About halfway through the Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas by the Brazilian writer Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis, the eponymous narrator complains, “the main problem with this book is you, the reader.” His style of narration, he suspects, has exasperated even those who have made it this far:

You’re in a hurry to get old, and the book progresses slowly; you love direct, sustained narrative, a regular, fluid style, whereas this book and my style are like a pair of drunkards: they stagger left and right, start and stop, mumble, yell, roar with laughter, shake their fists at the heavens, then stumble and fall…

Brás himself is in no hurry; he’s composing the book from beyond the grave—“not so much a writer who has died, as a dead man who has decided to write.”

Digressive, playful, and irreverent, the Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas was serialized in 1880 and published as a book in 1881. Though Machado, Brazil’s most celebrated writer, is not widely known in the US, generations of Anglophone critics have praised his work, especially Brás Cubas, often lamenting its obscurity among the reading public. Susan Sontag suggested thirty years ago that the novel, first translated in 1952 with the “rather interfering title” Epitaph for a Small Winner, “is probably one of those thrillingly original, radically skeptical books which will always impress readers with the force of a private discovery.” “Perhaps,” she wrote, “some books need to be rediscovered again and again.”

Two new translations, one by Flora Thomson-DeVeaux and the other by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson, are the first to appear in over twenty years.1 Thomson-DeVeaux’s comes with thirty pages of helpful endnotes that offer explanations of Brás’s arcane literary and historical allusions, as well as deleted passages from early versions of the novel. She likens her work to “an apprenticeship, spent staring at a deft-fingered master and doing my best to replicate his tricks,” but she sometimes gets bogged down in revealing the secrets of these prestidigitations, justifying, for example, her choice of the word “flick” over “fillip” or “snap of the/my finger[s],” or her reasons for maintaining the cognate “hypochondria” even though the term has “drifted” from its archaic meaning of “melancholy.” Patterson and Jull Costa’s translation is the more fluid of the two—Jull Costa has elsewhere stated that her goal is to render a writer’s “meaning and…image[s] into meaningful, tangible, sensuous English”—and includes a number of useful, less intrusive footnotes. Readers can’t go wrong with either edition.

