There is no longer any doubt that President Trump’s demonization of certain groups—immigrants in particular, but also his political opponents—has emboldened American right-wing extremists to commit violent acts. In the fall of 2018, just before the midterm elections, Cesar Sayoc Jr., a fanatical Trump supporter, sent pipe bombs to thirteen prominent Democrats—they were apparently not designed to explode, only to frighten the recipients—and Robert Bowers, an anti-immigration extremist, killed eleven worshippers at a Pittsburgh synagogue in the deadliest anti-Semitic attack in US history. In August 2019 Patrick Crusius, a white nationalist, murdered twenty-two people at a Walmart in a Hispanic neighborhood of El Paso. A few days later, the FBI arrested Eric Lin, a neo-Nazi, for threatening a Hispanic woman on Facebook, where he proclaimed that Trump would “launch a Racial War and Crusade.”

Trump has called immigration from south of the border an “invasion” and deployed thousands of troops to stop it. He has falsely claimed that Latin American immigrants are more likely to commit crimes than American citizens, and that large numbers of jihadists are infiltrating the US from Mexico. The manifesto posted online by Crusius adopted Trump’s anti-immigration rhetoric, stating that “this attack is a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas.”1 Sociologists call mayhem based on public political statements “scripted violence.”2 Crusius’s mass murder was a flagrant example of it.

In August 2017 the president intimated moral equivalence between “Unite the Right” demonstrators—including self-identified neo-Nazis, neo-Confederates, neofascists, and white nationalists, as well as various militias—and counterprotesters in Charlottesville, Virginia. There had been, he told reporters, “some very fine people on both sides.” He has vilified black professional football players for protesting police violence against African-Americans by kneeling during the national anthem, and he routinely insults nonwhite journalists and politicians. He has told several progressive, nonwhite congresswomen to “go back” to their countries, though all but one were born in the United States. At a political rally in Indiana in November 2018, Trump both exaggerated the threat posed by left-wing activists and belittled their strength, calling on presumably more muscular supporters—bikers, the police, the military—to confront them and giving the “Q” sign associated with white supremacy to someone in the crowd.3 As William Saletan observed in Slate:

When Muslims commit acts of terror, Trump blames radical imams and their ideology. When white racists commit acts of terror, Trump says racial propagandists have nothing to do with it. That’s because Trump’s beef isn’t really with incitement. It’s with Muslims and immigrants. He’s fine with incitement—very fine—as long as the incitement is his own.4

Right-wing violence has increased since Trump became president.5 According to the FBI, hate crimes, which by definition mostly target people because of their race or ethnicity, and are generally undercounted, increased by 17 percent in 2017; anti-Semitic crimes in particular increased by 37 percent.6 The Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism has attributed 387 killings in the US between 2008 and 2017 to domestic extremists; 71 percent of these were committed by right-wing extremists, 26 percent by Islamist extremists, and only 3 percent by left-wing extremists. According to testimony presented to Congress last June, in 2018 there were fifty murders committed by perpetrators connected to right-wing extremists; 78 percent of them were white supremacists.7

Despite these statistics, the Trump administration has persistently deemphasized right-wing extremism as a national law enforcement and intelligence concern, and focused narrowly on the Islamist variety. In 2018 a Department of Homeland Security report claimed that 73 percent of those convicted of international terrorism–related charges were “foreign-born,” thus excluding those convicted of or charged with domestic terrorism–related offenses.8 Under pressure from lawsuits brought by watchdog and civil liberties groups, the Justice Department has admitted that the report is erroneous and misleading but has refused to retract or correct it.9 Amplifying the distortion, Trump falsely stated in a tweet that the report “shows that nearly 3 in 4 individuals convicted of terrorism-related charges are foreign-born.”

