The shocking dimensions of China’s repression in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region are now beyond dispute. In early 2017, after spending years perfecting a high-tech surveillance regime in its only Muslim-majority region, the Chinese state began a program of mass internment that has seen the disappearance without trial of at least a million Uighurs, Kazakhs, and other Muslim citizens into a vast network of internment camps and prisons. Many camp inmates have been compelled to work in factories, and the fruits of their forced labor have increasingly shown up in the supply chains of multinational corporations like Kraft Heinz and Adidas. More recently, an extensive campaign of forced sterilization aimed at Uighur women has come to light, grimly echoing past policies implemented against indigenous peoples and minorities elsewhere in the world, including the United States.

In addition to repressing Uighurs through imprisonment and sterilization, the Xinjiang authorities have mounted a sustained assault on Uighur culture and identity. This has included the destruction of graveyards and religious sites, the elimination of Uighur-language education, and the widespread banning of Uighur books. The mass detentions have targeted cultural figures—writers, poets, intellectuals, musicians—with special ferocity, sometimes accompanied by public denunciation campaigns. As renowned writers have vanished into the camps and prisons, their books have been pulled from store shelves. Publishing in Uighur, lively and diverse through late 2016, has been reduced in the last three years to a pitiful trickle of state-approved journals.

During several years working in Xinjiang as a Uighur-English translator, my favorite work usually involved poetry. I spent many hours in conversation with Uighur writers like Perhat Tursun, known for his edgy verse and his controversial novel The Art of Suicide; Idris Nurillah, a poet and translator who also ran a wine shop; and Shahip Abdusalam Nurbeg, a schoolteacher well known for his endlessly experimental poetry. Their company was as exciting as their work, in part because poetry is such a vibrant genre in Uighur society, as central to national identity as it is to self-expression. It is precisely because of poetry’s power in Uighur culture that these three poets, along with nearly every other prominent Uighur intellectual, disappeared more than two years ago into China’s internment camps.

Yet, as China silences Uighur poets’ voices in Xinjiang, Uighur poets and artists in the diaspora have spoken up, bearing eloquent witness to the catastrophe in their homeland. Some under their own names and others using pseudonyms, these writers and artists, many of whom live in Turkey’s large Uighur refugee community, are giving expression to the pain, as well as the resilience, of their people. Theirs is some of the most powerful and poignant writing I have come across in my dozen years translating Uighur poetry (the translations of the poems that follow are mine).

One of the most accomplished of these poets is Abdukhebir Qadir Erkan. Born in 1990, Erkan grew up in Khotan, an oasis city in the south of the Uighur region. Influenced both by canonical poets and by avant-garde verse, he began writing poetry in high school, but trailed off after leaving school early to work in his family’s drugstore. Over the next decade, he wrote only a few poems a year, but maintained a strong interest in poetry. In 2016, hoping to study Arabic literature, he left China to begin language studies in Egypt. Aboard the flight, departing a worsening political situation in his homeland for a fresh start abroad, he felt renewed inspiration and began writing poetry on napkins brought by the flight attendant. By the time his plane landed in Cairo, Erkan had written half a dozen poems. In the year that followed, when he wasn’t studying Arabic, he devoted himself to Uighur poetry.

