Martin Scorsese’s much-anticipated new film, The Irishman, which premieres this week at the New York Film Festival and will be shown on Netflix this fall, purports to uncover the truth behind one of the most famous unsolved crimes in American history: the disappearance and presumed murder of former Teamsters leader Jimmy Hoffa on July 30, 1975. “True crime” films often take license with factual details. But The Irishman goes well beyond these conventions, since the entire story is premised on a confession that is not credible.

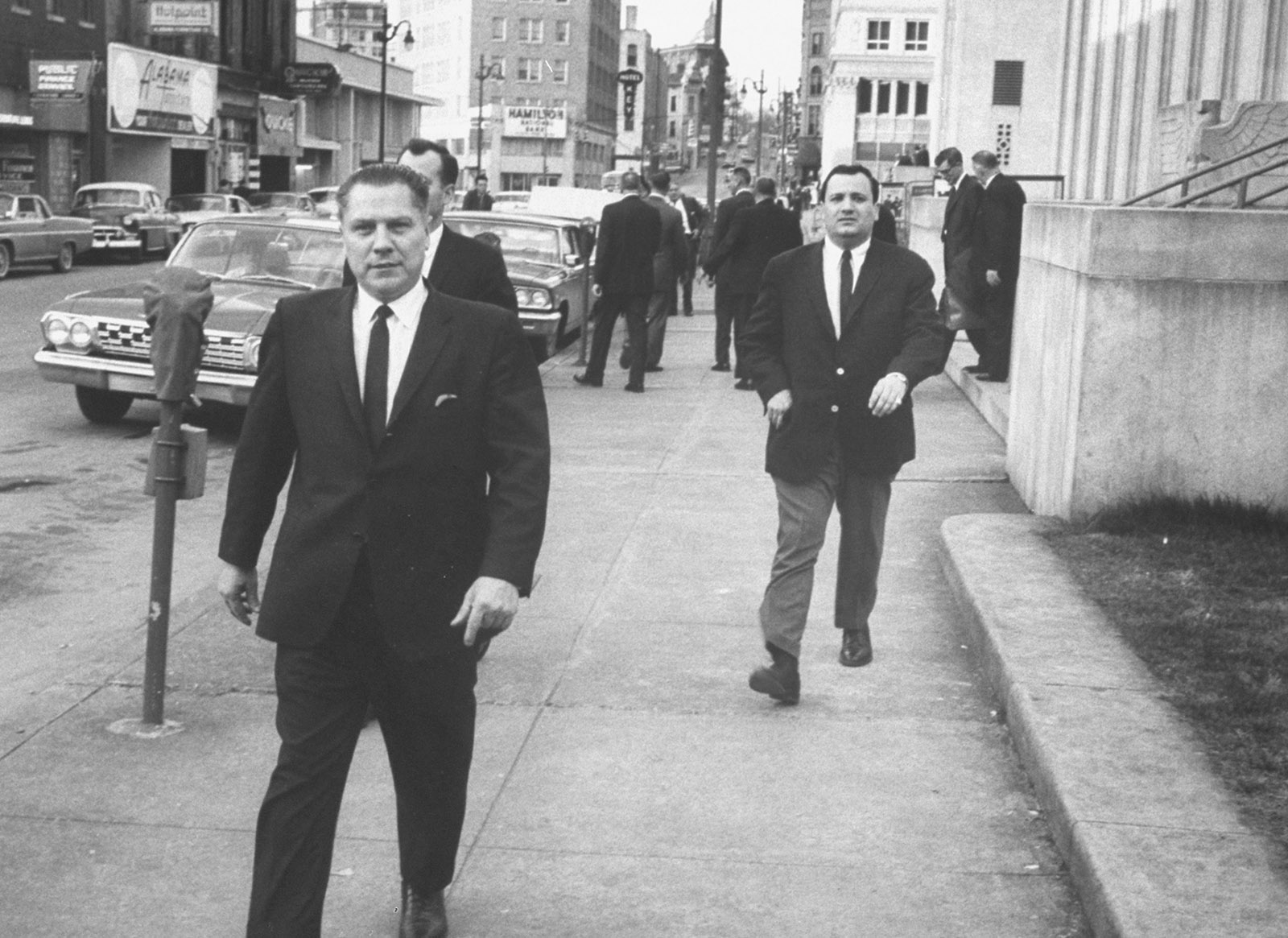

As president of the powerful but corrupt and mob-linked Teamsters Union, Hoffa was the nation’s best-known labor leader in the 1950s and 1960s. The government hounded him for a decade for his serial lawbreaking, and finally sent him to prison in 1967. After President Richard Nixon commuted his sentence in 1971, Hoffa was seeking to regain control of his union when he mysteriously vanished from a parking lot next to the Machus Red Fox restaurant in a suburban Detroit shopping plaza.