Crusius in his manifesto stressed that his malignant views predated Trump’s presidency, and racist ideas of course have a long history in the US. Manifest Destiny and its precursors always had a racial dimension—manifest, as it were, in the systematic eradication of Native Americans as part of the grand vision of a distinctly Caucasian democracy. The institution of slavery undergirded this vision, which did not merely survive African-American emancipation but became even more toxic in reaction to it—at the overt civic level in the form of Jim Crow and the vigilante racism of government agencies like the Texas Rangers and the US Border Patrol, and at the underground criminal level through organizations like the Ku Klux Klan—and was bolstered by the Spanish-American War and subsequent American colonialism.

Advertisement

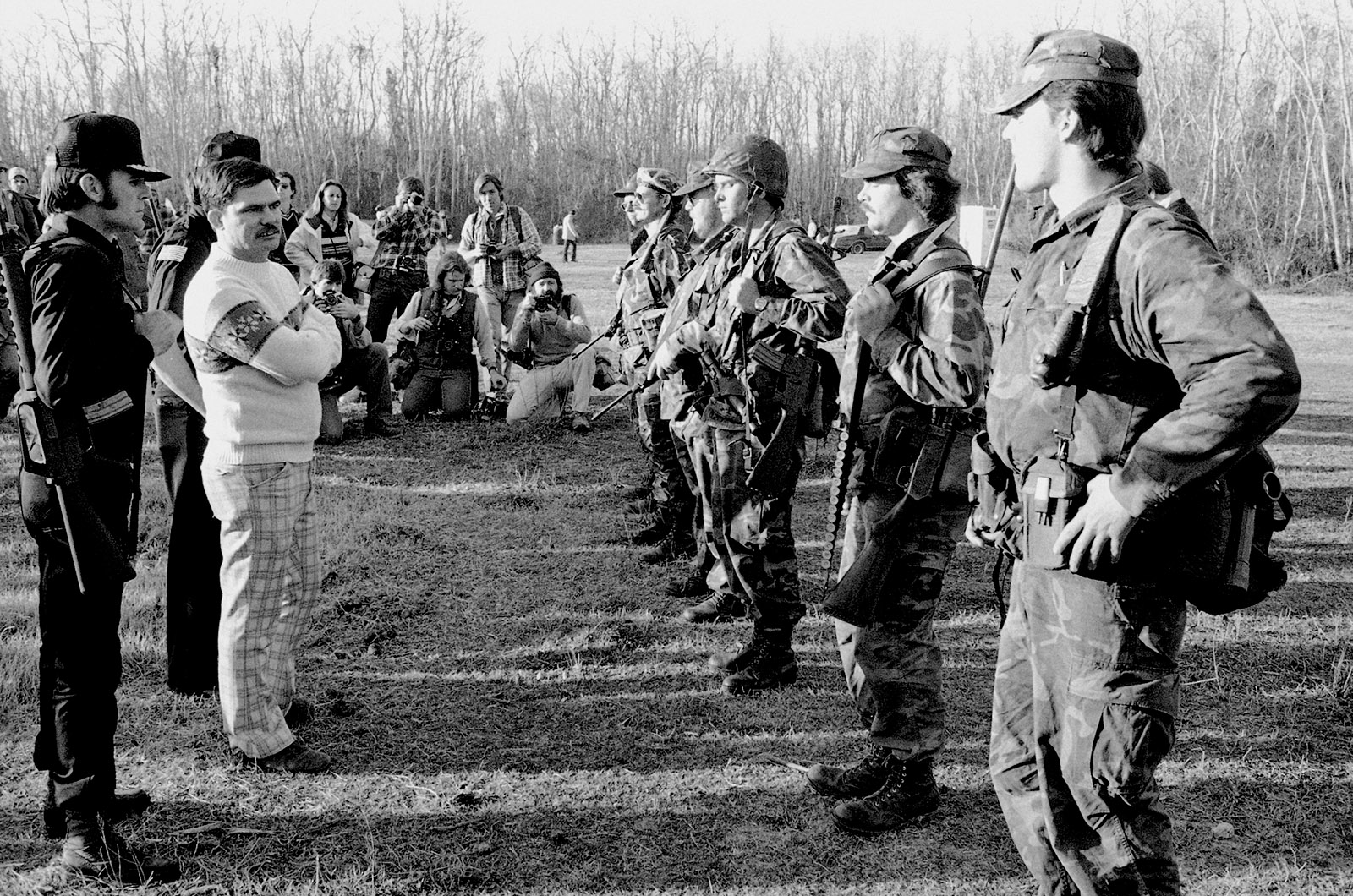

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, despite its political successes, did not extinguish white nationalism, which became less visible but was susceptible to even nastier strains of extremism sometimes embraced by embittered Vietnam veterans.10 The white supremacist and Klan member Louis Beam, a decorated helicopter gunner, returned home to Texas from Vietnam in 1968 convinced that the US government had abandoned POWs in Southeast Asia. He developed military-style training camps for the Klan, recruited like-minded veterans, and formed an elite paramilitary Klan unit that violently targeted Latin American immigrants and Vietnamese refugees.

But the charismatic Beam disliked the covert nature of the Klan; in the mid-1970s he broke away and formed an independent white supremacist outfit, eventually attracting neo-Nazis and affiliating with David Duke’s unabashedly public and national Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, based in Louisiana, and with the organization Aryan Nations, which had formed in the western US. At the same time, he advocated “leaderless resistance”—cell-based local initiatives and actions that were less vulnerable to infiltration by law enforcement—in the militia movement.

The national paramilitary movement known as the Order, which coalesced in the early 1980s, was based on leaderless resistance and guided by The Turner Diaries, a novel by William Pierce, head of the neo-Nazi group National Alliance. The book envisaged a white utopia wrought by a race war and genocidal purgation. While the movement found cryptic encouragement in Ronald Reagan’s anti-statism, it opposed the federal government, which it perceived as having betrayed US soldiers in Vietnam—a crucial origin myth—and as advancing un-Christian and dangerously leftist and internationalist policies.

