“All his life, he’d displayed an interest in history and politics. He was disciplined, hardworking, bright, and earnest.” That could be a fitting description of Pete Buttigieg, the thirty-seven-year-old mayor of South Bend, Indiana, who’s currently running for president of the United States.

But it’s not. It instead describes the youthful promise of our thirty-seventh president, Richard Nixon, in a passage from John A. Farrell’s recent award-winning biography.1 Young, upcoming politicians often make such a sparkling impression, which shows the limits of early distinction and hopeful expectations.

That’s not to say that Buttigieg’s Beaver Cleaver visage may be concealing some secret, sweaty Nixonian paranoia. Surely not. The youngest mayor of an American city with a population over 100,000, elected at the age of twenty-nine, and the first openly gay man in the Democratic Party to run for president, he has a genuine charisma that Nixon would have killed for. In interviews and public appearances, including the CNN town hall that introduced him to millions of Americans who couldn’t even pronounce his name (apparently Maltese for “lord of the poultry”), he has been admirably direct, eloquent, and persuasive on what he calls “intergenerational justice.” The first millennial to run for president, he’s referring to the ways in which today’s geriatric politicians are shafting his generation:

If you’re my age or younger, you were in high school when the school shootings became widespread; you’re going to be dealing with climate change…you’re going to be dealing with the consequences of what they’ve done to the debt; you’re on track to be the first generation ever to make less than your parents.

He has been criticized for being vague, and compared to Elizabeth Warren’s highly specific positions, his website is Policy Lite. But he’s saying things progressives want to hear, referring to climate change as “a national security threat,” supporting labor, calling for a slow-walked single-payer health care system, and demanding universal background checks for gun buyers. He’s been deft at issuing sharp Lilliputian jabs to the fatty presidential flank, remarking on Trump’s draft evasion: “I have a pretty dim view of his decision to use his privileged status to fake a disability in order to avoid serving in Vietnam.” He’s released ten years of his tax returns and has a refreshingly modest income for a presidential candidate. His even-tempered candor has led to a jump in the polls and vaulted him into the top tier of candidates, beyond the reach of the less disciplined, if hipper, youngster Beto O’Rourke.

