People think the mafia is first and foremost violence, hit men, threats, extortion, and drug trafficking. But before all else, the mafia is language and symbols. Who doesn’t recall the opening scene of The Godfather, when Vito Corleone extends his hand to Bonasera, the Italian who has come to ask him a “favor,” and who reverently kisses the boss’s hand to ingratiate himself?

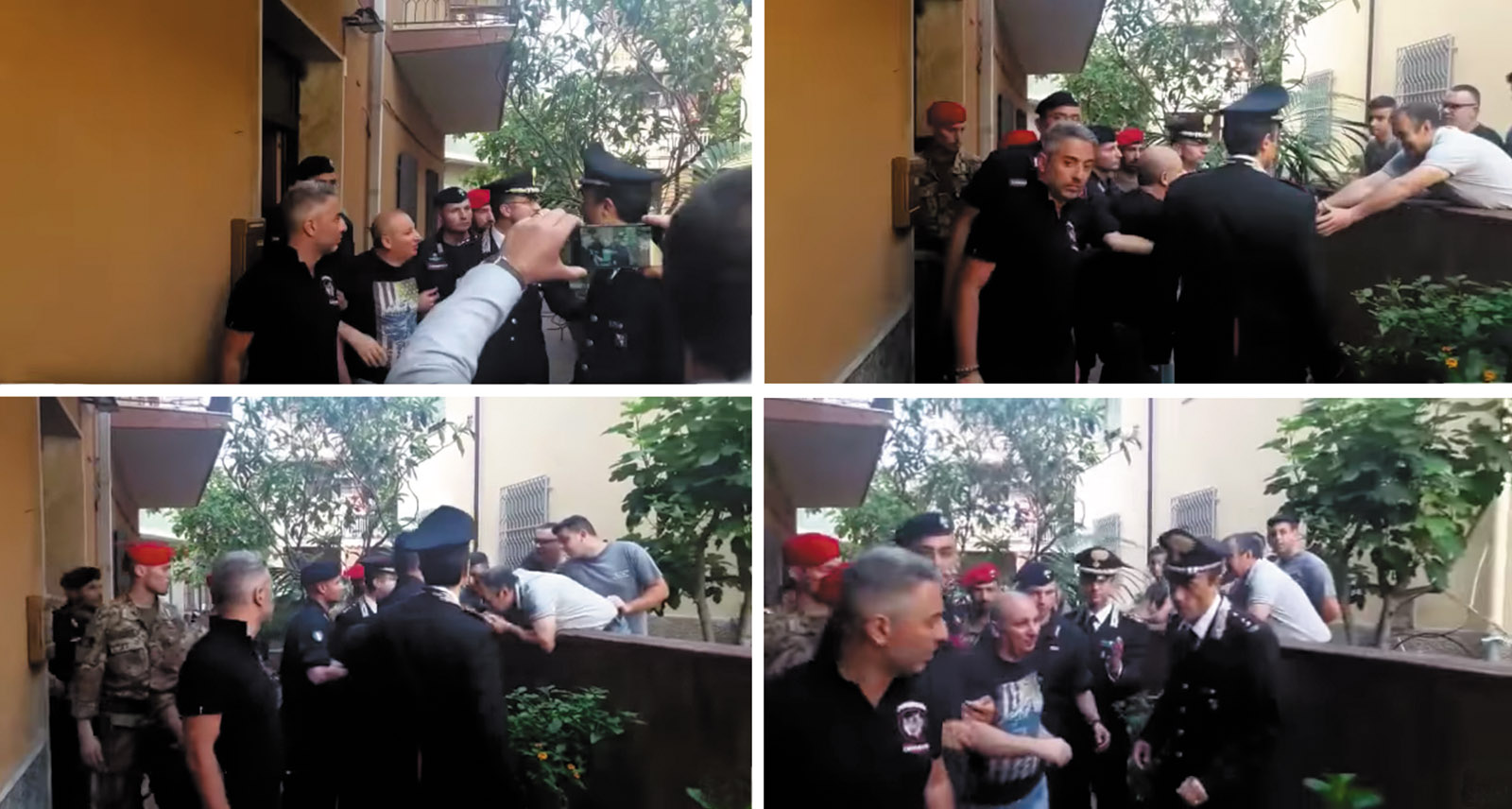

Such customs are not obsolete. In June 2017 Giuseppe “the Goat” Giorgi, a boss of the ’Ndrangheta (the Calabrian mafia) and one of Italy’s most dangerous criminals, was arrested. He had gone into hiding twenty-three years earlier, after being convicted of international drug trafficking and sentenced to twenty-eight years and nine months in prison. He was found above the fireplace of his family’s house, in a concealed space that opened by moving a stone in the floor, where he could hide in the event of searches while passing his fugitive days in the comfort of home. As the boss left the building under police escort, fellow villagers paid him tribute, one not only shaking his hand but kissing it.

Although hand-kissing is best known as a gallant way of greeting a lady, to kiss the knuckles of a man is a familiar gesture to anyone who, like me, grew up in southern Italy. It’s a tribute that has been adopted by the mafia, but its origin is quite different: this kiss was first bestowed upon the hands of Christ, from which miracles flowed. The custom spread to popes, cardinals, and priests, in whose hands the miracle of the host was renewed, and from there to the sovereign, who ruled by divine right. It’s a gesture that indicates not only respect but submission to someone whose authority is recognized. Every king, viceroy, general—and in more recent times certain mayors and local politicians—who have governed in southern Italy have received a kiss on the hand from citizens offering submission in exchange for protection.

