If you’ve read Deborah Levy’s punchy memoir The Cost of Living (2018), you know about her string of pearls. At around the age of fifty, just as “life was supposed to be slowing down” for Levy, a South Africa–born writer based in England, her marriage falls apart. She sells her family house, moves with her daughters to an apartment building whose “communal corridors were covered in grey industrial plastic for three years after we moved in,” and subjects herself entirely to “the Republic of Writing and Children.” One day, lugging heavy grocery bags, Levy runs into a neighbor who has taken to scolding her for leaving her bicycle in the wrong parking lot. At that moment, the pearl necklace that Levy wears all the time—even to write in a dusty shed, even to go swimming—breaks, and the pearls scatter to the ground. “Oh dear,” the neighbor says. “Tuesday is not your day, is it?” Her unhappiness, Levy writes, was like Beckett’s definition of sorrow: “A thing you can keep adding to all your life…like a stamp or an egg collection.”

Levy has described her fascination with those pearls as stemming from Colette’s novel Cheri, which begins with a couple’s quarrel over a pearl necklace that the man believes would look better on him than on his lover. The reference is unsurprising. Levy’s deceivingly slim books are crammed with allusions to her literary progenitors: Colette, Simone de Beauvoir, Marguerite Duras, but also Louise Bourgeois, Claude Cahun, and Cindy Sherman. For Levy is, above all, a visual writer, heaping image upon tantalizing image. A naked woman floating—or is it drowning?—in a French Riviera swimming pool that is more marshy pond than tourist-blue. (You can practically hear the pulsing of the cicadas.) A chicken tumbling out of a grocery bag and flattened by the tires of an oncoming car, “like roadkill,” then roasted and devoured for dinner. A delicate young man caressing a neighbor’s poodle on a “turtle-green sofa,” a telephone ringing in the background while he’s thinking back to a lunch he had with a friend who, Levy writes, “was somehow lacking in feeling.”

Her three most recent novels—Swimming Home (2011), Hot Milk (2016), and her latest, The Man Who Saw Everything—all have moments of omniscience, short scenes interspersed in the text in a voice distinct from the rest of the narrative. This leads to a sense of uncertainty and wonderment. Who is speaking? At what point in time are we? Her books hover between dream and reality, consciousness and unconsciousness. It would be tempting to think of them as improvisational, strung together by free association, but that would be wrong. Her novels are meticulously structured. They circle in on themselves, full of repetitions, allusions, and elisions whose logic unfailingly reveals itself at the end. With Levy, you are never quite sure of your footing. But she is.

In The Man Who Saw Everything, another pearl necklace appears but, perhaps as a tribute to Colette, on a man: a rakish, ravishing, mascara-wearing young historian named Saul Adler. After Saul’s mother died, his father bequeathed him her necklace. “And then how long would it take to explain that he did not expect his son to wear the pearls?” Levy writes.

When the novel opens, it is 1988. Saul is working on a lecture about “the psychology of male tyrants,” which leads him to find connections between Stalin and his own father. His older brother, similarly, was “always up for a bit of cruelty.” Saul remembers being at a pub with his father once and overhearing him ordering a pint of beer for himself and a “glass of red for the nancy boy.” Barely five pages into the book we are presented with two models of masculinity: Saul’s, searching, second-guessing, effeminate; and that of the “male tyrants” of his life, humorless, rigid, violent—predators of his “freakish beauty.”

Saul is set to depart London for research in East Berlin on “cultural opposition to the rise of fascism in the 1930s,” but his mind is taken up more with his magnetic photographer girlfriend, Jennifer Moreau, who abruptly decides to leave him just as he proposes to her. Jennifer has demanded that he never describe her body or how much he admires it, even as she takes evident pleasure in objectifying his beauty. She is a beguiling, jittery character, if not quite a believable one:

“Your eyes are so blue,” she said, climbing on top of me and sitting astride my hips. “It’s quite unusual to have intense black hair and even more intense blue eyes. You are much prettier than I am. I want your cock inside me all the time. Everyone is frightened in the GDR aren’t they? I still don’t understand how the people of a whole country can be locked up behind a wall and not be allowed to leave.”

