If cookbook writing is somewhat less than inspired today, it had a more illustrious past. Or so, at least, Esther B. Aresty says in her book about cookbooks, The Delectable Past. An intense bibliophile, she has collected cookbooks for the past twenty years, and her impressive library, listed only partially in the appendix of her book, spans the centuries from antiquity to the present day.

Collecting often appears, to the non-collector, as a mild aberration to be viewed with amused tolerance. Too frequently the pursuit of rarity, particularly among book collectors, seems to be its sole justification. But Mrs. Aresty’s delight in the chase, and the excitement with which she flushes her quarry makes one almost believe in the virtues of cookbook collecting. Mrs. Aresty insists that collecting expensive rarities as such is not her goal and that cookbooks by influential nineteenth-century authors are still available at modest prices; she hopefully appends, however, that these are sure to be rarities some day.

Rare or not, the many early manuscripts from which Mrs. Aresty quotes have a vigor and charm lacking in the works of all but a handful of presentday writers. She offers a salad from a seventeenth-century English cookbook called The Whole Body of Cookery Dissected by Will Rabisha. The cook is directed to collect

all manner of Spring-Sallets, as buds of Cowslips, Violets, Strawberries, Primrose, Brookline, Watercresses, young Lettice, Spinage,…and what other things may be got…Then prepare your standard for the middle of your dish; it may be a wax tree or a castle made of paste, washed in the yolks of eggs and all made green with herbs and stuck with flowers, with about twelve supporters fastened in holes in your castle and bending out in the middle of your dish. Then having four rings of paste, one bigger than annother, place them so they rise like like so many steps. This done place your Sallet, a round of one sort on the uppermost ring and so round the others till you come to the dish; then place all your pickles from that to the brim and place the colors white against white and green against green…

Other quotations in The Delectable Past are freely translated from early Greek, Latin, Italian, and Old English. If Mrs. Aresty is responsible for them, one can only admire the skill and scholarship with which they were done. But it is to be regretted that the author chose to interrupt an engrossing survey with archly written recipes of her own devising, interspersed with cookbook clichés such as “appetizing,” “tasty,” “adds sparkle to any meal,” “for delighted cheers serve,” and “tasted as good as it looked.” Dishes such as Aspician Dilled Chicken and Aspician Ham and Figs from De Re Coquinara, 1 A.D., are hardly to be taken seriously when the chicken is made, as Mrs. Aresty suggests, with Worcestershire Sauce as a substitute for asafoetida and the ancient ham and fig dish with a canned or precooked ham and canned figs and fig juice. A recipe for a hash of capon from Forme of Cury, written in 1390, begins violently with the command to “take chickens and ram them together, serve them broken…” and emerges in Mrs. Aresty’s free adaptation as a chicken hash prepared with an ordinary cream sauce flavored with sherry and gratinéed with cheese. The result is little different from any dish you might get at Schrafft’s. As for the more fanciful and sometimes outrageous concoctions chosen at random from her collection (like Thin Cream Pancakes Call’d a Quire of Paper, a Taffety Tart, Balls of Italic, or Oeufs à l’Intrigue), their special appeal is dissipated when they are translated into contemporary cooking terms and prepared with tomato catsup, commercial sauces, packaged cream cheese, and the rest.

It is the recipes that have more or less survived the assaults of cooks upon them for centuries that would have been worth Mrs. Aresty’s culinary explorations. She has done this in her discussion of sauce duxelles, but in far too telescoped a fashion to be entirely satisfactory. Nonetheless, it is interesting to learn that the mushroom-shallot preparation, duxelles, indispensable to much of French classical cooking, was not devised by the Marquis d’Uxelles as is commonly supposed, but by his chef François Pierre de la Varenne. Author of Le Cuisinier François which first appeared in 1651, La Varenne, according to Mrs. Aresty, “seemingly at a stroke altered the cookery standards which had prevailed in France, and the rest of Europe as well, since medieval days.” Moreover, she points out, the notion that the French learned the art of cooking from the Florentine chefs of the two Medici Queens of France is not wholly true. La Varenne’s cuisine was lighter and more delicate than that of the Italians and much of his book laid the groundwork for French cooking as we know it today. Unfortunately, Mrs. Aresty insists again upon presenting her versions of nine of La Varenne’s recipes. Except for the sauce duxelles (originally called Champignons à l’Olivier) they are of only mild historical interest.