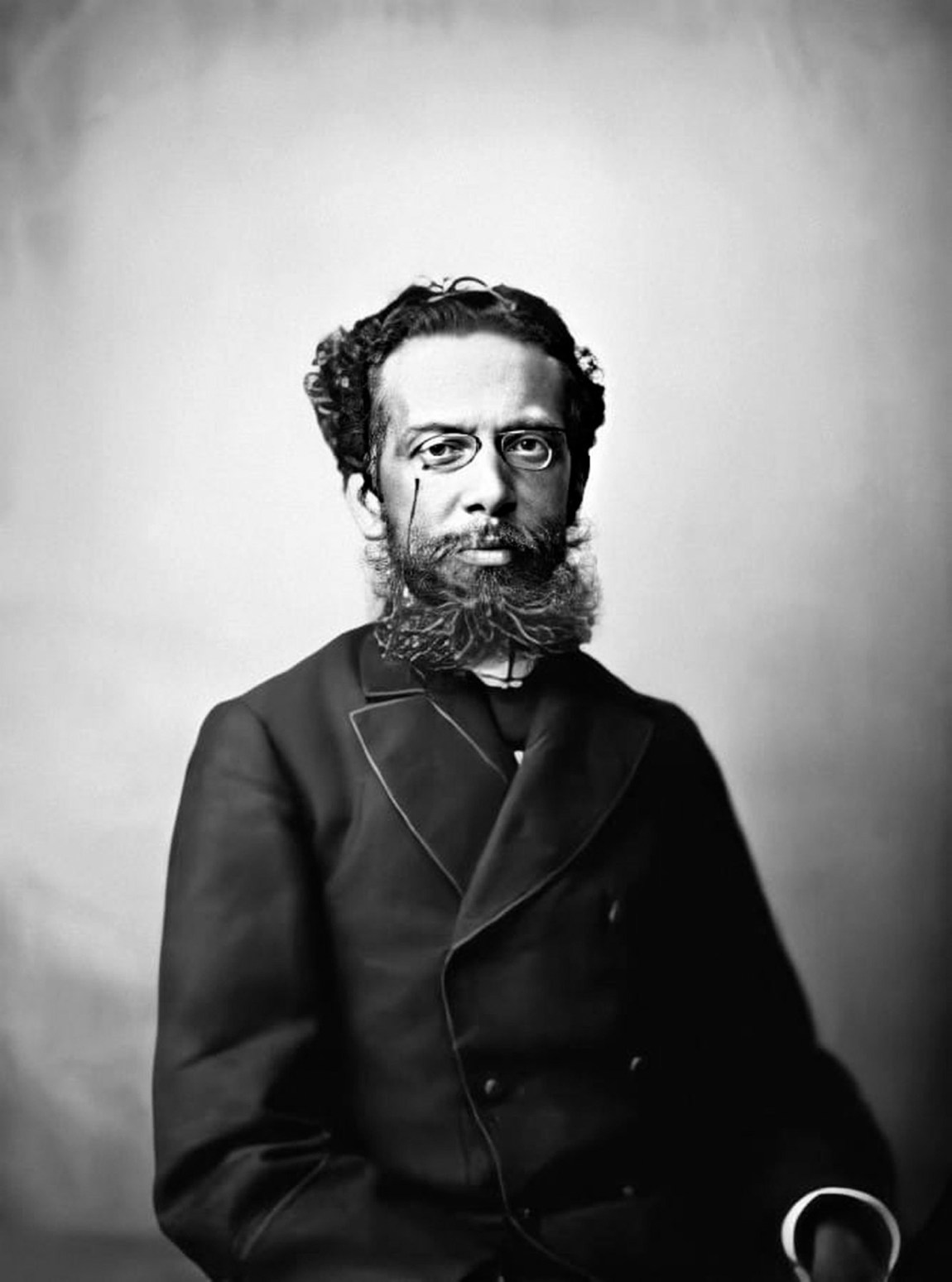

Machado de Assis, born in Rio de Janeiro in 1839, was the son of a mixed-race housepainter, himself the son of freed slaves, and a poor Portuguese woman from the Azores. The family lived on an estate owned by a senator’s widow, who served as Machado’s godmother. It’s said that as a boy he learned Latin from a priest and French from an expatriate baker. In his teens he started working as a typesetter and proofreader, and began publishing poems and articles in newspapers—the scholar Christine Costa wrote that Machado entered “the great halls of literature through the service entrance of journalism.”

In 1869 he married the Portuguese immigrant Carolina de Novais over her family’s objections (which were likely race-based), and four years later he began working for the Ministry of Agriculture, Commerce, and Public Works, eventually becoming the director of the ministry’s accounting department. As his biographer Helen Caldwell wrote, “Practically all the Empire’s bills, that is, demands for payment—and later the Republic’s—passed across his desk. He served the Ministry almost thirty-four years, under thirty-six ministers.”2

During this time he wrote more than two hundred short stories, ten novels, poetry, plays, and hundreds of short pieces for newspapers. Machado became the first president of the Brazilian Academy of Letters in 1897, and he received a state funeral after his death in 1908. Despite his reputation as “the Wizard of Cosme Velho”—referring to the tony Rio neighborhood where he and Carolina lived—the profession listed on his death certificate was “civil servant.”

Machado’s first four novels—Resurrection (1872), The Hand and the Glove (1874), Helena (1876), and Iaiá Garcia (1878)—all center on the love lives of young people in Rio’s middle and upper classes. They hardly prepare one for Brás Cubas, though they share some stylistic aspects of his later work: erudite references and quotations, direct addresses to the reader, and a concern with the meaning of love and marriage in a patriarchal society where many unions were arranged. While most of his stories and novels from the 1870s are written in a refined, lightly satirical tone, by the end of the decade his satire was indicting Brazilian society with devastating and unrelenting wit.

Advertisement

Brás Cubas channels in longer form the adventurous spirit of his short stories from this period, in which well-to-do residents of Rio converse with an ancient Greek statesman (“A Visit from Alcibiades”) or report on their discovery of a society of talking spiders (“The Most Serene Republic”), Satan starts his own religion only to find the faithful rebelling against him by “secretly practicing the old virtues again” (“The Devil’s Church”), and a doctor sends four fifths of the population of a village to an insane asylum before realizing that the sane are actually the ones who should be locked up (“The Alienist”).3 In “How to Be a Bigwig” (which has also been translated as “Education of a Stuffed Shirt”), a father instructs his son on the secret to success, laying bare the hypocrisy and fatuity of the elite:

You, my son, if I am not mistaken, seem to be endowed with the perfect degree of mental vacuity required by such a noble profession [i.e., being a bigwig]…. It is not, however, inconceivable that, with age, you may come to be afflicted with some ideas of your own, and so it is important to equip your mind with strong defenses…. Gin rummy, dominoes, and whist are all tried and tested remedies…. I recommend billiards to you only because the most scrupulously compiled statistics show that three-quarters of those who wield a billiard cue pretty much share the same opinions as the cue itself.