Levy makes us see Jennifer: pilot cap pulled all the way over her eyes, traipsing naked in and out of the tiny sauna in the basement apartment she shares with two women, one of whom is “a vegan who was always soaking some sort of seaweed in a bowl of water in the kitchen.” Yet perhaps because the descriptions of her are filtered through Saul’s eyes, Jennifer remains a little cartoonish: a New Wave starlet, a wannabe Lee Miller, a model-turned-photographer. “She looked so excited and young and mean,” Saul thinks.

Advertisement

It is Jennifer’s idea to photograph Saul crossing Abbey Road in a white suit and to send the Beatles-inspired photo to his future host in East Berlin, whose sister, they have learned, is a fan of the band. But as Saul steps off the pavement, he is almost hit by a car. He is mostly unhurt, but the accident looms over the novel and will reappear, in different form, in its second half. Levy employs this kind of repetition and foreshadowing often in her work, toying with the chronology of her tautly devised narratives.

After Saul’s accident, small anachronisms and incongruities begin to populate the text like specters from another time and place: the driver who had nearly hit him holds a cell phone (in 1988?) from which someone hisses invectives while he touches Saul’s hair “as if he were touching a statue or something without a heartbeat”; a florist is “terrified of flowers”; a Wal-Mart plastic bag blows through windswept London. (“That’s odd,” one of the characters thinks. “Isn’t Wal-Mart American?”) Later, there’s this exchange between Saul and his German host’s sister:

“Listen, Luna.” I felt as if I were floating out of my body as I spoke. “In September 1989, the Hungarian government will open the border for East German refugees wanting to flee to the West. Then the tide of people will be unstoppable. By November 1989, the borders will be open and within a year your two Germanys will become one.”

“You are lying to me.” She made her two fingers into a revolver and shot herself in the head.

It’s as if, after the accident, time in the novel becomes elastic, or else creeps to a halt, much as it does when Septimus Warren Smith steps into traffic on Bond Street in Mrs. Dalloway (the theme of gender fluidity is Woolf-inspired, too) or, even closer to Levy’s arsenal of influences, when James Ballard sends his car spinning in J.G. Ballard’s Crash. These novels all depict haunted young men who are hemmed in by society’s fixed notions of what it means to be a man. They are symptomatic of their respective eras: a traumatized war veteran in the case of Woolf, a technology-and-sex obsessive in the case of Ballard, a dreamy and confused (and Jewish) Englishman transplanted to the Communist East in the case of Levy.

Levy has praised Ballard for incorporating both Freud and Surrealism, two “very un-British influences,” into his novels and short stories. The same could be said of her. Less transgressive and more stylistically palatable, Levy’s novels nevertheless rely on Ballard’s use of defamiliarization and estrangement, what he once called the “private mythology” of a writer’s obsessions. She returns to the same themes and images over and over in her work. Pearls. Swimming pools. Howling dogs. Wandering Jews. Daughters attempting to please difficult mothers. (From Hot Milk: “I am always thinking of ways to make water more right than wrong for my mother.”) Absent—or absentminded—fathers. Families that are “neither unhappy nor happy” (a description that recurs, in slight variation, in three of her books). All of these are signposts through Levy’s singular terrain. Her novels, short stories, and two memoirs vary greatly in their preoccupations, but they all plumb what happens when, in her words, “reality slips.”

In The Man Who Saw Everything, reality “slips” quite literally. The oddities that accumulate in the novel’s first half gain clarity in the second. It is now 2016, a day after Britain has voted to leave the European Union. Saul Adler, in his mid-fifties, is lying in a London hospital in a semiconscious state. The accident that brought him there is conflated in his mind with the one on Abbey Road thirty years earlier, and it takes some sleuthing to untangle the two and sort out the present characters from their past iterations. The levity and mystery of the first half of the book give way to narrative-sapping backstory and wooden summaries. “Now, nearly thirty years later, while I was lying on my back in University College Hospital, I seemed to have gone back in time to that trip in the GDR in my youth,” Saul thinks. You can almost see the misplaced editor’s note urging Levy to spell it out.

