The Spanish poet and novelist Agustín Fernández Mallo’s Nocilla Trilogy had its origins, the reader is informed in a note appended to Nocilla Dream (the first in the series), in the confluence of three seemingly unconnected trouvailles. The first was an article by Charlie LeDuff in The New York Times on May 18, 2004, about “the loneliest road in America,” US 50, which runs through the Nevada desert from Ely to Carson City. “There is a whorehouse, at each end,” LeDuff reports in his article, “and not much company in between.” But in a stand of cottonwoods along the highway outside Middlegate, 110 miles east of Carson City, is a tree that bears the most peculiar of fruits: its branches are draped with hundreds of items of footwear, ranging from work boots to snorkeling flippers.

The first pair of shoes deposited in its branches, LeDuff learns from a Middlegate bar owner, was hurled there in anger some twenty years earlier in the course of a quarrel between a honeymooning couple who had just gotten married in Reno. Their row erupted, as they set up camp beneath the tree, because she had lost a chunk of their savings playing the slot machines the night before, and when, fed up with his complaints, she threatened to walk back to Utah, he threw her shoes into the tree, told her to make her journey barefoot, and drove off to Middlegate to nurse his grievances over a beer. On his return several hours later, they patched things up, and he contributed a pair of his own shoes to what would become known as the Shoe Tree. A year later they were back with their baby, and a pair of the infant’s booties were added as well.

The second trouvaille was Mallo’s discovery on a sugar packet in a Chinese restaurant of two lines from W.B. Yeats’s “Easter 1916”: “All changed, changed utterly:/A terrible beauty is born.” And the third was that on that same day Mallo happened to hear a 1982 song by the Spanish punk rock group Siniestro Total (Total Write-Off) called “Nocilla, qué Merendilla!” (“Nutella, What a Great Snack!”). This song lasts only ninety-five seconds and consists principally of a Johnny Rotten–style rendition of its title, presumably taken from some Nocilla marketing campaign, over thrashing guitars and drums.

