In 2004 the CBC—Canada’s publicly funded broadcaster—produced a TV competition called The Greatest Canadian, which sought to crown a national figure, living or dead, with the title. (The BBC had produced a similar program in the UK two years earlier.) Despite having the look and feel of a telethon, the show was a hit. More than 140,000 nominations were narrowed down to a list of ten—nine of them white, all of them men—that included Wayne Gretzky, Alexander Graham Bell, former prime minister Pierre Trudeau, and Terry Fox. The most obvious choice would’ve been the indisputably saint-like Fox, who died in 1981 at the age of twenty-two, after running halfway across the country to raise money for cancer research, having lost a leg to the disease.

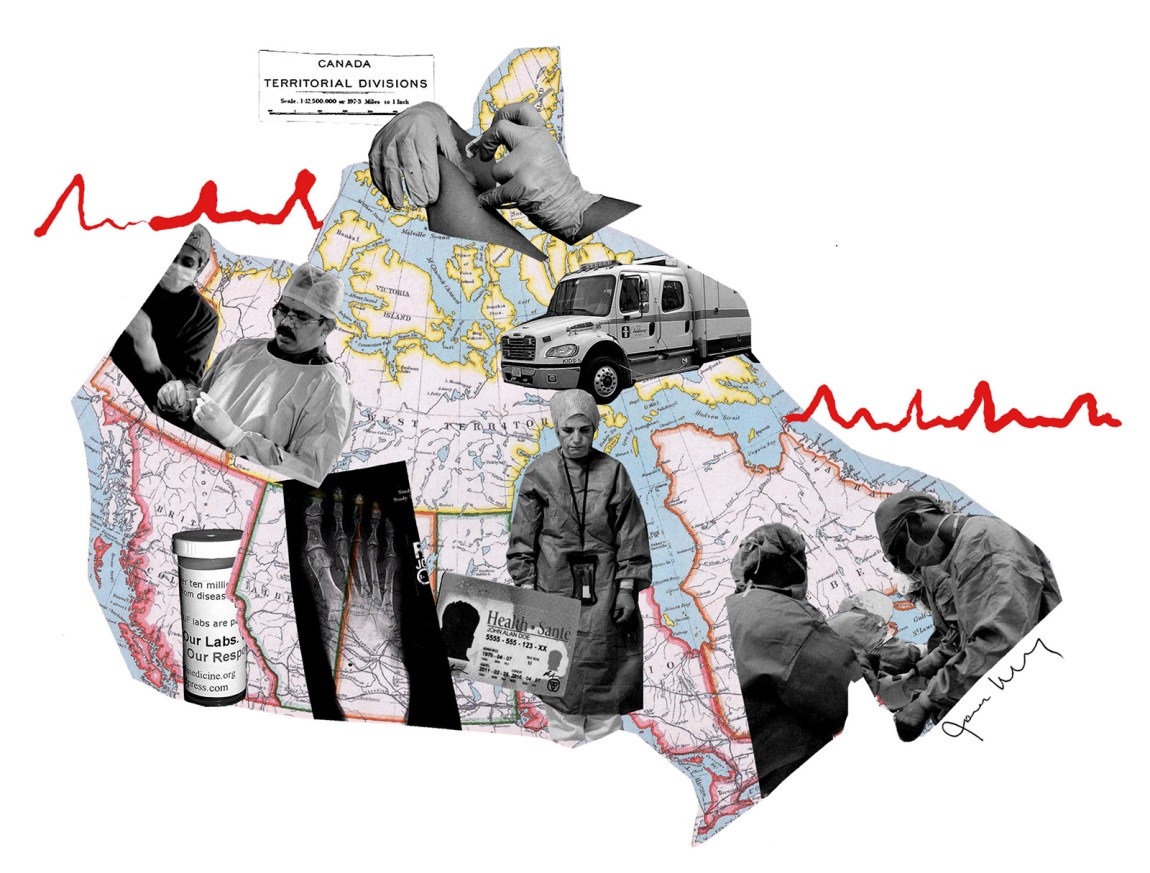

The ultimate winner was not a revered athlete, inventor, artist, or even someone whose name most non-Canadians would recognize. Instead, the show’s viewers picked Tommy Douglas, the socialist politician considered the father of Canada’s single-payer health care system. As premier of Saskatchewan in the 1940s and 1950s, Douglas—over the fierce objections and active opposition of most regional doctors—built a system of publicly funded universal health coverage in that province. Over the following two decades Canada’s federal government, inspired in part by Saskatchewan’s system, made a series of legislative moves to fund similar programs across the country. Finally, in 1984, Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government passed the Canada Health Act (CHA), which enshrines the formal financial structure of the country’s health care system, as well as the broad principles upon which it is based.

Tommy Douglas’s name retains such luster, almost five decades after his death, that it gets invoked even by virtue-signaling right-wing politicians otherwise hostile to Douglas’s socialist ideals—which has prompted the actor Kiefer Sutherland, Douglas’s grandson, to excoriate those who he feels do so in bad faith. Sutherland (like his late mother, the actor Shirley Douglas) has been passionate and vocal in his defense of Canada’s health care system, and has done extensive work on behalf of a public advocacy group called the Canadian Health Coalition.

The reverence in Canada for Douglas is a clear indication of medicare’s centrality to the country’s cultural and political imagination. (“Medicare” is the informal name given to Canada’s national system, which has no official title.) In the introduction to the nearly 360-page report published in 2002 by the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, commissioner Roy Romanow wrote that “Canadians embrace medicare as a public good, a national symbol and a defining aspect of their citizenship.” A national poll taken a decade later found that 94 percent of Canadians consider the country’s health care system “an important source of collective pride.”

