“We know of no spectacle so ridiculous,” said Macaulay, “as the British public in one of its periodic fits of morality”; and he proceeded to describe, in caustic language, the national tendency to indulge an outraged and “outrageous” virtue at the expense of some unfortunate public man who has been convicted of an indiscretion that snocks its sense of decency. There has been in recent years no better example of these national explosions of “outrageous virtue” than that provoked by the affair connected with Miss Christine Keeler, and the Bishop of Southwork well expressed the feelings of the outraged majority when he told a diocesan conference that “Things have happened in recent weeks that have left an unpleasant smell—the smell of corruption in high places, of evil practices, and of a repudiation of the simple decencies and the basic values,” and declared, in smug and stirring tones, that the time had come “to clean the national stables.” The books under review illuminate the affair from diverse angles: Mr. Charlton’s “Conversations” give us a glimpse through the stable window; Mr. Kennedy, like the Bishop but preaching from a different pulpit, indulges a strong vein of moral indignation; Lord Denning provides a comprehensive survey of the facts.

Looking back upon the whole story, one may very well conclude that vice did reveal itself among those who occupied positions of power, but that the vices and the persons who displayed them were not those at which the moral censors at the time pointed their accusing fingers. The most shameful feature of the affair was the unscrupulous procedure of a number of newspapers which, with an unctuous affectation of highmindedness, propagated rumors that were sure to stimulate the prurience of the public, regardless of the cost to the reputation of innocent individuals, of the Government services, and of the nation itself in the eyes of foreign observers. Let one example stand for many: “PRINCE PHILIP AND THE PROFUMO SCANDAL” was the form of words with which the editor of a daily paper headed a column that loyally contrived at once to “clear” and to smear the name of the Royal Family.

If moral condemnation was called for it was surely on account of such performances as these; and the most interesting ethical problem that was raised by the affair was not to fix a proper standard for the behavior of public men, but to decide how other responsible citizens should react when a public man has apparently fallen short of such a standard. The issue is one that confronts not the erring politician but his critics: what, to put the question in a nutshell, are the circumstances that justify public criticism of private lives?

“Civilization,” according to an acute and liberal thinker, “is a thin and precarious crust erected by the personality and the will of a very few and only maintained by rules and conventions skillfully put across and guilefully preserved.” Whether or not that has always been true of civilization in a large sense, it is certainly the case that in civilized society today, at any rate in Great Britain, a fragile crust protects, and a tenuous curtain conceals, the private life of the individual in all walks of life and at all social levels, from the gaze and criticism of the public. The crust is thinner, the curtain less opaque, than in Victorian days; the line it cuts through the nation does not coincide, as it then practically did, with a line of social stratification that divided London “Society” from the country at large; but, in spite of the breakdown of class barriers and the penetrative assaults of radio, of television, and of the popular press, the curtain holds; and how resistant the crust can be when under stress was shown most strikingly in the weeks that immediately preceded the Abdication in 1936.

Some veil must be kept drawn to shield the privacy of the individual if a civilized life is to be possible in a society that is at once complex and libertarian. If those who “guilefully preserve” this veil may be thought to minister to a sort of hypocrisy, those who seek to tear it aside in the name of truth or morality are themselves often humbugs of a higher and a holier kind.

Suppose that a journalist or politician has obtained convincing evidence about the private morals of a prominent man which, if disclosed, would ruin his reputation and drive him, perhaps for ever, from public life. The guilty secret need not involve criminal liability; it is enough that it should be something that would cast serious scandal upon his name. Rumors, let us assume, are in circulation; this evidence would prove them true. What use should the possessor make of the damaging material?

Two conflicting answers are suggested: the first by those who insist that the issue in such a case is essentially a moral one—the school of thought represented by the newspapers already referred to (one of which declared that Parliament should “see exposed and cleansed whatever there may be in this noxious episode”), by the Bishop of Southwark, and by some at least of the pack that hounded Mr. Profumo from Ministerial office; the scandal, they insist, should not be covered up; the facts should be brought into the light of day; the claims of Truth are paramount.

Advertisement

The opposing school of thought maintains that in the interests of society at large, no less than those of the individual primarily concerned, the first duty of the possessor of such evidence (even if he is a politician or a journalist) is to keep it to himself; rather than lend his voice to the propagation of rumor, he should do all he properly can to preserve unbroken that façade on the maintenance of which depends the smooth functioning not only of the social organism but also, so long as ministries are manned by human beings and not by angels, of the machine of government itself.