Advertisement

Most cookbooks published before the beginning of the eighteenth century were, like La Varenne’s Le Cuisinier François, written for use in the service of kings, princes, and noblemen. Mrs. Aresty quotes a dinner menu from a cookbook of 1570, The Cooking Secrets of Pope Pius V by Bartelemone Scappa, in which there are at least sixty courses served under the direction of four stewards and four carvers. The diners sat down to a table loaded with cold game birds, fish, salads, pastries, hams, melons, and baskets of fruit. The platters were handed around by one group of servants while others brought hot foods from the kitchen, and meanwhile, as Mrs. Aresty describes it, the carvers performed with dazzling precision at the credenza or sideboards.

Not until the eighteenth century was well under way were cookbooks directed at the bourgeoisie, or, according to an early writer, “homes of less consequence.” The first of these books appeared in 1739. M. Marin, its author, offered expert advice on how a member of the bourgeoisie could eat like a prince even if his kitchen staff consisted of a single cook. Interestingly enough, a cookbook published a few months ago says very much the same thing. The Vogue Book of Menus is as elevated in its attitudes as was Signor Scappa in his Secrets of Pope Pius V, but there are enough enticing nods towards the bourgeoisie to create the illusion that anyone can dine like the Duchesses of Windsor or Westminster, or, if one prefers, like the Astors, Lady Mendl, or Elsa Schiaparelli if Vogue menus are followed to the letter.

The authors may be right. The menus are brilliantly composed. There are buffet party menus for ten to three hundred people, menus for small dinners, formal dinners, holiday dinners; a section of luncheon, cocktail, and supper-party menus; and finally one unending succession of breakfast, luncheon, dinner, and supper menus for a weekend in the country with a Spartan hostess doing all the cooking for six guests who evidently do nothing from morning to night but eat.

If truffles, pâté de foie gras, and caviar are strewn about the book much too casually, there is also such sensible stuff as a good country pâté, a barley pilaff, an excellent braised tongue, to give the book a solid underpinning of honest cooking. And it is a pleasure to come upon so imaginative an adaptation of the Francillon Salad, that extravagant salade composée made famous by Dumas Fils in his play Francillon. Tatiana McKenna, Vogue’s food consultant, has wisely retained its original ingredients: mussels, potatoes, fresh herbs, and truffles, and kept to a minimum the wine, and sometimes champagne, which so many misguided cooks pour in with a heavy hand.

Sadly, a number of the other elaborate recipes in the book fare less well. The concept of encasing a cold filet of beef in an aspic made of two cups of bouillon and one cup of uncooked cognac is disconcerting to say the least. Even if the cognac were a fine champagne, the filet couldn’t possibly compete with the excessive amount of alcohol enveloping it. In a number of other recipes, the classic brown sauce, espagnole, is listed as an important ingredient; as these dishes are described, the sauce is indispensable to their success. Since no recipe is given for it, Vogue editors apparently assume that their readers will have an inexhaustible supply on hand. In fact, sauce espagnole is one of the most arduous and time-consuming preparations in French classical cooking and is seldom, if ever, used in the home, even in France. It is found most often in the kitchens of great restaurants where the ingredients for its preparation are always available.

But these are small matters in the face of The Vogue Book of Menus’ larger achievements. The menus, despite their special contexts, are sufficiently varied to be useful in any milieu, even “homes of less consequence.” Thanks to Tatiana McKenna’s sensible and tasteful approach, this is a valuable book.

The new Chamberlain Calendar of French Menus is a charming little book, which should help you recreate, if you can cook at all, that memorable French luncheon or dinner you may have had or yearned to have, in France. And to complete the illusion you need only look at the accompanying photographs by Samuel Chamberlain. Compiled by Narcisse, Narcissa, and Mr. Chamberlain, that extraordinary family responsible together and separately for the Flavor of France, the Calendars of Italian Cooking, and Bouquet de France, among others, this latest collective effort presents a comprehensive, if necessarily foreshortened, view of how the French entertain on a variety of social occasions. There are simple luncheon menus and Sunday dinners, menus in the grand style for holidays, each accompanied by obviously tested recipes for the more important dishes.

Advertisement

The châteaux of the Ue de France, sidewalk cafés, cathedrals, seashores, Provence, and finally Paris itself have been seen by Mr. Chamberlain’s selective camera as they might have appeared yesterday or a hundred years ago. No anachronisms disturb their purity. The menus have a similar quality. Except for cocktail hors d’oeuvres, a slightly dissonant concession to American tastes, every dish reflects the classic French cuisine. Perhaps it is because all the Chamberlains lived so much of their lives in France that their menus and recipes have that uncompromising simplicity typical of French family cooking at its best.