By the early 1990s, incidents like the Ruby Ridge and Waco confrontations between extremists and federal law enforcement officers, together with the growing capacity of the Internet to spread political propaganda, were quietly galvanizing right-wing activists in the United States. In 1995 Timothy McVeigh bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people. Although he insisted that he had acted alone, McVeigh enlisted several accomplices and had absorbed the white-power mentality that had been developing for decades.

Beam cast the bombing as a call to action, and it inspired other right-wing militia operations in the mid- to late 1990s. A copycat bombing in Vacaville, California, injured a federal mine inspector and his wife. Federal officers broke up several plots to target federal facilities, including the FBI’s national fingerprint center. Eric Rudolph, a white separatist, killed two people and injured 117 in bombings at Atlanta’s Centennial Park during the 1996 Summer Olympics and at two abortion clinics and a gay bar over the following two years. The wave of terrorist activity prompted a federal law enforcement crackdown that effectively suppressed it by the early 2000s.11

During this period, the ethnonationalist terrorism that had plagued Europe was declining, as the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Basque nationalist group Euskadi ta Askatasuna (ETA) wound down their long-standing armed campaigns and moved toward predominantly nonviolent political strategies, and far-left organizations like the Red Brigades in Italy and Greece’s 17 November Group became enervated. At the same time, jihadist terrorism was steadily increasing. The 1993 attack on the World Trade Center, al-Qaeda’s 1998 US embassy bombings in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, and its 2000 attack on the USS Cole in Yemen are three prominent examples. The concerns about jihadism in the United States and Europe that were intensified by the September 11 attacks—and later by the 2004 attacks in Madrid, the 2005 attacks in London, and many others—almost completely crowded out residual worries about right-wing terrorism. In 2005 the Department of Homeland Security had only one analyst working on non-Islamist terrorist threats.12