This is the world Brás Cubas enters upon his birth in 1805. The most important forces in his life are public opinion and the pursuit of pleasure, typified by his two uncles: one a Catholic priest who “did not see the real substance of the Church…[but] only the outer skin, the hierarchy, the grandeur, the surplices, the bowing”; the other a former soldier who tells his young nephew “anecdotes…all tainted with obscenity or filth” and flirts with the family’s female slaves. Brás’s father, a wealthy landowner with aristocratic pretensions, dotes on his son while expecting great things of him: “I didn’t invest all that money, time, and effort in order for you not to shine as you should and as befits both you and us. You must carry on the family name and add still more luster.” Brás lovingly mentions the women of his childhood—his aunt and mother—but does not discuss them at length, claiming that “what matters is the general tone of my home life,” which “consisted in a basic vulgarity of character, a love of glittering appearances, noise, and disorder, a general weakness of will, the triumph of the capricious, and so forth. It was from that soil and from that dung that this flower was born.”

Unsurprisingly, Brás is a cruel, spoiled child, riding Prudêncio, a male slave, as if he were a horse and playing pranks on dinner guests. At seventeen he becomes involved with Marcela, a Spanish courtesan who “loved me for fifteen months and eleven contos de réis”—as Thomson-DeVeaux estimates, a few hundred thousand dollars today. Fearing disgrace, Brás’s father sends him to university in Portugal. When he returns, his father arranges a marriage between him and Virgília, ten years his junior and the daughter of a well-connected politician. Brás is attracted to the possibility of attaining “fame and reputation” with the help of Virgília’s father, but she—“a proper little imp, an angelic imp if you like, but an imp nonetheless”—aspires to a noble title. Brás’s rival, the ambitious Damião Lobo Neves, promises to make her a marchioness, and she marries him:

Virgília compared eagle and peacock and chose the eagle, leaving the peacock with nothing but his surprise, his indignation, and the three or four kisses she had given him. Possibly five, but even if there had been ten, it wouldn’t have meant a thing.

The shock of the canceled engagement kills Brás’s father, and after a squabble over the inheritance, Brás falls out with his sister, Sabina, and her husband, Cotrim. Adrift, he spends the next ten years “allowing myself to be carried along on the back-and-forth of events and days…. I wrote about politics and dabbled in literature…and even acquired a certain reputation as a polemicist.” In 1842 he runs into Virgília at a ball; although they “were essentially the same” as they had been during their courtship, that earlier moment “clearly wasn’t opportune,” but “the opportune moment had now arrived.”

The two begin a long affair, renting a house in an out-of-the-way neighborhood to avoid suspicion. After Virgília gets pregnant and Lobo Neves receives an anonymous note claiming that Brás is the father, Brás relishes “the salt of mystery and the pepper of danger,” believing that risk will strengthen Virgília’s passion for him. But just as he thinks their love is at its most intense, she pulls away, concerned about her reputation and her husband’s wrath—and no doubt still considering her paramour to be a peacock. “You don’t deserve the sacrifices I’m making for you,” she tells Brás, recoiling from his embrace “as if from the kiss of a dead man.” Virgília suffers a miscarriage, and when, some months later, Lobo Neves appears unannounced at the love nest, Brás concludes that the affair has been overseasoned.

Advertisement

Virgília and Lobo Neves leave Rio for a political appointment in another province; Brás reconciles with his family and becomes a disciple of Quincas Borba, an old schoolfriend whose philosophical system, Humanitism, “easily accommodated itself to the pleasures of life, including those of the table, the theater, and the flesh.” Promising to be the caliph to Borba’s Muhammad, Brás runs for office, but he cuts a mediocre figure in Parliament, giving a single speech in which he calls for the size of soldiers’ hats to be reduced, since “the shako, by its sheer weight, bowed the heads of our citizens, whereas the nation needed citizens who could hold their heads up proudly.” In his late forties he makes one last bid for love, but his nineteen-year-old fiancée, Eulália, a distant cousin of his brother-in-law, succumbs to yellow fever in an epidemic.