That’s the idea behind the kissing of a mafia boss’s hand, which has the power to dole out life or death—or bread, when the state can’t. (The south has the highest unemployment rate in Italy, and often it’s the mafias that have jobs to offer, however illegal.) Kissing the hand of a boss, then, means submitting to him and acknowledging that he’s in charge, as does using the honorific “don” (derived from the Latin dominus—lord, master), which once indicated members of the aristocracy and confers on the boss a noble title he doesn’t actually possess.

The kissing of Giuseppe Giorgi’s hand happened in San Luca, a little town of four thousand that clings to the Aspromonte massif in Calabria. For the ’Ndrangheta, San Luca is more than a capital; they call it “la Mamma,” because it’s where everything originates. Like a mother, San Luca makes the rules, metes out the punishments, and grants rewards. Every ’Ndrangheta clan in the world answers to “la Mamma.” For more than a century, during San Luca’s festival of the Madonna di Polsi—also known as Our Lady of the Mountain, to whom the ’Ndranghetisti, like most Calabrians, are much devoted—an annual summit has been held for the bosses of all the local ’Ndrangheta cells scattered throughout Italy and the world. (With some 50,000 associates, the ’Ndrangheta is the only Italian mafia with a presence on all six inhabited continents.) A few steps from the entrance to the San Luca sanctuary stands the ’Ndrangheta’s symbol of symbols: the Tree of Knowledge, an old chestnut with a hollow trunk whose parts—trunk, branches, twigs, flowers, and leaves—symbolize the ’Ndrangheta hierarchy, from the highest leader to the traitor, represented by the fallen leaf rotting on the ground.

During the 2009 festival, law enforcement managed to record the ’Ndrangheta summit with cameras hidden outside the sanctuary. Circling a statue of the Madonna like devout pilgrims, the bosses were not reciting prayers but rather discussing positions that had been or would be filled and rules that needed to be followed in order to keep their organization, now so extensive, united under the control of San Luca. Whenever the authorities have discovered an ’Ndrangheta associate’s hideout, they’ve also found a figurine or an image of the Madonna di Polsi.