Possibly the most astonishing thing about the CHA is that the entire piece of legislation, including both English and French texts, barely fills eighteen pages. By comparison, the 2010 Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, runs to more than nine hundred pages. According to Dr. Jane Philpott, who served as minister of health under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (Pierre’s son) from 2015 to 2017, that brevity is part of the CHA’s “genius”: establishing the bedrock principles of medicare within Canada’s broad and frequently combative federal system requires a document that is simple and direct. Various national accords, reforms, and legal challenges have occurred since the implementation of the CHA, but its overall structure—which guarantees that every Canadian, no matter their health status, their province or territory of residence, or their income level, can visit a doctor or a hospital without having to pay a thing for most treatments and procedures—has remained relatively unchanged since 1984, for better and for worse.

The linkage of national pride to policy can lead to some smugness—especially when Canadians judge their system against that of the US. A nearly decade-old meme called Breaking Bad (Canada) envisions an alternate version of the crime-thriller series in which Walter White has no need to cook meth in order to pay his medical bills, because they are covered by medicare. “You have cancer,” a doctor tells White. “Treatment starts next week.” End of story.

Would Walter White and those around him really have been spared much death and destruction had he lived in Newfoundland instead of New Mexico? The short answer is: Yes, probably. All the procedures that comprise cancer treatment are covered by the country’s single-payer health system. Even long medical wait times—for which Canada gets justly criticized both inside and outside of the country—would not have been a problem in White’s case, as cancer treatments (and critical procedures like cardiac surgery) are not usually subject to such delays. (Though expecting chemo to start “next week” is a bit of a stretch; one month is a more likely time span between diagnosis and the start of treatment.)

Advertisement

From the perspective of a patient, Canadian medicare seems blessedly simple: all health care that is deemed necessary and that takes place in a hospital or a doctor’s office is provided free of charge, with no copays or user fees. When my oldest child was born, in Toronto’s Women’s College Hospital, we were charged only a small rental fee for the optional telephone we requested in the room. (It was 1998.) The same thing—minus the phone rental—happened when my two subsequent children were born: we showed up, hit the maternity ward, and walked out a day or two later with a new baby, provided free of charge. Medicare has covered every one of my kids’ subsequent visits to a doctor’s office for check-ups, as it has the few occasions they’ve spent time in a hospital because of something more serious.

