Ever since Giorgio Vasari wrote Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects in the sixteenth century, we in the Western world have understood artworks and biographies as intertwined. This isn’t inevitable. A glance sideways geographically, or over the shoulder historically, shows that most cultures have not much cared how someone was feeling when an artist sat down to carve a particular idol or paint a certain krater. We, on the other hand, are so accustomed to using the art to illuminate the life, and the life to interpret the art, that when faced with a skeletal CV and a great painter—Johannes Vermeer, perhaps—we fill in the gaps with novels and biopics.

Self-portraits present particularly attractive targets for this approach. They allow us to put a face to a name, and (we fancy) a personality to the face. “The Self-Portrait: From Schiele to Beckmann” at New York’s Neue Galerie was one of several ambitious exhibitions on the genre to be organized this year.1 Its specific purview—German-speaking Europe in the first half of the twentieth century—encompassed dozens of important painters against a background of overarching historical calamity. Such pictures have the capacity to make monumental tragedy both personal and complex. But to have taken these sixty-plus pictures at Facebook value, as autobiographical documents tagged on a timeline, was to have missed what is most captivating about the self-portrait as a form: in no other mode of art is the mechanism of representation—the looking and the lying—laid so bare.

The show’s opening artist, Egon Schiele, is a good example of this. Schiele has come down to us as the poster boy for overwrought Viennese subjectivity. In a career lasting barely a decade (he died in the flu epidemic of 1918, at the age of twenty-eight), Schiele made himself the subject of some thirty-two paintings and two hundred works on paper, by the tally of Tobias G. Natter, the exhibition’s curator. In the fine group of drawings on view, we saw Schiele as a brooding roué, a twisted totem, a martyred Saint Sebastian, and what now looks like a cocky member of a boy band. In one, he figures himself as a triad—one third fidgety, one third haughty, one third blasé. This shape-shifting, along with his habitual gothic hands, gaunt torso, and bruised flushes of color, has been seen as a marker of intrepid psychological exposure, and fed a certain modernist ideal of the self-portrait: a picture that shows not just the face but the soul. (Neue Galerie founder Ronald S. Lauder writes that the first self-portrait he ever bought was a Schiele, around 1964.)

But there is also something jejune about Schiele’s personae. The preening and martyrdom can seem a bit adolescent. And while his genius as a draftsman is never in doubt, neither is his consciousness of it—his line stretches, crumples, leaps, and rolls like a parkour champion. One can imagine that at the end of a day spent drawing himself scourged and naked, he would have given a little thumbs-up and decamped happily to his corner Beisl for a quick schnapps. Indeed, Natter notes that “Schiele’s disturbing poses do not at all coincide with the way he was described by his contemporaries…he appears to have struck them as calm, relaxed, and agreeable.” Photographs of the artist affirm this perception. So, in which of these is he playacting—the drawing or real life? Perhaps to Schiele, the gap between the self on paper and the self in the world was obvious evidence of imaginative invention now lost on audiences who never knew the man.

At the Neue Galerie, Schiele was hung alongside a handful of pre-twentieth-century works intended to establish the foundations of the discipline, including a short run of Rembrandt etchings. These tiny, charismatic prints offer an alternate way to think about Schiele and much of the art that follows: Rembrandt, donning various caps and attitudes, was both a careful student of his own face and of the Dutch tradition of the tronie, a typological character portrait. Each image is, at one and the same time, really Rembrandt, and Rembrandt playing a part.

The show’s most eccentric inclusion was hung nearby: a seventeenth-century copy of Albrecht Dürer’s 1508 Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand Christians. Dürer is widely acknowledged as the first serial self-portraitist, and his transcendent self-portrait of 1500, with its overt nod to Salvator Mundi images of Christ, set a standard for explosive talent and prodigious ego that has rarely been superseded. But the Martyrdom painting is quite a different thing—a gory and jam-packed mise en scène through which pint-sized versions of the painter and his friend Conrad Celtis stroll like flaneurs on the Boulevard Saint-Germain (behind Celtis’s gesturing hand a dog laps at a puddle of human blood). The itty-bitty Dürer looks straight at us and identifies himself with a sign on a stick, but it is hard to square this composition with any notion of interior psychological revelation.

Advertisement

For all its romantic appeal, the idea of the self-portrait as a kind of X-ray of the soul suggests a certain naiveté about what artists actually do. A painting or drawing is not a snapshot—it doesn’t capture a single moment, either interior or exterior. It is a construction, strategized and artificial, that may dissemble or disclose.2 Mostly, like people, self-portraits do both, and the balance can tell us something about the person and the pressures of the time.

