In the 1970s, when Shoshana Zuboff was a graduate student in Harvard’s psychology department, she met the behavioral psychologist B.F. Skinner. Skinner, who had perhaps the largest forehead you’ll ever see on an adult, is best remembered for putting pigeons in boxes (so-called Skinner boxes) and inducing them to peck at buttons for rewards. Less well remembered is the fact that he constructed a larger box, with a glass window, for his infant daughter, though this was revealing of his broader ambitions.

Zuboff writes in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism that her conversations with Skinner “left me with an indelible sense of fascination with a way of construing human life that was—and is—fundamentally different from my own.” Skinner believed that humans could be conditioned like any other animal, and that behavioral psychology could and should be used to build a technological utopia where citizens were trained from birth to be altruistic and community-oriented. He published a novel, Walden Two (1948), that depicted what just such a society would look like—a kind of Brave New World played straight.

It would risk grave understatement to say that Zuboff does not share Skinner’s enthusiasm for the mass engineering of behavior. Zuboff, a professor at Harvard Business School since 1981, has made a career of criticizing the lofty ambitions of technoprophets, making her something of a cousin to the mass media critic Neil Postman, author of Technopoly (1992). Her intimate understanding of Skinner gives her an advantage that other technoskeptics lack. For as she posits in her latest book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, we seem to have wandered into a dystopian version of Skinner’s future, thanks mainly to Google, Facebook, and their peers in the attention economy. Silicon Valley has invented, if not yet perfected, the technology that completes Skinner’s vision, and so, she believes, the behavioral engineering of humanity is now within reach.

