“What portion in the world can the artist have,” asked Yeats, “but dissipation and despair?” Hans Schnier, the professional clown of Heinrich Böll’s new novel (the sixth to be published in America), doesn’t take to dissipation—he is an innocent, a pure person, irretrievably monogamous, and cognac costs money—nor completely to despair. The novel ends with him begging outside Bonn Railroad Station, the first coin falling into his hat. Charity? He is singing for his supper. And rather the charity of passing individuals than a retainer, a grant, a subsidy. For this way no group, no institution, no party is buying the clown and his services.

The novel begins with the twenty-seven-year-old clown arriving in Bonn, down on his luck, with a swollen knee and without his beloved Marie. The Catholics have seduced Marie away from him, persuaded her to marry one of Them and thus (in Schnier’s view) to commit adultery, double adultery even, since (he tells himself) she will surely return to him one day. Alone in his room, between telephone calls to various acquaintances who might be able to help him, he recalls the past. Such is the form of the novel.

Lacking action in the usual sense of the word, The Clown yet moves with a remarkable purposiveness, its constituents working singlemindedly together. Possibly for this reason it may not prove altogether acceptable. The sensitive contemporary reader prefers to be knocked flat by a velvet glove and there is perhaps too much iron in evidence here. I think it is the case that the irony is rather too insistent. So many of Schnier’s acquaintances have suffered a postwar sea-change into something not so strange though certainly rich enough. His mother, once so zealous that the “Jewish Yankees” should be driven from “our sacred German soil,” is now president of the Executive Committee of the Societies for the Reconciliation of Racial Differences and “lectures to American women’s clubs about the remorse of German youth.” Brühl, a schoolteacher of Blood-and-Soil tendencies, is now a professor at a Teachers’ Training College, a man known for his “courageous political past”: he never actually joined the Nazi Party. Schnitzler, instrumental in forcing the young Schnier into the Hitler Youth, wrote a bad novel about a fairhaired French lieutenant and a darkhaired German girl which incurred the displeasure of the National Socialist Writers’ Association (a careless use of the palette) and caused him to be suspended from writing for some ten months: the Americans welcomed him as a resistance fighter, “gave him a job in their cultural information service, and today he is running all over Bonn telling all and sundry that he was banned under the Nazis.” These are people with whom (it is made plain, plainer than necessary) you cannot communicate. You ask them a personal question and you get a party answer. They do not help lone clowns.

Böll takes his epigraph from Romans XV. “To whom he was not spoken of, they shall see: and they that have not heard shall understand.” Paul had been preaching the gospel where Christ’s name was unknown, where he could not build upon another man’s foundation. Schnier is a gifted mime, he could make an excellent living in Leipzig with his “Cardinal” or “Board Meeting” turn, and in Bonn with his “Party Conference Elects its Presidium” or “Cultural Council Meets” act. But the trouble is, he wants to do the latter numbers in Leipzig and the former in Bonn: he has no “audience-sense.” “To poke fun at Boards of Directors where Boards of Directors don’t exist seems pretty low”: and the same with Elections of Presidiums. There is an obvious parallel here with Schrella’s story in Böll’s previous novel, Billiards at Halfpast Nine. A refugee from the Nazis, Schrella was imprisoned in Holland for threatening a Dutch politician who said that all Germans ought to be killed. When the Germans came in they freed him, a martyr for Germany, but then realized that he was on their list of wanted persons, so he had to escape to England. In England he was imprisoned for threatening an English politician who said that all Germans should be killed and only their works of art saved. The clown’s job is not to confirm but to disturb, to preach to the unconverted. Böll’s further gloss on the text from Romans would seem to have it that in the world as it is real Christian feeling exists outside the Churches, real socialism outside the socialist parties, real concern for racial harmony and real chances of it outside the Executive Committee of the Societies for the Reconciliation of Racial Differences…And, perhaps, real married love outside the marriage certificate.

Schnier then is an active non- or antiparty man, not merely an elegant ironist on the side-line. How he behaves as an artist consorts exactly with how he feels as a man. Art should be free—but that doesn’t mean that art exists for the sake of art. He abandons a highly successful number called “The General”—perhaps this makes him no artist at all?—because after the first performance he is visited by the widow of a general killed in battle, “a little old woman.” There are generals who are good men, or there are good widows of generals, or pathetic little old women. Similarly, however bitterly Schnier feels the defection of Marie, he admits that there are Catholics who are good men; indeed he admires Pope John immensely. It is Catholicism he is against, the party line, the party men, the people who begin sentences with the words, “We Catholics,” just as he is against those who begin their sentences, “We Protestants…,” “We Atheists…,” “We Socialists…” “We Germans…,” and so forth. He will never be a “great satirical artist,” because he refuses to generalize, because “strangely enough I like the kind to which I belong: people.” Life is indeed hard for a clown unless he is prepared to toe a Clown party line of one sort or another.

Advertisement

The rhetorician seeks to deceive his neighbors, Yeats said, the sentimentalist to deceive himself. Böll deals nicely with his rhetoricians, but his clown is something of a sentimentalist, perhaps, a little too sorry for himself. In his lament for Marie he grows maudlin: a clown should be able to cut his losses, to shoulder a broken heart and march on. But the sorrows of unrequited monogamy are a rare phenomenon in current fiction, and it may be that our conditioning inevitably makes them seem embarrassing. Elsewhere I am more sure that Böll’s tact has forsaken him. Our sympathies go astray when Schnier informs us that his mother (on whom we are already fully informed) was a ban-the-bomb campaigner for three days until a business friend told her this policy would lead to a slump in the stock market. At times Böll can be strident, as when Schnier thinks of the people who helped Marie and him in their hard times “while at home they sat huddled over their stinking millions, had cast me out and gloated over their moral reasons.” Possibly explicitness of this order, this insistence, is intended as a guard against a self-indulgent or merely self-protective irony, against that habit of “keeping your superiority feelings fresh in a refrigerator of irony,” as a character in Billiards at Half-Past Nine puts it. Böll doesn’t want his novel read as a cosy, remote “allegory,” a mere parable about The Creative Artist in Relation to Church and State in an Age of Technology (to borrow a lecture-title from his earlier book, Tomorrow and Yesterday) or the Condition of Twentieth-Century Man (who is never you or me). Every now and then a clown must be allowed to be very simple and straightforward and unsophisticated.

Böll has something to say, and not of course merely something about the Germans. He says it several times. A common weakness of writers with something to say is their inability to understand that saying it four times is not four times as effective as saying it once. But to have something to say—how rare this is! Unlike Uwe Johnson in Speculations about Jakob, Böll doesn’t erect reading-difficulty into a law; although retaining the flashback technique of Billiards at Half-past Nine, this new novel is less gratuitously involuted, with a positive stylishness of clarity and competency, and free from fussiness. Unlike Günter Grass, Böll doesn’t obscure his real meaning with a barrage of private emblems. Unlike certain British contemporaries, he doesn’t seek to obscure the absence of meaning with an aura of bogus “symbolism,” to disguise as high metaphysics a bedroom farce or an Arabian Nights’ sexual dream. “I would rather read Rilke, Hofmannsthal and Newman one by one than have someone mix me a kind of syrup out of all three,” remarks Schnier apropos of a sermon by an “artistic” prelate. There are few novels coming out these days which aren’t either a kind of syrup or a kind of emetic. The Clown, I have omitted to mention, besides being one of these few, is at times very funny, as well as sad, as well as salutary.

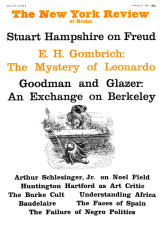

This Issue

February 11, 1965