At the other end of the scale, Gourmet’s Menu Cookbook demonstrates quite decisively how not to plan a menu. Although the book is a large and handsome one and its anonymous authors get down to business without small talk, the menus with few exceptions are dull, dispirited constructions. In reading them it is difficult to dismiss the thought that most of the dishes were merely lifted from Gourmet Magazine’s vast recipe files and fashioned into menus at the typewriter without much thought or care. Who but a tired researcher with little cooking—or for that matter, eating—experience could have composed the following supper menus:

Calves Brains Fritters or Croquettes Anchovy Cauliflower Soufflé

Danish Rum Cream with Clear Raspberry Sauce

Mushroom Caps with Dilled Cheese

Brandade de Morue

Fennel Salad

Mocha Cream

or an informal dinner menu consisting of:

Scallops in Ramekins

Veal Scallops with Green Noodles

Strawberry Cream

The dishes in the first two menus are uniformly soft and creamy in texture and apart from the fennel salad in the second menu, monochromatic besides. The shellfish and veal scallops on the third menu are both cooked, according to the recipes that follow, with tomatoes. Moreover, all the menus, even the few good ones, are arranged in such a way as to place an intolerable burden upon any one but a professional or really skillful amateur cook. Except for the breakfast menus in which fruit juices and fruit appear comparatively unadorned, the individual dishes on many of the other menus are unnecessarily complex and reaching for effect. The results are frequently absurd: Sliced Tomatoes with Brandy and Olive Oil; Tomato and Orange Consommé; Sea Bass Baked with Mint; Tongue in Swiss Fondue; Orange Borsch, to name only a few.

Considered as a cookbook, Gourmet’s Menu Cookbook has nothing to recommend it. In fact, to cook from it is to court catastrophe. In many of the recipes, the cross references are positively bewildering and the inaccuracies and downright mistakes worse. The cook is told in one instance to broil a boned, marinated, flattened-out leg of lamb for ten minutes on each side and then to roast it in a moderate oven for two and one half hours until “the meat is tender but still pink inside.” Any cook should know that after two and one half hours (even omitting the broiling time) the lamb will not only not be pink inside but will be overcooked beyond recall.

In another recipe for lamb, this time a saddle, the cook is again told to roast the lamb (weight unspecified!) for only one hour or “until the meat is tender but still pink inside.” At the end of the hour the saddle of lamb (the one photographed on an adjoining page appears to be seven pounds or over) will certainly be pink at its outer edges but positively raw inside. Similar results will be achieved if you follow precisely the recipe for Filet of Beef en Croute. The filet is quickly browned in hot fat, allowed to cool, then spread with a layer of forcemeat and wrapped in pastry. The cook is now told to roast the filet in a 350 degree F. oven for 20 minutes, after which point it is to be removed from the oven and allowed to stand for 10 minutes more. Prepared, cooked, and served in this fashion, the Filet of Beef en Croute will be an expensive disaster. Because the forcemeat and the pastry around the beef will protect it from any significant penetration of heat (and that is their function in good cookery of this type), the filet will emerge from its 20 minute roasting period almost completely uncooked. And letting it stand for 10 minutes outside the oven will insure its being cold besides.

Sea food, vegetables, and sauces too, are cooked at your peril if you follow Gourmet’s Menu Cookbook to the bitter end. In a recipe for Scallops in Champagne (a dreadful idea to begin with), the directions for its preparation are technically so incorrect and chaotic that followed precisely, the scallops will emerge floating in a curdled, thin sauce of eggs, cream, and flat, hot champagne. Another recipe, this time for sautéed chicken, has the cook adding to the finished chicken “12 raw artichoke bottoms,” and is told to simmer them for 15 minutes before serving. During that time, needless to say, the still raw artichokes will have barely warmed through. Ironically, fifty pages later, in the vegetable section, the reader is cautioned to cook raw artichoke bottoms for 30 minutes (40 to 50 minutes would be correct) before they are ready to use.

The one redeeming feature of the book is the superb photography. Various dishes are reproduced in ravishing color, lovingly illuminated in every detail. It is of course unfortunate that many of the dishes photographed have little relation to the recipes accompanying them.

Were the Gourmet’s Menu Cookbook merely another publishing adventure in massive cookbook merchandising, it could be dismissed with a resigned shrug of the shoulders. But Gourmet Magazine and the two Gourmet cookbooks have had a long, impressive, and distinguished history. And their audience is a large one, toward which, it would seem, the editors of Gourmet have shown a singular lack of regard and responsibility.

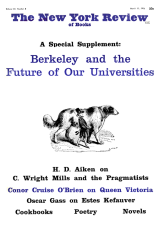

This Issue

March 11, 1965