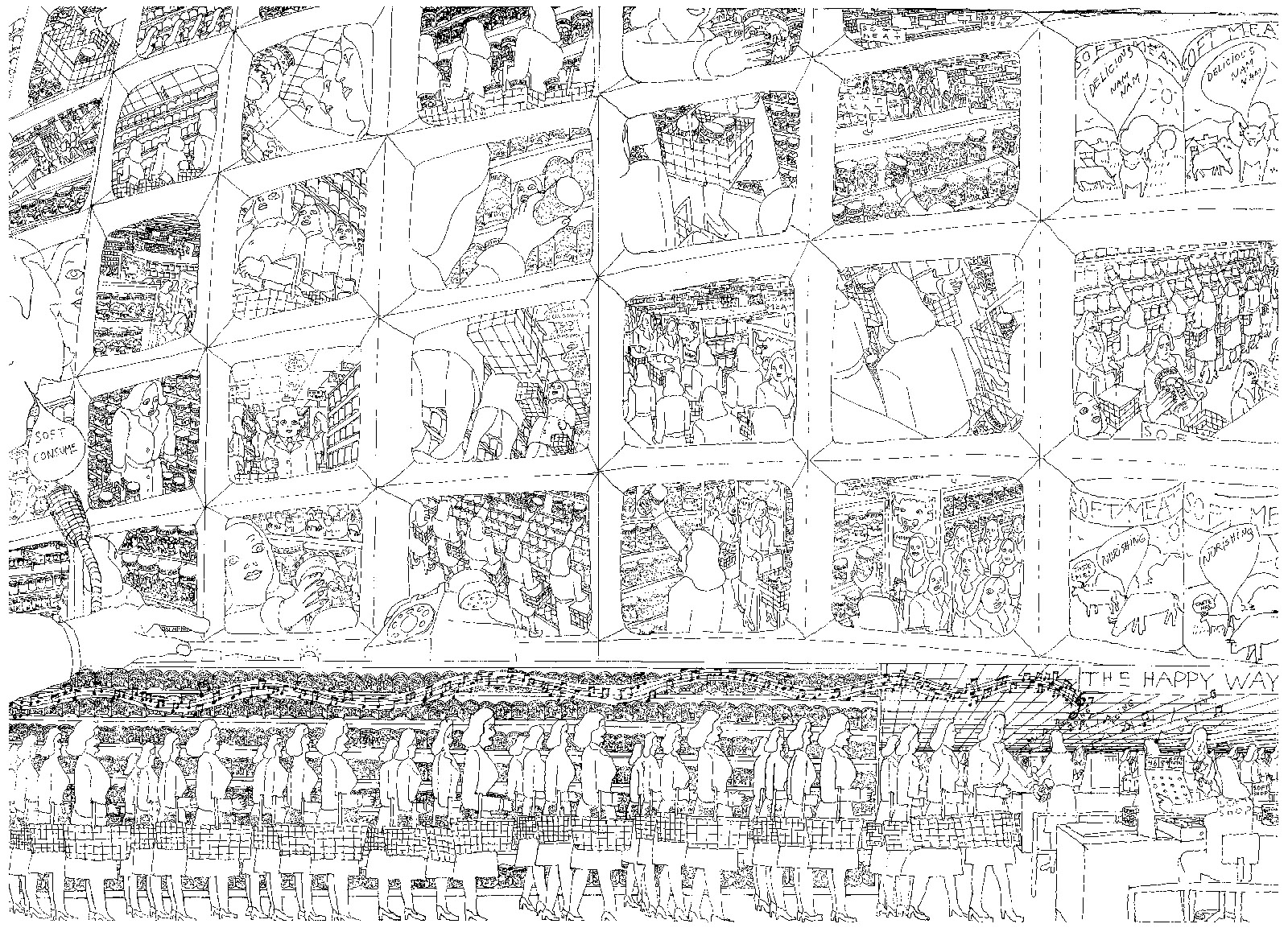

In case you’ve been living in blissful ignorance, it works like this. As you go through life, phone in hand, Google, Facebook, and other apps on your device are constantly collecting as much information as possible about you, so as to build a profile of who you are and what you like. Google, for its part, keeps a record of all your searches; it reads your e-mail (if you use Gmail) and follows where you go with Maps and Android. Facebook has an unparalleled network of trackers installed around the Web that are constantly figuring out what you are looking at online. Nor is this the end of it: any appliance labeled “smart” would more truthfully be labeled “surveillance-enhanced,” like our smart TVs, which detect what we are watching and report back to the mothership. An alien might someday ask how the entire population was bugged. The answer would be that humans gave each other surveillance devices for Christmas, cleverly named Echo and Home.

Most of us are, at bottom, quite predictable. Do you, perhaps, reliably wake up at 7:21 am, take your coffee at 8:30 am, and buy lunch between 12:18 pm and 12:32 pm? If you’ve just had a fight with your spouse, might you be expected, within the next twenty-four hours, to spend money on something self-indulgent? Does reading news about the latest political outrage tend to prompt an hour of furious clicking? And despite flirtations with radical politics in late adolescence, do you always vote for the presidential candidate who is considered a safer choice but has overarchingly progressive values? Basic science suggests that the more that is known about you, the more predictable you become. Once your behavior is known, to the extent that it can be predicted, it—you—can also be manipulated.

How? Skinner demonstrated his theory of behavioral control by so-called operant conditioning in rats. He would place hungry rats in boxes. They came to realize that pressing a lever on one side of the box delivered a snack: after several repetitions, the rat, upon being deposited in the box, learned to head straight for the lever. As for humans, the idea is that if the tech industry knows where you are and what you like, it can use a variety of tricks and techniques—updates, buttons, listicles, and more—to create the levers we are conditioned to pull (or click) on. All of this induces us to make choices in slightly different ways than we might have otherwise, which is known as behavioral influence.

To most people, the assertion that we are living in Skinner boxes might sound alarming, but The Age of Surveillance Capitalism goes darker still. Skinner, at least, saw himself as a do-gooder who would save humanity from its own delusions. His behavioral engineering was meant to build a happier humanity, one finally at peace with our lack of agency. “What is love,” Skinner wrote, “except another name for the use of positive reinforcement?”