Despite Schiele’s headline billing, the narrative arc of the Neue Galerie show began slightly earlier, with two captivating paintings by Paula Modersohn-Becker, Self-Portrait on Her Sixth Wedding Anniversary (1906) and Self-Portrait with Two Flowers in Her Raised Left Hand (1907). In the Anniversary picture, she wears nothing but an amber necklace above her hips and extends her stomach as if pregnant (the pose is reminiscent of Saint Catherine in Jan van Eyck’s Dresden Triptych, though Saint Catherine keeps her clothes on). As a nude self-portrait by a woman, the picture is almost unprecedented, but her attitude is one of contemplative curiosity, not bravado. It’s the expression people wear when trying on clothes—not how do I feel, but how does this look?

By the time she painted Two Flowers, Modersohn-Becker was actually pregnant, a fact discernable by the way her left hand rests horizontally across her abdomen, just above the bottom edge of the canvas. Having studied and worked in Paris off and on for several years, she had absorbed not only a certain Nabi-like reductionist aesthetic but also Cézanne’s sensitivity to the tension between internal volumes and external surfaces. For an artist of her sensibilities, pregnancy must have been (among other things) a state of formal fascination. After all, at no other time of life does the relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic feel more viscerally weird. But Two Flowers is no more a painting about pregnancy than Anniversary is a painting about nudity. Both are paintings about painting. Their profundity arises from the artist’s decision to pose her questions through the subject matter of her own body.

Modersohn-Becker died young, in 1907, the result of a postpartum embolism a few months after Two Flowers was painted. She never experienced the political, economic, and philosophical free fall that began in 1914. Perhaps this is why her paintings seem so distinct from the rest of the show—on no other face do we see that look of unguarded curiosity.

The Expressionist artists who followed—represented in the exhibition most notably by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Oskar Kokoschka—worked to develop a public language for private emotions. A poster on view showed Kokoschka picking up the theme of martyrdom, depicting himself with a shaved head and pointing to a wound in his side. Also on view was a work from a decade later, in which he is seen, hirsute and whole, in the process of painting that earlier raw image, now a citation.