The investigation into Hoffa’s disappearance was, from the outset, “shoulder-deep in a rat’s nest of rumors and speculation,” as the Detroit Free Press reported three days after the event. The FBI was overwhelmed with tips from organized crime informants, union officials, supposed eyewitnesses to the crime and burial, and a bevy of mystics and dreamers who purported to know Hoffa’s fate. The Bureau eventually uncovered evidence about a mob conspiracy to kill Hoffa, but never solved the crime.

In the forty-four years since Hoffa vanished, several people have falsely confessed to the crime, and federal and state officials, acting on tips, have torn up a dozen barns, pools, or fields in Michigan and elsewhere looking for Hoffa’s remains. These searches were all fruitless and the case remains open today.

The Irishman purports to do what the FBI and others seem unable to do: tell us who killed Hoffa, and how. The film is based on a 2004 book by Charles Brandt called I Heard You Paint Houses (the title alludes to supposed mob slang for carrying out a hit). The book’s central claim is that Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran murdered Hoffa. Sheeran was a Teamsters official in Delaware, an associate of Hoffa’s as well as senior mob figures, and a well-known boozer and thug. Brandt’s book recounts Sheeran’s confession to the murder, and describes the house where he claims the murder happened.

I have a personal stake in the veracity of Sheeran’s confession. Sheeran repeats the public conventional wisdom since 1975 that a man named Charles “Chuckie” O’Brien drove the car that picked up Hoffa from the suburban parking lot and delivered him to his killers. O’Brien was Hoffa’s closest aide for decades. He is also my stepfather. I was twelve years old when Hoffa disappeared, and I lived through the bedlam of the Hoffa investigation.

Chuckie and I were close when I was a boy, but later, when I was in law school and worried about the effect of our relationship on my career, I cut him out of my life. We reconciled in 2004, soon after I finished my service as a senior legal adviser in the Justice Department. In subsequent conversations with Chuckie, I began to believe, as he had always claimed, that he was innocent. I spent seven years investigating the matter. In my new book (published this week), In Hoffa’s Shadow, I attempt to show—among other major revisions to the Hoffa story—that my stepfather did not take part in Hoffa’s murder.

Sheeran’s is not the only account of Hoffa’s disappearance to implicate Chuckie, but thanks to the Scorsese movie, it is set to become by far the most influential. My book does not, however, address Sheeran’s supposed role in Hoffa’s murder, since I, like many people who have studied the Hoffa case in depth, find it preposterous. Inevitably, though, the cinematic adaptation of Brandt’s book will elevate Sheeran’s tale to conventional wisdom. I believe it is important to try to set the record straight for the sake of my stepfather’s reputation. And it is also important that we move beyond the decades-long obsession with who killed Hoffa in order to understand the larger historical significance of his life and death.

*

Sheeran was on the original FBI longlist of possible suspects, and for the first twenty years after Hoffa’s disappearance, he proclaimed his innocence and denied knowledge of Hoffa’s fate. Starting in 1995, however, he began to tell a different story—several different, contradictory stories, in fact—in an apparent effort to get a book contract.

Advertisement

In January that year, Sheeran told a newspaper reporter that contract killers linked to the Nixon White House killed Hoffa, but that the body would never be found. The following year, he claimed to have diagrams that showed where Hoffa’s body could be found, and said that Vietnamese mercenaries had done the deed at the behest of Nixon and his attorney general, John Mitchell. Neither tale resulted in a book deal.

Then, just before he entered a nursing home in 2001, Sheeran said that he was involved in Hoffa’s murder. NBC almost ran his story—once in 2001, and then again in 2003, when Sheeran claimed to be the hitman. But it ultimately declined to do so. “My bosses decided that Sheeran has made too many claims proven false over the years to be believed now,” an NBC executive told the journalist and Hoffa expert Dan Moldea at the time. “So we are passing on the story.”

