As the Seattle boat swung up the wharf…the IWW men were merrily singing the English Transport Worker’s song Hold The Fort. When the singers…crowded to the rail…Sheriff McRae called out to them:

“Who is your leader?”

“We are all leaders!”

“You can’t land here.”

“Like hell we can’t!” came the reply…A volley of shots sent [the Wobblies] staggering back…

So began the Everett Massacre of 1916, in which a shipload of Wobblies on their way to contest the right of free speech in a Washington lumber town were shot down by several hundred gunmen, scabs, militiamen, ex-policemen, “and other open-shop supporters.” At dusk of Bloody Sunday, at least five Wobblies had been killed, and thirty-one wounded. But this was the One Big Union, not CORE or SNCC. The toll for the Everett vigilantes, which included “lawyers, doctors, business men…and ignorant university students”: nineteen wounded, two dead.

Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology is a selection, in large part from the Labadie Archives at the University of Michigan Library, of poems, stories, songs, satires, and cartoons. The collection was gathered and kept for years by the millionaire spinster, Miss Agnes Ingles of Detroit. Our debt to her and to the editor of this book is great. Mrs. Kornbluh’s achievement in putting together this anthology seems especially commendable when we consider how difficult it is to reconstruct the subject by the printed word. Indeed, much of the material is anonymous, or signed “By an Unknown Proletarian,” “The Wooden Shoe Kid,” “J. H. B. the Rambler,” “A Paint Creek Miner,” “Scotti,” “Card No. 512210.”

On a June morning, 1905, William D. Haywood—“Big Bill”—then secretary of the Western Federation of Miners, walked to the front of Brand’s Hall in Chicago through a crowd of 200 “socialists, anarchists, radical miners and revolutionary labor unionists,” picked up a piece of loose board and hammered on the table for silence. “Fellow workers,” he said, “this is the Continental Congress of the working class.” It almost was.

Machine technology, and the classwar character of industrial struggles east and west of the Mississippi, had brought tens of thousands of wageworkers to an insubordinate frame of mind. There was no place for most of them in the skilled craft unions of Samuel Gompers’s A.F. of L. By fighting back they had little to lose. Just before the great Lawrence mill strike in 1912, “A report of the U. S. Commissioner of Labor…showed that…textile employees, including foremen, supervisors, and office workers [my italics] averaged about $8.76 for a full week’s work…well over half were women and children.” The Western Federation of Miners, shaken by crushing strikes in Colorado and Idaho, took the lead in trying to find a way out.

The IWW’s purpose was never veiled. Eugene Debs, who had sat on the platform in Brand’s Hall, said “The Industrial Workers is not organized to conciliate but to fight the capitalist class.” Job rights were to be protected on the job, by sabotage (“the conscientious withdrawal of efficiency”) if necessary, as the first and essential step toward the goal of an industrial co-operative commonwealth. The “social general strike” was to be the major weapon in overthrowing the capitalist state. Although there were a number of large local strikes, the threat of a general shut-down was to remain rhetorical except insofar as there may have been, and probably was, indirect influence behind the later San Francisco and Seattle city-wide strikes. Where would the troops come from? “I do not care a snap of my fingers whether or not the skilled workers join…” Haywood shouted at the Chicago meeting. “We are going into the gutter to get at the mass of workers…”

The IWW soon attracted some of the most rugged and independent personalities in America. The famous preamble to the constitution—“The working class and the employing class have nothing in common”—was coined by a renegade Catholic priest, and the three best-known IWW martyrs were a Swedish drifter named Joel Ammanuel Haaglund, otherwise known as Joe Hill, the war veteran Wesley Everest, who was castrated in Centralia, Washington, by American legionnaires, and the half-Indian one-eyed organizer Frank Little, lynched with his leg in a cast outside Butte. Western homesteaders turned hard-rock miners, laborers following the harvest combines of the Great Plains, and savvy immigrants were the principal blood stock of the I.W.W. For socialists too radical, for anarchists too mild, for everybody else impossible, these men constituted, at that time and in that place, the most alienated, game, and aggressive workers in the wage system.

On the job IWWers inclined to be good workers. Initiation fees and dues were low, Negro-baiting prohibited. An immigrant with a paid-up union card in his own country was eligible to join immediately. A system of simple hieroglyphics on fence-posts and front-gates was worked out to indicate the type of welcome that could he expected from local police and housewives. When a Wobbly was sent to jail for speaking (“I’ve been robbed! I’ve been robbed!” one of them would yell, drawing a crowd. “I’ve been robbed by the capitalist class”), within a few days, sometimes hours, the town would be swarming with IWW soap-boxers disposed to get into the same jail. Behind bars they would hold classes, try to educate their guards, and occasionally, for the hell of it, “build a battleship”—that is, lock arms and at the count of three jump up and land on the floor at the same time, causing the frequently frail jail-house structures to rock as though in an earthquake. Riding the “rattlers” and living in railroad-embankment “jungles” was the common mode of existence within the One Big Union.