Those who deplore the hushing-up of moral delinquencies on the part of politicians will insist that a nation cannot afford to be served by men whose private lives will not stand up to the severest scrutiny. On the other side it may be said that a nation looking for public servants cannot afford to limit to such persons the ambit of its choice. Certainly it would not conduce to the efficiency of administration if a blameless private life were deemed a necessary qualification for positions of public responsibility; such an ethical criterion would exclude from office many an outstandingly able man, and the impeccable morals of those who satisfied the test would hardly be a guarantee of their professional capabilities.

What is it, after all, that we really require of our public servants? Not, surely, that they should live spotless private lives (if they do, so much, from every point of view, the better), but that they should do their jobs efficiently and honestly, and should maintain in public the dignity and decency appropriate to their position. That a politician should be given to excessive drinking or that he should be a philanderer or an unfaithful husband is no doubt something that is for several reasons very much to be deplored; few people today, however, would feel that he should therefore on moral grounds be excluded, or extruded, from the Government. But if he cannot keep sober in public, if he is always to be seen about with women of obviously low character and habits, or if his private failing is displayed in newspaper headlines or made the subject of political debate, then he is surely disqualified from high office not on moral grounds but on grounds of decency; the rulers and representatives of a great nation must—the requirement is almost an aesthetic one—maintain in the eye of the public an appropriate dignity. Appearances count.

If that is so, it is in a real sense true to say that the crime in such cases consists in being found out; and that politicians or journalists who drag into the light of day the private weaknesses and peccadilloes of public men, so far from performing a meritorious action, are doing the nation a disservice by turning a private moral failing into a visible public blot; seeking to castigate one kind of offence, they are themselves accessories to the commission of another. Only over-riding considerations of public policy can justify in such a case the breaking of the protective crust erected by civilized society.

It was said, indeed, that such overriding considerations existed in the case now before us; it was not the moral aspect of the matter but its “security aspect,” if their professions are to be taken at face value, that moved those who pressed in Parliament for an inquiry into the Keeler affair—though this did not prevent Mr. Harold Wilson from sanctimoniously haranguing the House of Commons about the “odious record,” “the sickness of an unrepresentative section of our society,” and “the moral challenge with which the whole nation is faced.” Yet one wonders whether the public would ever have heard of the affair had not its circumstances, so heavily charged with possibility of scandal, afforded an opening for the Opposition to aim a crippling blow at the prestige of the Government, for dissident Conservatives to attempt the discomfiture of the Prime Minister, and for the proprietors and editors of newspapers to set before their readers a feast of nauseating innuendo. As soon as the matter was franked “Security” those who wished for one reason or another to exploit it could do so with a clear conscience, or at least with a plausible excuse, however little danger to security in truth existed.

Advertisement

What grounds were there in fact for supposing that a security leak had occurred? There was evidence that the Minister of War had had an affair with Miss Keeler at a time when she was on intimate terms (it is doubtful how far in fact the intimacy went) with an attaché at the Soviet embassy in London. But no one examining that evidence today is likely to conclude that she in fact ever obtained, or even asked for, any secret information from the Minister, let alone that she passed on any such information to a foreign agent. And, in any case, “Nobody in their right senses,” as Stephen Ward himself declared, “would have asked somebody like Christine Keeler to obtain any information of that sort from Mr. Profumo—he would have jumped out of his skin.” None the less, it may be said, there must have been a period of risk; and the real charge against the Government was that they did not detect and eliminate that risk through their Security Services. Was there not some fault in the organization of the functioning of the Services or in the handling by the Government of the information that reached it?

The answer is to be found in Lord Denning’s Report, which explains in detail how the Security Services are organized and how they operated in the present case; it traces, step by step, in fifty factual paragraphs, the whole complicated story; its vindication of the Services is complete. In 1961, says Lord Denning, they did not know of the Minister’s affair with Miss Keeler “and had no reason to suspect it,” and by the time the matter blew up in 1963 it had ceased to be a security risk. The bare fact of the Minister’s past association with her, whatever its political significance as a moral lapse on the part of a member of the Cabinet, was no longer a security interest, and in any case it was already known to the Prime Minister, and the suspect (as the Security Services were aware) was being directly confronted with the matter by his Government colleagues.

The critics, therefore, turned to a third line of attack; even if there was no actual, “leak,” and even if there was no real risk of one, the Government’s handling of the matter, it was said, was such that they had forfeited the confidence of the country and should resign forthwith. The wildest accusations were freely uttered: the Prime Minister was lying when he said he had not known of the affair; he had known the truth all along; if he had not known it, he ought to have; the Minister for War should have been “watched” (by the Security Services? by the police?) back in 1961; his colleagues should never have accepted—nay, they did not really believe—his denial of his guilt; at best, the story revealed a shocking record of apathy and carelessness, at worst, a conspiracy to shield “the Conservative establishment.”