Sheeran died on December 14, 2003. Within six months, three differing purported confessions by Sheeran came to light. First, John Zeitts—who was working on a biography of Sheeran—produced a signed confession in which Sheeran claimed to have disposed of Hoffa’s body but not to have murdered him. Sheeran’s daughter, Dolores, however, dismissed the document as a forgery. Zeitts also had tapes of conversations in which, according to Moldea in an afterword to the 1993 edition of his book The Hoffa Wars, he and Sheeran had “concocted a couple of different scenarios—both of which proclaimed Sheeran’s complete innocence and lack of involvement in the Hoffa murder.”

Second, Harry Jay Katz, a profligate entrepreneur from Philadelphia who at one time acted as Sheeran’s agent, said that Sheeran told him back in 1996 that he had shot Hoffa in a car and then driven the body to an undisclosed location, where it was destroyed.

The third confession was the one that appeared in Brandt’s book. Brandt had been a Delaware medical malpractice attorney when, in 1991, he got a call from a member of the Philly mob on behalf of Sheeran, who was in jail and suffering from arthritis of the spine. Thanks to Brandt’s efforts, Sheeran was released early. Brandt interviewed Sheeran briefly in 1991, and then for hundreds of hours between 1999 and 2003. Using interrogation techniques he says he learned during a stint as chief deputy attorney general of Delaware, Brandt extracted Sheeran’s confession. It never came in a single account, but rather in multiple conversations, on and off tape.

Because the story Sheeran told Brandt originally involved a purported letter from Hoffa that, as Brandt relates, Sheeran had forged, the first publisher for Brandt’s book backed out. Brandt’s agent told Sheeran that to get another publisher, Sheeran would have to vouch for the book explicitly. Six weeks before he died, sitting in his hospital bed, Sheeran did so. Brandt turned on a video camera and handed Sheeran a copy of the book, and then initiated a conversation. Toward the end of the book, Brandt provides a transcript of the exchange.

“Now, you read this book. The things that are in there about Jimmy and what happened to him are things that you told me, isn’t that right?” asked Brandt.

“That’s right,” replied Sheeran.

“And you stand behind them?” Brandt pressed.

“I stand behind what’s written,” said Sheeran. Soon after Sheeran made this statement, Brandt says, his camera battery died.

Brandt never published the entire confession video, but on request he gave a copy to FBI agent Andrew Sluss, in 2008. At that time, Sluss had been the lead investigator on the Hoffa case for almost fifteen years, and knew it better than anyone. He viewed the tape carefully several times, but immediately concluded that Sheeran’s story lacked all credibility. “Seeing is believing, except in this case, then seeing becomes disbelieving,” Sluss told me, some years ago. “The video I saw of Sheeran was a laughable, sad, desperate attempt to create a record.”

*

According to Sheeran’s account of the killing, as told in Brandt’s book, he and an East Pennsylvania crime boss named Russell Bufalino planned to drive with their wives from Kingston, Pennsylvania to Detroit to attend a wedding on Friday, August 1, 1975. They were scheduled to drive to Detroit on Tuesday, July 29—the day before Hoffa disappeared. Sheeran said that shortly before the trip, Hoffa called him and told him about a meeting at 2:30 PM on July 30 at the Machus Red Fox restaurant with two mobsters—Detroit capo Anthony Giacalone and New Jersey capo Anthony Provenzano, who was also a Teamsters official and a one-time ally of Hoffa’s. Sheeran says Hoffa knew that he would be in town and asked Sheeran to join him at the restaurant half an hour beforehand, to be Hoffa’s security at the meeting. Sheeran agreed and said he would bring a weapon.

Advertisement

Sheeran says that over dinner on Monday night near Kingston, Bufalino informed him that they would delay their departure for Detroit until Wednesday, July 30, and that, along the route that day, Sheeran would run an “errand” for him: to murder Hoffa. When they reached Port Clinton, Ohio, on Wednesday, the men dropped off their wives at a restaurant and then Bufalino drove Sheeran to a local airport. Sheeran took a private plane to an airport near Detroit, got into a Ford with keys in it, and drove to a home in Detroit. Waiting there were three associates of Provenzano’s—Sal Briguglio, Steve Andretta, and another man.

