Hongkong

The other day, just as India’s war began, the usual droves of pilgrims and tourists in Delhi removed their sandals in the hot sun to file along the walks of the great embanked unfinished Gandhi memorial, all the way to the marble cenotaph, or semi-cenotaph—some of his ashes really are there, some elsewhere. In the India of that day, his satyagraha, non-violence, already seemed altogether elsewhere.

One is taken to the memorial, as, in Bombay, one is taken to Mani Bhavan, Gandhi’s dwelling place and headquarters for seventeen years. One sees the thin white pallet of his fasts, the old-fashioned upright telephone, his spinning wheel, all in a clean corner of a little room, and his courtly letters informing the Bombay Chief of Police of his impending illegal acts. Thus, too, one is shown Nehru’s home and the site of his memorial. Later, one is told: “We are tired of vegetarian governments. We want a whiskey-drinking, meat-eating man.”

Those who say this are not government figures, or tycoons, or Sandhurst graduates. They are intellectuals. They may be editors of little magazines, directors of Institutes, poets, scholars of aesthetic theory. Themselves, they may be delicate, shy, abstemious, in the style of Indian intellectuals. On nearly any subject, they can express themselves in the withdrawn Indian subtlety we are likely to call other-worldly, or evasive. But not on the subject of Indian defense.

Kashmir, they say, can never belong to Pakistan. It may possibly become independent; but those who favor union with Pakistan had better be told forth-with they will be shot.

Today, the Unthinkable is a favorite subject of their thought. Strategic Studies are as respectable as Sanskrit, and military men can be, if not Pandhits, at least pundits, authors of articles and pamphlets. The Army, its system of conscription and reserves, its organization and equipment, all these are questions of the moment. How far do these patriotic concerns penetrate into this land of 461,000,000 people, sixteen major languages with hundreds of dialects, 1,261,597 square miles? Perhaps they are the only notions that have penetrated at all since Gandhi’s saintly politics.

These words are being filed while the only certain news from the borders is that men are killing one another there. When this is printed, India’s war with Pakistan, with China, may be stalled, it may be raging, it may already have ended in disaster. But whatever happens, it is hard to believe that the centuries of alluvial passivity and landslide slaughter have not reached some point to be marked. It is possible, of course, that millions of men in rags will squat on their heels by the roadside forever, starving, while between the sacked gorgeous palaces of the Moguls and the megalomaniac piles of the Empress Victoria the fields lie untended. Some men, it is true, squat and watch their water buffalo wallow, waiting patiently for the moment when they will squeeze some milk from these beasts which are as big as rhinos and have teats like a child’s glove. Others follow the white cattle through city streets, or pull rickshaws; keep shops, or edit papers. And the tycoons are erecting industrial plants and electrical signs. Banks open.

The visitor sees, four feet away but as if from a space-ship, the uncountable quantity of pain in small human limbs and faces, disposed on the earth in villages, in the dumps of Calcutta. He may think of Egypt, trying not to think of China. The fellahin suffer still, but the Aswan Dam is going up. Perhaps the energy of aggression is all we have to save ourselves with, and whether India is victorious, defeated, or honorably stalemated by U Thant, will not be what matters in the end. India is unique in our time for having produced a masterful saint, and why should one expect another from the same country?

We cannot forgive a country its saint, nor even forget. We think we love another people’s saint, and expect these other people to live up to his saintliness. Other people’s heroes, of course, we hate. But heroes are easier to find than saints, and what’s more, they love to expand their heroism from one human activity to the next, where it may even be needed. A hero might think eventually of such a thing as the growing of rice or the provision of clean drinking water. And, in our miserable human experience, there is nothing like a war to turn up a hero.

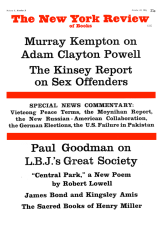

This Issue

October 14, 1965