Advertisement

Zuboff, in contrast, sees Silicon Valley’s project of behavioral observation in the service of behavior control as lacking an interest in human happiness (other than as a means); its goal is profit. That’s why Zuboff calls it “surveillance capitalism.” If “industrial capitalism depended upon the exploitation and control of nature,” then surveillance capitalism, she writes, “depends instead upon the exploitation and control of human nature.” The term refers to the idea, just described, that we spend our days under constant surveillance, motivated by the offer of small rewards and punishments—radical behavioralism made flesh.

Her book is not without flaws. It is far too long, often overwrought, and employs far too much jargon. Its treatment of Google, which dominates the first half, will strike anyone who has spent time in the industry as too conspiracy-minded, even for those disposed to be critical. Other books, like Bruce Schneier’s Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles to Collect Your Data and Control Your World (2015), offer more technically sophisticated coverage of much of the same territory.

But I view all of this as forgivable, because Zuboff has accomplished something important. She has given new depth, urgency, and perspective to the arguments long made by privacy advocates and others concerned about the rise of big tech and its data-collection practices. By providing the crucial link between technological surveillance and power, she makes previous complaints about “creepiness” or “privacy intrusions” look quaint.

This is achieved, in part, through her creation of a vocabulary that captures the significance of tech surveillance. Her best coinage is almost certainly the title of the book, but there are others of note, like “prediction products”—items that employ user data to “anticipate what you will do now, soon, and later” and then are traded in “behavioral futures markets”; or “the extraction imperative,” which is her phrase for what motivates firms to collect as much behavioral and personal data as possible. The “dispossession cycle” is the means, for Zuboff, by which this is accomplished. Of the essential amorality of the tech industry, she says, dryly, that “friction is the only evil.”

Viewed broadly, Zuboff has made two important contributions here. The first is to tell us something about the relationship between capitalism and totalitarian systems of control. The second is to deliver a better and deeper understanding of what, in the future, it will mean to protect human freedom.

It has long been a cornerstone of Western belief that free markets are a bulwark against the rise of tyrannical systems—in particular, against the kind of surveillance and spying on citizens practiced in the Soviet bloc. Capitalism, the theory went, venerated privacy and protected against surveillance through its embrace of property as value. That seemed most obvious in the form of houses with thick walls and individual bedrooms, but also in semi-private spaces, like bars and motels. If private spaces for every individual were once (say, in the sixteenth century) only something the rich had, the spread of wealth to a propertied middle class and the building of homes with separate rooms (the invention of “upstairs”) is what made it plausible for legal thinkers like Louis Brandeis to speak of the masses enjoying a right to privacy, to be unwatched—a right to be “let alone.” It is not surprising that we don’t begin to see the legal idea of privacy form until the eighteenth century, with the spread of private spaces in which one could conceal oneself from “the unwanted gaze,” whether it belonged to neighbors or government.

Consider the ways that, by the 1960s, the rise of a propertied middle class had put each man in his castle, each drinker in his saloon, each employee in his own office. Consider the ways in which private physical spaces (like bedrooms), along with semiprivate spaces like motels, bathhouses, and dance clubs, created their own expectations of privacy. (It is very possible that various examples of counterculture—the rejections of Victorian morality, the gay rights movement—came about when private space permitted individuals to do forbidden things unwatched.) The same happened with the first private virtual spaces like personal computers and hard drives. Capitalism, which called all of these things types of value, pressed for more private spaces.

But what we’re learning is that the symbiosis between capitalism and privacy was maybe just a phase, a four-hundred-year fad. For capitalism is an adaptive creature, a perfect chameleon; it has no disabling convictions but seeks only profit. If privacy pays, great, but if totalizing control pays more, then so be it.