It was then, according to Sheeran, that my stepfather arrived to pick the men up. Briguglio got in the back seat of the car, Sheeran in the front. Chuckie drove the men to the Machus Red Fox, where they approached the waiting Hoffa. After a brief discussion, Hoffa joined Briguglio, whom he did not know, in the back seat. The group drove back to the home where they had originally met. Briguglio, Sheeran, and Hoffa all got out of the car; then Briguglio got back in the front seat, and he and O’Brien drove away.

Hoffa and Sheeran walked in the front door. When Hoffa saw that the house was empty, he realized he’d been duped. He made for the door, but Sheeran drew his weapon, and Hoffa “got shot twice at a decent range” in the back of the head. Sheeran then dropped his weapon, got in the Ford, drove back to the airport and then flew back to Ohio, where Bufalino picked him up to resume the trip to Detroit with their wives. He implies that Andretta and the other man, who had been hiding in the house, put Hoffa in a body bag and took him to be cremated.

*

Brandt’s book weaves Sheeran’s claims into the details of the FBI theory of the Hoffa case that circulated publicly in the late 1970s. But he offers no direct corroborating evidence for Sheeran’s involvement in the murder or the other novel elements of Sheeran’s confession. And some claims in the book are belied by the public record. The book’s first paragraph, for example, states that “the FBI found a yellow pad” at Hoffa’s Lake house on which “Hoffa had written in pencil ‘Russ & Frank,” an apparent reference to Sheeran and Bufalino, and a frame for the book’s thesis. But the FBI found no such note. The only note pertinent to the disappearance that agents discovered concerned Hoffa’s planned meeting with Anthony Giacalone on the day of the disappearance.

To bolster Sheeran’s confession, Brandt has long claimed that the FBI agrees with it. Brandt says that a 1976 FBI document about the case known as the Hoffex memorandum supports Sheeran’s confession, and also maintains that all the details Sheeran described “were all later corroborated by the FBI.”

The Hoffex memorandum does name Sheeran—as the last of twelve possible suspects—but it doesn’t link him factually to Hoffa’s disappearance, much less affirm his confession. The memo was the work of a now-retired Detroit FBI agent named Robert Garrity. I have spoken to Garrity on more than a dozen occasions over the last seven years. He stands by his report but does not believe it corroborates Sheeran’s confession. Brandt says that Garrity told him, “We always liked Sheeran for it [the murder].” But Garrity told me recently that he could only say that he “cannot exclude” Sheeran. I asked Garrity if he knows of any evidence to support Sheeran’s confession; he said that he did not.

I have also interviewed three other original lead FBI investigators on the Hoffa case from the 1970s: Jim Dooley in New Jersey, Al Sproule in New York, and Jim Esposito in Detroit. They each told me that they, too, know of no evidence to support Sheeran’s confession, and further, do not believe it. Dooley specifically told me that, prior to what he calls “Sheeran’s entirely false confession,” the Irishman “was never on the radar screen as one of Hoffa’s killers in the view of anybody in the FBI who knew anything about the case.”

And then there is Andrew Sluss, the case agent on the Hoffa investigation when Brandt’s book came out. Brandt has suggested that Sluss believes Sheeran’s confession. He did so once on April 20, 2017, during a talk about his book to an audience at the Lorenzo Cultural Center in Clinton Township, not far from Detroit.

Unbeknownst to Brandt, Sluss was in the audience, about halfway back in the large auditorium, along with three former FBI colleagues, all veterans of the Hoffa case. He had spoken to Brandt one or two times over the telephone, and had given him no reason to think he agreed with Sheeran’s story. Indeed, Sluss had long believed that Sheeran’s confessed involvement in Hoffa’s murder was absurd. He and his colleagues had come the Lorenzo Cultural Center to have an evening of entertainment at what Brandt had to say.

During the presentation, Sluss and his friends passed around notes expressing their amused skepticism. “Why didn’t those interviews make the file?” Sluss scribbled, when Brandt claimed to have turned over all of his recorded interviews with Sheeran to the FBI.

