Mourning becomes Joe Biden. “I have found over the years,” he writes in his recent best-selling memoir Promise Me, Dad, “that, although it brought back my own vivid memories of sad times, my presence almost always brought some solace to people who have suffered sudden and unexpected loss…. When I talk to people in mourning, they know I speak from experience.” The most moving thing in that book is not even Biden’s restrained and heartbreaking account of the slow death of his beloved son Beau. It is the two brief appearances of Wei Tang Liu, whose son, Wenjian Liu, was one of two police officers murdered in New York City on the Saturday before Christmas 2014. Biden visited the family home in Brooklyn to pay his respects.

The father, an immigrant from China, had little English, but Biden picked up on his need for physical intimacy, for the consolation of touch: “Occasionally he would lean into me so that his shoulder touched my arm…. I did not pull away, but leaned in so that he could feel me there.” When Biden finally made to leave, Liu walked outside with him and embraced him in front of the line of policemen standing watch. “He held on to me tightly, for a long time, as if he could not bear to let me go.” Five months later, when Beau was dead, Biden was leaving the public wake at St. Anthony’s church in his hometown of Wilmington, Delaware. He saw, in the long line of mourners, Wei Tang Liu. Neither man spoke to the other: “He just walked up and gave me a hug. It meant so much to me to be in the embrace of somebody who understood. He held on to me, silently, and wouldn’t let go.”