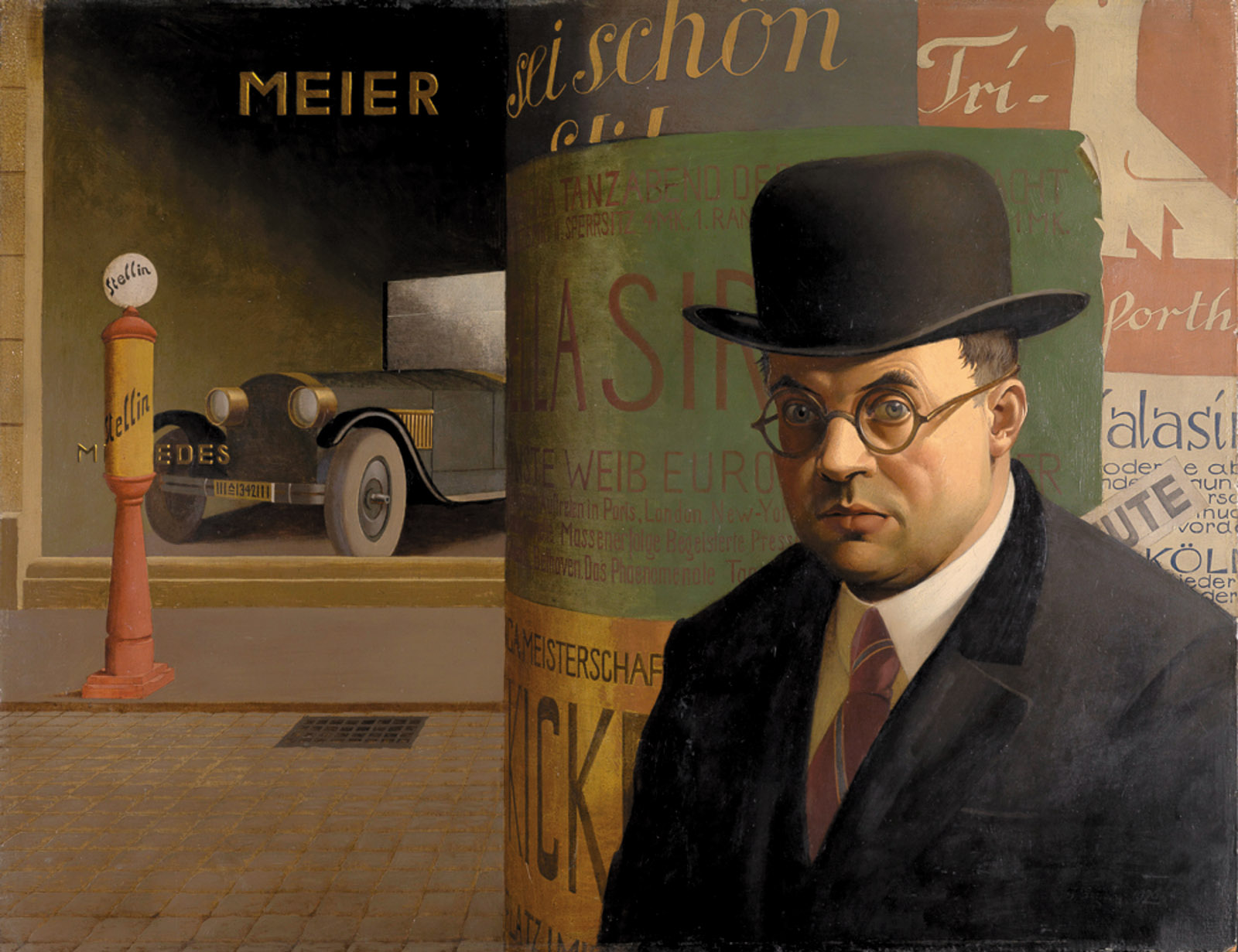

The bloody squalor of World War I and the subsequent ruinous peace shifted the balance again. Artists working in the twitchy 1920s and 1930s had survived one catastrophe that no one saw coming; now their eyes were wide open to social and material realities. A 1925 exhibition at the Kunsthalle Mannheim put a name to this new attentiveness, Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). Across a range of personal styles, from rugged and brushy to commercially slick, artists pictured themselves as part of a societal structure signaled by things and places. One of the pleasures of the Neue Galerie show was the presence of a number of artists seldom seen on this side of the Atlantic. There was a gem of a watercolor by Grethe Jürgens, small and taut with concentration. Large, ambitious canvases by Herbert Ploberger, Wilhelm Heise, and Georg Scholz teemed with objects rendered with didactic clarity and arrayed in a manner as unnatural and suggestively symbolic as Dürer’s Melancholia.

Scholz’s painting, which shows the artist bespectacled and bowler-hatted on a city street, anchored a long wall of worried men, including Otto Dix, Rudolf Wacker, and Lovis Corinth, all standing in three-quarter view, all but Scholz at their easels, most in jacket and tie. Through narrowed eyes under cinched brows, they look at us (which is to say, themselves, in the mirrors we can’t see), but in the show they also looked at one another: Wacker flips Dix’s composition left-to-right; Dix arranges his left hand in a way that recalls not just Schiele but Dürer and Christ. The cigarette that dangles from Wacker’s hand, even as he holds a maulstick (which can’t be easy to pull off), is a cousin to those flourished by Max Beckmann in paintings as far back as 1907 and by Edvard Munch two decades before that. As much as each self-portrait is an assertion of individual identity, it is also a catalog of appropriations and allegiances.

Advertisement

The clever hanging of the show made the most of such echoes and interrelationships—pairing, for example, Kirchner’s Berlin Street Scene (1913–1914) with Anton Räderscheidt’s Self-Portrait in Industrial Landscape (1923). It was a bit of a cheat with regard to the exhibition rubric—neither painting shows the artist; rather both depict urban facelessness, one in a style jagged and jarring, the other numbly robotic—but as crowd scenes they did serve to break up the succession of solo heads and standing figures. The decision to label the two main rooms “Expressionism” and “New Objectivity,” however, added unnecessary confusion. Räderscheidt and Kirchner were hung together in “Expressionism,” though Räderscheidt was prominently associated with Neue Sachlichkeit. A second Kirchner was hung in “New Objectivity” along with a Lyonel Feininger painted ten years before the term was coined. And how to align Expressionism with Ferdinand Hodler’s self-portraits, accurately described in the catalog as “betray[ing] nothing of himself”? Given that many artists, including Beckmann, had feet in both camps, the imposition of such a binary division seemed counterproductive.

