The Vietnam debate reflects our intellectual unpreparedness. Crisis has arisen on the farthest frontier of public knowledge, and viewpoints diverge widely because we all lack background information. “Vietnam” was not even a label on our horizon twenty years ago. It was still “Annam” (the old Chinese term), buried within the French creation, “Indo-China.”

Our ignorance widens the spectrum of debate: Everyone seeks peace but some would get it by fighting more broadly, some by not fighting at all, and some by continuing a strictly limited war. Everyone wants negotiations. But to get them some would bomb North Vietnam and others would pause or stop.

Behind the cacophony of argument some hold the Europo-centric view that Vietnam is far away and in the Chinese realm, not in our realm. Others argue for a more global view that the balance of power and international order can be preserved only by containing the Chinese revolution as we are already doing in Korea and the Taiwan straits. Yet here the problem arises that it is not the Chinese whom we face in South Vietnam, but rather their model of revolution, Chairman Mao’s idea. And how does one stop a revolutionary idea?

How to deal with the Chinese revolution depends on how we understand it—specifically, what is the Chinese revolutionary influence in Vietnam? And behind that, what is the nature of the Chinese revolution itself? Can we ultimately deal with it in any way short of war? But where would war get us?

A long view is needed, an historical framework within which to see all the actors, including ourselves. (What are we doing so far from home?) Yet our knowledge of East Asian history is so meager it can mislead us. “History” is used as a grab-bag from which each advocate pulls out a “lesson” to “prove” his point. Some recall Manchuria in 1931: We failed to stop Japan’s aggression and it led on to Pearl Harbor. Others recall our drive to the Yalu in 1950: We ignored China’s vital interest in her frontier and got ourselves into a bigger war. Again, what was the “lesson” of Dien Bien Phu in 1954—were the French strategically overextended or merely tactically deficient in airpower?

“History never repeats itself” means that one can never find a perfect one-to-one correspondence between two situations. Each must be viewed within the long flow of events, not as an isolated “lesson.” Brief articles (like this one) can offer only limited wisdom. Nevertheless certain main outlines emerge from an historical survey. The Vietnamese and Chinese have had their own specific ways and interests, traditions and attitudes, and their own East Asian pattern of contact, not in the Western style.

The Traditional Model for Vietnam

China’s revolutionary influence on Vietnam comes from a long past. In the first place, Vietnam grew up as part of Chinese culture—the East Asian realm which included not only China in the center but also the peripheral states of Korea and Vietnam and Japan as well. All these countries took over the Chinese writing system in ancient times and with it the Chinese classical teachings, the bureaucratic system of government, and the family-based social order, so eloquently advocated in the Confucian classics. These countries have an ancient common bond in philosophy, government, and cultural values.

In Vietnam’s case, this Chinese heritage was imposed by a thousand years of Chinese rule in North Vietnam, the ancient homeland of the Vietnamese before they expanded southward into the Mekong delta. Independence from Chinese rule was gained by fighting in the tenth century A.D., but Vietnam then continued for another thousand years to be “independent” only within the Chinese realm and tribute system. Down to the 1880s, Vietnamese tribute missions, going over the long post route to Peking, acknowledged the superior size and power, the superior culture and wisdom, of the Chinese empire and its rulers. This filial or younger-brother relationship was broken only a few times when Chinese armies again invaded Hanoi (for example, in 1406 and 1789), only to be thrown out by the Vietnamese resistance, whereupon tributary relations were resumed. There were only these alternatives, to be ruled by China or to be “tributary,” in the Chinese cultural-political-psychological sense, taking China as a model. This went to the point of using the same structure of government and copying the Chinese law codes verbatim, with the same terminology, in Chinese characters, which were the official writing system.

Vietnam’s growth in the shadow of China was eventually balanced by the arrival of sea-invaders from the West. The early Portuguese adventurers and the later Dutch and British East India Companies landed their ships at Danang (Tourane), where our marines are today. This sea contact with the expanding West climaxed in the French takeover of the 1860s and ’70s. French colonialism during its eighty years brought both exploitation and modernization, in a mixture that is hotly debated and can hardly be unscrambled.

Advertisement

We Americans have thus had predecessors (even the Japanese in 1940-45) on the long thin coast of Vietnam. We are sleeping in the same bed the French slept in, even though we dream very different dreams.