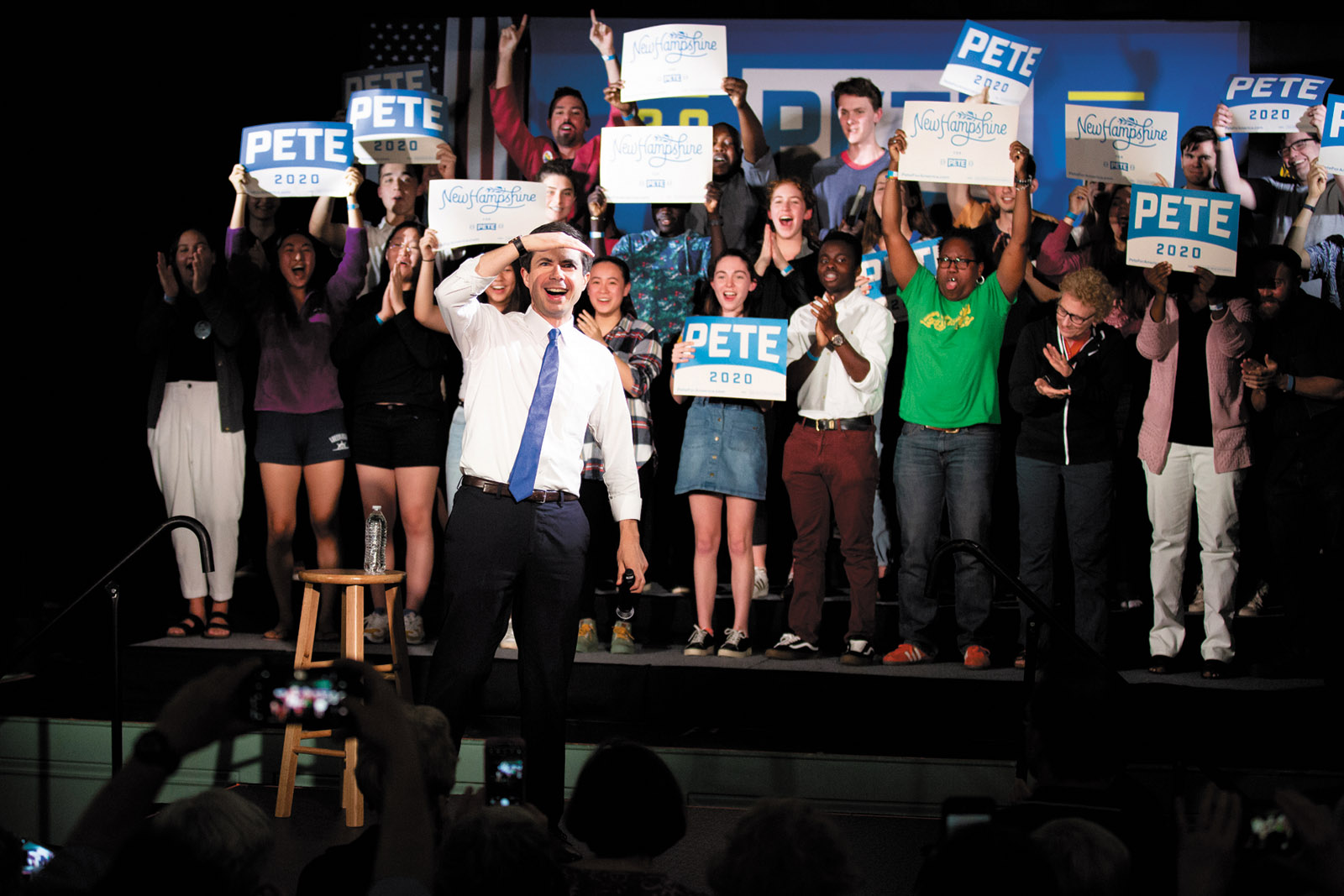

The money has followed. Suddenly flush with cash, with some polls showing Buttigieg in fourth place (after Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, and either Warren or Kamala Harris), his campaign has begun hiring staff. His strong appeal and emergence from a crowded field may be tied to a host of factors, perhaps chiefly his ease and intelligence, youth and likeability, inspiring New York magazine to swoon, “What mother wouldn’t love this guy?”2 (My own, a kindergarten teacher, would have called him “as cute as a bug’s ear.”) Yet his service in Afghanistan lends considerable gravitas. A gay veteran, running for president and embracing his husband onstage, he has demonstrated to many Americans a love and pride that The Boston Globe termed “remarkably unremarkable.” In virtually every televised appearance, he has come across with the kind of natural wit and charm for which John F. Kennedy was once celebrated.

Buttigieg’s campaign memoir, Shortest Way Home: One Mayor’s Challenge and a Model for America’s Future, introduces the candidate by heavily emphasizing his hometown ties. In it, he seems bent on leveraging his midwestern values, giving the strong sense of being almost radically wholesome. He does this by presenting, in an astounding act of compression, a life packed like a Marie Kondo underwear drawer full of neatly folded accomplishments, all achieved with apparent effortlessness.

Our Man in South Bend is nothing if not industrious. He gets himself born to a pair of Notre Dame literature professors in 1982, his mother a Hoosier, his father an immigrant from Malta. He graduates from high school in 2000, winning first prize in the Kennedy Library’s “Profile in Courage” contest, for an essay extolling Bernie Sanders’s commitment to public service, enjoying soft drinks with the Kennedys at the awards ceremony. He attends Harvard, studying Arabic as a freshman, attracted by the “linguistic rhythm and the poetic richness” of the Sudanese novel Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih, letting us know that he rested his head in the room where the adolescent son of Ulysses S. Grant once slept, as did Horatio Alger and Cornel West. He served as student president of Harvard’s Institute of Politics and studied with the great scholar of Puritan America Sacvan Bercovitch. He labors with his professor’s research assistants on The Cambridge History of American Literature, and his senior thesis in History and Literature draws a connection, he says, between uncompromising American exceptionalism, as criticized in Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, and our “government’s narrative about Vietnam.”