My own Breaking Bad (Canada) moment came in 2016, when a grape-sized lump on the left side of my neck was identified as a cancerous tumor. A little over a month later, I began radiation and chemo at Toronto’s Sunnybrook Hospital. There were other complications and procedures: a preexisting blood condition meant that I had to undergo a series of hours-long plasma transfusions to boost my platelet count. Because the radiation was focused on my neck, I became unable to swallow anything (my sense of taste had vanished long before that), and so underwent surgery to have a rubber external feeding tube implanted in my stomach. On the day my treatment ended, I suffered an extremely painful pulmonary embolism that sent me to the hospital in an ambulance and forced me to self-administer daily blood-thinning shots to the belly for the next five months.

Throughout all of this, the only thing I did in order to receive treatment was show my health card upon each visit. Had I moved to a different province during this time, only the color of the card would have changed. What looks like one system from the outside is actually ten provincial and three territorial systems, each funded with federal dollars and forced to abide by the rules laid out in the CHA, one of which is that care must be portable across internal borders.

It’s hard to argue with free and relatively efficient, which is probably why support for medicare is so consistently high among Canadians. The link between medicare and higher taxes causes a lot of grumbling on radio call-in shows and in the comments section under any story about government health spending, but a 2016 poll revealed solid majority support (nearly 60 percent) for raising income taxes in order to expand the categories of care that get covered. Wait times in emergency rooms and for certain procedures have been a serious issue throughout the country, but there has also been some effort to address them with infusions of cash and attempts to set better benchmarks. Medical bankruptcies do happen, especially among older Canadians—a 2006 study commissioned by the federal government suggested that 15 percent of Canadians over fifty-five cite medical reasons as a primary factor in bankruptcies, although it’s unclear if that means direct medical costs such as prescriptions, equipment, and specialized therapies not covered by medicare, or lost income due to illness. Recent government statistics on bankruptcies show that the percentage has grown since then.

Overall, however, the existing Canadian system is designed to keep people like me from ending up on the street or being forced to start a GoFundMe campaign because of a medical condition or emergency. Roy Romanow’s 2002 report asks whether “the health care system adequately meet[s] Canadians’ needs. The answer is a qualified yes.”

That qualifier is important: the surface simplicity of Canada’s system masks some chronic problems. The biggest is budget pressure: health care spending is the largest item by far in every provincial and territorial budget, making up an average of just under 40 percent of total expenditures and generally growing at a faster rate than the economy. The second-biggest problem is pressure from an aging population that consumes more of the health care budget each year—according to the World Health Organization, the average Canadian life expectancy is a little over 82 years, higher than in the UK (81.4) or the US (78.5), and rising. The problems are not unique to Canada. As Ezekiel J. Emanuel writes in his recent book Which Country Has the World’s Best Health Care?, “All governments of high-income countries are wrestling with how to satisfy—and perhaps adjust—public expectations and demands while reining in future health care cost growth.”*

Advertisement

A third problem, more specific to Canada, is that of government health care administrators who—because of ideology or because it’s just easier—allow illegal private health clinics to flourish, undermining the legitimacy of the system. A fourth problem, and possibly the most acute, is the active threat from both individuals and groups challenging the legitimacy of the CHA’s provisions in court.

Books that warn of the potential demise of medicare are a cottage industry in Canada—the title of Jeffrey Simpson’s Chronic Condition: Why Canada’s Health Care System Needs to Be Dragged into the 21st Century (2012) is typical of the genre. Given the overwhelmingly high poll numbers in support of medicare, calls to tear it down exist only on the fringe of public opinion, but we Canadians love to frighten ourselves with thoughts of how it could disappear. Three recent books are less alarmist in their examinations of the past and current state of Canadian health care, but all three also suggest that good may not be good enough.