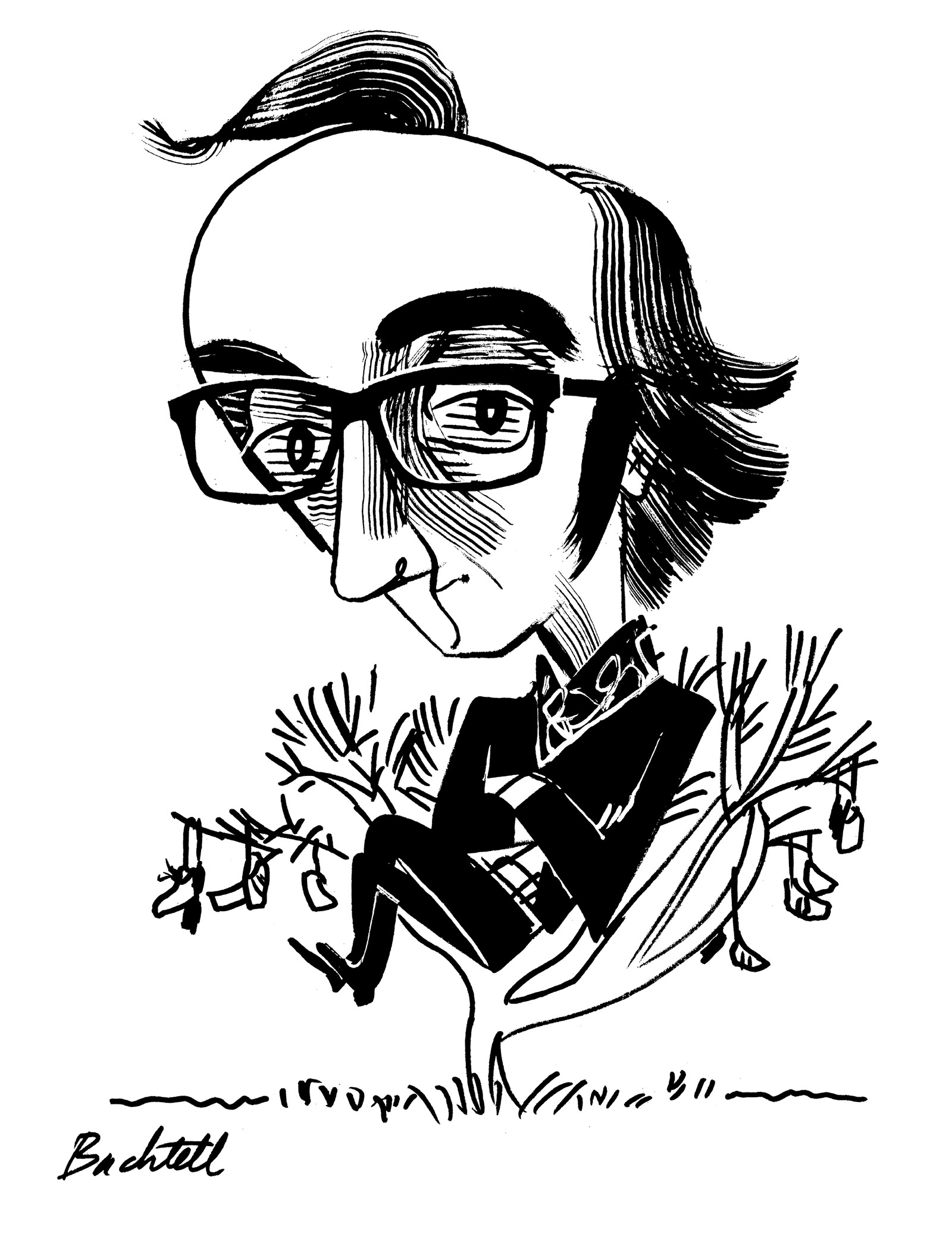

The links between the article, the Yeats quote, and the Siniestro Total song are not developed further, nor do they need to be: for Mallo is here advertising his openness to contingency; all that matters is his willingness to allow the “collective fiction” of “reality” (to use his terms and scare quotes) to merge and mingle with his own “personal fiction” to create the “docu-fiction” that is the Nocilla Project. This project resulted not only in the three novels of The Nocilla Trilogy (published to great acclaim in Spain between 2006 and 2009) but also in a video version available on the website El hombre que salió de la tarta. Part documentary, part manifesto, this hour-long film combines interviews with admirers of Mallo’s writing with sequences that on occasion transpose passages or images from the novels; it concludes, fittingly, with footage of Mallo hurling his own orange sneakers into the Shoe Tree.

The juxtaposition of random elements and the dispassionate intermingling of high and low, or elite and commercial, cultures have long been standard features of post-modernism’s take on our crazy world, and Mallo’s trilogy fits fairly comfortably alongside the work of the many writers and artists and filmmakers that these novels either mention or evoke: Jorge Luis Borges, Julio Cortázar, Octavio Paz, Italo Calvino, Thomas Bernhard, Georges Perec, Paul Auster, Michel Houellebecq, Jim Jarmusch, Takeshi Kitano, Wim Wenders, Guy Debord, Robert Smithson, Damien Hirst, Henry Darger, Antonin Artaud, and Enrique Vila-Matas, to name a few in Mallo’s all-male pantheon (though a fictional woman artist called Margaret does get a walk-on role in Dream). Mallo goes further, however, than all of them in the extent to which he is willing to see his fiction as a collage, a literary version of Internet surfing or channel-hopping—while studiously avoiding any attempt in the manner of, say, W.G. Sebald (another of Mallo’s favorite writers) to orchestrate his borrowings into a coherent expression of his own consciousness or views on history.