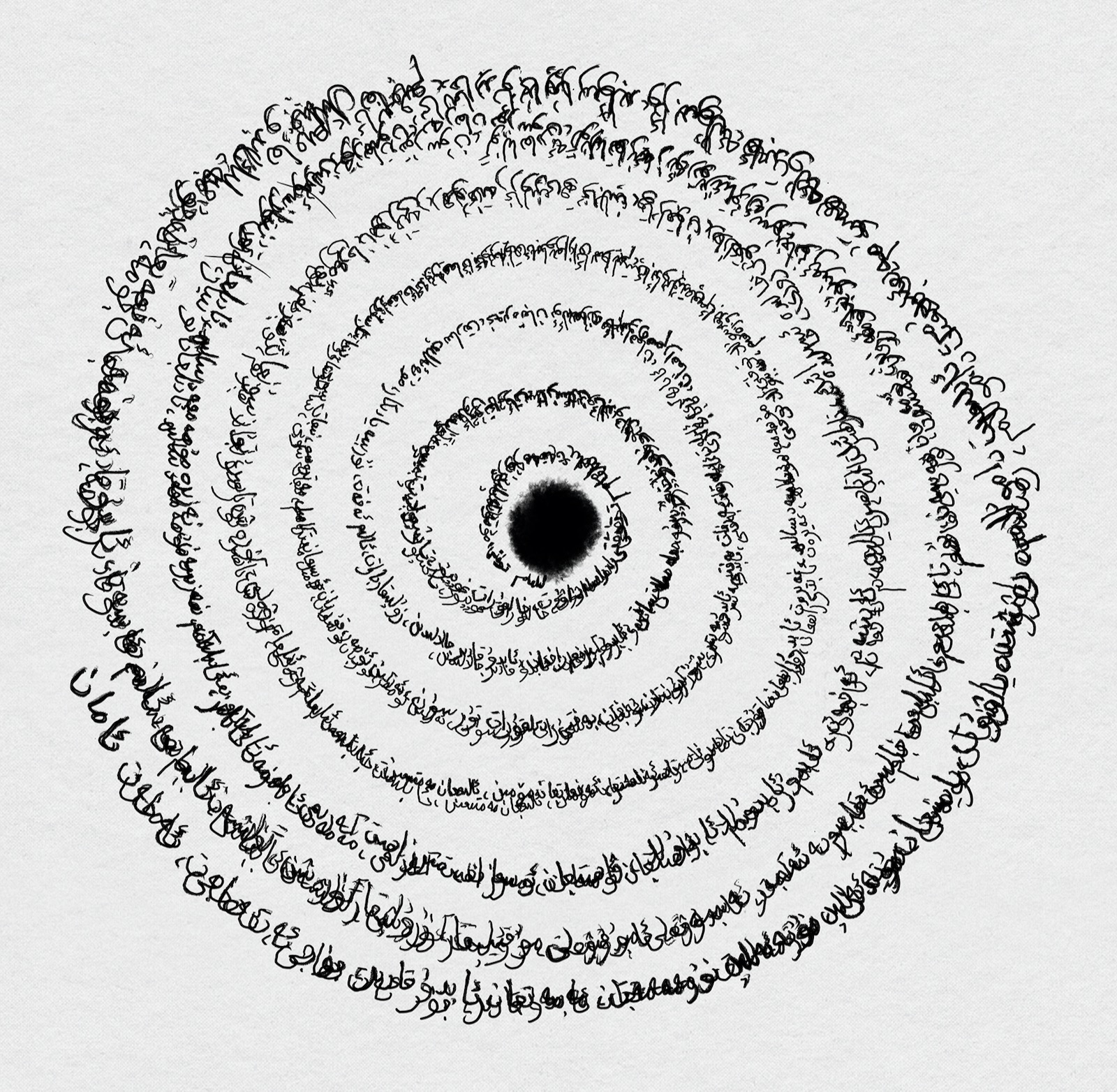

Erkan’s mentor in his poetic work was Shahip Abdusalam Nurbeg, the prominent poet then still working as a schoolteacher in Xinjiang. Nurbeg read all of Erkan’s work, giving him encouragement and guidance that no established poet had shown him before. I know Nurbeg from my years in Xinjiang’s capital, Ürümqi. He would come through town sometimes for dinner with other writers, intellectuals, and translators, and always had a great deal to say, his speech marked by the distinctive accent of his hometown, Kelpin, in central Xinjiang. A gentle, silver-haired man around fifty, Nurbeg is an uncompromising modernist when it comes to poetry. He is perhaps best known for his ambitious Thousand Elegies, a composition consisting of a thousand quatrains built around a strange and compelling symbolism. (“Your face arising in words is the text’s jet-black excitement,” promises the typically elliptical first quatrain.) Nurbeg also edited the most extensive anthology of Uighur poetry ever published in Chinese translation, Burning Wheat, which appeared in 2016 to considerable acclaim.

