, his attitudes persisted. In turn, successive generations of Van Gogh emulators and acolytes in Britain drew on his breakthroughs in color and form.

Sections of “Van Gogh and Britain” display homages to—or arguments with—Vincent by a dozen British artists, from Walter Sickert to Francis Bacon. In one room, those too-familiar Sunflowers, sold in 1924 to the National Gallery in London by Vincent’s sister-in-law, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, hold court amid a floral host of responses to them by other painters. The quality of these post-Van Gogh works may vary; his commanding presence in them never does. Carol Jacobi refused to employ the stale notion of “influence.” In her view, “It’s much better to think in terms of conversations or retorts.” As Van Gogh’s sunflowers survey this bouquet of tribute acts, I thought of another parallel: the Internet meme that spreads across the web in ever-burgeoning profusion.

Other rooms show how the black-and-white illustrations by British artists in weekly papers (above all, the pioneering Graphic, founded in 1869) left an indelible mark both on Van Gogh’s vision and his method. In the early 1880s, living in The Hague, he built up a personal collection of some 2,000 English prints. Their subject matter—the poor, the homeless, marginal people from England’s lower depths, whether dustmen, street vendors, or war veterans—crystalized his belief in the heroism of everyday life. “He wanted to be a working-man artist,” said Jacobi. In other words, a modest artisan who stood squarely with, rather than above, his figures.