Religion is a constant point of reference for mafia organizations, and it is no mere cultural relic but a spiritual force. The bosses often consider their actions as a kind of Calvary: they take on the burden of sin for the good of the community over which they rule. The clan that pursues its illicit activity for the sake of its associates believes it has respected and followed Christian values. Even the Fifth Commandment may be suspended, the bosses reason, when murder serves a higher purpose, namely the safeguarding of the clan; in such cases, killing will be understood and forgiven by Christ by virtue of its necessity.

Advertisement

When, in San Luca in February 2008, police ransacked the enormous family residence of the fugitive ’Ndrangheta boss Antonio Pelle, they didn’t find him, but they did find three hidden bunkers. In one, on a small altar-like table, they found a figurine of the Madonna di Polsi along with several other icons, including prayer cards of Saint Michael the Archangel, considered the patron saint of the ’Ndrangheta. It was there, according to investigators, that Pelle inducted new associates into the organization. The prayer cards of Saint Michael the Archangel are used for the blood oath, the characteristic ritual of this criminal baptism: a finger is pierced with a needle or the base of the palm cut with a sharp knife, and a drop of blood made to fall onto the prayer card, which is then set on fire and partially burned. The meaning of this ritual is underscored by the words pronounced by the presiding boss: “As fire burns this image, so too will you burn if you taint yourself with dishonor.”

In 2007, in Duisburg, Germany, as they left a restaurant after a birthday party, six people linked to the Pelle-Vottari clan were massacred by the rival Nirta-Strangio clan—part of a ’Ndrangheta feud that had lasted for sixteen years. A charred Saint Michael the Archangel prayer card was found in the pocket of one of the victims, which quickly led investigators to believe that the restaurant in question had hosted that evening not only a birthday party but an initiation ceremony as well. (Inside the restaurant they found a statue of Saint Michael and, in a windowless back room, an image of the Madonna di Polsi, further signs that it was a ’Ndrangheta massacre.) But why Michael—who is not only the warrior-saint who leads the victorious battle against the devil in the Book of Revelation but also the patron saint of police? Because Michael is always portrayed with a balance and a sword, symbols of justice and respect for the laws, which for the ’Ndrangheta are not the laws of the state but the rules of their crime syndicate. In a ’Ndrangheta ritual, it is said of Michael that “with the sword he defends and with the balance weighs the honor of the Society.” To swear an oath on him, then, signifies complete submission to the syndicate’s codes.

The respect for these rules allows the ’Ndrangheta to survive and thrive in an underworld that is by definition lawless. Above all, these rules are what allow the organization to replicate its original form anywhere in the world, no matter how far from Calabria. In 1975, in an attic in the town of Stefanaconi, in the Calabrian province of Vibo Valentia, a document was discovered that contained the formulas for ’Ndrangheta rituals, from the initiation of the Youth of Honor (the first rank received on becoming an associate of the organization) to the “baptism of the local” (that is, the purification of a meeting place) to the opening ritual of a meeting between bosses. Of all the mafias, the ’Ndrangheta is the richest in codes and symbols, the meanings of which often remain obscure even to the affiliates themselves, but whose observance is not questioned.

In ’Ndrangheta ceremonies and meetings, for example, participants have always arranged themselves in a horseshoe shape, which can’t be broken until the person in charge declares the horseshoe “unformed” and the meeting therefore adjourned. No one has been able to fathom the reasons for this arrangement; perhaps it was simply adopted because it was thought to bring good luck. Yet today, from Calabria to Germany, from Australia to Canada, whenever a ’Ndrangheta group holds an official meeting, they still gather in the shape of a horseshoe. In October 2009, in the Paderno Dugnano suburb of Milan, in a social club that happens to bear the names of the two most important judges assassinated by the Cosa Nostra (Falcone and Borsellino), hidden police cameras captured a summit of the bosses of the ’Ndrangheta cells of Lombardy, the most modernized region in Italy and one of the most affluent in all Europe. And yet the first thing the bosses did on entering was to arrange the tables and chairs in the traditional horseshoe shape, as the ’Ndrangheta code requires.