The capper came when Brandt tried to burnish his bona fides with the FBI. “Andy Sluss and I, we’re like this,” Brandt told the audience, with his fingers interlocked to indicate how tight the two men were. One of Sluss’s companions turned to him, eyebrows arched, and smiled. Since Sluss was eighteen, he had always gone by “Andrew,” never “Andy,” and his colleagues knew it.

*

There are many reasons to doubt Sheeran’s confession other than the absence of supporting evidence and his own history of conflicting and fantastical accounts of the Hoffa disappearance. In March 2004, for example, a Fox News team, accompanied by retired Michigan state police officers, visited the house on Beaverland Street, where Sheeran says the Hoffa hit occurred, and found blood stains on the floorboards in the entrance. These were subsequently sent to an FBI lab at Quantico for analysis. DNA tests concluded that the blood was not Hoffa’s.

That doesn’t by itself disprove Sheeran’s claims, but other problems inhere in his story. Why, at the eleventh hour, would the mob conspirators involve Sheeran, a long-time Hoffa loyalist, with the attendant uncertainty about how he might behave, and with so many unnecessary loose ends, exposures, and witnesses at the airports and elsewhere—especially when, in Sheeran’s telling, they had three Provenzano heavies already in Detroit? Why, too, would the mob boss Russell Bufalino remain in close company with Sheeran immediately before and after the murder? As one former FBI agent, an expert on the mob, told me: “It would be the first time that a La Cosa Nostra boss drove the ‘shooter’ en route to a hit—and the boss even took his wife along for the ride!”

Sheeran has no credible account for why he was involved. He implied in Brandt’s book that Bufalino sent him to kill Hoffa to test whether Sheeran was more loyal to Hoffa or to the mob. But it is highly implausible that the mob would have devised a live exam for Sheeran, under such strange circumstances, for the murder of the century. And the mob didn’t need Sheeran to allay suspicions Hoffa might have had about getting in the car; the presence of Chuckie O’Brien—there, in Sheeran’s telling—would have accomplished that, since he knew Hoffa better than anyone.

By his own account, Sheeran’s arrival at the Machus Red Fox would have been a bright red flag to Hoffa, whom we know was very anxious on the day he died. The FBI established that Hoffa was expecting to meet Anthony Giacalone that afternoon and had called his wife to complain angrily that Giacalone was late. Sheeran says he had previously told Hoffa that he would telephone him on Tuesday and be at the restaurant at 2 PM to protect him. He did neither thing. And yet, despite the jarring facts that Hoffa expected to meet Giacalone and not the men who drove up very late to collect him, that Hoffa believed the meeting was supposed to be in the parking lot itself, that Sheeran had failed to call Hoffa on Tuesday and was unpunctual on Wednesday, and that Hoffa did not know the thuggish-looking man in the back seat, Hoffa got in the car, Sheeran says.

A different problem for Sheeran’s story grows out of meetings Sheeran says he had with senior mafia figures at the Vesuvio Restaurant on 45th Street in New York on August 4, 1975, five days after Hoffa’s disappearance. One was arranged by Anthony Provenzano, who, unlike Sheeran, was a central suspect in the case. Sheeran says Provenzano was furious with him because Sheeran knew that Hoffa wanted Provenzano killed. In Sheeran’s telling, other mobsters intervened to save Sheeran’s life by persuading Provenzano that he knew nothing.

This story, like others from Sheeran, is a variation of a known tale. This one was first told publicly in 1980 by Charlie Allen, a career criminal who knew Hoffa, had carried out crimes commissioned by Sheeran, and was also at Vesuvio that day. But the Vesuvio meeting makes it impossible to believe that Sheeran was involved in the plot to kill Hoffa. If Sheeran were the assassin, or even involved in the deed, Provenzano would never be meeting him in public, much less haggling about Sheeran’s loyalties, five days after Hoffa’s disappearance. If the purpose of using Sheeran to pull the trigger had been to extract proof of his loyalty to the mob, then the Vesuvio meeting makes no sense: Provenzano would have known that Sheeran had already passed the test.

The journalists Andy Petepiece and Bill Tonelli have documented other improbable claims of Sheeran’s that appear in the Brandt book, including that he drove Buffalo crime boss Russell Bufalino to the famous 1957 Apalachin gathering of senior mob figures, and that he murdered gangster Joey Gallo in 1972. As Petepiece and Tonelli show, these and other assertions are belied by credible public reporting. Both men refer to Sheeran skeptically as the “Forrest Gump of organized crime.”