Advertisement

Even at a distance of thousands of miles, Nurbeg was an irreplaceable mentor for Erkan as the younger poet honed his craft. The two embarked on various projects together, including an effort to reinvigorate classical Uighur poetic genres by rewriting their rules. By April 2017, Erkan had also become fluent enough in Arabic to enter a public speaking competition for foreign speakers of the language. He performed brilliantly, reading his poetry in his own Arabic translations and earning the spirited praise of the Egyptian literary notables who were serving as judges. It was a triumphant moment, coming only fourteen months after Erkan had arrived in the country.

Two weeks later, Erkan had to flee Egypt. The Chinese authorities were pressuring Uighur students in Egypt to return to China, and rumors had spread in Cairo’s Uighur community of detention camps awaiting them on their return. Given the close ties between China and Egypt, the el-Sisi administration seemed unlikely to offer protection to Chinese citizens pursued by their own government, and Erkan left hurriedly for Dubai. After several months, he relocated to Turkey, where he resumed his poetic work and began studying Turkish literature. Three months after Erkan left Egypt, the Egyptian authorities, working in tandem with Chinese officials in Cairo, began rounding up Uighur students. Egyptian families hid some Uighurs, but hundreds were deported to China. Few have been heard from since.

Several weeks after the deportations in Egypt began, Erkan received more bad news. As the mass detentions in Xinjiang continued, Shahip Abdusalam Nurbeg had been sent to the internment camps, along with hundreds of thousands of other Uighurs. Amid the larger catastrophe unfolding in his homeland, the imprisonment of his mentor was especially devastating for Erkan. In the days following Nurbeg’s disappearance, Erkan penned “Death of the Dusk Seeker,” a fierce, poignant tribute to a teacher torn from his classroom and a poet robbed of his voice:

Building his dwelling in the winds,

gifting the grubs the sun of his skies,

he left for the roads that run dark among letters.

Thirsting for seas that flow from night drops,

living his days outside of the seasons,

sketching his cry in a blossoming chest,

he left his flower with his dark lover.

The buds of his comforting shadows

dug ever deeper in his chest

as he stuttered like a speechless man

through canyons with word-choked memories.*

Now grant him permission

to die as gloriously as a grub.

Let the tongue that darkened as his hair grew white

be a grave in his soul’s ruined temple.

Make a coffin from the blackboard that ate his lungs,

as we mourn him let it be our wake.—August 3, 2017

Of the countless Uighurs and others who have vanished into China’s internment camps, only a small fraction have friends and relatives abroad to tell their stories. For that reason, some writers of the Uighur diaspora have taken it upon themselves to speak for the innumerable unknown victims. Some of the most notable of these works are by Muyesser Abdul’ehed Hendan, a writer and educator in her mid-thirties. A native of Ghulja in the north of the Uighur homeland, Hendan completed a medical degree at Beijing University, China’s top institution of higher education, followed by a master’s in public health in Malaysia. Even during her medical training, she began making a name for herself as a poet and essayist, and by the time she completed her master’s degree, she had resolved to focus on writing. After relocating to Turkey in 2013, Hendan founded Ayhan Education, an organization devoted to fostering and teaching the Uighur language in the diaspora. Like Erkan, she currently lives in Istanbul.

Hendan’s recent prose and poetry grapple extensively with the crisis in her homeland. Most notably, her recently published debut novel, Kheyr-khosh, quyash (Farewell to the Sun), is the first extended work of fiction to focus on the internment camps in the Uighur region. In her poetry, Hendan has likewise given voice to the suffering of camp inmates and their loved ones. In one remarkable poem she published this summer, “He Was Taken Away,” Hendan imagines the pain of an unnamed Uighur woman whose husband has been sent to the camps:

At your morning

at my high noon

at their seaside dusk

at the darkest rostrum of his night

he was taken away.It seemed the sun was glaring at you,

a nightmare seemed to come upon me,

they seemed struck by thunder’s omen.

Sleep seemed pulled out of his life

and he was taken away.Now eyes will pierce through doorsteps,

now no hearts will water the streets,

now water cannot wash the shirt he took off

like a mother washes her lost child’s clothes.

Now time will not run forward,

it will walk heavy like a turtle

with love pushing from behind.

Now all means have faded in the distance

as an anxious woman searches

for barefoot children.