A critical surge in right-wing extremism occurred when Obama was elected president. Immediately afterward, according to the economist Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, one in a hundred Google searches for “Obama” also included “KKK” or “nigger.”13 Stormfront.org, founded in 1995 by a former Ku Klux Klan leader and at the time America’s most popular online hate site for white nationalists, saw by far its largest single increase in membership on November 5, 2008—the day after Obama’s election.14

Janet Napolitano, Obama’s secretary of homeland security, understood the potential synergies between extremist movements and a burgeoning population of US veterans with weapons training disaffected by their experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq or wrestling with post-combat social readjustment, and she saw a need to increase domestic counterterrorism efforts. In 2009 the DHS’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis warned that right-wing extremism was on the rise. In 2014 Eric Holder, Obama’s attorney general, reactivated the Department of Justice’s Domestic Terrorism Executive Committee, which had been established in response to the Oklahoma City bombing but had not met for thirteen years and had no budget or staff. Congressional Republicans objected to the Obama administration’s domestic counterterrorism mobilization, casting it as a partisan effort to demonize those whose views diverged from the liberal mainstream that Obama represented. Anemic funding and staffing severely limited the committee’s effectiveness.15 Meanwhile, high-profile jihadist terrorist operations like the Boston Marathon attacks in 2013 further diverted attention from right-wing terrorism.

Advertisement

More recently, according to a report by the Soufan Center, a New York–based think tank founded by former FBI special agent Ali Soufan, the US military is struggling to expunge white supremacy within its ranks: US white supremacist groups like the Atomwaffen Division and the Rise Above Movement have recruited active-duty American soldiers, and the membership of veterans in such groups surges as major American wars end.16 These facts indicate that there is a large potential pool of capable and dangerous operatives.

Furthermore, extremists today can draw on a bigger, broader range of ideological inspirations: one of Crusius’s was the anti-Muslim massacre perpetrated last March by Brenton Tarrant, an Australian, in Christchurch, New Zealand, in which fifty-one people were killed.17 Tarrant, now revered worldwide by white supremacists, wrote a seventy-four-page manifesto that was based on extremist views he found on social media—in particular the online writings of Dylann Roof, who shot and killed nine African-Americans at a church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015. Tarrant was also inspired by the white supremacist Anders Breivik’s murder of seventy-seven students in Norway in 2011. In his screed, Tarrant openly celebrated fascism, extolled Donald Trump “as a symbol of renewed white identity and common purpose,” and wrote that he chose guns as his weapons specifically “to create conflict between the two ideologies within the United States on the ownership of firearms in order to further the social, cultural, political, and racial divide.”18

Earlier white supremacist paramilitary movements opposed the federal government, but many today support the current US government, which they consider sympathetic to their cause. They have distilled their fears into the idea of “replacement,” whereby the white race will be decimated by intermarriage, immigration, and demographic shifts unless violent action is taken. White nationalist attitudes have become much more public, often cloaked in the euphemistic notion of “race realism,” according to which finite resources require nations to become racially homogenous—and the United States exclusively Anglo-Saxon. Indeed, this idea is an ideological underpinning of Trump’s border wall.

Trump himself has tacitly encouraged his supporters to take up arms, tweeting on September 29 a quote from Fox News contributor and Texas megachurch pastor Robert Jeffress that his removal via the impeachment process would “cause a Civil War like fracture” and referring to the House of Representatives’ impeachment inquiry as a “coup.”19 The Oath Keepers, an armed far-right militia, construed these public pronouncements as indications that we “ARE on the verge of a HOT civil war.” At a conference at one of Trump’s Florida golf resorts in October, American Priority, a pro-Trump group, screened a gruesome spoof video, tagged with a Trump 2020 campaign logo, of him shooting, stabbing, and beating a wide array of political and media opponents. These unsettling political phenomena reflect an American white power movement that now conceives of itself as something close to a pro-government effort.