Far from protesting against the disparate, absurdist, or inauthentic aspects of contemporary “reality,” Mallo is open about his quest for a literary medium that is itself “simultaneously sludgy and neutral,” and a form, which he terms a “novel-artifact,” that resembles Coca-Cola or Nocilla/Nutella in being a manufactured compound of different ingredients that bear no natural relationship to one another. The LeDuff article, the Yeats quote, and the Siniestro Total song can be connected only by the fact that they happened to engage Mallo’s attention, for whatever reasons, at the moment he came across them. The same is true of the numerous extracts he includes from scientific and mathematical treatises, from interviews with rock stars such as Thom Yorke of Radiohead or Björk, from Martin Sheen’s opening monologue in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (“Saigon…shit; I’m still only in Saigon…Every time I think I’m gonna wake up back in the jungle,” sampled over and over again), or from Greil Marcus’s writing on the Sex Pistols and the Situationists.

Advertisement

Particularly in Nocilla Lab, the last of the trilogy, we are treated to a series of meta-literary riffs that articulate Mallo’s ideal of a “post-poetic poetry,” which, as in some Zen paradox, involves pursuing “method without a method”: the “novel-artifact” that we are reading, he tells us, was “created via the mixing together and overlaying of bodies, of texts, of skins, songs, magazines, of film theory, of bodies that were unalike and yet fit together, all of it speaking, deep down, of jars of Nocilla.” This is from a sixty-page section entitled “Automatic Search Engine,” in which Mallo both recounts how he came up with the idea of the Nocilla Project and outlines the aesthetic assumptions—that is, his “fit[ting] together” of the “unalike”—that the project seeks to enact. Apart from a couple of paragraphs incorporated from a speech Mallo delivered at a book launch, this section is made up of an endlessly ramifying single sentence.

The trilogy opens, however, with the Shoe Tree out on US Route 50 and a former boxer named Falconetti from San Francisco walking the road from west to east, in oblique homage to Christopher Columbus (reversing his east-to-west voyage of 1492).

Like most of the characters thrown up by Mallo’s project, Falconetti’s quest and motivations have a baffling, indie-movie quality. Dream consists of 113 short sections that offer vignettes from the eccentric lives of any number of unlikely characters: Kenny, for instance, on the run from the authorities, lives permanently in Singapore Airport, where he meets Josep, one of the world’s most innovative designers of manhole covers; Niels and Frank train rats to act as antipersonnel mine detectors; Jorge Rodolpho Fernández builds a monument to his hero, Jorge Luis Borges, out of cubes of crushed cars that he arranges in a pyramid on Las Vegas Boulevard; Solokhov is an avant-garde composer who makes symphonies using only the urban sounds that he records on the streets of Chicago; Phil and William, from Leicester, invent the sport of Extreme Ironing, which involves the competitive ironing of clothes in unlikely situations, such as while windsurfing or suspended from a moving truck—and even win sponsorship deals from the likes of Rowenta and Tefal; Ted and Hannah live in a micronation called Isotope in Utah; Che Guevara, it turns out, faked his death in Bolivia, and is amused, while on vacation in Vietnam, to find his features adorning T-shirts on sale there, but then gets knocked over by a motorbike and dies in a Vietnamese hospital; Pat Garrett collects found photos; Billy the Kid is a teenage rock-climber…

While Nevada is the most prominent location in Dream, we also cut from Madrid to Beijing, from a gas station near Almeria to a salmon factory on the northernmost cape of Denmark, from Paris to Mozambique. The narratives are mainly parsed out in short installments. Occasional links emerge in a piecemeal manner, but Mallo tends to evade the threat of significance inherent in the plots or character developments that one gets in more realist novels (Mallo defines his own fiction as “complex realism”). The characters and their stories, he implies, should be seen as nodes in a network, appearing and disappearing as randomly as a blog post spreading across the globe, then lapsing into oblivion. Falconetti, for instance, ends up abandoning his Columbus-inspired journey and returns to San Francisco, where he fulfills it by other means:

If he can’t make it all the way around the earth, he thinks, at least he can make the earth go around him. He buys a beachball-sized reproduction of the earth, draws a doll figure over San Francisco with a marker pen, and next to it writes his name. The next morning, he throws it into the East Bay.

And that’s the last we hear of Falconetti.