’Ndrangheta rites also invoke ancient nature-related symbols, such as the moon and stars, as well as national heroes, such as patriots or generals who helped Italy achieve independence and whom the members consider their precursors: “In the name of Garibaldi, Mazzini, and La Marmora, with words of humility I create the Holy Society.” The ’Ndrangheta has appropriated religious rituals, mythological symbols, patriots, and even saints, much as it has taken possession of certain words, completely changing their meaning—honor, family, mamma—and in so doing has created around itself an aura of mystery and wonder that makes it attractive in the eyes of new initiates, especially the youngest. Symbols and codes serve to create a sense of belonging and to hand down an identity so powerful that its members are even willing to die for the organization.

Advertisement

Thanks to this symbolic inheritance, they don’t see themselves as simple criminals or gangsters but rather as part of a tradition—a criminal one, but also a noble and ancient one. According to the legend that they themselves have helped disseminate, Italian mafias descend directly from Osso, Mastrosso, and Carcagnosso, three brave Spanish knights and brothers who were members of the Garduña, a Toledo secret society. Around 1412 they fled Spain after avenging with blood the honor of their sister, who had been violated by an arrogant nobleman.

As legend has it, they sailed to Favignana, an island off the coast of Sicily, in whose caves they hid for nearly thirty years. During that time, they established “tables of law” for a secret society similar to the one they had left behind. When they emerged, the three knights began proselytizing those laws: Osso stopped in Sicily and founded Cosa Nostra; Mastrosso went to Calabria and founded the ’Ndrangheta; and Carcagnosso traveled to Naples and founded the Camorra. This is the origin myth of the three major Italian crime syndicates. They think of themselves not merely as drug traffickers or loan sharks or murderers but as noble knights of evil who revive and respect the codes and rites that their fearless forefathers passed down to them.

A frequent part of mafia rituals is the kiss. After a Youth of Honor has been baptized, he makes the rounds of the other associates, kissing each twice on the cheeks, except for the capo società (the highest-ranking associate), whom he kisses three times. Kissing the cheeks of the other associates symbolizes the relationship among equals that from that point forward the Youth of Honor will have with the other members of the clan. The kiss, then, becomes the seal on the oath of eternal loyalty to the new family he is now joining. According to mafia grammar, however, there are different types of kisses, each with a different meaning.

In Cosa Nostra, for example, a kiss on the forehead is given to ratify the choice of a new boss. In 2015 the old Palermo boss Salvatore Profeta was caught on law enforcement cameras kissing the forehead of Giuseppe Greco, the new godfather about to become the district boss in the imminent “elections.” With that kiss, he gave his placet, his public support of the new boss’s candidacy. In the Camorra—the Neapolitan mafia—several associates have been observed in recent times being kissed on the lips immediately following their arrests. Often it’s another man—a son, a brother, a brother-in-law, a right-hand man—kissing the man who has been arrested, and that kiss seals his lips and pledges to the world that he won’t talk, won’t turn state’s witness. The person giving the kiss is the guarantor of the pledge: were the prisoner to talk, the first to pay the price would be the person (always someone dear to the prisoner) who had kissed him.

The symbols can change their meaning over time. In the past, for example, if a boss kissed you on the mouth, it signified a death sentence. The Camorra, among all the mafias, is the one whose codes and behaviors have evolved the most. One has only to think of the symbol that marks the paranze, the new clans of young Camorristi who dominate downtown Naples today, and that would have been unthinkable fifteen to twenty years ago: the tattoo. In the past, certain members of the ’Ndrangheta got bullu tattoos, three black dots between the thumb and index finger. For some they symbolized the legendary knights Osso, Mastrosso, and Carcagnosso; for others they indicated the member’s rank. Members of the Sacra Corona Unita, a criminal organization based in Apulia, used to get rose tattoos on their right shoulder or arm. Other mafiosi wore wind-rose tattoos that meant “wherever you go, omertà goes with you,” or eyes on their backs to show they could see even what was done behind them. But these were nothing like the showy and ubiquitous tattoos of the Salvadoran maras or the Russian mafias, for whom tattoos have always been a clear sign of their link to a criminal group and their distance from the rest of society.