More troubling still, the transnational cross-fertilization of right-wing terrorism suggests that a networked global threat, structurally akin to the jihadist one, may be emerging. Ukraine appears to be a hub. Two American GIs who deserted and have been indicted for murder apparently met while fighting for a far-right Ukrainian group called the Right Sector. One of them had mentored Jarrett William Smith, a soldier based at Fort Riley who was arrested in September. Smith had told undercover FBI agents of his plans to attack CNN, suggested that Beto O’Rourke would be a good target for assassination, and planned to travel to Ukraine to join an elite white supremacist element of the Ukraine military that actively recruits Western fighters.

More broadly, the evolution of jihadist terrorism reflects the power of the Internet to build networks of disparate local groups,20 while Russian intelligence’s broad-gauge manipulation of such groups in Europe demonstrates the ability of committed state agents to orchestrate the expansion of the groups’ operations and impact. National leaders who appear even tacitly sympathetic to the far right and to extralegal violence, such as Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte and Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, reinforce these movements’ determination and validate their extremism.

Right-wing nationalist sentiment has long been latent in Europe, where Nazi and fascist ideology was never fully extinguished. Italy’s “Years of Lead,” between the late 1960s and the late 1980s, began not with an attack by the left-wing Red Brigades, the most prominent radicals of the period, but with the Piazza Fontana bombing in Milan carried out by Ordine Nuovo, a neofascist group, which killed seventeen people and injured eighty-eight. An offshoot of that group perpetrated the era’s most lethal attack, the 1980 bombing at the Bologna train station, in which eighty-five people died and two hundred were hurt. More recently, due in significant part to the accelerating influx of mainly Muslim refugees from the Middle East, racist and anti-immigrant attitudes have spread throughout the continent, notably in France, Germany, Italy, Scandinavia, and the United Kingdom, as well as in Hungary and Poland.

While Breivik was assessed to be mentally disturbed (though legally sane) and to have acted alone despite his claims of networked support, his militantly anti-Islamic and anti-immigrant beliefs were part of a trend. Loyalist paramilitaries in Northern Ireland have developed more pronounced right-wing attitudes, some committing racist and anti-immigrant attacks. On the British mainland, former British National Party members have joined more extreme groups such as National Action, and several have committed or planned terrorist attacks or been convicted of terrorism-related charges. The far-right extremist Thomas Mair brutally murdered the MP Jo Cox in 2016, and UK authorities have thwarted several right-wing terrorist plots.

The xenophobic National Socialist Underground was formed in Germany in the late 1990s, and killed ten people—most with Turkish backgrounds—between 2000 and 2007. In 2014 a thirty-member racist, anti-Semitic, and anti-Muslim group known as the Oldschool Society arose in Germany; it accumulated weapons and planned to attack a refugee shelter before its leaders were arrested in 2017.21 In October, on Yom Kippur, a heavily armed man spewing anti-Semitic hatred tried to storm a synagogue in Halle, Germany; finding it locked, he killed two bystanders. There has been right-wing terrorist activity in France and Sweden as well, and it is beginning to appear in Poland. Yet counterterrorism priorities in Europe have been similar to those in the United States, privileging Islamist threats over right-wing ones.22

Right-wing extremism is unlikely to yield a transnational organization as powerful as al-Qaeda or ISIS, but the dynamics of the two movements appear to be similar. Forced to decentralize after September 11, al-Qaeda encouraged self-initiated, homegrown terrorism, and ISIS has broadly followed this pattern. Thus jihadism became more localized and more like right-wing terrorism. Both forms are crucially, and ominously, unlike the ethnonationalist terrorism of the IRA or ETA. Ideological groups seek to force sweeping and pervasive societal and political transformation, whereas ethnonationalist groups have well-defined political aims, such as a change in sovereignty or the establishment of an independent state. These tend to make ethnonationalist terrorists more susceptible to political persuasion or compromise. They are also more discriminating in their targeting, focusing on state security forces and occasionally economic interests, so as to preserve the possibility of negotiation. Terrorists moved by apocalyptic scenarios, on the other hand, are interested in collective punishment and attack entire categories of people, such as ethnic minorities or immigrants. Thus right-wing terrorists, like the jihadist kind, are more difficult to mollify by nonviolent political means. They are no more amenable to anything like a Good Friday Agreement than al-Qaeda or ISIS is.