Advertisement

Graduating Phi Beta Kappa and magna cum laude in 2004, he volunteers for a summer with the Kerry presidential campaign. A Rhodes Scholar by the following year, he leaves Oxford’s Pembroke College two years later with first-class honors in its Philosophy, Politics, and Economics program. The New Yorker has helpfully filled out the picture by adding colorful details to Pete’s tenure there that he himself chose to skip, reporting that he curated a “whiskey library,” learned Norwegian (one of his eight languages) on the toilet, and sequestered himself in a North Sea cargo ship to study for final exams.

Buttigieg merely gestures at knocking around during this early period: a summer in Tunis, polishing his Arabic; an internship at Chicago’s NBC news affiliate; and a year with the Cohen Group, the consulting outfit of William Cohen, Bill Clinton’s second secretary of defense, organizing a conference of “American and Muslim leaders.” He then joins McKinsey and Company, the enormous international management consulting firm most benignly known for supplying CEOs and reports to an enormous number of corporate entities around the world. In 2009 he joins the US Navy Reserve. The following year he leaves McKinsey, runs for Indiana state treasurer, and loses to Richard Mourdock (who ultimately runs for a US Senate seat arguing that pregnancy caused by rape is “something that God intended to happen”). In largely Republican Indiana, the loss is foreseen but not humiliating. It slows him down not at all. Fired up by a January 2011 Newsweek article listing South Bend among “America’s Dying Cities,” he parlays his new political connections and fresh face into a successful run for mayor.

Thus the middle stretch of the memoir is taken up with governing—adjusting to his role as civic cheerleader and campaigning to revitalize South Bend’s disintegrating neighborhoods. He struggles to diversify the economic base by attracting new “Silicon Prairie” tech companies; introduces a 311 customer service system; sets out to rehab or demolish a thousand abandoned houses in a thousand days (doubling the city’s eviction rate to one of the highest in the country); and launches what he calls “the smartest sewers in the world.” A propagandistic tone creeps in, “tough decisions” set up so we can see the triumphant outcome. But a sour note emerges as well. At one point, a city councilman tries to deflate the Buttigiegian enthusiasm for apps by comparing the mayor to one of the worst technocrats in American history. “Sometimes, Pete,” the councilman told him, “when you talk about your data-driven government, I think of Robert McNamara.” Buttigieg attempts to neutralize this criticism by way of saying that of course he recognizes the value of “qualified, experienced individuals” over statistics, and tries not to forget the quality of “mercy” in bringing “data-driven techniques” to bear. Nonetheless, the comparison lingers.

It is as mayor that Buttigieg, a naval reservist, deploys to Afghanistan in 2014 for seven months, an episode dispatched with astonishing brevity given its importance. His memoir concludes on a romantic note, his time overseas lending urgency to other aspects of life. “If not for the deployment,” he writes, he might never have found his way to his partner. Realizing that life is short, he comes out as gay to his parents and, publicly, to the city, during a reelection campaign, abruptly backtracking in the narrative to hectically acknowledge his unpopular firing of “a beloved African-American police chief” during a scandal over the chief’s alleged violation of federal wiretap law. (His reappointment of the chief was “my first serious mistake as mayor,” he says, arguing that he inherited the problem even while admitting that his handling of it alienated South Bend’s African-American community.)

Unfazed, South Bend reelects him by a wide margin, and he falls in love with Chasten Glezman, a Montessori junior high school teacher of humanities and drama. They marry in 2018 and acquire an adorable rescue dog, named Truman, after the president who said, “If you want a friend in Washington, get a dog.” (They now have two.) He closes out his account having recognized a pattern “visible across all I’d learned in philosophy and literature, business and service, politics and love.” Like Dorothy, after she’s whisked off the prairie by her own version of a Rhodes scholarship and several years in data management, Pete realizes that there’s no place like home.

Advertisement

Buttigieg somehow relates this charmed life with suitable self-effacement, eyes cast modestly downward as in the photograph on the book’s cover, a not unimpressive feat given the perfection of his résumé. Judging by Shortest Way Home, Pete is indeed a paragon, or, to cannibalize his subtitle, “a model for America’s future,” and his memoir has thus inspired Olympian encomiums. The Guardian called it “the best American political autobiography since Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father.”