Western sea power in Southeast Asia goes back 450 years. Europeans expanded westward into the empty Americas very slowly. They went east into populous Asia more quickly and easily. The resulting colonialism in Southeast Asia has now been superseded by the new relationships we are trying to work out in the name of national self-determination. We are on an old cultural frontier between the international trading world and Asia’s land-based empires. Vietnam, like Korea, has been caught in the middle and pulled in two.

Vietnamese patriots reacted against the French by learning modern nationalism from them. In so doing they continued to be influenced by the Chinese example to the north. The Chinese reformers of 1898 had their counterparts in Hanoi. Sun Yat-sen operated from there in 1907-08. When his Chinese Kuomintang reorganized itself on Soviet lines in the 1920s, a Vietnamese Kuomintang followed suit. In the same era, the Chinese Communist Party set a model for the growth of a Vietnamese Communist movement in the 1930s. The rise of Ho Chi-minh illustrates this trend. Both the French and Soviet Communist movements and Chiang Kaishek’s Whampoa Military Academy were in his background.

By the time the Chinese Communists came to power in 1949, they were in an even better position to give the Vietnamese the encouragement of example. Viet Minh patriots of the united front were trained to fight against the French in the sanctuary of South China. When the People’s Republic of North Vietnam eventually emerged in 1954 after the defeat of France, it was indebted to Chinese help but, most of all, to the Chinese Communist example.

Today in South Vietnam, the “people’s war of liberation” has developed from the Maoist model that took shape in China during the struggle against the Nationalists and the Japanese. Mao’s formula is to take power through a centralized Leninist party that claims to represent the people. This begins with establishing a territorial base or “liberated area,” inaccessible and defensible. From this base, the party organizers can recruit idealists and patriots in the villages and create an indoctrinated secret organization. Once under way, this organization can begin to use sabotage and terrorism to destroy the government’s position in the villages and mobilize the population for guerrilla warfare. Shooting down unpopular landlords or government administrators has a wide “demonstration effect.” When guerrilla warfare has reached a certain level, it can escalate to fielding regular armies, strangling the cities, and completing the takeover.

One appeal of this Maoist model is its do-it-yourself quality. The organizing procedure is carried out by local people with only a minimum influx of trained returnees and essential arms. The whole technique cannot be understood apart from the local revolutionary ardor that inspires the movement.

Historical Mainsprings of China’s Revolution

In China today we confront a revolution still at full tide, an effort to remake the society by remaking its people. Chairman Mao spreads a mystique that man can overcome any obstacle, that the human spirit can triumph over material situations. For fifteen years with unremitting intensity the people have been exhorted to have faith in the Chinese Communist Party and the ideas of Mao Tse-tung. With this has gone a doctrinaire righteousness that has beaten down all dissent and claimed with utmost self-confidence to know the “laws of history.”

Mao’s revolution puts great stress on the principle of struggle. The class struggle has made history. Each individual must struggle against his own bourgeois nature. China must struggle against Khrushchevian revisionism. The whole world must struggle against imperialism led by the United States.

Out of all this struggle among the 700 million Chinese has come a totalitarian state manipulated largely by suasion. Individuals work upon themselves in the process of thought reform, criticizing their own attitudes. Residential groups maintain surveillance on one another, as children do on their parents, as part of their national duty. Terror is kept in the background. Conformity through a manipulated “voluntarism” fills the foreground. No such enormous mass of people has ever been so organized. The spirit of the organization continues to be highly militant.

The sources of China’s revolutionary militancy are plain enough in Chinese history. The Chinese Communist regime is only the latest phase in a process of decline and fall followed by rebirth and reassertion of national power. China’s humiliation under the “unequal treaties” of the nineteenth century lasted for a hundred years. An empire that had traditionally been superior to all others in its world was not only humbled but threatened with extinction. Inevitably, China’s great tradition of unity, as the world’s greatest state in size and continuity, was reasserted. In this revival, many elements from the past have been given new life—the tradition of leadership by an elite who are guardians of a true teaching, the idea of China as a model for others to emulate.