In the short term, only vigorous, proactive law enforcement and intelligence gathering can contain their threat. The September 11 attacks spurred robust transatlantic cooperation on jihadist terrorism, and that cooperation has since evolved and adjusted nimbly to changes in threat perceptions and patterns. There are no major institutional, bureaucratic, or operational reasons that the partnerships and modes of cooperation painstakingly developed since September 11 to deal with jihadist terrorism could not be readily applied to right-wing terrorism.

The political mainstreaming of xenophobic nationalism in the United States and Europe, however, could become a formidable political impediment. It is conceivable that Trump, like Steve Bannon, his former chief strategist, could find common cause with far-right European political forces such as the British National Party, France’s National Rally, and the Alternative für Deutschland against the left in general and the European Union—an important US counterterrorism partner—in particular.23 Richard Grenell, the US ambassador to Germany and an unabashed Trump loyalist, said in a Breitbart News interview in June 2018 that he wanted to “empower” the right in Europe.24 Many extreme British nationalists consider the US president a role model, and he reciprocated their support in late 2017 by sharing Islamophobic tweets from Jayda Fransen, the deputy leader of the far-right UK group Britain First.25

These points are hardly lost on American law enforcement and intelligence professionals. The Justice Department has conceded that it has had a “blind spot” with regard to domestic terrorism and hate crimes, and that both state and local authorities are lax about reporting them.26 The result is that American law enforcement and intelligence agencies are underprepared to counter right-wing extremism. In May the FBI for the first time identified right-wing conspiracy theories as a domestic threat. In the bureau’s judgment, such theories “very likely will emerge, spread, and evolve in the modern information marketplace, occasionally driving both groups and individual extremists to carry out criminal or violent acts,” and the FBI warns that they will probably increase during the 2020 election cycle.27 In congressional testimony in May, FBI Assistant Director Michael C. McGarrity acknowledged that “through the Internet, violent extremists around the world have access to our local communities to target and recruit…like-minded individuals and spread their messages of hate on a global scale.”

Yet the Trump administration’s consistent downplaying of domestic right-wing extremism, and at times its implicit apologism for violent right-wing impulses, have provoked concerns that it will neither admit the severity of the threat nor provide federal agencies the resources and political support they need to neutralize it. Indeed, Trump has at times cast law enforcement and intelligence agencies as devious elements of a “deep state.”28 Testifying before Congress in June, Elizabeth Neumann, assistant secretary of threat prevention and security policy at the Department of Homeland Security, admitted that “we’re not doing enough,” and confirmed that the Trump administration had not sought to renew $10 million in grant funding to prevent terrorism and in fact had reduced the budget of the DHS terrorism prevention office from $21 million to $3 million.

Some lawmakers have recognized the peril. Bills proposed in the House of Representatives and the Senate would place domestic terrorism on a substantially equal footing with international terrorism, make materially supporting it a crime, and give federal agencies more potent tools for preventing terrorist attacks by facilitating their intervention at the point of conspiracy rather than an imminent or completed act—in counterterrorism parlance, well “left of boom.”29 In September the Department of Homeland Security released a revised counterterrorism strategy that accords the same attention to domestic right-wing extremist groups as to foreign jihadist organizations, though it does not have the force of law.30 The New York City Police Department—which fields by far the most capable and experienced local counterterrorism force in the country, and probably the world—has been alert to domestic terrorist threats for years, understands that treating them differently from foreign terrorist threats (which New York State law does not) is counterproductive, and decries the minimization of domestic threats in the federal statutory scheme.31