In recent years, however, young Camorristi have begun tattooing their forearms, necks, and chests with the initials of their criminal family, with the names of their clan bosses, and, above all, with numbers that, after much investigation, were found to correspond to letters of the alphabet, specifically the initials of the clan they belong to. The number 17 stands for the S of the Sibillo clan, active in Naples’s Forcella neighborhood; 2 stands for the B of their rivals, the Buonerba clan. To decipher 32, investigators had to turn to the smorfia (a sort of Neapolitan cabala that translates dream images into lotto numbers), in which 32 corresponds to the eel, which happens to be the nickname of the Lo Russo clan. Certain members of the Sibillo clan must also have been winking at the smorfia when, finding themselves represented alphabetically by the number 17—which corresponds to bad luck in the smorfia—decided to tattoo that number amid flames, as if to say, “Let bad luck burn! It doesn’t scare us!” These numbers are found today in plain sight on the bodies of Camorristi who are barely past puberty (like their Latin American counterparts, they flaunt their criminal ties with pride) and on the alley walls of Naples, where they mark turf.

But don’t these symbols clearly expose mafia members to investigators? Not always, because the symbols are chosen so as not to offer any objective or irrefutable proof of their meaning, and thus they can always be contested by defense attorneys at trials. The mafia has a great talent for being visible while remaining invisible to the law. Mafiosi often even speak publicly—bosses of various organizations have granted TV interviews or have written public letters—without making themselves legally vulnerable.

To understand what a mafia boss says, outsiders must do more than listen to his words; they must decipher them, decode them, and the keys in their possession are often not enough to make the meaning clear. This obscurity is one of the mafia’s great strengths and has made it ultramodern. Camorristi today communicate easily via social media, often with public profiles, so that any message can easily reach its intended recipient—no need for handwritten notes, messengers, or intermediaries. Just post it online.

Mafias communicate even through a grammar of death. You shoot someone in the back of the neck to show dominance, to affirm your own triumph and humiliate your defeated rival. You shoot in the face someone accused of betraying his own family, of doing something shameful—someone who has “lost face.” Someone who misappropriates money has his right hand cut off, since that’s the hand typically used to take money. Someone who shows disrespect gets shot in the legs—though that may not be enough for more serious affronts, such as the one committed by Anna Barbera, mother of Umberto Ippolito, a youth killed in 1994 by the Gionta clan a few days before he was to testify against the Camorra. At the trial of his killers, his mother spat in their faces as a sign of contempt, a gesture the bosses couldn’t let pass without sending a message that no one could disrespect them. A few weeks later, the clan’s hit men, on a motor scooter, approached the woman’s car as she was returning from the market, killing her with two shots to the head. The mafia’s humiliation had been quickly avenged and the hierarchies of power restored.

For crimes of passion, you may be shot in the genitals, or even castrated, as happened in 1982 to Pino Marchese, a singer from Palermo who committed the unforgivable sin of having an affair with the sister of a Cosa Nostra boss, Giuseppe Lucchese. The woman was married, and mafia organizations consider marriage and family inviolable; they had to punish Marchese to restore their honor. His bound body was found in the trunk of a car, his genitals in his mouth: for the mafiosi, his sin was his last song. Later, the woman was also killed; by being unfaithful she had violated the rules of Cosa Nostra and stained the family’s honor.