Advertisement

Because the Chinese empire had kept its foreign relations in the guise of tribute down to the late nineteenth century, China has had little experience in dealing with equal allies or with a concert of equal powers and plural sovereignties. Chairman Mao could look up to Comrade Stalin. He could only look down on Comrade Khrushchev. An equal relationship has little precedent in Chinese experience.

Because China has been a separate and distinctive area of civilization, isolated in East Asia, the Chinese people today have a very different political heritage from the rest of the world. The most remarkable thing about China’s political history is the early maturity of the socio-political order. The ancient Chinese government became more sophisticated, at an earlier date, than any regime in the West. Principles and methods worked out before the time of Christ held the Chinese empire together down to the twentieth century. The fact that this imperial system eventually grew out of date in comparison with the modern West should not obscure its earlier maturity. As in her scientific discoveries and technology, China’s inventions in government put her well ahead of Europe by the time Marco Polo saw the Chinese scene in the thirteenth century. Perhaps this early Chinese advancement came from the continuity of the Chinese effort at government, carried on in the same area century after century, and dealing with the same problems until they were mastered. In contrast, Western civilization grew up with a broader base geographically and culturally, but this very diversity of origins and the geographical shift from the Mediterranean to western Europe may have delayed the maturing of Western institutions.

Thus the ancient Chinese had a chance to concentrate on the problem of social order, staying in the same place and working it out over the centuries. Their solution began with the observation that the order of nature is not egalitarian but hierarchic. Adults are stronger than children, husbands than wives. Age is wiser than youth. Men are not equally endowed: “Some labor with their minds and govern others; some labor with their muscles and are governed by others.” This common-sense, anti-egalitarian approach tried to fit everyone in his place in a graded pyramid of social roles.

At the top of everything was the Chinese ruler, whose virtuous example commanded the respect and obedience of all beholders. The Chinese monarchy institutionalized the idea of universal kingship atop the human pyramid. The emperor functioned as military leader, power holder and ethical preceptor at the apex of every social activity. An able emperor would recruit the best talent, use men in the right jobs, render the legal decisions, and even set the style of connoisseurship in art, while carrying out the sacrifices to heaven and superintending all aspects of official conduct. The monarchy became omnicompetent, not equalled by any other human institution.

Even before the Chinese unification of 221 B.C., ancient administrators had worked out the basic principles of bureaucratic government. They selected for their ability a professional group of paid officials who were given overall responsibility in fixed areas, instructed and supervised through official correspondence, and rotated in office. The Chinese empire thus very early embodied the essentials of bureaucracy which the Europeans arrived at only in modern times.

One of the great inventions of Chinese government was the examination system based on the contribution classics. It produced an indoctrinated elite who could either provide local leadership as holders of imperial degrees or else could be appointed to official posts and carry on administration anywhere at a distance from the capital. In either case, the products of the examination system, versed in the classical principles of government, were supporters of orthodoxy and authority on established lines.

Other innovations, like the censors who functioned as a separate supervisory echelon, added to the devices of Chinese “statecraft.” Chinese government also used the family system, confirming the special status of parents and elders over the young, and of men over women. The famous “three bonds” or “three net-ropes” (san-kang) tied together superiors and subordinates—parents over children, husbands over wives, and rulers over subjects. In effect, this was a doctrine of obedience, to be manifested through the virtues of filial piety, chastity, and loyalty, respectively. Within the family, the patriarch was like an emperor, while ordinary family members, each in his own status, depended on the group for their livelihood, their education and social life, and even for a religious focus through reverence for their ancestors.

As the Chinese socio-political order matured and grew, its influence radiated outward over the “Chinese culture area.” Because China was the center of civilization in East Asia, it served as the model for smaller states like Korea and Vietnam, whose rulers naturally became subordinate to the Chinese emperor. This hierarchic relationship was expressed in the tribute system already noted. But the rise of nomadic warriors like the Mongols on the grasslands of Inner Asia posed a new problem, for they were non-Chinese in culture and yet their military capacity enabled them to invade North China and eventually conquer the whole empire. The result was another Chinese political invention, under which it became possible for powerful non-Chinese peoples to participate in Chinese political life. This they did either as allies and subordinates of strong Chinese weakness, as the actual rulers of China itself. Thus the ancient Chinese empire again showed its political sophistication. Invaders who could not be defeated were admitted to the power structure. The Mongols in the thirteenth to nineteenth centuries could even seize the imperial power, but they had no alternative to ruling China in the old Chinese fashion.