Born in Galicia, in the northwest corner of Spain, in 1967, Mallo trained as a physicist. In Palma de Mallorca, where he now lives, his day job involved developing X-ray systems with the aim of improving cancer radiation therapies. The scientific experiments undertaken in The Nocilla Trilogy, however, tend not to be the sort that attract grants and state-of-the-art lab facilities. Like Ben Marcus—a vociferous champion of Mallo’s fiction—he enjoys dramatizing implausible feats of hybridization. In Nocilla Experience (the second in the trilogy), we are introduced to Antón, who lives in Corcubión in Spain; Antón’s project is an attempt to crossbreed barnacles with computer hard-drives, yet his technique for achieving this is far from sophisticated; he simply buys hard-drives and sinks them into barnacle beds, with what results we never learn.

Advertisement

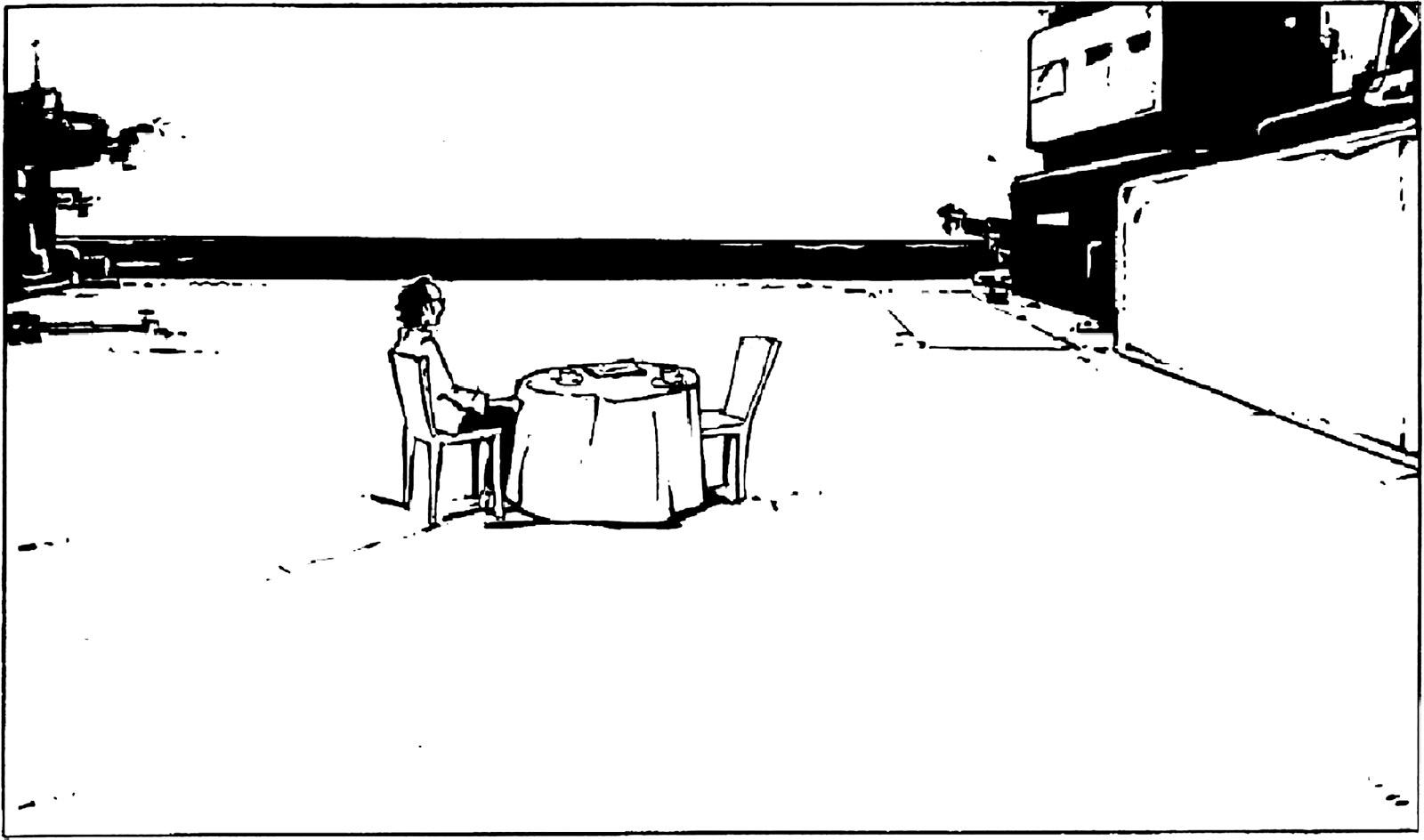

Most, but not all, of the schemes launched by Mallo’s intrepid band of visionaries are abandoned, although we do occasionally learn of an improbable success story. Steve, for example, is a chef with a difference, and his restaurant on Orange Street in Brooklyn gets booked up three or four months in advance. Steve’s signature dishes include Polaroids of the customers fried in batter; electric wiring in a Lebanese garlic-and-oil dish; carpaccio of work of literature (examples given are On the Road, the US Constitution, and Don Quixote) in pepper marinade; roasted blank CDs; and nude Spider-Man doll in carrot-and-leek broth. He is also the author of the classic Cooking with Your Car Compendium, which offers a series of recipes that can be cooked in the hot engine of a car by those undertaking long journeys and unwilling to stop at fast food outlets. His ultimate culinary dream is to cook the horizon, which he dubiously claims to have achieved by taking a group of customers onto the Brooklyn Bridge just before sunset:

Look, the horizon! The sun was going down, and it smoldered on that horizontal axis, it burned. There you have it! he cried. The group looked on in silence, utterly rapt at the vision, and applause broke out among them when the sun disappeared, and they toasted with red wine. Passing drivers rubbernecked. The event was reported in the news. During the Q&A on the TV program Cooking Today, someone asked him to reveal his secret. His answer: My secret is that I don’t bother with the insides of things, I cook the skins and the skins only; the skins of all objects, animals, things, and ideas are apt to be cooked, and this is to do with light and nothing else: the skins are the places the light reaches.