Advertisement

We learn that part of the reason Jennifer broke up with Saul all those years ago was that she had caught him leering at one of her roommates. This seems wholly out of character, since Saul berates her at one point for being “anti-need,” telling her, “That was your thing, you didn’t need me.” We learn, too, that when Saul saw Jennifer again after his return from Berlin, she was four months pregnant with his child; she later took the baby to America in circumstances that became tragic. All this information appears in clipped chapters, as if Levy is breathlessly trying to bring us up to speed. This results in mannered dialogue:

“You took our son to America,” I was suddenly shouting. “You more or less kidnapped my son.”

The sun was rising over the Euston Road. We could both see strips of orange sky through the blinds.

“It’s like this, Jennifer Moreau”—my voice was surprisingly loud: “I have not forgiven you.”

“I have not forgiven you either, Saul Adler.”

One year after Jennifer left, Saul was reunited with another lover—his German host, Walter Müller—with whom he had fallen deeply in love while he was in East Berlin. He arrives at their meeting place early and can hardly contain his excitement, but when Walter appears, he seems harried. We quickly learn why: he has a wife and two children in tow. This allows for a lovely description of family life:

Helga found a box of crayons and paper in her bag and suggested her daughter sit on her lap. Hannah shook her head and crawled under the table. All conversation had stopped. It was as if the family were an organism, each part depending on the other part to survive the next two minutes.

On the novel goes, between keenly observed scenes and more affected ones. In one powerful vignette, we see Saul as he regards his face in the mirror for the first time since his (second) accident:

Fuck off I hate you, I said to the middle-aged man staring back at me. His hair had been shaved. He was a skull. His eyes a shock of blue in his pale face. He had high cheekbones. A cut on the cheek and on the lip. His eyebrows were silver. Where have you gone, Saul? All that beauty blown to bits.

But even then, Levy can’t help interjecting:

Who were you? What languages do you speak? Are you a son and a brother and a father? Are you an acquisition? How do you get along with your female colleagues? What is the point of them, in your view?… In what ways do you thwart, oppose, derail or support each other?

None of this flourish seems truthful, however one might wish that it were. In particular, the line about thwarting or supporting female colleagues mimes language uncomfortably close to a human resources booklet. Surely no man stares at his reflection and has such a thought.

Compare that authorial heavy-handedness with Levy’s extraordinary novel Swimming Home, which begins with a man and a woman driving at midnight after a sexual encounter the man has come to regret. The scene reappears, in terser form, later in the book. By then we have come to know the characters involved: one is Joe Jacobs, better known to his readers as JHJ, an important and self-important poet whom Levy simultaneously inflates and pleasingly punctures:

When they got back to the villa, Joe walked through the cypress trees to the garden, where he had set up a table and chair to write in the shade. For the last two weeks he had referred to it as his study and it was understood he must not be disturbed, even when he fell asleep on the chair.

The other is Kitty Finch, a self-fashioned botanist and clinical depressive from North London with crooked teeth, a stammer, and a body that “looked like she’d been sculpted from wax in a dark workshop in Venice.”

That last description is courtesy of Joe, who finds himself aroused by Kitty despite himself. “Whoever had made her was clever,” he thinks. “She could swim and cry and blush and say things like ‘hogged it.’” Joe’s teenaged daughter finds Kitty mesmerizing—all-knowing, possessed of mystical powers, reminiscent of a medusa, another of Levy’s favored images. But a family friend vacationing with them at the French villa, who loathes Joe’s pompous flights, regards Kitty coolly: “She was almost pretty, with her narrow waist and long hair glowing in the dark, but ragged too, not far off someone begging outside a train station holding up a homeless and hungry sign.”