Quincas Borba goes mad and dies. Brás, as he tells us in the book’s first chapter, expires in 1869 from pneumonia he catches while trying to invent what he calls the “Brás Cubas Poultice,” with which he hopes to end human melancholy. In the final chapter, titled “On Negatives,” Brás concludes, “I did not achieve fame through my poultice; I did not become…a caliph; I never married.” But in death he finds himself “with a small positive balance…: I did not have children, and thus did not bequeath to any creature the legacy of our misery.” He dedicates his memoirs “to the first worm to gnaw the cold flesh of my corpse.”

The memoirs are written in 160 short chapters, some just a few sentences long. (Here is chapter 136 in its entirety: “But, unless I am much mistaken, I have just written an utterly pointless chapter.”) Others consist only of an epitaph or, in the case of the chapter called “How I Did Not Become Minister of State,” rows of mute periods. The narrator—who says early on that he’s inspired by the “free form” of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy and Xavier de Maistre’s A Journey Around My Room—frequently interrupts his account of his life, providing anecdotes and illustrations to explain the characters’ psychology or positing laws about human nature.

In these charming asides, Brás condemns his own behavior and defends it, often at the same time, admitting to a peccadillo in order to avoid responsibility for his graver sins. He himself alerts us to this strategy, which he calls “the famous law of the equivalence of windows.” For example, his trepidation about starting an affair with Virgília is abated because of the praise he receives after finding a half doubloon on the street and sending it to the police department instead of keeping it himself:

My conscience had waltzed so much the previous evening that she had been left breathless and panting; but the restoration of that half doubloon opened a window onto the other side of morality; in rushed a gust of pure air, and the poor lady, my conscience, breathed more easily. Readers, always keep your consciences well ventilated!

When, a few days later, he comes across a box containing a vast sum of money, the memory of the returned half doubloon makes it possible for him to keep the box without compunction.

Brás, like the best nineteenth-century dandies, finds particular delight in taking contrarian, even perverse positions on morality—and morality for him is largely a matter of public opinion. “This terrifying public opinion, which is always so curious about bedrooms,” threatens one with ostracism and shame for one’s misdeeds, but Brás also acknowledges that, by keeping desire in check, public opinion serves as “an excellent solder for domestic institutions,” binding man and wife if only out of fear of scandal. Pleasure can be found in unlikely and even unpleasant sensations, since the more obvious ones are often too perilous to attain:

The voluptuousness of tedium: remember that expression, dear reader; store it away, scrutinize it, and if you fail to understand it, you may conclude that you have never yet experienced one of the most subtle sensations of this world.

When we cannot satisfy the demands of desire or public opinion, Brás tells us, we can always resort to self-love: a man who has been outdone by a rival “feels mortified, but, with eyes cast down or looking straight ahead he walks on, pondering his rival’s prosperity and his own failure to thrive…. It is at this point that he fixes his eyes on the tip of his nose.” Simply possessing a unique identity, Brás suggests, provides a salve for a wounded ego and a basis for believing in one’s superiority: “In conclusion, there are two main forces: love, which multiplies the species, and the nose, which subordinates the species to the individual.” (As in Tristram Shandy, “nose” almost certainly refers both to a nose and to a different appendage.) Even as Brás’s own nose disintegrates “here in the next world,” his pride in it remains.

Should we take Brás’s philosophizing as an attempt to explain away his failures, as the occasionally profound witticisms of a wag, or as something more sinister? In A Master on the Periphery of Capitalism,4 the Brazilian critic Roberto Schwarz argued that the tone and form of Brás Cubas reflected the capriciousness of Brazil’s plantation-owning ruling class, which throughout the nineteenth century was torn between its reverence for liberal European culture and its own illiberal economic interests (Brazil was the last Western country to outlaw slavery, in 1888). “From the practical perspective,” Schwarz writes, “slavery was a contemporary necessity; from the emotional perspective, a traditional presence; and from the ideological perspective, an archaic disgrace.”

Unable to reconcile their theoretical commitments with the domination—not only of slaves but also of free laborers in a slave economy—required to maintain their status, wealthy Brazilians pursued, Schwarz writes, a sort of “clowning elitism…a self-congratulatory, exclusive irresponsibility…a cult of dilettantism and of the self.” Brás, whose family’s fortune rests in planting, similarly tries to distract from the material conditions that undergird his life, tying “the reader down to the minutiae and mak[ing] it difficult to picture the wider panorama.”