Most of the cries raised at the time have now a hollow ring; no one really supposes that Mr. Macmillan was lying, or that the police should spend their time shadowing Cabinet Ministers at cocktail parties and at night clubs; such totalitarian procedures, even if they guaranteed (and would they?) perfect security, would involve a price too high for a free society to pay. One charge, however, still persists: the Ministers ought not to have believed Mr. Profumo’s protestations of his innocence. The charge is easy to make, but it is ill-considered. For even when all appearances are against a suspect, even when his colleagues feel in their bones that he must be guilty, still, if he backs up his repeated denials of his guilt by declaring his readiness to submit to cross-examination in the Courts and actually takes steps towards initiating a prosecution, what alternative have they but to accept his word—on which in this case he set his seal by offering solemnly to repeat his denial in the House of Commons? To accept it as more likely that a Minister in such circumstances should deceive his colleagues would be to acknowledge, and in a sense to be a party to, a debasement of the currency of public life.

Apart therefore from the moral issue, in which the Opposition officially disclaimed all interest, there was no solid substance in the case. What then were the motives of those who pressed so eagerly, in Parliament and in the press, for an inquiry? No doubt they were mixed, as motives usually are. No doubt they included an element of vindictiveness; the press were eager (as well they might have been) to avenge the searing exposure they had suffered at the hands of the Radcliffe Tribunal in the Vassall case (when two journalists who had published scandalous and fictitious stories about a Civil Servant had to be sent to prison for refusing to disclose their alleged “sources”) and the Opposition saw a heaven-sent opportunity of harassing the Government.

All the accounts before us agree that Mr. Wigg (a Labor M. P. who felt that he had suffered unjustly at Mr. Profumo’s hands not long before in an exchange about Kuwait) acted from the beginning as the whipper-in of the Opposition pack. He was in daily contact (says Lord Denning) with an enemy of Ward who at one point hired an agent who obtained the entré to Ward’s flat and enjoyed many intimate conversations with him. Yet, whatever personal or party feelings may have moved Opposition M.P.s, no doubt they genuinely believed the charges they launched so freely against their opponents. Mr. Wigg’s opinion of the Government may be gathered from a question that he asked when news of the tragic death and gruesome mutilation of two British soldiers in the Middle East had reached England and was awaiting confirmation: “Is it not a fact that Government circles did all they could to boost the story in the hope that it was true?” One who could believe that to be true of his political opponents could surely believe anything about them, and Mr. Wigg and his colleagues no doubt thought that they were acting in the public interest when they set in motion the train of events that led directly to the downfall of the Minister for War and indirectly to the death of Stephen Ward.

The Profumo affair engendered a mixed crop of “literature,” ranging from Lord Denning’s Report (surely the raciest and most readable Blue Book ever published), through ephemeral “revelations” of the kind that went to make up the cloudy atmosphere of the case.

Mr. Charlton’s brochure belongs frankly to the category of “revelations”; its author is a journalist who evidently gained Ward’s intimacy and enjoyed (like Mr. Lewis’s agent) a series of conversations with the osteopath in his flat. Mr. Charlton does his best—an experienced reporter’s best—to present an attractive portrait of his subject. But the impression that remains is that Ward, though certainly not mercenary where sex was concerned, was an unprepossessing individual, one of whose principal pleasures was to procure pretty girls and get them to undress in front of his friends.

Mr. Ludovic Kennedy’s main purpose is to prove that Ward’s conviction was the result of a miscarriage of justice. His book is an eye-witness account of the trial, giving the author’s impressions of the Judge, counsel, and witnesses, and his opinions on the procedure and the law applicable to the case. Mr. Kennedy spoils his account by his manner of presenting it, and weakens the effectiveness of his plea for Ward by his unremitting prejudice. As a reporter—apart from an idiosyncratic use of English: we meet “a mutual peer” (evidently a common friend of Mr. Kennedy and Ward) and six pages later “a tight concentric circle”—he is too bright, too knowing, too facetious; he cannot be content to report; Miss Keeler is a “nymph”; Dr. Ward is a “screaming hetero”; the jury are almost invariably “the rude mechanicals.” Sometimes this facetiousness seems to be due to spontaneous exhibitionism, the author simply cannot help showing off his whimsical humor; but more often it has a practical purpose: he is out to pour ridicule upon the prosecution or upon the whole proceedings. For Mr. Kennedy is, understandably, impatient of British judicial procedure—the absurd formalities, the archaic dress, the traditionally stilted language, the conventional and often outdated attitude on moral questions adopted by the law and some of those who administer it, and (in particular) the apparent irrationality of many of the rules of evidence: “Let no one pretend,” he writes, “that our system of justice is a search for truth. It is nothing of the kind. It is a contest between two sides played according to certain rules, and if the truth happens to emerge as the result of the contest, then that is pure windfall. But it is unlikely to.” There is an element of truth in this, but Mr. Kennedy spoils his case by allowing his feelings to get the better of his reason. Certainly the rules of evidence in British criminal proceedings are highly artificial, and there is a case, which many lawyers would support, for reforming them; elaborate regulations, at almost every trial, exclude a great deal of the truth. But these regulations have been developed in the interests of the prisoner, and the loosening up desired by Mr. Kennedy, if it meant more justice, would mean justice of a rougher kind; it would result in the conviction of many guilty men, and perhaps some innocent men, who under the present system would have been acquitted.

