London

A long battle behind the scenes is now under way in Bonn following last Sunday’s elections, when an unexciting campaign was followed by the anticlimactic victory of the Christian Democrats. The Social Democrats improved their position by 3 per cent—not sufficient to harass seriously Professor Erhard’s ruling party. They are disappointed; they had hoped for a much closer race and it now seems doubtful whether Brandt will lead them in yet another election campaign. The Social Democrats were criticized for pulling their punches in the campaign—for trying to appear respectable at almost any price, for not being radical enough. The Social Democrats undoubtedly tried to steal their rival’s clothes, figuratively speaking, but this was not the cause of their defeat.

If the election programs of the two main parties often seemed indistinguishable, this only reflects their growing similarity in social structure. The Social Democrats have substantial white collar support, the Christian Democrats considerable working class backing. The Social Democrats did worse than they expected, a failure that can be traced to the innate conservatism of the lower-middle-class voter, especially in South Germany and the Rhineland, and to the fact that their leader, though a very decent and sensible man, is not a magnetic personality. The poor showing of the Social Democrats will cause minor changes in party leadership. Even while excluded from participation in the national government, they will maintain their rule in about half a dozen of the Länder, such as Hesse and Hamburg. One of the pillars of the Hamburg local government, Helmuth Schmidt, is often mentioned as a possible successor to Brandt. He is younger and more dynamic, and certainly one of Germany’s best public speakers.

Professor Erhard, in the week after the elections, faces more serious problems, and at any rate more urgent ones, than the Social Democrats. If he will have a majority in the Bundestag, which is uncertain, it will be tiny and therefore unworkable. The Free Democrats who were his allies in the last coalition have proved on more than one occasion awkward partners, with their objections to Germany’s eastern policy, to the appointment of Franz Josef Strauss as a minister, and even to the relationship of Church and State. Erhard regards the Free Democrats as the only possible coalition partner, whereas his right-wing party colleagues—Adenauer and Strauss—prefer a great coalition with the Social Democrats. They reason that in coming years Germany will have to face a number of great domestic and foreign issues; and cooperation between the two major parties will be imperative. This coalition, unlikely at present, seems not impossible in the long run. Certainly it would be a prerequisite for the adoption of a more realistic policy on German unity and its Eastern borders. It is a question whether Erhard was more harassed in the recent campaign by political rivals or by friends in his own party—such as, for instance, former Chancellor Adenauer.

Adenauer, Strauss, and other Christian Democrats have been highly critical of Erhard and his foreign minister, Schroeder, whom they accused of lack of enterprise in foreign policy and undue pliancy vis à vis America and England. They favor a French orientation, though not necessarily sharing De Gaulle’s anti-American bias But De Gaulle is not an easy ally—they say in Bonn that whoever has De Gaulle for a friend doesn’t need any enemies—and his recent stand on Germany’s Eastern border was a serious embarrassment for his German friends. In the jockeying for position that is now going on in Bonn, Adenauer and Strauss will probably not succeed in unseating Erhard and replacing him with Gerstenmayer, the President of the Bundestag, as they had originally intended. For Erhard can regard the outcome of the elections as a personal triumph. Whether Strauss, who has been out of office since the famous Spiegel affair, will again be a Minister is an open question, and there is an even chance that Schroeder will continue as Foreign Minister. But any such changes or maneuvers do not mean that a major reorientation in German policy is in view. The pattern on the home front has been set for years to come: in foreign policy, an attempt will be made to asset German views more forcefully in the counsels of the West. But since the proposals of the German activists are nebulous—reunification and settlement of the Eastern border in a United Europe—and since Germany’s freedom of action is very limited, the new dynamic line if adopted will lead nowhere.

The German election campaign of 1965 will be analyzed by politicians and political scientists for months and even years to come. They will try to find out, for instance, why the Social Democrats made substantial gains in Nordrhein Westfalen while doing much less well in neighboring Lower Saxony. But these are the problems of the psephologists; for the rest is—more or less—business as usual in the big small town on the Rhine which became West Germany’s capital almost by mistake fifteen years ago.

Advertisement

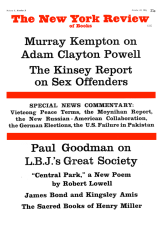

This Issue

October 14, 1965