Now the world learns sorrows with no cure,

now fingers count themselves,

often the fingers cut knives.He was like me,

he could see.

He was like you,

he could read.

He was like them,

he could speak.

He was a man,

a man taken away,

with a crime that prisons wrote for him

like a doctor’s prescription.

On a paper written for his death

I will yellow,

you will blanche,

they will turn blue,

and we can never enter his color,

we will find no color like his color.—June 11, 2020

Even for Uighurs who are physically safe in the diaspora, the emotional toll of the last three years has been unrelenting. Many are completely cut off from their families and friends back home, where receiving so much as a text message from abroad can easily bring the Chinese security services knocking at a Uighur family’s door. As a result, many Uighurs abroad have little or no idea how even their immediate family and closest friends are faring amid the mass internments. Nearly every Uighur in the diaspora has experienced the pain of finding that loved ones in their homeland have blocked their text messages, fearing state repercussions.

Advertisement

In numerous documented cases, security officials in Xinjiang have contacted Uighurs abroad and threatened to send their parents, children, or siblings to the camps if those abroad don’t meet various demands: to return to China (and near-certain internment); to refrain from speaking publicly on the Xinjiang atrocities; or to surveil and report on other Uighurs in the diaspora. All of this has created a tremendous amount of suspicion in Uighur diaspora communities, damaging efforts to build solidarity.

Last fall, Yi Xiaocuo, creator of a remarkable website showcasing art on the Xinjiang crisis, sent me a link to a Uighur music video dealing with these issues. Set to the song “Wish,” by the Uighur rock group the Headphones (Tingshighuch), the video conveys in five tightly-filmed minutes the pain, isolation, and doubt experienced by thousands of Uighurs in the diaspora, while offering a simple but powerful message of persistence and unity. I contacted the filmmaker, a Uighur man in his late twenties who uses the pseudonym Asman, to ask if I could prepare English subtitles for the film. He kindly agreed.

Emdilikte (Anymore), written and directed by Aziz Asman, 2018

As the Chinese state works to wipe out Uighur culture and identity, the writers, artists, and activists of the Uighur diaspora are demonstrating that their community will not simply be erased. In Turkey, Europe, and the United States, existing Uighur populations have grown rapidly with an influx of refugees, and cultural organizing has likewise expanded. Institutions like Hendan’s Ayhan Education offer Uighur-language instruction for children growing up outside the Uighur homeland. A number of efforts are underway to digitize as much as possible of the Uighur written heritage, and Uighur-language publishing is burgeoning in Turkey. These are not simply efforts at cultural preservation; they represent a community determined that its culture will not only survive but flourish.

In April 2018, a group of twenty-five Uighur writers gathered in Istanbul to establish the World Uyghur Writers’ Union, to be led by the exile poet Tahir Hamut Izgil. Having left China for the United States in 2017, Izgil was spared the fate of other prominent poets in Xinjiang; but like many Uighur intellectuals in the diaspora, he remains focused on the situation back home and on what he can do to transmit a threatened culture. Izgil currently works as a film producer at Radio Free Asia, whose Uighur bureau has done more than perhaps any other news agency to document the devastation in Xinjiang. He has also continued his poetic work, emerging as a leading voice of the Uighur diaspora. In the first poem he wrote after leaving his homeland, “What Is It,” Izgil gave eloquent expression to experiences shared not only by Uighur refugees, but by all people who have felt the pain of exile, the ambiguity of survival, and the bittersweet duty of memory:

What is it

from far away, from behind the domed water,

that stayed with me, that came along with me?

A weak vow written in the yellowing fog,

audacity standing at an angle

or

the layered dimness passed from hand to hand?These days

are crowded with shattered horizons,

shattered!In the runaway season

if surrender hides deep in the suitcase

if noble doubts run over the weight limit

if dead ends continue onward

if the exodus stalls at the second floor

what is it

that keeps you from seeing I am still alive?So simple are my inner soul and outer face,

oh dark-eyed one,

a tree that reddens from within

turns to stone beside meA spray of sweet-smelling camel grass

grows quickly, blooms open

at the doorstep of the past—November 7, 2017