Not so fast. Political autobiographies, released in droves at the beginning of campaigns, are notoriously vapid and slippery documents, and Buttigieg’s—perhaps more polished than the rest—shows troubling signs of the genre. There are gaps in the record. There’s an avoidance of self-analysis, a refusal to plumb motivations, a tiptoeing across the minefield of human experience. Its wide-eyed ingenuousness strains credulity if only because all credulity, in the age of Trump, is now so strained that it may be collapsing, like the climate, altogether. The self-presentation is too glossy, too ideal. Nowhere does one get the sense that the author has ever experienced a setback or suffering of any kind: depression, humiliation, discrimination, anguish, illness, poverty, doubt, debt. (Buttigieg’s father died in January of this year, after the book had gone to press.) Has he ever been crushed? Could he relate to someone who has been? It seems so: he describes his struggle to overcome shyness and an initially uncertain response, as mayor, to a grieving mother who had lost a child to gun violence. But it’s hard to escape the suspicion that this frictionless memoir represents, beyond the obvious political calculation, an act of self-conscious second-guessing.

By contrast, Obama’s often harrowing reflection on coming to terms with a fractured family history, his honest account of anger and confusion over racial identity and his father’s absence and ultimate loss, elevated it above “the routine political memoir,” as Toni Morrison pointed out on NPR not long after he was elected in 2008. She called it “unique,” and so it remains. The quality of writing and depth of analysis justified the widespread belief, expressed in Time, that Dreams “may be the best-written memoir ever produced by an American politician.”

Buttigieg wants to be in that league, alluding to a love of literature that “captured not just my mind but also my emotions” as early as sixth grade, when he discovered Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” in English class, learning that it was not “about two roads in a forest but about the choices we make in life.” James Joyce’s Ulysses supplies the title of the book and three chapter epigraphs (all available on Goodreads’ list of Ulysses quotes); Hilary Mantel makes a cameo as well. But literature—especially Ulysses—is about exposing the self in all its discomfiting and agitating guises, laying bare its mental gymnastics and unruly, compulsive needs and bodily appetites. There’s not a lot of Joycean revelation going on here.

Instead, Buttigieg often approaches himself with Spock-like detachment, saying little about his sexuality until he comes out at the age of thirty-three to his parents—“they weren’t terribly surprised”—and hears his mother’s wistful disappointment when she asks whether he’s seeing anyone and he says no. Then, he decides, like a Vulcan who has sex once every seven years, “I had to figure out a way to go public, so I could begin adding this dimension to my life.” This “dimension”? He tackles the search for a mate as a technical challenge, trying out online dating apps and scrolling to “pick out the right photos for a profile.” He’s more comfortable in attack mode, detailing the political fallout, in 2015, for Indiana governor Mike Pence after he signed the discriminatory Religious Freedom Restoration Act: “The effect on our economic image was immediate and destructive.” Before the law was walked back days later, amid a national outcry, Buttigieg’s office distributed stickers reading, “COME ON IN: SOUTH BEND IS AN OPEN CITY.”

Ultimately, though, Buttigieg is at his best when he finds himself in love and describes his relationship with Chasten and their life together. His empathy for Chasten’s struggles during a period of homelessness after coming out to his parents at seventeen is sincerely moving, and he may reach fair-minded socially conservative readers with his calm, commonsense depiction of the trials of people who simply want to exercise the rights that belong to them:

Perhaps it is the fear of any queer person preparing to come out that he or she will be marked as a kind of other, isolated from the straight world by virtue of being different. No doubt many have that kind of experience—indeed all do, at least a little bit. But the main consequence for me of coming out, and especially of finding Chasten, is that I have felt more common ground than ever before with the personal lives of other, mostly straight, people.