The most pernicious, and absurd, defense of the status quo comes from Quincas Borba, who believes that oppression is necessary, and even a virtue. His philosophical “system,” Humanitism, a sort of parody of Social Darwinism and Positivism, asserts that “struggle is the main function of the human species” and “all forms of bellicose feelings are conducive to happiness”:

War, which seems a calamity, is a useful operation, which we might call Humanitas cracking its knuckles; hunger (at this he sucked philosophically on the chicken wing), hunger is a test to which Humanitas sets its very entrails.

Humanitism even accounts for how that chicken got to Borba’s plate:

It was fed on corn, which was planted by, let’s suppose, an African imported from Angola. This African was born, raised, and sold; a ship brought him here, a ship built of wood cut from the forest by ten or twelve men, and propelled by sails sewn by a further eight or ten men…. Thus, this chicken…is the result of a multitude of efforts and struggles undertaken with the sole aim of satisfying my appetite.

To Quincas Borba, “pain was an illusion, and…Pangloss, the much-maligned Pangloss, was not as foolish as Voltaire supposed.” Humanitism, Schwarz writes, amounts to “an enlightened justification [for] the indifference of the rich toward their dependents.”

Brás sees Humanitism’s savagery while recognizing its appeal, especially to those with guilty consciences, but eventually he rejects it. “Please note,” Brás says after giving up his political aspirations, “that Quincas Borba discovered, by a process of philosophical deductions, that my ambition was not a genuine passion for power, but a mere whim, a desire for amusement.” Despite seeing through the cant of the class to which he belongs, Brás himself gives a somewhat less enlightened justification for his brother-in-law, Cotrim, who smuggles slaves into Brazil after the trade was outlawed in 1850 and who has a reputation for “frequently sending slaves to the calaboose, from where they would emerge dripping with blood.” “Proof of Cotrim’s compassion,” Brás insists, “can be found in his love for his children,” his membership in charitable organizations, and the fact that “he didn’t owe a penny to anyone.” Per the law of the equivalence of windows, Cotrim’s conscience must have a healthy draft running through it.

During his lifetime Machado was criticized by abolitionists for not condemning slavery, with one critic writing, “Hate him, because he is evil; hate him because he hates his race.” Slaves in his fiction are often dutiful servants or interlopers who masters worry are spying on and gossiping about them.

Machado in fact deeply opposed slavery, but with the exception of a few chilling short stories composed after emancipation, he published his most impassioned antislavery writings anonymously, perhaps to avoid professional repercussions, since the agriculture ministry that employed him was responsible for carrying out laws relating to slavery. He was careful to conceal his criticisms of the elite under layers of irony, all the more so because of his ethnicity. The sociologist G. Reginald Daniel writes that “mulattoes [in nineteenth-century Brazil] had social advantages over blacks, which increased their chances of upward mobility,” but those advantages were still precarious. Daniel suggests that “this also helps explain their silence on the question of racism, which kept them in a position of second-class citizenship during slavery.”5

Yet Machado’s fiction, contrary to the views of his contemporary critics, does denounce slavery. As Daniel writes, “slavery provides an important and seething backdrop in Machado’s writings.” The institution dehumanizes all who come into contact with it: slaves, masters, and masters’ accomplices alike. Sometimes slavery enters the foreground, as when Brás sees Prudêncio, the slave he abused as a boy, whipping a black man in a Rio street. Prudêncio was freed by Brás’s father, and the man he is beating is his own slave. Prudêncio replies to the groans of pain with the same words Brás said to him thirty years earlier: “Shut your mouth, you animal!” Brás believes that the whipping

was Prudêncio’s way of ridding himself of all the beatings he had received, by passing them on to someone else. As a child, I had ridden on his back, put a bridle between his teeth, and thrashed him mercilessly; he could do nothing but groan and suffer. Now that he was a free man…he had bought a slave and was paying him, with hefty interest, for all that he had received from me.

After this epiphany, Brás expresses a sort of pride at his former mount: “See what a clever rascal he was!” As in his praise of Cotrim, Brás’s chummy approval masks the author’s condemnation of a society that permits people to behave like beasts, and then to accuse their victims of being the true brutes.