In a capitalist system, the expected level of privacy can actually be captured by one single equation. Is there more money to be made through surveillance or through the building of walls? For a long time, the answer was walls, because walls made up houses and other forms of private property. Meanwhile, if you asked someone about the size of the “surveillance industry” in, say, 1990, they’d probably have looked at you funny. The conversation would have been about the hiring of private detectives, or the hidden microphones popularized by the Watergate break-in. To speak of surveillance as a source of economic value would have been nothing short of ridiculous.

Advertisement

Today, the balance has shifted. There is still money in building walls, but the surveillance industries must be counted as among the most significant parts of the economy. Surveillance is at the center of the business models of firms like Google and Facebook, and a part of Amazon, Uber, Lyft, and others. Surveillance capitalism is expanding to other industries: Admiral, a British insurance firm, uses Facebook data to help price its products differently to different prospective customers. (It seems that people who write in short, concrete sentences and use lists are safer drivers; excessive use of exclamation points suggests recklessness behind the wheel.) Life insurance firms like John Hancock offer discounts tied to an agreement to monitor the customer’s Fitbit usage. And these are just examples that happen to fit the journalistic imperative of being easy to describe.

Zuboff is right to argue that something transformational happened in the early twenty-first century in the relationship between capitalism, privacy, and, by extension, human autonomy. What emerged, she thinks, is a new form of power, which she terms “instrumentarianism” (not her best coinage). This form of power, according to her, does not depend on coercion or terror, as under a dictatorial system, but “ownership of the means of behavioral modification.” In other words, she thinks that the future belongs to whoever is running the Skinner boxes.

But her description of the emergence of this new form of power is not, as I’ve already suggested, the book’s strong point. Zuboff tells a story of an evil and mysterious Google that makes the awesome discovery of the power of “behavioral surplus” and hides it from the world while piling up riches, like some kind of Victor Von Doom hiding somewhere south of Palo Alto. Her narrative will please confirmed Google haters, and her distance from the industry does save her from being anything like an apologist for the power of the companies, but it risks caricature.

In Zuboff’s account, the purported idealism of Google’s founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, always hid darker motives. Their dedication to open platforms, like their “don’t be evil” motto, was just a kind of smoke screen. But in seeing such sinister intent, Zuboff overcredits Google relative to lesser-known figures like Lou Montulli, an engineer who, while at Netscape, invented the browser “cookie”—the Web’s first and most important surveillance tool.

In my view, the history of Google is a bit less Doctor Doomian and more Faustian. It’s a tale of a somewhat idealistic and outlandishly ambitious company whose mission became corrupted by good old-fashioned revenue-demanding capitalism. I see its IPO as the turning point: while claiming it wanted to be different, the firm adopted a corporate structure that ultimately had only superficial distinctions from any other Delaware-incorporated company. Its role in the rise of surveillance capitalism is therefore a story of a different set of human failings: a certain blindness to consequence, coupled with a dangerous desire to have it all.

Though we may quibble over the narrative, Zuboff isn’t wrong about the result. Google’s success with a surveillance-driven advertising model did inspire others, most especially Facebook and Amazon but also the cable industry and “share economy” firms like Uber, to engage in a race to see who can collect the most information about its users, leading us into what is indeed the age of surveillance capitalism.

All of this leaves one hard question: Just how much does any of this matter? Do Google and Facebook, viewed as agents of behavioral modification, really have a greater influence on us than either traditional advertisers or other sources of influence? The Marlboro Man, who debuted in 1954, was credited with a 3,000 percent increase in sales of a cigarette that had once been marketed as a woman’s brand (original slogan: “Mild as May”). And how might we measure the influence of Google against that of an outlet like Fox News, which follows a more traditional propaganda formula? Can platform influence really be compared to the power of earlier forms of propaganda, like the broadcasts that united Germany behind Hitler?

Zuboff, anticipating these objections, warns us not to be blind to new forms of power. (As the twentieth-century French philosopher and Christian anarchist Jacques Ellul pointed out, it is those who think themselves immune to propaganda who are the easiest to manipulate.) But what makes it hard to answer the question is the fact that it is entwined with a different phenomenon: the return, to center stage, of the dark arts of disinformation. No one can deny the present influence of social media (see Donald Trump, election of). Yet much of that power seems to derive from traditional propaganda techniques: false or slanted information, scapegoatism, and, above all, total saturation with repetitive messages.