Canadians tend to see medicare not merely as reflecting some unique virtue in the national soul, but as a product of it. In Radical Medicine, Esyllt Jones, a history professor at the University of Manitoba, writes that “the popular story of medicare has given its existence an air of historical inevitability” and made it seem like the “natural outgrowth of Canadians’ political and social identity.” Jones seeks to dismantle what she calls “the whiggish narrative of liberal progress” that has developed around medicare, showing how significant the influence of numerous non-Canadian people and ideas was to its early history. The more complicated story that Radical Medicine explores is that of Canadian medicare being inspired by ideas from the Soviet Union, Britain, and the United States, but also veering away from those ideas at critical moments, not always for the better.

Many Canadians (and more than a few Americans) would be shocked to learn that Canada’s cherished health care system contains American DNA. But as Jones writes, “New Deal era movements for health policy reform, while ultimately stillborn, provided key ideas and—crucially to the story of medicare—people to the medical left across the border in Canada.” One of those people was Fred Mott, an Ohio-born physician who served in leadership positions for various New Deal health initiatives before being recruited by Tommy Douglas to head Saskatchewan’s newly created Health Services Planning Commission (HSPC). Mott brought American colleagues with him to Canada, as well as some of the collectivist ideas that were being discussed and worked on in Washington, D.C.—at least until anti-Soviet hysteria killed off any proposal with the taint of socialism on it.

The Soviet Union had a real influence on pre–and post–World War II health care planning in Britain and North America. During the 1930s it was common for Western intellectuals and left-leaning political figures to make pilgrimages to the Soviet Union. Radical Medicine—while letting no one off the hook for willful ignorance about the realities of the Soviet system—shows that some of these figures gleaned useful ideas for health reform back home, the most important being the fundamental principles of “universally available free care, a focus on prevention, and centralized control and planning.”

One Canadian who visited the Soviet Union was Norman Bethune, a surgeon and Communist Party member who died while treating Chinese soldiers during the Second Sino-Japanese War and was eulogized by Mao Zedong. Another was Frederick Banting, the Nobel Prize–winning codiscoverer of insulin (number four on The Greatest Canadian list) who has been invoked by Senator Bernie Sanders as part of his campaign for lower drug prices in the US. Both Bethune and Banting came back from their Soviet sojourns with the strong conviction that socialized health care was moral, necessary, and achievable. Jones quotes from a speech Bethune made in 1936: “The practice of each individual purchasing his own medical care does not work. It is unjust, inefficient, wasteful and completely out-moded.”

Radical Medicine reveals how Bethune, Banting, Mott, and others helped spur the creation of socialized health care in Canada, but also criticizes the ways in which radical ideas for health reform got watered down in the original Saskatchewan experiment by both political realities and political cowardice. Jones spends little time examining the current system, but the evidence in her book suggests that those founding compromises are at least partly responsible for the ongoing problems that lurk within medicare.

Ironically, Bethune’s description of the free-market health system as “unjust, inefficient, wasteful and completely out-moded” is exactly how most critics would describe the current state of Canadian health care. Even ardent supporters of the system acknowledge the accuracy of at least a few of those descriptors.

One major structural problem lies in the distinction Canada’s system makes between funding and delivery. Medicare is paid for primarily with public money, but delivered by private physicians and institutions—albeit highly regulated ones. In contrast to those who work in Britain’s National Health Service, for example, Canadian doctors are not government employees but rather independent contractors who bill the government, which sets the terms for how much money they can make—an inevitable source of tension. (The original Saskatchewan health care legislation was met with a three-week doctors’ strike; this past year, many Ontario optometrists have been sending some patients to hospital ERs instead of treating them, as a pressure tactic to increase remuneration from the province.)