Advertisement

Within the I.W.W. dissension developed almost immediately between “direct” and “political” actionists. The increasingly conservative Western Federation of Miners fired Haywood and pulled out to rejoin the AFL. But, as Mrs. Kornbluh says, “despite organizational schisms, across the country from Tacoma, Washington, to Skowhegan, Maine, the message of One Big Union, stimulated strikes among loggers, miners, smeltermen, window washers, paper makers, silk workers, and street-car men.” Wobblies staged the first sitdown strike in America at the Schenectady, New York, plant of the General Electric Company in December 1906.

At the 1907 convention, Daniel De Leon, America’s classic ideologue, offended by their lack of sophistication and little knowledge of socialist theory, dubbed the twenty-six delegates the “bummery” because they sang “Hallelujah, I’m a Bum,” and accused them, not without truth, of trying to make the IWW a “purely physical force body.” Eventually the “politicals” were ousted and the IWW could, and did, unreservedly express its disdain of the ballot box, shop contracts, and capitalist legal machinery in general. The fact is, IWW-run strikes were usually highly disciplined, and non-violence was preached and practiced whenever possible. It was not always possible. The membership of the IWW never rose above 250,000, but in the political and industrial life of the United States no group, not even the Communist Party, has been more feared and hated. The reason, on one level, is simple. The IWW aimed overtly to abrogate the basis of American property. But it was not the owners who had the greatest malice towards the IWW (the rich in fact had a certain bloodthirsty respect for it), but America’s shopkeeping and professional class: the Citizens Club luncheaters, the American legionnaires and fraternity boys. (“Our company of militia went down to Lawrence during the first days of the strike. Most of them had to leave Harvard to do it; but they rather enjoyed going down there to have a fling at those people.”)

The reasons for this are not entirely clear. The uncomplicated solidarity—perhaps the love—which one Wobbly felt for another, and his refusal to defer even to the “charismatic” leadership of his own union, were things a Seattle business man or Butte legionnaire could secretly envy. “…you cannot destroy the organization…It is something you cannot get at. You cannot reach it. You do not know where it is. It is not in writing. It is not in anything else. It is a simple understanding between men…” This from Senator Borah, who tried to hang Moyer, Pettibone, and Haywood. Then too there was the Wobbly’s characteristic personal honesty—contracts, when made, were honored. And of course the attractive, lonely footlooseness. But perhaps another, better, reason lies in the fact that it was the revolutionary hobo, the self-proclaimed saboteur, who for a considerable period of our national history was the sole, certainly the most notorious, patron of the national hope to which even the IWW’s most hysterical enemies subscribed. The difference was that the Wobblies held on to it, and for this they could not be forgiven. Rexford Tugwell, a liberal sympathizer, wrote in 1920:

One who has seen the glow of the great Wobbly dream light the faces of the lumberjacks has seen the unforgettable, the imperishable…they plan a new order they will never know…they can dream and dreaming, be happy.

The IWW never recovered from the post-war anti-radical campaign and punishment for conscientious objection during World War I. (Scores of Wobblies turned their backs on President Harding’s offer of a post-Armistice “clemency.” But it was the Depression of 1932 that really finished it. The CIO, the Communist Party, and the New Deal mark the Wobbly graveyard, though the way had long been prepared by Mabel Dodge, John Reed, and the pageant for the Paterson Strike at Madison Square Garden which brought something new and exciting to proletarian art and virtually killed the strike it was meant to support.

Advertisement

The OBUers, who loved children—it stands out in everything they wrote—did not beget descendents. The organization celebrated its fiftieth anniversary unable to engage in collective bargaining anywhere. On a recent visit to the IWW hall in Seattle, an historian, Robert L. Tyler, wrote:

Inside the hall near the door stand two battered roll top desks stacked high with piles of papers and newspapers. A naked light bulb hangs from the ceiling over the desks. In the rear of the hall, several elderly men in work clothes play cribbage at a heavy round table. Against the wall near the door stands a book case, the library of the Seattle IWW branches. A few titles are readily discernible. Marx’s Capital…Gustavus Myer’s History of the Great American Fortunes, Darwin’s Origin of Species and, oddly enough T. S. Eliot’s Collected Poems.

Like the striking mill girls at Lawrence, the IWW wanted bread and roses too.

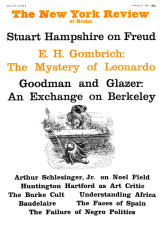

This Issue

February 11, 1965