Before, I could rarely relate to the stories I heard from others when it came to adult domestic life or romance. Today, being in a committed relationship with Chasten just might be the most normal thing about my life…. For this reason most of all, it is mystifying that some persist in describing sexual orientation as a “lifestyle.” In those fragments of our days that aren’t dominated by work, our lifestyle revolves around meals, friends, exercise, housekeeping, sleep, extended family, and the care and feeding of our dog. Trying to visualize it from the outside, it strikes me that my partnered, gay “lifestyle” is a lot more normal, sustainable, and fulfilling than my prior lifestyle consisting almost entirely of work and travel.

What is concerning, however, is his glossing over important elements of the unimpeachable résumé. He takes pains to make his McKinsey years seem dull, an uninspiring slog through spreadsheets and “Canadian grocery pricing.” Joining “the Firm,” he wants us to know, was purely for an “education in the real world” of business; he wanted to learn “how the private sector really worked.” This is doubtless meant to distract us from the company’s notorious reputation (and perhaps also from what he was doing as a McKinsey consultant in Afghanistan, something he mentions but never fully explains). The Massachusetts attorney general recently revealed that McKinsey had urged the pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma to “turbocharge” opioid sales, and The New York Times reported that it has “helped raise the stature of authoritarian governments” in Ukraine, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, South Africa, and China.

But McKinsey’s elastic ethics are not just an issue now. They stretch back to the time when Buttigieg worked there and long before. Said to have been “the firm that built the house of Enron” (Jeff Skilling, Enron’s CEO, worked for McKinsey for twenty-one years), it famously promoted “creative destruction,” advising companies to “identify your bottom 10 or 25 or 33 percent, and get rid of them as soon as possible,” according to The Firm, a history of McKinsey by Duff McDonald. At the same time, McDonald writes, it urged corporations and their boards to raise executive compensation to obscenely high levels. While Buttigieg worked there, his employer also encouraged “the securitisation of mortgage assets,” in the words of the financial reporter Ben Chu, contributing to the economic crisis of 2007. In 2012 its longtime managing director was convicted of insider trading.

Choosing McKinsey right out of the gate may have been Buttigieg’s first stumble, and his responses to questions about it since have compounded the problem. Asked recently about the company’s part in the opioid crisis, Buttigieg punted, saying, “That I didn’t follow.” Asked about its support of authoritarian regimes, he said, “I think you have a lot of smart, well-intentioned people who sometimes view the world in a very innocent way. I wrote my thesis on Graham Greene, who said that innocence is like a dumb leper that has lost his bell, wandering the world, meaning no harm.” At this point in his career, it’s time for him to stop talking about his Harvard thesis and start talking about the horrific consequences of American “consultants” operating abroad, unchecked, from Vietnam to Iraq. Otherwise, the dumb leper in this story might as well be named Pete.

Even Buttigieg’s account of his experience in Afghanistan feels evasive, perhaps because, having worked in counterterrorism (just like Greene’s own quiet American), he can’t describe aspects of his service beyond saying that it involved “blocking the flow of narcotics funding to the insurgency.” But he could explain his own motivation for signing on in the first place. As a Harvard student, he opposed the invasion of Iraq, delivering a speech on behalf of the College Democrats at an antiwar rally, speaking of “the difference between necessary wars…and unnecessary wars that could take young lives for no purpose at all.” Six years later, in September 2009, he enlisted in the Navy Reserve.

What led him to the road taken? Here the language gets murky. He alludes vaguely to the guilt that arises as he and a few friends, in their mid-twenties and volunteering for the Obama campaign in Iowa in 2008, realize that a lot of their cohort, or at least the ones who didn’t go to Harvard, were serving in the military. Knocking on rural doors, he finds that “every other teenager I met was signing up for the Army or the Guard.” At the same time, he recalls that “one of my heroes,” a great-uncle who served as an army airman, died in a plane crash in Ohio in early 1941.3 A portrait of the captain once hung on his grandmother’s wall; it now hangs on his.

But he does not explain clearly whether he joined out of obligation or an eagerness to serve his country. And why the Navy Reserve? While his stint as an intelligence analyst (with a “top-secret clearance”) does justify the feeling that Buttigieg’s résumé qualifies him better for a career as a spook than for one as a politician, he offers no explanation for how he determined that the war in Afghanistan was “necessary,” an account essential for evaluating this candidate’s approach to future conflicts. All he offers is this passive, negative construction: “The more I reflected on it, the less it seemed I had any good excuse or reason not to serve.” If he joined because there was no reason not to, there’s nothing wrong with a sense of duty. But there is something wrong with being unable to articulate the nature of your commitment, especially when you’re running for president.