Another structural issue lies in what medicare actually pays for. Publicly funded care accounts for only around 70 percent of total Canadian health spending. Most prescription drugs, vision care, nursing home stays, and dental care not received in a hospital are paid for by supplemental private insurance, employee health benefits, or patients themselves. André Picard, an award-winning health writer and columnist based in Montreal, recently described Canadian medicare to me as “the least-universal universal health system in the world.” A 2015 poll suggests that nearly a quarter of Canadians neglected to fill or renew a prescription that year because they couldn’t afford the drugs. In my own case, the plethora of painkillers and blood thinners I had to buy while undergoing cancer treatment would have easily cost thousands of dollars without the generous health benefits offered by the college where I teach.

Is Two-Tier Health Care the Future?, edited by the law professors Colleen M. Flood and Bryan Thomas, gathers a dozen papers by health experts and researchers from Canada and elsewhere to examine one of the central points of conflict in medicare’s funding model. The CHA establishes what is essentially a public monopoly on health care, at least in the areas of care that it covers. Private clinics and labs abound, but they are prohibited from charging a patient for services otherwise covered by the system. This means that anyone with the means to pay for “premium” care is technically unable to do so, unless they travel to another country (or are a pro athlete who has access to a team doctor).

Flood and Thomas’s book explores this issue against the backdrop of a court challenge launched by Dr. Brian Day, a prominent British Columbia orthopedic surgeon and longtime advocate for greater access to private insurance and treatment. Since 1996, Day has been running a for-profit surgery clinic in Vancouver that openly violated both the spirit and the letter of provincial and federal legislation, with officials mostly turning a blind eye. His lawsuit argues that rules prohibiting Canadians from paying for treatment otherwise covered by medicare is a violation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Day and his supporters were essentially calling for the creation of a private option, even as the US struggles to build a public one. (BC’s Supreme Court ruled against Day in early September.)