When Westerners arrived on China’s borders in early modern times, they also began to participate in the Chinese power structure. They were generally given status as tributaries and until 1840 were kept under control on the frontier. Thereafter, under the so-called “unequal-treaty” system, the Westerners had to be allowed to participate in the government of China. This they did with special privileges in treaty ports protected by their gunboats and under their own consuls’ extraterritorial jurisdiction. In its beginning, this nineteenth-century treaty system followed Chinese tradition.

Eventually of course, Western contact brought in new ideas which undermined the old Chinese order. But not all the new ideas of modern times were wholly accepted. Christianity found only a limited following. Ideas of the sacred rights of the individual and the supremacy of law were not taken over. China picked and chose what it wanted to accept from the West. Scientific technology and nationalism were in time taken as foundations of economic and political change. But Western-style republicanism and the election process did not take hold. As a political device to take the place of dynastic rule, the Chinese eventually accepted Leninist party dictatorship. On this basis, the Kuomintang rose to power in the 1920s. Later the Communist success established the doctrines of Marxism-Leninism and techniques of Soviet totalitarianism and industrialization. The Sino-Soviet split now represents a triumph for hypernationalism geared to a revolutionary faith.

Cultural Differences and Conflicts

Even a brief sketch of the historical experience of the Chinese people indicates their cultural differences from the West. Some of these inherited differences have been selected and reinforced by the new totalitarian rulers. Chinese tradition is, of course, very broad. It affords examples of a Confucian type of individualism and defiance of state control. Some day these examples may be invoked for democratic purposes, but that time has not yet come.

Today we see these cultural differences affecting the status of the Chinese individual. The old idea of hierarchic order persists. “Enemies” of the new order, as defined by it, are classed as not belonging to “the people” and so are of lowest status. On the other hand, party members form a new elite, and one man is still at the top of the pyramid. The tradition of government supremacy and domination by the official class still keeps ordinary people in their place.

The law, for example, is still an administrative tool used in the interest of the State; it does not protect the individual. This reflects the commen-sense argument that the interest of the whole outweighs that of any part or person, and so the individual still has no established doctrine of rights to fall back upon. As in the old days, the letter of the law remains uncertain and its application arbitrary. The defense of the accused is not assured, the judiciary is not independent, confession is expected, and litigation frowned upon as a way of resolving conflicts. Compared with American society, the law plays a very minor role.

The differences between Chinese and American values and institutions stand out most sharply in the standards for personal conduct. The term for individualism in Chinese (ko-jen chu-i) is a modern phrase invented for a foreign idea, using characters that suggest each-for-himself, a chaotic selfishness rather than a high ideal. Individualism is thus held in as little esteem as it was under the Confucian order. The difference is that where young people were formerly dominated by their families, who for example arranged their marriages, now they have largely given up a primary loyalty to family and substituted a loyalty to the Party or “the people.” In both cases, the highest ideal is sacrifice for the collective good. Similarly, the modern term for freedom (tzu-yu) is a modern combination of characters suggesting a spontaneous or willful lack of discipline, very close to license and quite contrary to the Chinese ideal of disciplined cooperation.

The cultural gap is shown also by the Chinese attitude toward philanthropy. Giving things to others is of course highly valued where specific relations call for it, as when the individual contributes to the collective welfare of family, clan, or community. But the Christian virtue of philanthropy in the abstract, giving to others as a general duty, quite impersonally, runs into a different complex of ideas. Between individuals there should be reciprocity in a balanced relationship. To receive without giving in return puts one at a serious disadvantage: One is unable to hold up one’s side of the relationship and therefore loses self-respect. American philanthropy thus hurts Chinese pride. It has strings of conscience attached to it. The Communist spurning of foreign aid and touting of self-sufficiency fits the traditional sense of values. American aid does not.