Levy began her career as a playwright, and her dramaturgical facilities are on display here. This is what she does best: focusing on the way one character appears in the eyes of another, ping-ponging characters off one another so that our view of them continually shifts, refocuses, and recalibrates to allow for others’ perceptions—the way we do all the time in real life. Levy is less interested in interiority than in the exact moment that interiority intersects with the outside world, often leading to anguish. In Swimming Home, Madeleine Sheridan, an elderly British expatriate living next door to Joe’s villa, receives an unexpected visit from him. She offers him a bowl of Andalusian almond soup, which he accepts. But then:

Something terrible happened. He took a sip and felt something tangle with his teeth, only to discover it was her hair. A small clump of silver hair had somehow found its way into the bowl. He was mortified beyond her comprehension, even though she apologized, unable to fathom how it had got there. His hands were actually shaking and he pushed the bowl away with such force the soup spilt all over his ridiculous pinstriped suit, its jacket lined with dandyish pink silk. She thought a poet might have done better than that. He could have said, “Your soup was like drinking a cloud.”

There’s an amusing distance between Levy’s novels, which tend to take place—perhaps wishfully—under sun-scorched skies, and her two “working autobiographies,” which chronicle the indignities of English winter when fountains are forever “winterized” and “the London pavements smelt of old coins.” Her memoirs pull back the curtain—the screensaver?—on the days she spent writing her two breakthrough novels, Swimming Home and Hot Milk. (Both were nominated for the Man Booker Prize, as was The Man Who Saw Everything; her previous five novels can generously be called “experimental,” which is to say unripe—a novelist coming into her own.) She wishes to lead a “romantic writer’s life,” to write only when inspiration strikes while gazing at the crackling flames of a wood fire. But her writing shed is not heated, and there are bills to pay. “Staring into the flames doesn’t help the word count anyway,” a friend says, trying to encourage her. Levy concurs: “The writing life is mostly about stamina. To get to the finishing line requires the writing to become more interesting than everyday life, and a log fire, like everyday life, is never boring,” she writes in The Cost of Living.

Although Levy’s characters are English, often by way of foreign ancestry, their stories tend to unspool on the beaches of Almeria and Alpes-Maritimes, in Berlin and in Athens, representing a porous, cosmopolitan (usually well-heeled) Europe that is on the threshold of transformation. Greece “can’t pay its bills. The dream is over,” one character laments in Hot Milk, a richly drawn novel told in the first person by a bookish and adrift narrator saddled with caring for her hypochondriac mother. In The Man Who Saw Everything, we are reminded of Karl Marx’s line about a specter haunting Europe. Levy shows us layers of cultural textures that her characters seamlessly glide through and seem to take for granted. Inadvertently, her novels may be as good a specimen as any of the Remain camp.

In one seaside restaurant—in the Caribbean this time—Levy, or rather the narrator of The Cost of Living, who is “close to myself and yet is not myself,” overhears a conversation between a young Englishwoman and a man the young woman nicknames Big Silver, a tanned and tattooed American in his forties, with long silver hair piled in a bun. Big Silver chats up the woman until after a while she interrupts him. “Her conversation was interesting, intense and strange,” Levy writes. The woman begins to tell him a story about scuba diving in Mexico, being entirely submerged underwater, only to resurface and find that the weather had changed and a storm was rolling in. The woman glances at him, to see if he is following, but Big Silver is distracted. “You talk a lot don’t you?” he tells the woman.

Levy’s work examines the question of who gets to speak. She structures Things I Don’t Want to Know (2014) as a riposte to George Orwell, who in 1946 identified four motives for the writer to write, “putting aside,” he added almost parenthetically, “the need to earn a living.” Levy argues that only a certain class of men can afford to set such considerations “aside.” Orwell’s first motive was the writer’s “sheer egoism.” Levy demurs. “Even the most arrogant female writer has to work over time to build an ego that is robust enough to get her through January, never mind all the way to December,” she writes.