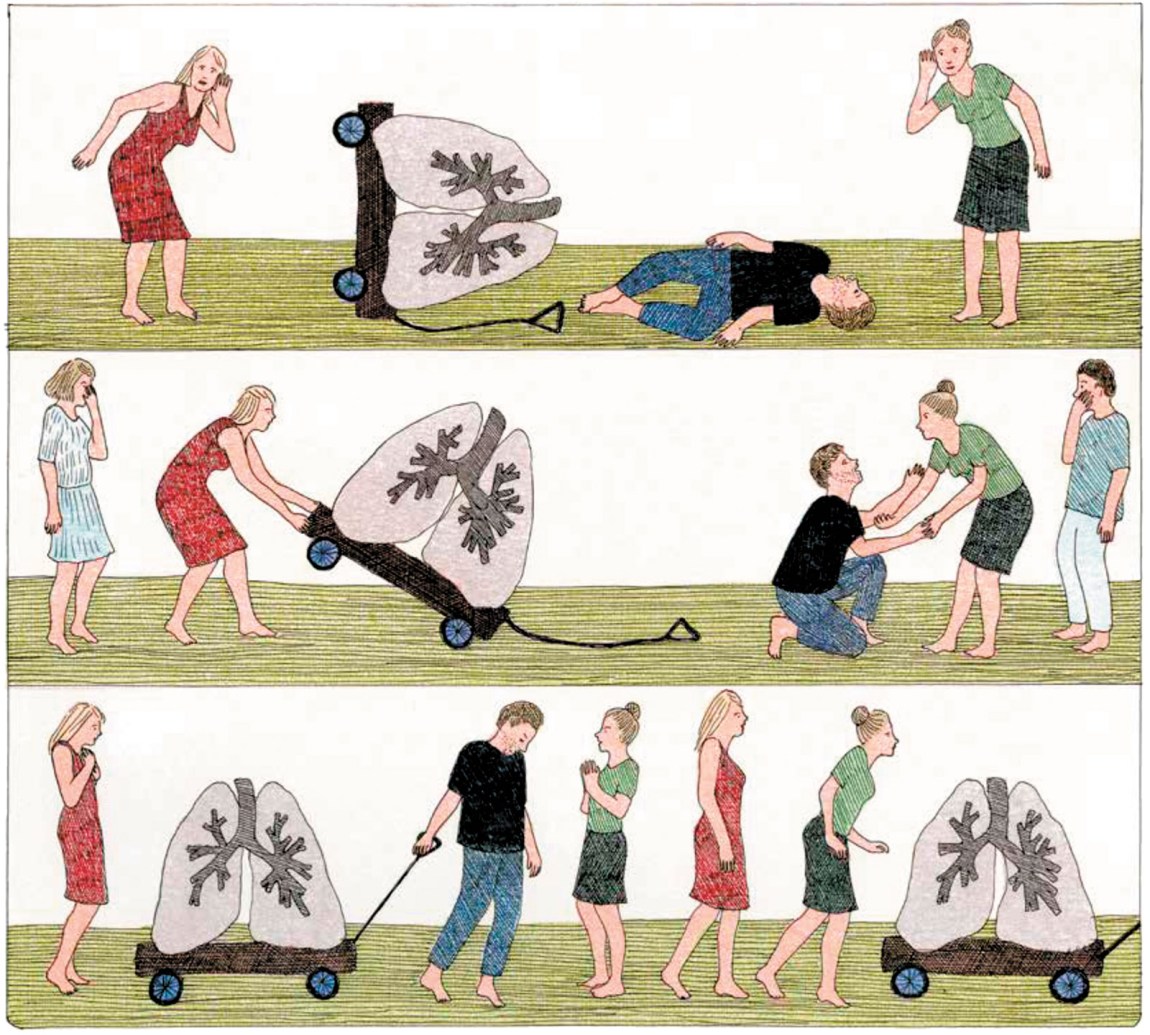

Philpott—who, as health minister, urged the BC court to give the federal government intervenor status in the provincial case, arguing that the country as a whole has a stake in the outcome—says that a ruling in Day’s favor “would have implications for putting the entire Canada Health Act at risk.” If the court decision ultimately forced federal and provincial governments to allow doctors and clinicians to charge for publicly funded care, then many medical practitioners would prioritize their private customers, practice “cream-skimming”—that is, choosing to treat patients based on their ability to pay—or they would leave the public system altogether, aggravating a doctor shortage that already exists in more remote parts of the country. Patients who could afford to get care outside the public system could demand to stop funding that system with their tax dollars, and public support for medicare would have to come from less-well-off patients stuck in a degraded system. Allowing two-tier health care would thus create a kind of medicare death spiral—one that some provincial governments, looking to solve a budget crunch, might be only too happy to help bring about. The Canada Health Act, after all, only requires “reasonable access” to publicly funded health care.

Flood and Thomas are not dispassionate observers in this debate. In their introduction they describe as a “logical fallacy” and “magical thinking” the notion that

because some high-performing European systems allow “two-tier care”—a concept defined so loosely as to be almost meaningless—there is no drawback in Canada’s abandoning its hard-won commitment to single-tier care.

Their book dives deep into the historical and legal basis for Day’s case, the history of Canada’s regulations around private health financing, and the lessons provided by Britain, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Australia, and Ireland—all of which, unlike Canada, allow some sort of private health insurance to exist parallel to the public system. These case studies from abroad suggest that private and public systems do not always coexist easily, and even where they do (as in Germany and the Netherlands), they are so rooted in those countries’ political and social histories as to serve as a poor model for Canada.

Calls to privatize parts of the Canadian system have been understandably muted this year: the Covid-19 pandemic has been, on the whole, handled well by Canadian political leaders and health officials, especially in comparison to the US; as many people have died in Illinois alone as in all of Canada. The case for the reform, and even the expansion, of Canadian medicare has become more urgent, however, as the system’s gaps have become more obvious.