When it comes to the Denning inquiry Mr. Kennedy’s penchant for informality deserts him. Mr. Kennedy takes Lord Denning to task precisely because, in his admirably humane and common-sense report, he accepted evidence that bore the stamp of truth although it had not passed the rigid tests that would have precluded its admissibility in Court.

Ward was certainly the victim of a terrible misfortune, but it is hard to believe that he suffered an actual injustice. He might well have complained that he was tried at all, but not—in spite of all the play that Mr. Kennedy makes with conflicting evidence and anomalies of procedure—that the result of his trial was an unjust one. After all, he was acquitted on all but two of the charges he was tried on, and on those two charges—living on the earnings of Miss Keeler and Miss Rice Davies—the defense offered no evidence but the prisoner’s, which even Mr. Kennedy finds, on this issue, impossible to believe. Ward was obviously not above pocketing some of the earnings of his girls when he was hard up—after all, he himself provided for them generously—and in the circumstances of the case that was enough to justify a conviction.

But Ward was certainly not the kind of professional that the Sexual Offences Act was aimed at, the runner of a profitable call-girl racket; his object was not money, but sex for its own sake; the intimate glimpses given by Mr. Charlton leave no doubt of that. “Sex,” indeed, had so long and so deeply obsessed him that his palate had become jaded; hence the “vibro” the whippings, the nude parties, the “four-in-hands,” all of them well-attested variations that added a necessary spice to his every-day, or every-night, enjoyments.

But it was not for indulgences such as these that Ward was being tried, and the criminal element in his behavior, assuming it proved, was so trivial that one hopes that his sentence, if he had lived to receive it, would have been a light one—a possibility that adds a touch of irony to his suicide.

Why, then, was Ward put on his trial? Mr. Kennedy’s answer, and it is an answer very generally accepted, is that he was “a whipping-boy for the humiliations of the Government,” “the scape-goat of the Establishment”; that he suffered for the sins of the Society that he pandered to, the Society that deserted him in his hour of need.

That is an easy answer, and one very comforting to critics of “the Establishment,” but it does not quite make sense. For it presupposes a decision taken for political reasons and presumably at the highest level: the Cabinet (one is apparently asked to believe) decided to prosecute in order (to quote Mr. Kennedy) “to help restore the Government’s good name.” One can only say that if the Cabinet (or any other authoritative body) had the issue before it, and decided it on those grounds, they were guilty of a strange miscalculation; for it is hard to see how anybody’s face, least of all the Establishment’s, was to be saved by the washing in public of so much dirty linen, some of it marked with embroidered coronets. No: the true answer to the question appears from Lord Denning’s Report. The decision to investigate Ward’s activities was taken by the Commissioner of Police, and it was forced upon him by anonymous communications alleging that Ward was living on the immoral earnings of girls “and suggesting that he was being protected by his friends in high places.” The investigations so called for disclosed evidence which, to say the least, was (as events proved) adequate to secure a conviction. What would have been said of the authorities if in these circumstances they had failed to prosecute? Surely, that once more the Establishment had closed its ranks, that “Conservative circles” were shielding their protegé, and themselves, from the disclosures that would be bound to follow if he faced an indictment in open court. And who would have been the foremost to launch those charges? The very newspapers, the very politicians, who at the time were clamoring for an inquiry into the affair and now seek to saddle others with the blame for its results. If Ward was a victim of anything other than a concatenation of unfortunate coincidences, he was sacrificed not to the convenience of the Government but to the clamors of its critics, in Parliament and the press. His case is but one more example of the sacrifice of the private life of an individual in the supposed interests of the public; it was his peculiar misfortune that he forfeited not merely privacy but life itself.

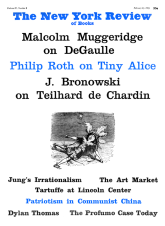

This Issue

February 25, 1965