The tools of surveillance capitalism clearly aid and abet propaganda techniques, but they are not the same thing. To be sure, the microtargeting made possible by data collection has made it easier for the Russian government to reach the right American voters with fake news and divisive information. But I’m not certain that this is what Zuboff has in mind when she depicts “instrumentarianism” as a new form of power.

Where she is right is in asserting that state power and platform surveillance will combine in terrifying ways. In fact, where Zuboff operates at exactly the right pitch of darkness is her discussion of surveillance capitalism’s marriage with the state. Here it is not Google or Russia, but the Chinese government that is pointing the way.

For some years, the Chinese state has been trying hard to establish a social credit system (社会信用体系) to keep a running tally of each citizen’s reputation. With the stated goal of increasing public trust, the idea, while only partially implemented at this point, is to create a general sociability score that can be increased by “good” behavior, such as donating blood or volunteering, and decreased by antisocial behavior, such as failing to sort litter or defaulting on debt. Losing social credit has already led in unpleasant directions for some: it was reported in 2019 that, owing to “untrustworthy” conduct, 26.82 million Chinese citizens were barred from buying airplane tickets and 5.96 million from traveling on China’s high-speed rail network. And China goes even further in its coupling of military-style surveillance technologies with big-data analytics to track and control the Muslim Uighurs in Xinjiang, using checkpoints, cameras, and constantly updated files on virtually every citizen of Uighur descent.

It is hard to imagine anything more Skinneresque than the engineering of social trust through rewards and punishments. There might be a few—true believers, indeed—who can see in China’s social credit system a good model for our future. But for the rest of us, the urgent question is: How can we stop it, or something like it, from happening here? What, if anything, can be done to avoid the dystopia we will face when the last remaining gaps are filled in, when our behavior is better modeled and even easier to control?

Reading Zuboff leads to an important answer to this question. The protection of human freedom can no longer be thought of merely as a matter of traditional civil rights, the rights to speech, assembly, and voting that we’ve usually taken as the bedrocks of a free society. What we most urgently need is something else: protection against widespread behavioral control and advanced propaganda techniques. And that begins with completely rethinking how we control the collection of data.

That will require not a privacy statute, as some might imagine, but a codified antisurveillance regime. We need, in other words, laws that prevent the mass collection of behavioral data. Most people think that privacy laws are in place to do this, but existing privacy laws, including the European privacy law, have done little to actually slow down the collection of data. Instead, they supposedly give us more control over when data is collected and how it is used, which in practice just means pop-up notices and the placing of some limits on how data is used. None of this is bad, but it doesn’t actually prevent surveillance. There is a reason that Facebook says it welcomes European-style privacy regulation.

A real antisurveillance law would accomplish something different: it would stop the gratuitous surveillance and the reckless accumulation of personalized data. It would do that by allowing only the collection of data necessary to the task at hand: an app designed to help you mix cocktails would not, for example, be allowed to collect location data. Gratuitous surveillance would be banned—and after collecting data, firms would be forced, by default, to get rid of it, or fully anonymize the rest of it.

What we have learned, what Skinner and secret police alike have realized, is this: to know everything about someone is to create the power to control that person. We may not be there yet, but there is a theoretical point—call it the Skinnerlarity—where enough data will be gathered about humanity to predict, with some reasonable reliability, what everyone on earth will do at any moment. That accomplishment would change the very structure of experience. As the legal scholar Jonathan Zittrain has said, it would make life “a highly realistic but completely tailored video game where nothing happens by chance.”

That’s why we must dare to say what would sound like blasphemy in another age. It may be that a little less knowledge is what will keep us free.

This Issue

April 9, 2020

Stuck

In the Time of Monsters