Though Schwarz contends that Brás’s allusive, digressive style satirizes the asininity of the Brazilian upper classes, there’s a closer target of Machado’s wit: the author himself. He shares with Brás a love of historical and literary allusion, a compulsion to compose aphorisms, and a delight in extended metaphors and fanciful anecdotes even, sometimes especially, if they shed no light on the topic under discussion. Brás Cubas indulges and amplifies Machado’s playful pedantry. In one four-paragraph-long chapter, he manages to squeeze in references to Suetonius, Seneca, the Battle of Salamis, the Augsburg Confession, Emperor Claudius, Lucrezia Borgia, Oliver Cromwell, and Bismarck; this passage is notable in its pomposity and the disarming effect it has on the reader, but it’s not atypical of Machado’s fiction. His obscure allusions (he read at least six languages), reflecting an autodidact’s pride in beating the stuffed shirts at their own game, have sent scholars scrambling to uncover hidden meanings and track down references to long-forgotten texts.

That Machado imbues Brás with his own wit and charm complicates the satirical nature of the novel; along with the accusatory tone Brás sometimes takes toward his audience, his appeal reminds readers of the thousands of ways, large and small, they account for their behavior and their place in an exploitative society. Indeed, Machado, the assiduous civil servant, must have recognized his own complicity with the Brazilian slave economy and confronted the dead end of self-exculpation.

Machado’s later work, which is less disputatious than Brás Cubas, suggests that solace can be found in the simple pleasures of friendship, honesty, and hard work, but it’s no less trenchant. His characters’ attempts to rationalize their actions with lofty ideas are always devastatingly deflated, as when Brás, in one of the most astounding passages of the novel, recounts the “delirium” he experiences shortly before his death. Carried to the beginning of time on the back of a talking hippopotamus, he meets Nature, a giantess who also calls herself Pandora, “because my bag contains all that is good and evil, including the worst evil of all, hope, mankind’s great consolation: hope.” On a mountaintop they watch “a procession of all the centuries”:

There was devouring greed, incendiary rage, drooling envy, the hoe and the pen—both damp with sweat—as well as ambition, hunger, vanity, melancholy, wealth, and love, all furiously rattling mankind as if we were a tinkling cowbell.

Brás concedes to Nature that the pageant “is funny and definitely worth seeing, a touch monotonous perhaps, but still definitely worth seeing.” It’s tempting to read this as a comment on Machado’s own work: his frequent toggling between the particular and the universal, between description and aphorism, can be alternately brilliant and banal, tiresome even when it works well, but nowhere in his writing does he pull it off as impressively as he does in Brás Cubas. That talking hippopotamus, as the delirium subsides, “began to shrink and shrink and shrink, until it was the size of a cat. In fact, it was a cat. I took a closer look; it was my cat Sultão, who was playing with a ball of paper at my bedroom door…”

This Issue

December 17, 2020

An Awful and Beautiful Light

The Oldest Forest

-

1

The most recent was by Gregory Rabassa (Oxford University Press, 1997). Michael Wood reviewed it and the other novels by Machado included in the Library of Latin America series published by Oxford University Press—Quincas Borba, Dom Casmurro, and Esau and Jacob—in these pages, July 18, 2002. ↩

-

2

Helen Caldwell, Machado de Assis: The Brazilian Master Writer and His Novels (University of California Press, 1970). ↩

-

3

These tales are all included in The Collected Stories of Machado de Assis, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson (Liveright, 2018). An abridged, more digestible (and portable) version, 26 Stories, was published as a paperback last year. About a hundred of Machado’s stories have yet to be translated. ↩

-

4

Translated and with an introduction by John Gledson (Duke University Press, 2001). ↩

-

5

See G. Reginald Daniel, Machado de Assis: Multiracial Identity and the Brazilian Novelist (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012). Daniel’s book provides an incisive discussion of Machado in relation to the history of race, slavery, and literature in Brazil, and it is also a fine general introduction to the writer’s work and his English- and Portuguese-language critics. For Machado’s anonymous antislavery writings, see “Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis: Six Crônicas on Slavery and Abolition,” translated and introduced by Robert Patrick Newcomb, Portuguese Studies, Vol. 33, No. 1 (2017); and Good Days!: The ‘Bons Dias!’ Chronicles of Machado de Assis (1888–1889), translated by Anna Lessa-Schmidt with Greicy Pinto Bellin (New London Librarium, 2018). ↩