*

Why does it matter whether Sheeran’s tale is fabricated? After all, it is undeniable that Hoffa disappeared on July 30, 1975, and was murdered at the behest of the mob, which feared, among other things, that Hoffa might spill the beans about its takeover of the Teamsters Union pension fund. Sheeran was not the hitman. But as I report in my book, the Detroit FBI believes it was someone like him—someone who was from Detroit, acting with similar motives and under similar orders.

Given that the general contours of the Hoffa hit are the same whoever pulled the trigger, one might think that the moral drama of the murder as Martin Scorsese imagines it is what counts, not the identity of the murderer.

But Scorsese’s imprimatur on Sheeran’s tale matters, for it falsely implicates a real person in the crime, my stepfather. Because of an early FBI theory of the case that became publicly known, Chuckie O’Brien has for forty-four years been seen as the man who picked up Hoffa at the Machus Red Fox and drove him to his death. As I report in my book, the government’s early circumstantial case against Chuckie did not hold up, and agents who have worked the case for the last quarter-century came to believe that he was not involved. The Irishman threatens to put my stepfather back in the center of the frame indefinitely.

On another level, however, the forty-four year whodunnit obsession—which The Irishman will almost certainly perpetuate—also distracts us from the larger and still-relevant lessons the Hoffa saga can teach. In the late 1950s, Hoffa ran the largest union in the country, and his stranglehold over transportation routes gave him extraordinary power against management interests and thus enormous influence over the national economy. It was a precarious time for the increasingly sclerotic American labor movement, which was just beginning its long decline toward its present, comparatively pitiful state. Hoffa might have used his genius for organizing and his control over transportation networks to lead the labor movement in a very different direction than the one it in fact took. But Hoffa’s amorality and criminal associations made this impossible—and would destroy him.

Hoffa’s demise had tragic consequences for all of labor. To bring Hoffa down, a young Robert F. Kennedy, leading a Senate investigation known as the McClellan Committee, engaged in famously abusive and broad-brush tactics that had the effect of making large parts of the American public think that unions had grown into dangerously powerful institutions that threatened America’s economy and even its moral sense. The righteous Boston liberal gave the post-World War II conservative critique of American unions a broad public audience and a credibility that anti-labor forces in the business community and Congress never could have achieved. As the labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein has noted, the McClellan Committee hearings had a “devastating impact on the moral standing of the entire trade-union world” and “marked a true shift in the public perception of American trade unionism and of the collective-bargaining system within which it was embedded.”

Bobby Kennedy continued the abusive tactics of what had become a vendetta against Hoffa when he was Attorney General in his brother John’s administration. Kennedy finally got his man with two criminal convictions in 1964. He had always assumed that removing Hoffa from the Teamsters would eliminate the mob’s influence on the union, but he never realized that Hoffa, despite his turpitude, was keeping the organized crime relatively at bay. When Hoffa went to jail in 1967, the mob infiltrated the union and gorged on its pension funds as never before.

That irony was soon compounded by another. Hoffa’s threat, after his release from prison, to upset the mob’s happy arrangement with the Teamsters is what got him killed. And it was the notorious Hoffa hit that finally roused the federal government, after decades of fiddling, to commit the resources and imagination needed to really understand the problem of labor racketeering and, eventually, to break the mob’s hold on the Teamsters Union, and its criminal power more generally. As Al Sproule, an FBI agent who worked the Hoffa case from New York in the 1970s, told me, “If Jimmy was left in the street, a lot of people would not have gone to prison and the Teamsters Union and ‘organized crime’ would not have been affected as dramatically as they have been.”

As I explain in my book, Hoffa’s life was thus at the center of some of the most consequential themes in postwar American history, the repercussions of which are still very much with us: the rise and decline of American labor; La Cosa Nostra’s hugely profitable illicit control of the underworld for much of the twentieth century; the federal government’s often hapless but ultimately effective efforts to squelch both labor and the mob; and the government’s double standards and overreach in pursuit of various enemies within.

It is possible that Scorsese’s cinematic genius will draw out these larger themes. We will soon see. But even as Sheeran’s story comes to our screens, Charles Brandt is working on his next book. It is about who really murdered JFK.