His writing gets more convoluted as he describes his deployment, which occurred five years after he signed up, during Obama’s 2014 drawdown, the concluding months of “Operation Enduring Freedom.” He grapples with the realization that the big show is folding its tent and that he’s part of a packing-up effort, realizing that if he were to push too hard, he would be “risking my life and others’ to keep going outside the confines of the base.” He wants us to know that “the mission…still mattered,” but he doesn’t say why. Instead, he becomes fixated on the belatedness of his service, recalling John Kerry’s 1971 testimony before Congress, when the Vietnam vet famously asked the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?” Buttigieg quickly says, without elaborating, “I did not believe the Afghanistan War was a mistake.” Imagine the political fallout if he’d asserted that it was.

But he can’t stop picking at the scab, considering soldiers killed in the waning hours of World War I before news of the Armistice reached the front, as well as the famous “Japanese WWII holdouts.” Having brought up every possible permutation of the last-man-to-fall phenomenon, he wonders, “If you manage to get killed in a war that’s ‘over,’ what does that make you?” He doesn’t seem to recognize the irony of the obsession: his great-uncle, as he’s told us earlier, was killed in service to a war that hadn’t yet begun, at least for this country. What did that make him? Is Buttigieg concerned about being less of a hero? Or is he simply unable to explain to himself, and others, what he was doing there?

Mortality surely occupies the thoughts of anyone in a war zone, and Buttigieg’s service did involve mortal hazards every time he left the base in Kabul as a driver. He describes those he knew who were killed in the waning days of the operation, ruminating over the “brutal luck” of one soldier walking away while another gets killed, something that “compounds the cruelty of loss by allocating it for no clear reason at all.” But for himself, he can’t seem to resolve the psychological quandary born, perhaps, of conflicted feelings. Just as he never adequately examines his reasons for joining, he can’t seem to account for the emotional and moral consequences of having done so. His reflections about “the dictatorship of chance” only emphasize that he can’t clarify what it was that made the mission matter.

The most revealing anecdote Pete Buttigieg has told about himself occurs not in Shortest Way Home but in the New York magazine profile. The reporter, Olivia Nuzzi, catches him before he can massage his memory into acceptable banality:

When I asked him if he was drawn to politics early on, the type of child who was president for Halloween, he said, “I think I actually did dress up as a politician once on Halloween.” He tried to move on, talking about his boyhood dream of being a pilot. But wait—which politician was it, I asked? “It was just a politician in general,” he said. “I remember I made, like, a little—for whatever reason, I noticed the little microphones, the little mics that politicians wear, and I, like, made a little one of those out of paper and clipped it to myself and wore a little suit.”

It’s easy to see Pete in that little suit, with his tiny paper mic; it’s practically the cover of his book. But there’s a sad, Pinocchio-like quality to him in this costume. Can he become a real boy? A real politician? First he must prove himself brave, truthful, and unselfish. With this memoir, in which our hero emerges from a bedtime story of a book freshly carved and polished for his political future, he may be halfway there.

-

1

Richard Nixon: The Life (Doubleday, 2017). ↩

-

2

“Wonder Boy,” New York, April 14, 2019. ↩

-

3

The crash occurred in the US, near Athens, Ohio, a fact Buttigieg does not include, but details are readily available. See “Craft Comes to Rest Near Huge Oil Tank,” News-Journal, Mansfield, Ohio, February 22, 1941. Bound for Wilbur Wright Field, the plane was piloted by Captain Lawrence J. Eyler; Captain Russell Montgomery, Buttigieg’s maternal grandmother’s brother, was a passenger. It went down when a wing clipped trees, and the resulting fire was so hot that aluminum melted. The bodies were burned beyond recognition, making it unlikely that Montgomery’s log, from which Buttigieg quotes a representative passage, was found with the remains, as the family had thought. ↩