Widows, like married women, are also untouchable: if you’re the widow of a Camorrista, you can remarry only with the consent of your male sons and only after respecting a seven-year period of mourning. According to ancient peasant beliefs, seven years was how long it took a soul to reach the afterlife; you waited that long so the dead husband wouldn’t see his wife in the arms of another man. In practice, this delay helps ensure that widows don’t confide any secrets they might possess to new companions for at least seven years after the death of their husbands, thus offering the organization a little insurance. But it’s typical of mafias to find ancient mythological justifications for even their most awful rules.

Cosa Nostra used to punish traitors by “goat-tying” them: tying their wrists and ankles together behind their back, then looping the rope around their neck, so that eventually they strangle themselves to death—a brutal method that takes its name from the way young goats were immobilized during transport, and that has nearly disappeared. Though it seems merely a barbaric kind of torture today, goat-tying recalls the biblical ritual of the scapegoat: just as Jews, as penance, would sacrifice a goat at the temple to cleanse it of the sins with which they had burdened it, so the mafiosi would kill the traitor to cleanse the organization of the sin he had committed and restore order.

For criminal organizations, to kill is to celebrate a rite, a rite meant as a warning. A victim’s body can tell a detailed story about why he was killed. In September 2005, a few days after the arrest of the Camorra boss Paolo Di Lauro—caught by police in a hideout in his own neighborhood after three years at large—the body of Edoardo La Monica, from a family linked to the Di Lauro clan, was found in the road on the outskirts of Naples. Though definitive proof was lacking, the way he had been tortured seemed intended to communicate that his killing was connected to the boss’s arrest: his killers had removed the eyes and ears with which he had seen and heard where the boss was hiding, cut out the tongue with which he had blabbed about it, broken the wrists that moved the hands that according to the clan had accepted the police reward, and finally cut a cross into the lips that had broken faith, to seal them forever.

The Sicilian sociologist and journalist Michele Pantaleone, in his book Il sasso in bocca (The Stone in Mouth, 1970), details a number of particularly symbolic Cosa Nostra murders. In the 1950s, in Sicily, some corpses were found with prickly pear pads in their wallet pockets; the victims had taken Cosa Nostra money and so were punished by being pierced in the place where they had kept it. In the 1960s, in Chicago, a dime was found stuck with chewing gum to the shirt of a murdered man; he had informed (“dropped a dime”) on the mafia. A Sicilian farmer was found dead on a country road with his eyes gouged out and left in one of his hands; he had seen something he shouldn’t have. In the past, when a Cosa Nostra boss died, his coffin wouldn’t be closed until the new boss placed his hand on the dead man’s heart, so that his lifeblood could pass to the living man.

Mafias make use of such symbols because they are immediate, like slogans; they speak to everyone, and for a long time. And to help ensure that their deeds will endure, clans often choose to kill on holidays: Christmas, or a victim’s birthday or name-day (still a very special occasion in many parts of southern Italy). That way, every year, like clockwork, on a day that ought to be joyful, the wound is reopened. Those anniversaries will forever be darkened, made grievous not only by the loss but also by the cruel affront.

The Italian-American Cosa Nostra has largely inherited the symbols and value system of the Italian mafias, including the grammar of death. Joe Pistone, the FBI agent who between 1975 and 1981 infiltrated the New York mafia under the name Donnie Brasco, explained that the different ways of killing were meant to send different kinds of messages. If a person was suspected of being an informant, his killers would leave a canary in his mouth for having “sung.” “Sonny Black” Napolitano, the boss who was Brasco’s mentor in the organization, had his hands cut off for the sin of introducing an undercover agent to top mafia bosses; the handshake is the gesture of introductions. In remote villages in the Sicilian countryside and in the heart of New York City, people were killing—and dying—in the same ways, because it is in traditions and in symbols that mafiosi see themselves, find themselves, and continually reaffirm their own criminal choices.

—Translated from the Italian by Geoffrey Brock

This Issue

December 19, 2019

No More Nice Dems

What Were Dinosaurs For?

The Master’s Master