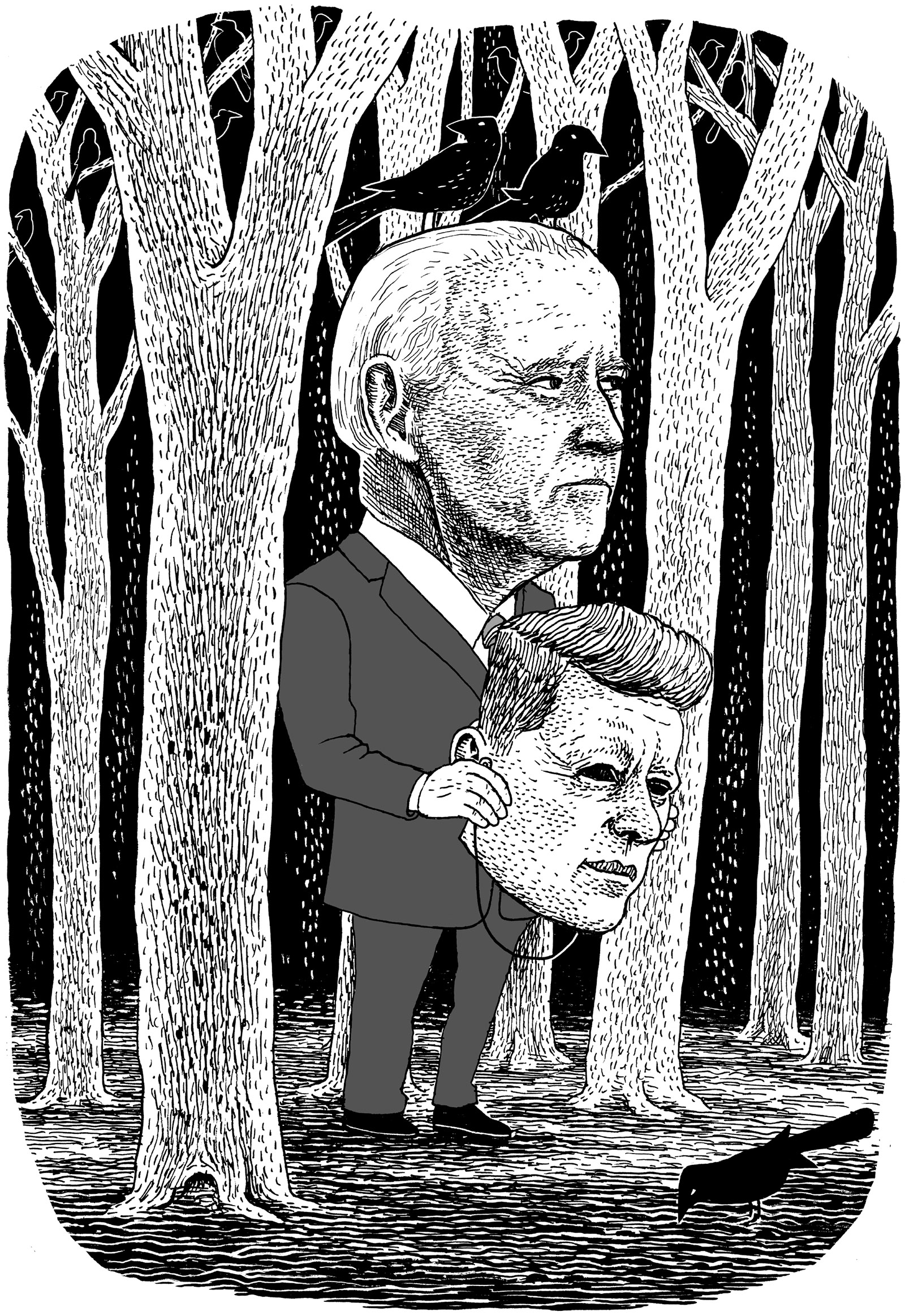

Joe Biden is the most gothic figure in American politics. He is haunted by death, not just by the private tragedies his family has endured, but by a larger and more public sense of loss. Richard Ben Cramer, in his classic account of the 1988 presidential primaries, What It Takes, wrote how even then it was a journalistic cliché to define Biden by the terrible car crash that killed his first wife, Neilia, and their daughter, Naomi (and injured Beau and his brother, Hunter), in 1972, shortly after Biden was elected to the Senate at the age of twenty-nine. Cramer refers to the “type that fell out of the machine every time they used Biden’s name: ‘…whose life was touched by personal tragedy…’ Joe Biden (D-Del., T.B.P.T.).”

Even now, as Hunter Biden’s name is threaded through Donald Trump’s impeachment hearings, there is a ghost behind it: Hunter is Neilia’s maiden name. Trump’s preoccupation with Hunter’s presence on the board of the Ukrainian energy company Burisma hinges on a reality that is certainly worthy of scrutiny: Joe Biden was, as he recounts in some detail in Promise Me, Dad, deeply involved in the Obama administration’s relations with Ukraine, and it seems implausible that Hunter’s position with Burisma was merely coincidental. But the frenzied inflation of this story, like so much that involves the Bidens, is freighted with both dread and grief. The dread is Trump’s (arguably misplaced) fear of Biden as a competitor for the presidency in 2020, an anxiety that became a manic fixation that has led to his impeachment. The grief drives Biden’s fierce need to protect his living son, not just for himself, but for Hunter’s dead mother and brother.

Yet even if those horrible losses had not befallen his family, Biden would have a very public relationship to the dead. He is haunted by the murdered Kennedys. In his campaign speeches he has evoked the image of himself and his sister, Valerie, weeping openly as Robert Kennedy’s funeral train passed by. For the first decades of his political career, his pitch was essentially that these dead men could rise again through him. The speech that first made people talk of Biden as a potential presidential candidate was at the New Jersey Democratic Convention in Atlantic City in 1983, when he brought the house down with his evocation of the slain: “Just because our political heroes were murdered does not mean that the dream does not still live, buried deep in our broken hearts.” Biden recalled in his 2007 memoir Promises to Keep, “I remember the feeling in the room when I delivered that line; its effect on the crowd washed back at me as a physical sensation. I could see people in the audience crying.” He also realized that in channeling the dead, he allowed each listener to “fill in my words with his or her own meanings…. After all, each person has a little something different buried in a broken heart.”