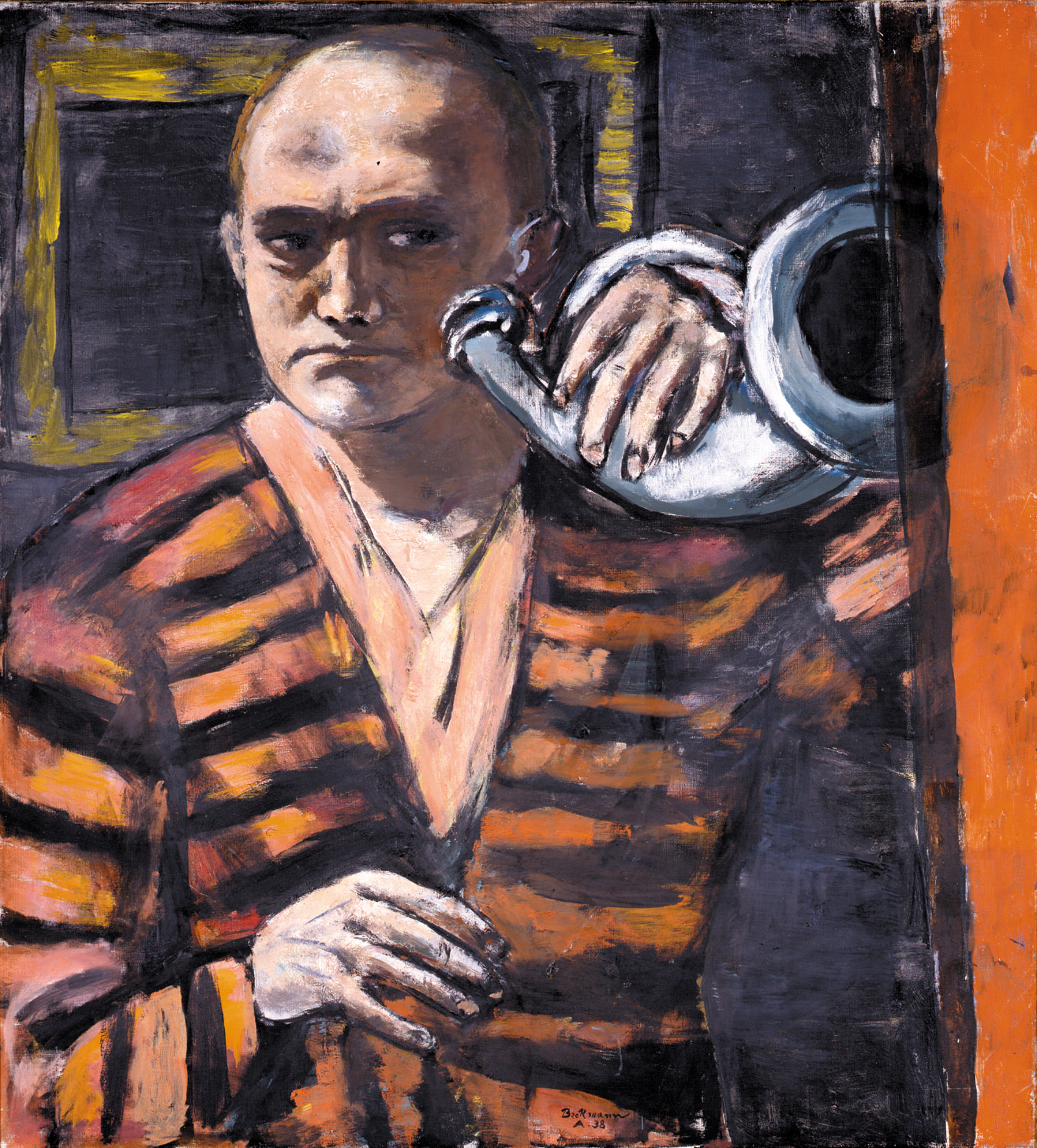

By the time we reached Beckmann’s blunt line and unyielding paint, however, it felt a world away from the jangly solipsism of Schiele. Though he wrote of seeking “true self, of which we are but a pale reflection,” in his paintings Beckmann takes on role after role: he changes costumes (bandages, tuxedo, suit jacket, bathrobe) and handles props (cigarettes, cigars, horns); in Self-Portrait in Front of Red Curtain (1923), he seems to stand on a stage. Walls and furnishings lean in to hold the artist tightly in their grasp, though whether that constitutes security or imprisonment is anyone’s guess: the square head with its set mouth remains somberly impassive. In his catalog essay, Uwe M. Schneede quotes the critic Carl Einstein’s description of Beckmann: “For all his robustness he is a delicate fellow. Thoroughly decent, tortured, very German.” In the mesmerizing 1938 Self-Portrait with Horn Beckmann glances suspiciously at a hunting horn. It is a powerful image of powerlessness, intimating a futile search for omens, or the inevitability of missing the point.