Where the virus has done the most damage so far is in Canada’s private, for-profit nursing homes: a study in late June found that more than 80 percent of the country’s deaths from Covid occurred in long-term care facilities. At least twenty-five such facilities in Quebec and Ontario lost more than 30 percent of their residents to the disease, with some losing up to 40 percent. The nearly two million indigenous peoples in Canada are also poorly served by the country’s health care system, with rates of suicide, infant mortality, and chronic disease that are much higher than those of the nonindigenous population.

How do such gaps and problems persist? Part of the problem, ironically, is the system’s high approval ratings: with such enthusiasm for the existing system, and with responsibility for it shared between federal and provincial or territorial governments, it’s easy for officials to avoid making necessary changes. Picard sees our narrowness of perspective as a big obstacle to reform: “Canadians are also incredibly tolerant of mediocrity because they fear that the alternative to what we have is the evil US system.” Philpott agrees that Canadians’ tendency to judge our system solely against that of the United States can be counterproductive. “If you always compare yourself to the people who pay the most per capita and get some of the worst outcomes,” she told me in a recent Zoom call, “then you’re not looking at the fact that there are a dozen other countries that pay less per capita and have far better outcomes than we do.”

Looking for solutions beyond the binary debate of Canada vs. the US is the central aim of Better Now by the Toronto physician, hospital administrator, and medicare advocate Danielle Martin, who gained fame in 2014 when she sparred with North Carolina senator Richard Burr as part of a health care panel convened by Bernie Sanders. Martin’s confident dismantling of Burr’s smirking attacks on Canadian medicare was catnip for progressives and made her a kind of spokesperson for the benefits of a single-payer system.

Better Now provides an approachably non-wonky summary of some of the problems with medicare that Burr raised in 2014, and offers evidence-driven solutions for each—none of which involves privatization: “The challenges we face—long waits, an aging population, unaffordable drug costs, increasing utilization without much improvement in health—can all be solved within a publicly funded system.” Martin pushes for a national pharmacare program, which she calls “medicare’s unfinished business,” and a greater emphasis on relationship-based primary care, as opposed to relying on specialists—both ideas that have become common among mainstream medicare reformers. She shows how government’s tendency to fix things with more cash can be counterproductive, and argues that the system, for all its gaps, needs to stop overtreating people—to stop throwing tests and pharmaceuticals at illnesses the way politicians throw cash at larger, systemic health care problems.

With its aspirational tone and preponderance of anecdotes about the author’s patients, Better Now sometimes feels like the prelude to a leap into electoral politics, but Martin’s approach is not driven by ideology, and she is quick to point out the specific ways the system is broken. Where the book goes beyond basic reforms is in arguing for a nationwide Guaranteed Basic Income, declaring that “the biggest disease that needs to be cured in Canada is the disease of poverty.” This is where the book is at its boldest and most surprising. Here Martin’s otherwise moderate approach echoes the broader and more sweeping ideals of the early-twentieth-century health care reformers profiled in Radical Medicine, who saw that health is about more than just the way doctors do their billing or how patients receive treatment, as well as the arguments in Is Two-Tier Health Care the Future?, in which the editors maintain that the structure of medicare should reflect what is best for Canadian citizens, not what is easier on government budgets or more likely to survive a court challenge.

“I don’t mind being a symbol,” Tommy Douglas once said, “but I don’t want to become a monument.” Monuments can only be toppled, not changed. Canada’s single-payer health system, that grand symbol of Canadian virtue, possesses numerous gaps and vulnerabilities that threaten to undermine it. In order to survive, the system must be examined, questioned, and reformed. Virtue is nice, but virtue without ambition can lead to outcomes that aren’t worth celebrating—a lesson that Canadians frequently ignore.

This Issue

November 19, 2020

Things as They Are

Grand Illusions of the West

-

*

See David Oshinsky’s review in these pages, “Health Care: The Best and the Rest,” October 22, 2020. ↩