The private sector is also beginning to take action. After the El Paso killings, the Internet infrastructure company Cloudfare shut down the website 8chan—the most popular and extreme of those visited and used by right-wing militants, on which terrorists had announced the attacks in Christchurch and El Paso in advance—at the urging of its founder, Fredrick Brennan, who had originally created it as a “free-speech-friendly” site. More publicly, Obama departed from his policy of noninterference in public life and exhorted Americans to “soundly reject language coming out of the mouths of any of our leaders that feeds a climate of fear and hatred or normalizes racist sentiments.”32 The question is whether congressional action, local vigilance, private-sector responses, and public outcry can overcome Trump’s resistance to impeding a movement that supports him.

Timothy McVeigh seems to have been the prototype of the “leaderless resistance” operator that Beam and Pierce, the foundational ideologues of today’s white power movement, conceptualized in the 1980s as a means of rendering it operationally invisible and all the more effective. Tarrant and Crusius epitomize it. In their planning and execution, they were self-starters. Yet their manifestos indicate that their conduct was networked as opposed to random, ideologically grounded, and designed to reinforce conspiracy thinking, such as the replacement theory, that drives a potentially borderless right-wing movement and gains recruits for it.33 It would appear that the second new global terrorism challenge in twenty years is now upon us—and that President Trump bears at least some responsibility for encouraging it.

—October 24, 2019

This Issue

November 21, 2019

The Defeat of General Mattis

The Muse at Her Easel

Lessons in Survival

-

1

See Peter Baker and Michael D. Shear, “El Paso Shooting Suspect’s Manifesto Echoes Trump’s Language,” The New York Times, August 4, 2019; Jeremy W. Peters, Michael M. Grynbaum, Keith Collins, Rich Harris, and Rumsey Taylor, “How the El Paso Killer Echoed the Incendiary Words of Conservative Media Stars,” The New York Times, August 11, 2019. ↩

-

2

See David Neiwert, “

Right-Wing Extremists Are Already Threatening Violence Over a Democratic House,” The Washington Post, November 16, 2018. See also Chip Berlet, “Heroes Know Which Villains to Kill: How Coded Rhetoric Incites Scripted Violence” in Mathew Feldman and Paul Jackson, editors, Doublespeak: The Rhetoric of the Far Right Since 1945 (Stuttgart, Germany: ibidem, 2014); Michelle Chen, “Donald Trump’s Rise Has Coincided With an Explosion of Hate Groups,” The Nation, March 24, 2017; and Kevin Roose and Ali Winston, “Far-Right Internet Groups Listen for Trump’s Approval, and Often Hear It,” The New York Times, November 4, 2018. ↩ -

3

See Jonathan Chait, “Trump Isn’t Inciting Violence by Mistake, But on Purpose. He Just Told Us,” New York, November 5, 2018; “Trump Gives Q Sign at Indiana Rally,” YouTube, November 5, 2018. ↩

-

4

William Saletan, “Radical Right-Wing Terrorism,” Slate, October 31, 2018. ↩

-

5

Wesley Lowery, Kimberly Kindy and Andrew Ba Tran, “In the United States, Right-Wing Violence Is on the Rise,” The Washington Post, November 25, 2018. ↩

-

6

Devlin Barrett, “Hate Crimes Rose 17 Percent Last Year, According to FBI Data,” The Washington Post, November 13, 2018. ↩

-

7

“Confronting White Supremacy (Part II): Adequacy of the Federal Response,” press release from the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, June 4, 2019. ↩

-

8

“Executive Order 13780: Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States, Initial Section 11 Report,” US Department of Homeland Security and US Department of Justice, January 2018 ↩

-

9

Ellen Nakashima, “Justice Dept. Admits Error But Won’t Correct Report Linking Terrorism to Immigration,” The Washington Post, January 3, 2019. ↩