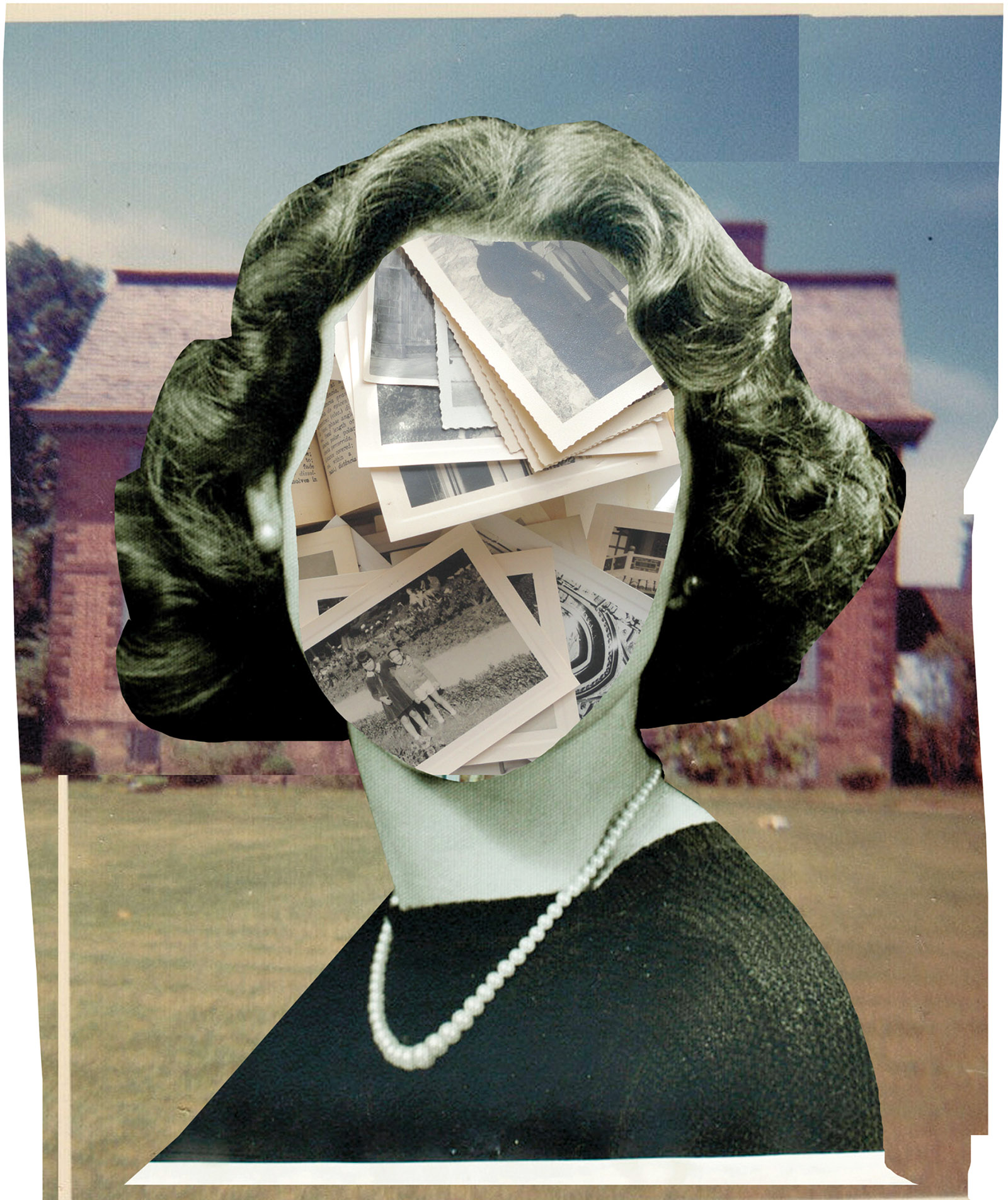

In that book, she rebels against society’s notion of womanhood as a kind of oxymoron, “passive but ambitious, maternal but erotically energetic, self-sacrificing but fulfilled.” The purpose of Levy’s memoirs, she has said, is to lift this “mask of patriarchy.” When she does, she discovers, somewhat startlingly, that even she has been complicit all along: “The wife also wears a mask and her face grows to fit it.” She comes to realize that “femininity, as a cultural personality, was no longer expressive for me. It was obvious that femininity, as written by men and performed by women, was the exhausted phantom that still haunted the early twenty-first century.” Perhaps it is no wonder, then, that The Man Who Saw Everything concerns itself with masculinity and its own myriad masks.

As when listening to that young woman’s conversation on the beach, one finds, on reading Levy, that she has likewise dispensed with the customary and “broken with the usual rituals” of fiction. The experience of reading her is much like the jolt and pleasure of being submerged in water—resurfacing to find that the weather has turned.