The aversion to interiority is rigorously maintained in parts 1 and 2 of The Nocilla Trilogy, but somewhat reversed in part 3. Lab is made up of three sections: “Automatic Search Engine,” “Automatic Engine,” and “Engine (Found Fragments).” A trilogy within a trilogy, it is best construed as a late version of the kind of avant-garde autofiction popularized by Paul Auster in his 1987 The New York Trilogy, in which the paradoxes of autobiographical writing are teased into a set of interlocking narratives featuring writers and their fictional doubles. Edgar Allan Poe’s classic doppelgänger short story “William Wilson” lurks behind both, and, like The New York Trilogy, Lab functions as a coded account of a relationship and the menace posed to it by the project of writing. We are encouraged throughout to see its narrator as Mallo himself.

But it is Auster’s The Music of Chance that Mallo chooses to reference in Lab. He, or his fictional avatar, buys it in Las Vegas in a translation into Portuguese (a language he hardly knows) the night after his unnamed partner slips from their bed in order to have sex with a US postal worker. Where Dream and Experience are deadpan and elliptical, much of the writing in Lab is expansive, self-circling, obsessive in its return to particular phrases, events, and locations. Javier Marías, the modern Spanish master of the extended compulsive reverie, as well as the intemperate Thomas Bernhard clearly influenced the style deployed by Mallo in the gigantic single sentence of “Automatic Search Engine.” Here is how he describes waking up at three in the morning in Las Vegas and finding himself alone in bed:

I reached across for her and she wasn’t there, and I waited 3 or 4 hours in darkness before realizing she’d slipped out to look for her cowboy-pirate, and, staring up at the stucco micro-pyramids, attempting to count them all, I imagined thousands of CCTV cameras looking down on her, I imagined her in their sights, her figure emitted via light rays onto screens and then out of the city, to a trash can at the ends of the desert, a trash can that contains blue, burned images, at the ends of the Internet, and, a little before dawn, she showed up, she came in without turning on the light, didn’t take a shower, did nothing, didn’t even get undressed, just lay down on the bed in silence, though when we got up in the morning, without me asking any questions, she confessed, she talked and talked for hours, I’d never seen her talk so much, nor look so gaunt, not in all the time I had known her, and I sat listening in silence, taking painkiller after painkiller…