Advertisement

Here was Biden the consoler and at the same time the ambitious politician, for what he really meant was that the Kennedys lived on in him. Biden’s biographer Jules Witcover writes of Biden in 1987, early in his campaign for the Democratic primaries, “Casting himself as the next young and rising John F. Kennedy, Irish Catholic Biden told the cheering Iowa Democratic faithful…‘I think 1988 is going to be about 1960.’”1 That, of course, was the year of JFK’s coming. Biden even repeated exactly JFK’s slogan, “Let’s get America moving again.” The ghost of the other dead Kennedy hovered around him too. Of the campaign managers who were trying to shape a grand story for Biden in 1988, Cramer writes:

It wasn’t that they wanted to make Joe into Robert Kennedy…it just happened that Robert Kennedy was important…to the time, to a whole generation. And that was the message: that a whole generation was lost, submerged, driven off from the struggle for a better world, twenty years ago, in ’68, bloody ’68, the Year of the Locust, and the Tet Offensive, the Chicago Convention, and Richard Nixon, and the murders of Martin Luther King and…Bobby KENNEDY! That was the whole fucking point!… That a whole generation had to come back now, that they had to wake up!

There is something eerie in this notion. Biden becomes not just the reembodiment of the dead Kennedys but a kind of political necromancer, calling forth an entire generation that has been wandering in a civic Hades, lost to the world of democratic engagement. He also becomes the man who can imaginatively reverse time, who can take us all back to 1960, back to the beginning of the story so that it can be told again without the blood-soaked pages.

The most important question, though, is what gave Biden the right to make this vast claim? It was not the authority of experience—I was there by the side of our murdered hero. In the two great mass movements of the 1960s, the campaigns against the Vietnam War and for civil rights, Joe Biden was conspicuously not there. There were large protests against the war in Wilmington—he does not seem to have attended any. College deferments saved him from any danger of being drafted for Vietnam.

In 1968 and 1969 Wilmington was placed under military occupation by the Delaware National Guard for fully nine months after riots following King’s assassination. In Promises to Keep, Biden recalls passing “six-foot-tall uniformed white soldiers carrying rifles” on his way to work at a law office every day. He acknowledges that, in the black neighborhoods of East Wilmington, these white soldiers were “prowling” the streets and that “mothers were terrified that their children would make one bad mistake and end up dead.” But he then folds their terror into an anecdote about how he got to know black people for the first time while working as a lifeguard in a black district six years earlier. The extraordinary political event—an American city under military occupation—becomes an intimate tale of awakening sympathy.

This lack of personal involvement in the struggle did not stop Biden, when he was seeking national office, from inventing a civil rights past for himself. Cramer reported on his rhetoric in the primaries in 1988: “Joe was off on his life…how he started in the civil rights movement…remember?… The marches? Remember how that felt?… And they’re nodding in the crowd, and he’s got them, sure.” Even when his handlers warned him to stop saying this because it was not true, he couldn’t help himself: “Folks, when I started in public life, in the civil rights movement, we marched to change attitudes.” The plain fact, as Witcover notes, is that “he avoided street protest or anything else that smacked of civil disobedience.” He was a concerned observer of, not a participant in, the great dramas of the 1960s.

So how could Biden imagine himself as the reincarnation of the Kennedys? Those two words: Irish Catholic. His claim to that legacy is not experiential or particularly ideological. It is ethnic and religious. The Kennedys defined an Irish-American Catholic political identity—white (even in their case conspicuously privileged), yet by virtue of the grimness of Irish history and the outsider status of Catholics, supposedly not guilty of the grave crimes of racial oppression. Its promise was to act as the bridge across the great divide of US society, being mainstream enough to connect to the white majority but with a sufficient memory of past torment to connect also to the black minority. Its underlying appeal was to the very thing that Biden would come to embody—“a sense of the depth of their pain” rooted in “vivid memories of sad times.” This is what Biden chose when he defined himself as he has throughout his public career: “I see myself as an Irish Catholic.”2

Advertisement

And this was indeed a choice. Biden is not an Irish name—he recalled in Promises to Keep his Irish-American aunt, Gertie Blewitt, telling him: “Your father’s not a bad man. He’s just English.” Nor is his middle name, Robinette. The Robinettes, his paternal grandmother’s kin, traced their ancestry in America to a tract of land near Media, Pennsylvania, originally granted by William Penn. So Biden could have presented himself, had he chosen, as an all-American boy. Instead he identified with his mother’s ethnic ancestry, making himself, as he puts it in Promise Me, Dad, a “descendant of the Blewitts of County Mayo…and the Finnegans of County Louth, on a volatile little inlet of the Irish Sea.” Part of the attraction was undoubtedly the devout Catholicism that has been Biden’s great consolation. But another part was the great escape from American history and its burdens of guilt. Biden recalled the same aunt telling him about the notorious British irregulars sent to put down the Irish nationalist revolt in 1920:

I’d go upstairs and lie on the bed and she’d come and scratch my back and say, “Now you remember Joey about the Black and Tans don’t you?” She had never seen the Black and Tans, she had no notion of them, but she could recite chapter and verse about them. Obviously there were immigrants coming in who were able to talk about it and who had relatives back there. She was born in 1887. After she’d finish telling the stories I’d sit there or lie in bed and think at the slightest noise, “They’re coming up the stairs.”3

This is a fine description of vicarious oppression. Biden grew up in relatively prosperous middle-class American comfort and went to Archmere, a privileged fee-paying Catholic high school in Wilmington. Even as a national politician, he seems to have been largely shielded from anti-Catholic venom. But one of the advantages of being an Irish-American Catholic is that you can attach yourself to a history of oppression in Ireland and release yourself from white guilt in America. Your forefathers are sinned against, not sinning. As Biden put it in 1974, defending his opposition to busing in Wilmington, “I feel responsible for what the situation is today, for the sins of my own generation. And I’ll be damned if I feel responsible for what happened three hundred years ago.” By “what happened” it is clear that he meant slavery. How could the Irish be responsible for that?

Above all, though, being Irish Catholic created the possibility of reincarnating the Kennedys. Biden’s desire was there from his coming of age. He told Neilia that he would be a senator by the time he was thirty and then president of the United States. He achieved the first through sheer chutzpah, taking on the incumbent Republican, Cale Boggs, who had won seven straight elections and had held state and federal office for twenty-six years. Biden got the nomination because no serious Democrat even wanted to run against Boggs. But the Kennedy magic worked. And it is clear that Biden thought it might work all the way. Cramer reported on Biden’s fantasy project in the 1980s to buy a seventeen-acre plot and have his extended family all together in different houses:

Joe and Jill and the kids would take the big one, and then a guest house…it was a compound, it was…Hyannisport! He could see the goddam thing in Life magazine, he could just about lay out the photos right now…The Bidens. First Family.

And like the Kennedys, this First Family was to be dynastic. As Biden wrote in Promise Me, Dad, “I was pretty sure Beau could run for president some day and, with his brother’s help, he could win.” The reader is invited to imagine, through the evocation of the brotherly bond, that Hunter might then succeed Beau. The Irish Catholic dynasty of which the US was robbed by the murders of the Kennedys in the 1960s would return in the 1980s and last, perhaps, for decades.

But in gothic stories, dreams of the dead shade into nightmare. On the political level, the second part of the Biden plan—becoming president—has made him a revenant. Cramer, writing about Biden’s discussion of a run for the 1988 primaries, describes Jill Biden wondering, “What if Joe did break out and made a run for the finish, and came in…just short. Then they’d run again…and again. That was her nightmare: that he’d run, come close, and then it would never stop.” Her nightmare became real. Biden filled out papers for the New Hampshire primary of 1984, ran for the 1988 nomination, ran again for 2008, and is running yet again for 2020.

A major problem here is that Irish Catholicism, youth, and good looks were never enough to make Biden the heir to RFK. To return to that speech in Atlantic City in 1983, in which Biden invoked the murdered heroes, its appeal to unity is vastly blander than Kennedy’s insurgent effort to forge a real unity of purpose between the black and white working classes. Biden, like RFK, positioned himself as a figure who could transcend class, race, gender, and party, but this time in the name not of radical change but of a mere rhetorical figment. He urged Democrats to campaign “not as blacks or as whites; not as workers or professionals; not as rich or poor; not as men or women, not even as Democrats or Republicans. But as people of God in the service of the American dream.” The utter vacuity of the last sentence points not to a transcendence of divisions but to mere evasion of all questions of power, privilege, and systematic oppression.