Cultural differences emerge equally in the area of politics. In the Chinese tradition, government is by persons who command obedience by the example they set of right conduct. When in power, an emperor or a ruling party has a monopoly of leadership which is justified by its performance, particularly by the wisdom of its policies. No abstract distinction is made between the person in power and his policies. Dissent which attacks policies is felt to be an attack on the policy maker. On this basis, no “loyal opposition” is possible. The Western concept of disputing a power holder’s policies while remaining loyal to his institutional status is not intelligible to the Chinese. Critics are seen as enemies, for they discredit those in power and tear down the prestige by which their power is partially maintained. (This idea also crops up in Taiwan.)

Another difference emerges over the idea of self-determination. This commonplace of Western political thinking sanctions the demand of a definable group in a certain area, providing they can work it out, to achieve an independent state by common consent among themselves. This idea runs quite counter to the traditional idea of the Chinese realm that embraces all who are culturally Chinese within a single entity. Thus the rival Chinese regimes today are at one in regarding Taiwan as part of the mainland. Both want to control both areas. Similarly, they are agreed that Tibet is part of the Chinese realm without regard for self-determination. A supervised plebiscite would seem so humiliating that no Chinese regime would permit it.

Both the Chinese party dictatorships of modern times are also believers in elitism and opponents of the election process, except as a minor device for confirming local popular acquiescence in the regime. Elections on the mainland are manipulated by the Party. Taiwan has developed a genuine election process at the local level, but the old idea of party “tutelage” is far from dead at the top. Here again, a case can be made for the Chinese practice. Our point is merely its difference from that of the West.

Perhaps the most strikingly different political device is that of mutual responsibility, the arrangement whereby a designated group is held responsible in all its members for the conduct of each. This idea goes far back in Chinese history as a device for controlling populous villages. At first five-household groups and later ten-household groups were designated by the officials, ten such lower groups forming a unit at a higher level, with the process repeated until a thousand households formed a single group. In operation this system means that one member of a household is held accountable for the acts of all other members, one household for the acts of its neighbors, and so on up the line. This motivates mutual surveillance and reciprocal control, with neighbor spying on neighbor and children informing on parents. Communist China uses this ancient device today in its street committees and other groups. It directly denies the Western idea of judging a man by his intentions and condemning him only for his own acts.

Cultural differences lay the powder train for international conflict. China and America can see each other as “backward” and “evil,” deserving destruction. We need to objectify such differences, see our own values in perspective, and understand if not accept the values of others. Understanding an opponent’s values also helps us deal with him. The old Chinese saying is, “If you know yourself and know your enemy, in a hundred battles you will win a hundred times.”

All this applies to our present dilemma in Vietnam where our military helicopter technology is attempting to smash the Maoist model of “peoples’ war.” We face a dilemma: Appeasement may only encourage the militancy of our opponents, yet vigorous resistance may pose a challenge that increases their militancy. Fighting tends to escalate.

Manipulating Peking in a More-than-military Competition

One line of approach, quite aside from military effort, should seek to undermine the militancy of our opponents. Why not pay more attention to their motivation and try to manipulate it? Having seen how Mao Tse-tung has manipulated Khrushchev and Chiang Kai-shek has manipulated us, can we not do some manipulating ourselves? There are several elements to use. One is China’s enormous national pride, the feeling in Peking that this largest and oldest of countries naturally deserves a top position in the world. In the background lies the fact that China was indeed at the top of the known world for more than 3,000 years of its recorded history. The Chinese attitude of cultural superiority is deep-rooted and still plays a part in foreign contact.

A second element is the need of any Chinese regime for prestige. Peking rules an incredibly vast mass of people by means of an enormous and far-flung bureaucracy. The prestige of the leadership and the morale of the populace and bureaucracy are intertwined. The rulers must seek by all means to bolster their public image, show themselves successful, and make good their claims to wisdom and influence. For sixteen years Peking has buttressed its prestige by attacking “American imperialism,” but its need for prestige is more basic than any particular target of attack. Are there other ways to strengthen itself than by denouncing and “struggling against” the biggest overseas power?

Another element is the converse of the above—the accumulated fatigue of revolution. Chairman Mao’s exhortations to continued struggle and austerity betray his lively fear lest the new generation grow tired of “permanent revolution.” His eventual successors may respond differently to opportunities abroad. Finally, there are the concrete problems of the Chinese state, its need for foreign capital goods and food supplies, needs that may grow.