-

10

See Kathleen Belew, Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America (Harvard University Press, 2018). ↩

-

11

See Kathleen Belew, Bring the War Home, chapter 9. ↩

-

12

See Janet Reitman, “U.S. Law Enforcement Failed to See the Threat of White Nationalism. Now They Don’t Know How to Stop It,” The New York Times Magazine, November 3, 2018. ↩

-

13

Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are (HarperCollins, 2017). ↩

-

14

Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, “The Data of Hate,” The New York Times, July 12, 2014. ↩

-

15

See, for instance, Ben Wofford, “The GOP Shut Down a Program that Might Have Prevented Dallas and Baton Rouge,” Politico, July 24, 2016. ↩

-

16

White Supremacy Extremism: The Transnational Rise of the Violent White Supremacist Movement, The Soufan Center, September 2019. ↩

-

17

Tim Arango, Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs, and Katie Benner, “Minutes Before El Paso Killing, Hate-Filled Manifesto Appears Online,” The New York Times, August 3, 2019. ↩

-

18

See David D. Kirkpatrick, “Massacre Suspect Traveled the World but Lived on the Internet,” The New York Times, March 15, 2019. ↩

-

19

Mary B. McCord, “Armed Militias Are Taking Trump’s Civil War Tweets Seriously,” Lawfare, October 2, 2019. ↩

-

20

See Clifford Bob, The Global Right Wing and the Clash of World Politics (Cambridge University Press, 2012); Manuela Caiani, “The Transnationalization of the Extreme Right and the Use of the Internet,” International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, Vol. 39, No. 4, November 2014. ↩

-

21

“Four Jailed in Germany for Forming Far-Right Terrorist Group,” The Guardian, March 15, 2017. ↩

-

22

See, for example, David Bond and Guy Chazan, “Rightwing Terror in Europe Draws Fuel from Populism and Xenophobia,” Financial Times, October 9, 2018. ↩

-

23

See Susan B. Glasser, “How Trump Made War on Angela Merkel and Europe,” The New Yorker, December 24 and 31, 2018. ↩

-

24

Rick Noack, “U.S. Ambassador to Germany Richard Grenell Suggests He Wants to ‘Empower’ the Right,” The Washington Post, June 4, 2018. ↩

-

25

See Liz Goodwin, “For the UK’s Nationalists, President Trump is a ‘Role Model’,” The Boston Globe, November 10, 2018; Lizzie Dearden, “Donald Trump Retweets Britain First Deputy Leader’s Islamophobic Posts,” The Independent, November 29, 2017. ↩

-

26

Janet Reitman, “U.S. Law Enforcement Failed to See the Threat of White Nationalism,” The New York Times Magazine, November 3, 2018. ↩

-

27

Jana Winter, “Exclusive: FBI Document Warns Conspiracy Theories Are a New Domestic Terrorism Threat,” Yahoo News, August 1, 2019. ↩

-

28

See, for example, Natasha Bertrand, “The Chilling Effect of Trump’s War on the FBI,” The Atlantic, May 25, 2018. ↩

-

29

Barbara McQuade, “Proposed Bills Would Help Combat Domestic Terrorism,” Lawfare, August 20, 2019. ↩

-

30

US Department of Homeland Security, Strategic Framework for Countering Terrorism and Targeted Violence, September 2019. ↩

-

31

See Ravi Satkalmi and John Miller, “We Work for the N.Y.P.D. This Is What We’ve Learned About Terrorism,” The New York Times, September 11, 2019. ↩

-

32

Quoted in, for instance, Felicia Sonmez, “In the Wake of El Paso Shooting, Obama Calls on Country to Reject Words ‘of Any of Our Leaders’ that Feed Fear and Hatred,” The Washington Post, August 5, 2019. ↩

-

33

See Kathleen Belew, “The Right Way to Understand White Nationalist Terrorism,” The New York Times, August 4, 2019. ↩