There is something almost too ghoulishly spectral—more Halloween than haunting—in the way Biden’s most promising presidential bid, his first, was derailed by Robert Kennedy. Biden got into trouble when it was revealed that he had effectively plagiarized a speech by the then leader of the Labour Party in Britain, Neil Kinnock. But he might have weathered the storm, since he had actually credited Kinnock several times previously in using the same material. What destroyed him was the unearthing of an earlier speech in which he echoed, word-for-word but without attribution, a long passage in which RFK had attacked the idea of the “bottom line”: “That bottom line can tell us everything about our lives…except that which makes life worthwhile.” Adam Walinsky, who wrote the original speech, accused Biden of a “counterfeit of emotion.” Instead of being a reincarnation, Biden appeared as a grave robber.

Yet the one Kennedy trait no one can accuse Biden of faking is tragedy. And within this tragedy, there is the other side of the Irish Catholic dream. The shadowy twin of the striving for success is an almost Greek sense of the capriciousness of fate. The Kennedys’ dazzling success comes with a terrible toll of death. Biden, cruelly, endured the pain without ever quite matching the glamour of the ascent. He wears his dead son’s rosary beads around his wrist and says that litany of prayers in his dark moments. It culminates in a great cry of despair directed to the mother of the crucified Christ: “To thee do we cry, poor banished children of Eve. To thee do we send up our sighs, mourning and weeping in this valley of tears.” Biden has had to live much of the time in the valley of tears, and in this long sojourn his Irishness is about something more than vicarious oppression. It is a way of framing sorrow.

In Promise Me, Dad, Biden quotes one of the grand figures of Irish-American politics, Daniel Patrick Moynihan: “To fail to understand that life is going to knock you down is to fail to understand the Irishness of life.” So while an African-American choral group was chosen to play “joyful music” at Beau’s memorial service, Biden notes that there were also “bagpipers to add the mournful, plaintive wail of Irishness.” In his address at the service, Barack Obama quoted a line from a song by the Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh, in which mourning is as inevitable as the passing of seasons: “And I said, let grief be a fallen leaf at the dawning of the day.”

It scarcely matters here whether there’s much truth in the notion that the Irish have a particularly familiar relationship with grief. What does matter is that the “mournful, plaintive wail of Irishness” is the soundtrack for both the Kennedy and the Biden stories, in which triumph is always shadowed by calamity. There is in this structure of feeling no easy opposition of hubris and nemesis. There is just, as Obama said to Biden when Beau was dying, the awareness that “life is so difficult to discern”—difficult because it does not offer itself in the easy forms of the wonderful and the terrible but confuses the two by conjoining them as twins. The political manifestation of this awareness is not the upbeat rhetoric of the American Dream; it is a politics of empathy in which the leader shares the pain of the citizen. While Biden seems hollow when he deploys the former, he has been a forceful practitioner of the latter. “We had to speak for those who felt left behind,” he writes in Promise Me, Dad. “They had to know we got their despair.” Biden has always been better at getting despair than at giving concrete, programmatic form to hope.

With Biden, fellow feeling is literal—he feels you. He is astonishingly, overwhelmingly hands-on. He extended the backslapping of the old Irish pol into whole new areas of the body—hugging, embracing, rubbing. In his foreword to Steven Levingston’s engaging account of the Biden–Obama relationship, Barack and Joe, Michael Eric Dyson writes of the vice president’s “reinforcing his sublimely subordinate position by occasionally massaging the boss’s shoulders.” But Cramer noted Biden doing the same thing to an anonymous woman at a campaign stop in 1987: “Gently, but decidedly, he put his hands on her. In Council Bluffs, Iowa! He got both hands onto her shoulders, while he talked to the crowd over her head, like it was her and him, through thick and thin.” So not really a gesture of submission or of domination, perhaps, but a desperate hunger to connect, to touch and be touched, to both console and be consoled. “The act of consoling,” Biden writes, “had always made me feel a little better, and I was hungry to feel better.”