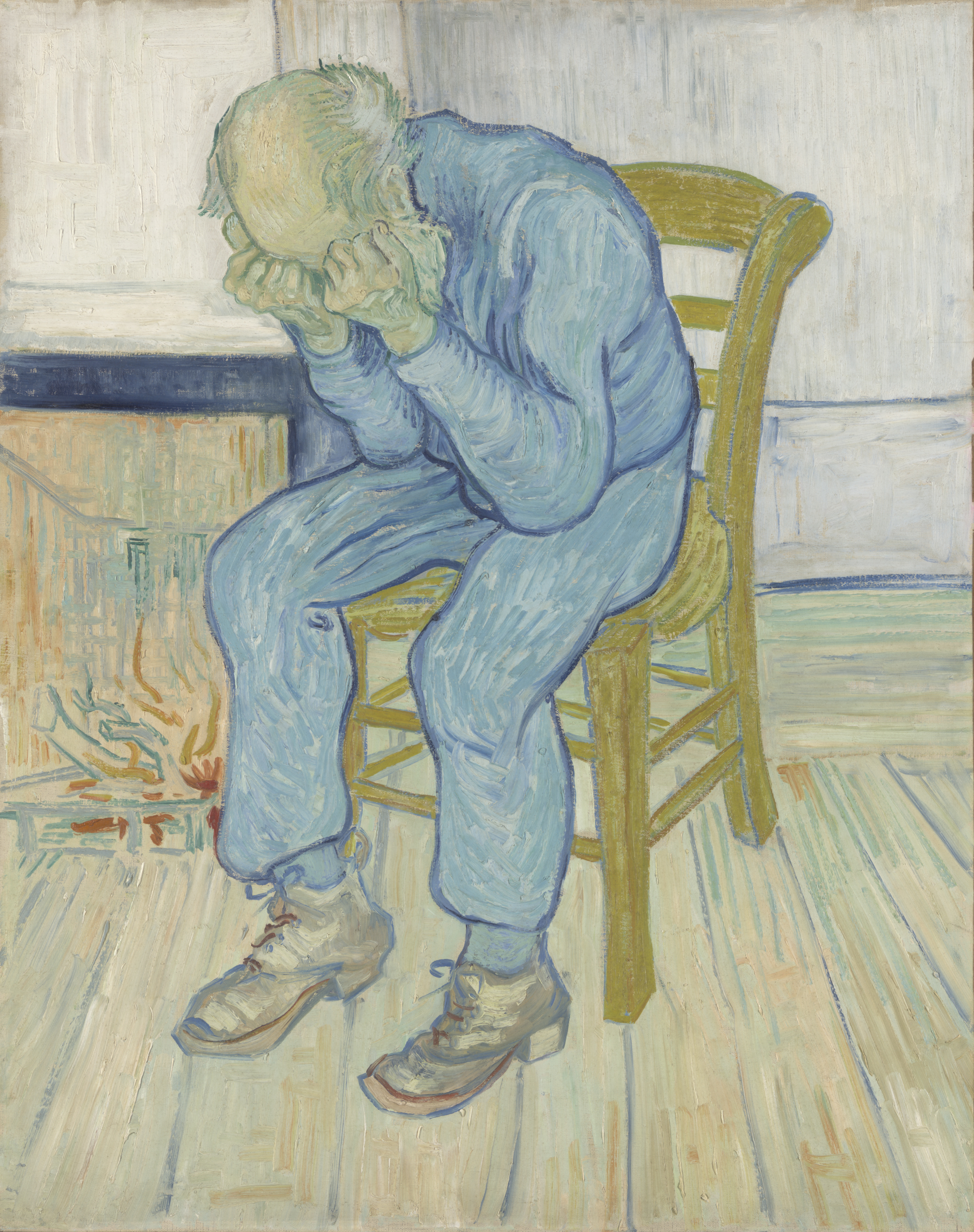

Not only magazine but book illustrations lodged in Van Gogh’s visual memory to resurface in later works. A hunched, seated figure depicted by Charles Reinhart in an edition of Dickens’s Hard Times—one of Van Gogh’s touchstones in fiction—recurs throughout the early 1880s in drawings of similar poses. As “Van Gogh and Britain” demonstrates, it reaches its final form in a painting completed in May 1890, just two months before the artist’s death, in the asylum at St. Rémy. This work, Sorrowing Old Man: ‘At Eternity’s Gate’, seems to condense a lifetime of grief into the blue-clad subject, his eyes hidden by clenched fists, huddled on one of Van Gogh’s yellow chairs—itself so expressive as to seem almost animate, even human.

The artists of the Graphic, chroniclers of the streets rather than the salons, lie behind now iconic images such as Sorrow from 1882, Van Gogh’s stark but tender nude study of his then companion, Sien Hoornik. As for the bold, dynamic strokes that pack tension and action into illustrations from the social-reformer Victorian papers, Van Gogh never abandoned this “English line.” It helped to build up the crow-haunted skies, the wind-scoured wheatfields, the spookily tangled tree-roots, in late paintings of Provence and his final home at Auvers-sur-Oise. Jacobi noted that these “directional scratches,” which inject energy into the documentary prints, create “wonderful force-lines in a picture. And that’s exactly how he uses his brush-strokes.”

Van Gogh’s English years gave him not only a technique but a sensibility: literary, visionary, symbol-haunted, always aware—unlike some of his more formalistic disciples—of the written word as an ally, not an enemy, to the drawn or painted line. To his brother Theo, he affirmed that Shakespeare “and his way of doing things are surely the equal of any brush trembling with fever and emotion.” Occasionally, the Tate visitor will wonder if the suggested links between paintings, prints, or books Van Gogh knew in London and his later pictures may owe more to coincidence than cause-and-effect. Often, however, the show makes firm connections visible: as in the receding avenue of alder trees from a 1689 canvas by the Dutch master Meindert Hobbema that Van Gogh saw, and loved, at the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square. Autumnal avenues, their trees stretching away into an unknown future, would often fill his drawings and letters.

In images or words, they signify the “years of pilgrimage” that began in London and never ceased for him. Wherever he lodged, he continued to be one of those “strangers in the earth” whom he had invoked in that sermon beneath the “friendly daylight” of a bright October day beside the Thames. Only in cherished pictures, and favorite stories, would the wanderer truly feel at home.

“Van Gogh and Britain” is at Tate Britain, London, through August 11.

• All 902 of Van Gogh’s letters, edited by Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakkerfor the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, and the Huygens Institute, can be found at vangoghletters.org.