In the 1945 novel The Pursuit of Love, Nancy Mitford’s narrator notes that “when women look at themselves in every reflection, and take furtive peeps into their hand looking-glasses, it is hardly ever, as is generally supposed, from vanity, but much more often from a feeling that all is not quite as it should be.” Substitute men for women and you had the tenor of the New Objectivity room precisely. But why was it all men? The show’s five works by women (Modersohn-Becker, Jürgens, and Käthe Kollwitz) were all hung together in the “Expressionism” room for reasons mysterious.3 In any case, this seems an unduly small number given the many recent European exhibitions highlighting women artists from this period.4 The lack of any mention, even in the catalog, of Charlotte Salomon, whose Life? or Theater? redrew the parameters of autobiographical visual art, was a missed opportunity.5

Men, however, it was: men who have the look of having been taken down a peg, men whose reality no longer aligns with their expectations, men who have been damaged. And they were: Wacker spent five years in Siberia as a prisoner of war; Dix’s experiences in the trenches were relived in much of his later, traumatic art; Beckmann was invalided out after a breakdown; and Corinth, who had once portrayed himself—seemingly without irony—as a knight in armor, was suffering the effects of a stroke that had nearly ended his career. Indeed, all was not quite as it should have been.

Though it was not yet as bad as it would be. Just three paintings in the exhibition were made in the 1940s, all by the German-Jewish artist Felix Nussbaum. They were painted in Belgium, between his escape from a French internment camp (where he had been sent for being German) and his murder at Auschwitz in 1944. The desolate landscape with its distant defecating figure in Self-Portrait in the Camp (1940) has a Surrealist tinge—part Yves Tanguy, part Hieronymus Bosch—with the critical distinction that, while the picture may have been invented, the situation was not. Self-Portrait with Jewish Identity Card (circa 1943) is a shattering riposte to the artful accessorizing of the surrounding pictures: the coat Nussbaum wears, with its mandatory star of David, is not a costume he can slip in and out of. Nussbaum records this bleak reality, but even as he does so he toys with what it means to make a picture: the painted card in his hand bears a painted photograph, showing the artist in the same position and wearing the same hat as in the main body of the painting. It sets up a representational ricochet; neither is the real self.

Why do people make self-portraits? Certainly the expanding understanding of the human mind at the turn of the twentieth century presented artists with an exciting, uncharted domain of “self,” largely unconscious and rife with atavistic urges. But self-portraits can serve myriad purposes: they may be advertisements of skill (Dürer holding his sign) or claims for social standing (one of the many miracles performed by Velázquez’s Las Meninas). Most often, they are products of pragmatism: the artist’s body offers a cheap and available model—a constant against which any number of variables can be tested. Finally, of course, there is the urge to leave a record of one’s existence: I made this. I was here.

In the century of the selfie stick, when self-depiction has become a nearly automatic reflex, a show like this is salutary. It focuses our attention on a mode of self-presentation whose requirements—skill, effort, and the strategic deployment of mirrors—result in images that play out slowly. Time spent in front of them unfolds, in many cases, into something eerily like a social connection. This is true, I think, not in spite of their manipulations, quotations, and obfuscations, but because of them. Human society, after all, isn’t built on bald statements of fact and unfiltered emotion, but on rules understood, inverted, and tactically broken. Perhaps we recognize each other best through the games we play.

-

1

Others include “Eye to I: Self-Portraits from 1900 to Today” at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.; “Visions of the Self: Rembrandt and Now” at the Gagosian Gallery in London; and “Lucian Freud: The Self-Portraits,” opening in the fall at the Royal Academy. ↩

-

2

In her valuable catalog essay, “Self-Depiction in the Shadow of the Camera,” Monika Faber makes it clear that the same was true of self-portrait photographs. ↩

-

3

A Hannah Höch double-exposure was also listed in the catalog as part of the exhibition’s small selection of photographs but did not appear on the final checklist in the press materials, and only two of the three works by Kollwitz included in the catalog were on the checklist. ↩

-

4

Among these: “Die Neue Frau?: Malerinnen und Grafikerinnen der Neuen Sachlichkeit” (Städtische Galerie Bietigheim-Bissingen, 2015); “Künstlerinnen der Moderne: Magda Langenstraß-Uhlig und Ihre Zeit” (Potsdam Museum, 2015–2016); “Jeanne Mammen: the Observer: Retrospective 1910–1975” (Berlinische Galerie, 2017–2018); “Soulmates: Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin” (Lenbachhaus, 2019–2020); “Lotte Laserstein” (Berlinische Galerie, 2019); and a Gabriele Münter traveling exhibition (Lenbachhaus, 2017–2018; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, 2018; Museum Ludwig, 2018–2019). ↩

-

5

See the review by Lisa Appignanesi in these pages, February 22, 2018. ↩