That Mallo has his narrator in Lab resort to painkillers suggests his willingness to investigate subjectivity in a more personal, less scientific or theoretical way than he does in the first two books. The surrealistic aspects of this third volume tend not toward the weird and affectless but toward the Gothic and existential. We learn that Mallo and his partner are collaborators on some kind of project, which they are pursuing on an island south of Sardinia. They keep various materials relating to it stored in a waterproof Gibson Les Paul guitar case, but, after learning from their cat-sitter in Madrid that their cat has died, Mallo’s partner casts it into the sea.

Eventually they take up residence in an abandoned prison that has, in theory at least, been converted into an ecotourist resort. They are the only guests. The dense foliage in the inner courtyard, they are surprised to discover, is made entirely of plastic, while the proprietor is an elusive figure who reminds them of Emir Kusturica, the Serbian film director. He too is engaged on some great work, and when they visit him in his studio, they are aghast to find that it is the same project as theirs:

On the floor, next to his worktable, there lay the case for a Gibson Les Paul, black, and inside it what we could see were all the necessaries for the Project, our Project.

“Ah,” he said without looking at us, “this is what I’ve been working on.”

Then, looking us each in the eye, he said:

“It’s a project, an immense project. I’ve been so completely wrapped up in it, I’ve put aside my studies altogether.”

I couldn’t think of what to say; after a couple of seconds she spoke:

“Where did you get it?”

“Found it on the beach,” he said. “The sea washed up this guitar case. But that’s all I can tell you, it’s a secret, as I say, something immense.”

Mallo demands to know the proprietor’s name:

“Agustín, you already know the answer to that question.”

“No,” I insisted. “Your full name.”

“Agustín Fernández Mallo.”

As in Poe’s “William Wilson,” the struggle between doubles takes its inevitable violent turn, and the narrative accomplishes itself in a frenzied knife-attack by Mallo 1 on Mallo 2. Lab’s most original contribution to the doppelgänger tradition is the eruption of the plastic garden into horrifying life, its roots and tendrils invading the ecotourist hotel in which the narrator remains stubbornly holed up alone after the murder of his twin or alias—the unnamed partner having long since departed.

The final pages of Lab are occupied by a comic strip. Its opening panels depict Mallo finding a boat on a nearby beach and embarking for a mysterious installation off the coast, which turns out to be an oil rig. There he is greeted by his literary hero, Enrique Vila-Matas, who concludes The Nocilla Trilogy with a parable about a prisoner set free from a concrete cell in the desert. Literary comradeship, this coda suggests, can redeem Mallo from his solipsism; and, what’s more, his iconoclastic novelistic inventions happen to be just what the Spanish literary scene requires: “Come in, we’ve been waiting for you,” the rescuer in the parable declares, having at last drilled a hole through the wall of the cell, beckoning the prisoner into the outside world.

There may also be secreted here a metaphor for post-Franco Spain’s attempts to reconfigure itself in relation to the forces of globalization. The Nocilla Trilogy’s textual refractions of the ebb and flow of information, however disorienting, have been seen by many younger Spanish writers as opening a liberating space beyond the legacy of Franco’s dictatorship, as well as beyond constricting regional or tribal cultural affiliations. Indeed, a 2007 article called the writers prominent at a conference on new Spanish fiction held in Seville in June of that year “The Nocilla Generation.” Mallo’s status and reputation resemble those of, say, Tom McCarthy in Britain, or Ben Marcus in the US: like Remainder or The Flame Alphabet, The Nocilla Trilogy flaunts its defiance of the conventions of realist fiction, and invites us to participate in an artistic project commensurate with the complex reality that surrounds us.