There is something religious in this laying-on of hands. It is an act of communion. But it is also profoundly problematic—and not just for the obvious reason that, in the Me Too era, touching is too apt to raise questions of gender, power, and consent that clearly did not occur to Biden in Council Bluffs or anywhere else. It too easily depoliticizes pain. To see how this can play out in practice, consider a phone call Biden made to Anita Hill in October 1991. Clarence Thomas had been nominated to the Supreme Court by George H.W. Bush. Biden, as chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, was in charge of the process. Hill had written, in confidence, an account of Thomas’s sexual harassment of her. Biden was calling her to invite her formally to testify at a hastily arranged public hearing. Hill was worried about whether she would be protected from verbal assault and whether witnesses who came forward to express similar concerns about Thomas would also be heard. Here is Hill’s account:

“The only mistake I made, in my view, is to not realize how much pressure you were under. I should have been more aware,” Senator Biden confessed over the telephone line. “…Aw kiddo I feel for you. I wish I weren’t the chairman, I’d come to be your lawyer,” he added when I told him I had not secured legal counsel. I fought the urge to respond as I furiously took notes of our conversation, hoping for some useful information. Little concrete information was forthcoming. As he closed the conversation, I could almost see him flashing his instant smile to convince both of us that the experience would be agreeable.4

“Aw kiddo I feel for you” is pure Biden. If he could have reached through the telephone, he would surely have massaged Hill’s shoulders. There is no reason to think he was disingenuous. The problem is that he felt for Clarence Thomas too. As Witcover puts it, “Joe seemed to be trying to convince both the judge and his female adversary that he was their friend.” After receiving Hill’s written allegations but before she testified, Biden went to the Senate floor to say that “for this senator, there is no question with respect to the nominee’s character…I believe there are certain things that are not an issue at all.” He then failed to call the two women who could corroborate Hill’s testimony, Rose Jourdain and Angela Wright, to appear before his committee. Feeling is not enough: there were great questions of gender and power and the nature of public deliberation at play in the Thomas hearings, and “aw kiddo” was a brutally inadequate answer to any of them.

This is not to deny the power or the sincerity of Biden’s empathy. It is real and rooted and fundamentally decent. It has at its core the baffled humility of the human helplessness in the face of death that makes life “so difficult to discern.” As an antidote to Donald Trump’s grotesquely inflated “greatness,” it has authentic force. It is a different, and much better, way of talking about distress, of making pain a shared thing rather than a motor of resentment. But can a politics of grief be adequate to a politics of grievance? Can it deal either with the real grievances of structural inequality or with the toxic self-pity that Trump has both fostered and embodied? Biden’s essential appeal as a candidate for 2020 is that he (not least being older, male, and white) is the only one who can heal a heartbroken and divided America. But he cannot embrace voters one by one. The US cannot be made whole again because it has never been whole. Biden’s core belief is that injustice is a failure of benevolence and effort: “There is nothing inherently wrong with the system; it’s up to each of us to do our part to make it work.” But division is real and profound and structural—it is not just a matter of feeling. The need is not to reconcile everyone to the balance of power but to alter that balance. Consolation is not social change. Solace is not enough.

When he was vice president, Biden became fixated on the digital clock outside his official residence in the Naval Observatory in Washington. As he recalls in Promise Me, Dad, “Red numbers glowed, ticking away in metronomic perfection…. This was the nation’s Precise Time, which was generated less than a hundred yards away, by the US Naval Observatory Master Clock.” The young Biden thought he could turn the clock back to begin again at 1960, but the Master Clock moves in one direction only, and as the decades pass they bring the realization that there will be no Precise Time for President Biden. As his limousine pulls out onto Massachusetts Avenue, he sees it in his mind’s eye: “The clock was behind us in a flash, out of sight, but still marking the time as it melted away.” The years melt away and the presidential dream recedes as Biden keeps striving toward it, driven by a sense of destiny that has become, over the years, less shining and more tragic. What began in bold hope is now tinged with despair—what else but the presidency could make sense of all his suffering?

But the Master Clock has moved too far forward. The Kennedys are too long dead. “Irish Catholic” no longer carries that old underdog voltage of resistance to oppression. The center of gravity of Irish-American politics now gathers around Trump: Mick Mulvaney, Kellyanne Conway, Brett Kavanaugh. A politics of white resentment has drowned out the plaintive wail of common sorrow. The valley of tears has been annexed as a bastion of privileged white, male suffering. Biden, who once promised to turn back time, is an increasingly poignant embodiment of its pitilessness.

This Issue

January 16, 2020

Is Trump Above the Law?

It Had to Be Her