A program to take advantage of these elements, recognizing the realities of cultural difference, would seek to enlarge Peking’s international contact and work out a greater role and responsibility for China’s rulers in the world outside. Many express this in wishful terms—“If only China would join the international world.” Realists point out Peking’s reiterated refusal to do so on any feasible terms. What I am advocating here is not a single gesture but a continuing program, not an alternative to present policies but an addition to them. It is too simple to say that one cannot oppose an avowed enemy on one front while also making an accomodation with him on other fronts. On the contrary, this is what diplomacy is all about. The whole idea of manipulation is to use both pressure and persuasion, both toughness and reasonableness, stick and carrot, with an objective calculation of the opponent’s motives and needs. This is not foreign to President Johnson’s thinking.

On the issue of Communist China’s entry into the United Nations, one objection is that Peking in repeated declarations has set impossible terms. Peking demands that “America get out of Taiwan” and that the Nationalist Government leave the UN entirely if the Peking government enters any part of it. These are terms we cannot accept. They are thus tough bargaining positions. But we should never expect Peking’s entry into the UN to be achieved by a single cataclysmic act. It can only follow a long and tortuous negotiation, probably involving the whole organization. Negotiations of a sort are already under way.

The most practical objection to Peking in the United Nations is the trouble it will cause. The Communist capacity for impeding orderly procedures, obstructing and sabotaging collective effort, is well known. The prospect of getting mainland China into the international organization is not one to gladden the heart of any official who must deal with the resulting situation. No one should assume that our China problem will be easier. The argument for getting Peking in is simply one of choice between evils. The trouble it brings will be less grievous than the warfare that seems likely if Sino-American relations remain on their present track. We have learned to prefer small limited wars to big nuclear disasters. So we should try to substitute diplomatic wrangling and nasty competition with China all across the board in place of a prolonged military showdown.

In short, Peking’s presence in the UN is no panacea nor is it likely to seem to be a great improvement. It may at first seem like a disaster, and this has deterred every administration in Washington. But the presence of China in the UN offers a prospect of diversifying the struggle and diverting it from the military single track. Can we afford to let the Chinese revolution remain in its partly imposed, partly chosen isolation, hoping it will eventually lose its militancy?

One major stumbling block in this approach is Taiwan. There is no way for the United States to withdraw from Taiwan or cease to support its independence. Taiwan today is one of the larger and more prosperous members of the United Nations. We cannot turn our backs upon it, either morally or strategically. Indeed, any future Taipei regime that sought to join the mainland ought to meet our opposition for reasons of essential power politics.

But we can do much more to deal with the Chinese revolution than merely shoot at its protagonists to contain it militarily. The need for disarmament and for worldwide cooperation over population and food supply are only two of the forces pushing us toward a more active China policy.

What conclusion emerges from a survey of China’s revolutionary history and the cultural differences that separate us?

First, we are up against a dynamic opponent whose strident anti-Americanism will not soon die away. It comes from China’s long background of feeling superior to all outsiders and expecting a supreme position in the world, which we seem to thwart. Second, we have little alternative but to stand up to Peking’s grandiose demands. Yet a containment policy which is only military, and nothing more, can mousetrap us into war with China. Our present fighting to frustrate the Maoist model in Vietnam is a stopgap, not a long-term policy. We should add to this policy, and if possible substitute for it a more sophisticated diplomatic program to undermine China’s militancy by getting her more involved in formal international contact of all kinds and on every level.

The point of this is psychological: Peking is, to say the least, maladjusted, rebellious against the whole outer world, Russia as well as America. We are Peking’s principal enemy because we happen now to be the biggest outside power trying to foster world stability. But do we have to play Mao’s game? Must we carry the whole burden of resisting Peking’s pretensions? Why not let others in on the job?

A Communist China seated in the UN could no longer pose as a martyr excluded by “American imperialism.” She would have to deal with UN members on concrete issues, playing politics in addition to attempting subversion (which sometimes backfires). She would have to face the self-interest of other countries, and learn to act as a full member of international society for the first time in history. This is the only way for China to grow up and eventually accept restraints on her revolutionary ardor.

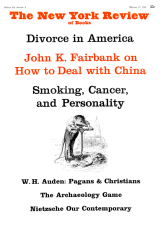

This Issue

February 17, 1966